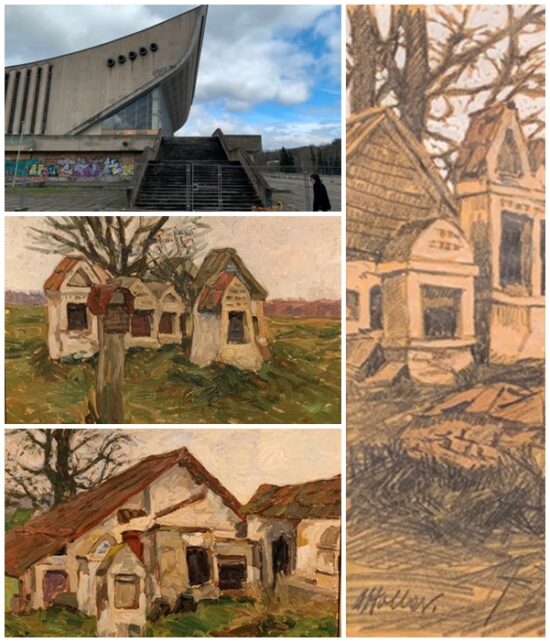

DOCUMENTS | OPINION | 2023-2024 “WORKING GROUP” ON VILNA CEMETERY | LIST OF MEMBERS | OLD VILNA JEWISH CEMETERY AT PIRAMÓNT | OPPOSITION TO CONVENTION CENTER | CONFERENCE OF EUROPEAN RABBIS (CER) | THE “CPJCE” LONDON GRAVE TRADERS | CEMETERIES & MASS GRAVES | LITHUANIAN JEWISH COMMUNITY AFFAIRS | HUMAN RIGHTS

◊

◊

Excerpts from Rabbi Elchonon Baron’s video:

“The use of any Jewish cemetery, for anything except the cemetery, is strictly forbidden in Jewish law and tradition. Most senior rabbis are very perplexed at the recent indication here in Vilna that perhaps there is an attempt to make a museum on the Shnípishok Cemetery, where our giants are buried. And they are claiming that this is in the name of senior rabbis. I mentioned to Rabbi Sariel Rosenberg [head of the Bnei Brak Beth Din] a few weeks ago that people are saying in his name that we can make a museum on the cemetery. We asked him exactly what it is possible to do. And he said: Nothing else — except matséyves [gravestones].

“There will not be a museum on Shnípishok Cemetery! There will not be a convention center! Woe is to anyone who tries. Because the Jewish souls want to rest in peace. Nothing will succeed there. There’s nothing to talk about. We won’t let it, it won’t happen!