Opinion | Books | Dr. Bubnys & Official State Holocaust Research in Lithuania | Red-Brown Commission | Genocide Center | Politics of Memory | Lithuania | History

◊

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

◊

Prolific historian, director of the state’s Genocide Center, and far-right activist. On 23 June 2020, Dr. Arūnas Bubnys addressed an ultranationalist rally celebrating the 79th anniversary of Hitler’s invasion (and onset of the Lithuanian Holocaust), flanked by large posters of Jonas Noreika and Kazys Škirpa, two major collaborators in various phases of the genocide of Lithuanian Jewry (96.4% were killed). In his speech he taunted the (silent) DH observers on hand. See reports here and here, and DH’s section on Dr. Bubnys’s work and positions over the years.

◊

Arūnas Bubnys’s book The Holocaust in the Lithuanian Provinces (Holokaustas Lietuvos provincijoje, Margi raštai, Vilnius, 2021) is another publication of the International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania (ICECNSORL). Up until now, books published by the Commission were academically written and appreciated by a sophisticated readership. Moreover, they were always published in both Lithuanian and English. This book is different. It is available only in Lithuanian. Previously published monographs would also include Commission-approved conclusions; this book has no such thing. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the Commission’s academics did not discuss the book among themselves before its publication. But let’s start at the beginning.

raštai, Vilnius, 2021) is another publication of the International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania (ICECNSORL). Up until now, books published by the Commission were academically written and appreciated by a sophisticated readership. Moreover, they were always published in both Lithuanian and English. This book is different. It is available only in Lithuanian. Previously published monographs would also include Commission-approved conclusions; this book has no such thing. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the Commission’s academics did not discuss the book among themselves before its publication. But let’s start at the beginning.

The book is geographically quite extensive: 23 counties and 140 towns are cited. This is really a lot, but it is also quite obvious that the coverage of towns in different counties is unequal. When it comes to Šilutė county in western Lithuania, for example, several camps and fates of individual Jews are mentioned in passing, but no single town is described. For the Marijampolė county, only the fate of the Jews of Marijampolė itself is presented. Šiauliai xounty (15 towns) and Alytus County (12 towns) are the most extensively covered.

Of course, Bubnys put a lot of labor into this book: this is one of the most comprehensive treatments of the topic to this day. Geographically, The Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania offers a broader coverage, as it mentions all massacre sites in the country. However, by focusing on massacre sites rather than towns of residence of the victims, it the Atlas occasionally begs the question of happened to Jewish communities of a particular town or towns?

But Bubnys’s book lacks an explanation of why everything is so fragmented. One of the possible explanations can be found in the chapter on the Šiauliai county where, speaking of himself the author reports:

Out of 22 Jewish communities that existed in Šiauliai county (not including the city of Šiauliai per se) before the war, the author describes only the destruction of those 15 communities on which he managed to collect at least a minimum of information. (p. 382)

Bubnys does not disclose his criteria for this minimalization of information. Thus, we are given the explanation that almost a third of the communities (seven) that existed in Šiauliai county before the war simply “disappeared without a trace.” I would think that they deserve at least to be named. Otherwise, what does the solemn slogan “We remember” ― next to which every year the good people of Lithuania and the world at large have their photos taken ― really mean? Around 140 towns comprise but a bit less than a third of all Jewish communities in Lithuania. Why so few? Does the author know nothing about the fate of the rest? I find that odd, since, say, in Prienai or Želva, one can find mass graves and at least some information on what happened there. Perhaps the scope of such work was too big for one author and he simply did not manage to cover it all. But then that should be duly ― and clearly ― noted in the monograph.

Then there are controversies among historians. The book avoids not only discussing controversies but even mentioning their existence. This, again, adversely affects the scholarly probity of this research. This may also be why no information on certain towns is provided. Bubnys uses criminal cases of people convicted during the Soviet years as his source. Some of these people were later rehabilitated by the Supreme Court of Lithuania, which issued rehabilitation certificates but never provided any arguments on why they had been rehabilitated. Therefore, it is problematic to use the evidence from such cases as historical sources, and this is nowhere discussed in the book. One can only wonder whether Bubnys really did not have any data on the destruction of some communities, or perhaps he made a conscious choice not to write about them due to possible legal conflicts.

Let us take Kazlų Rūda as an example: there are no historical works on the Jewish community of this town; this may have something to do with the fact that one of the persons, convicted by the Soviets for his activities during the War, was rehabilitated by the Lithuanian state after the collapse of the USSR. The Supreme Court’s verdict voided the evidence collected by Soviet prosecutors, and Lithuanian law enforcement did not manage to replace it. Did Kazlų Rūda’s Jewish community disappear into thin air? The question is not only a legal one, whether a certain officer of the time was guilty or not. The question is: what happened to the town’s Jews? Is the fate of this entire town of Jewish citizens of Lithuania to be relegated to the unmentionable?

A positive quality of the book is its sources. Besides the usual documents and historical research papers found in the Lithuanian Special Archives (LSA), the Lithuanian Central State Archives (LCSA), and the Wroblewski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, Bubnys also uses memories of Jewish survivors collected by ethnographers, as well as data on the Jewishgen.org website. This seems like a step towards bridging the gap between the historians’ and the survivors’ narratives. However, when various controversies are not discussed and on occasion specifically avoided, this step also seems quite timid. In this sense, Aleksandras Vitkus’ and Chaimas Bargmanas’ book The Holocaust in Samogitia (Holokaustas Žemaitijoje, Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras, 2016), often quoted by Bubnys, is much more advanced. Although, to be fair, at least once, Bubnys himself discusses the discrepancies between his own writings and Jewish memories:

In Lithuania, the Nazis tried to implement discrimination of Jews by using local inhabitants as a proxy. The German officers themselves, who would give orders to guard and control Jews, would stay in the shadows. For, during their forced labor, which would mostly be senseless (e. g., carrying stones from one spot to another, and then the next day carrying them back), Jews would mostly communicate with local men. Among these local guards, some individuals would appear to take pleasure in demonstrating their hatred towards Jews. E. g., Ch. Černiavskis was forced to wear and kiss the Soviet five-pointed star that was taken off the roof of a local millhouse. Therefore, many Jews would think that their true oppressors are Lithuanian, not German. (p. 551)

The author’s attitude here is very simply disappointing and rapidly fades into the usual apologetics and shirking of moral responsibility by nationalistic scholars. But Bubnys is not the first. Indeed, such statements are repeated from S. Buchaveckas’s article about Pilviškės published in 2011.

The author claims that “the number of selected counties is sufficient to imply a model of the Holocaust in Lithuania and to come to adequate conclusions that would apply not only to the selected counties, but to the provinces as a whole.” We do note that Dr. Bubnys is one of the most productive Lithuanian historians writing about the Holocaust, and that this work is an important step in research on Lithuanian history. The book gains additional significance when, in the introduction, the author promises to “analyze the events of the early stages of the Nazi-Soviet war, as well as the Lithuanian rebels’ (partisans’) rallying in the provinces, their attitudes and actions towards Soviet officials and Jews, and the main moments of the persecution of Jews.” He also promises to reveal, as much as it is possible, the number of people involved in the massacres (i. e. Jew killers), as well as their “organizational allegiance (German gestapo officers, police officers, white-ribbon wearers, soldiers of the self-defense units, etc.)”. We also know that he headed a research unit that compiled a long list of Holocaust perpetrators.

However, in this sense, the book disappointed me. It is a far cry from the researchers that he led could have disclosed, in the actual environment of today’s Lithuanian institutions and historians, with their list of the Holocaust perpetrators. The perpetrators here are mentioned in an even more fragmented way than the destroyed communities, on which, as mentioned earlier, no data is provided.

In some sections, attention to various partisans actually even overshadows the Holocaust. For example, in the section on the town of Juodupė, which takes up three pages, there is some interesting information on the town’s white-armbander unit. However, nothing is included about the cruel persecution suffered by Juodupė’s Jews, or about the fate of this community. While reading the section, I found myself wondering if the book was really on the Holocaust… However, it must have been only the section on Juodupė in which the author has lost sight of his own stated primary goal to such an extent.

Bubnys’ attitude to some issues must be criticized. I will now discuss such passages. Already in the introduction, following Liudas Truska, the author distinguishes two currents in the Lithuanian historiography of the Holocaust:

The traditionalist and the critical. Those in the former try to diminish the extent to which Lithuanians took part in the Holocaust, to partly justify their compatriots’ actions, and to alleviate their guilt. This current essentially continues the conservative historiographical and political line of the Lithuanian diaspora. Representatives of the latter currently try to analyze the Jewish genocide in Lithuania objectively and critically, without concealing their compatriots’ crimes. Telling the truth about the Holocaust is an extremely painful and difficult process in Lithuanian society. (p. 16)

I see no secret here: diminishing the extent of the Holocaust, justifying its perpetrators or alleviating their guilt has a name — Holocaust denial and distortion of history. As long as we consider works of this kind to be “history” it will always be difficult to tell the truth.

The book’s chronology of events raises some questions, too.

Contrary to Western European countries, Lithuania first experienced the Soviet occupation and only then the German occupation. Injustice experienced during the Soviet occupation turned a big part of the Lithuanian society into supporters of the Germans and enemies of the Soviets and Jews (p. 18)

I would like to ask: really? What was the annexation of the Klaipėda (Memel) Region then? One must notice that this emphasis of the Soviet occupation “coming first” is an important postulate of the current wave of Holocaust denial that Bubnys calls “traditional historiography,” a justification for collaboration with the Nazis. Noticeably, the real, and not alleged, precedence of the Nazi occupation is never used by authors of this current wave to justify Lithuanians’ collaboration with the Soviets. It is hard to understand the thought process of someone who claims that in Lithuania, contrary to Western Europe, March 1939 came later than June 1940.

The absurdity of the phrase in question is only underlined by a chapter at the end of the book, “The Šilutė (Heidelkrug) County.” A very brief description of the 1939 events is included here:

When, in March 1939, the Klaipėda Region (including the Šilutė County) was incorporated into Nazi Germany, local Nazis destroyed a synagogue in Šilutė and ravaged the Jewish cemetery. Those few Jews who remained in Šilutė suffered persecution by Nazi government institutions. (p. 575)

Does Bubnys really think that in Lithuania, as opposed to the rest of Europe, the year 1939 came after 1940 and 1941? I do not think so, I think he simply decided to stay silent about those ten to twenty thousand (according to other sources, a bit more than ten thousand) Jewish and Lithuanian refugees who escaped the Nazi-taken Klaipėda Region. Those who fled the Nazi occupation in the year 1939.

The book contains quite a few stereotypes, also used by Holocaust deniers. I will mention several of them. For example, this description of events:

In the first weeks of the Nazi occupation, the persecution of remaining Communists, Young Communists, and Soviet activists of various ethnicities started. The first Jewish victim in Merkinė was Giršas Gužanskis. Allegedly, local inhabitants beat him to death with shovels on the town’s central Kauno Street. On June 24 [1941], the white-armbanders arrested a group of Jews, drove them to a cemetery, and ordered them to dig a hole. Among those arrested were Robertas Arolianskis, Šlomas Goldmanas, Dovydas Vildkinas, Šmuelis Dovas Pugackis, Icchakas Kopelmanas, Dovas Kravicas, and Menachemas Krikštanskis. After they dug the hole, the men were shot and buried. (p. 55-56)

As we can see, a story that depicts a massacre of Jews starts with a stereotype. This is an attempt to relate ― and/or equate ― Jews with Communists. Or take these two passages:

In the first weeks of the occupation, up until around August 1941, Jews in Kaunas county would be persecuted mostly not out of racial and ethnic hatred (not because they simply were Jewish), but for political reasons, as collaborators and supporters of the former Soviet occupation regime. (p. 101)

However, already on the next page, the author refutes his own claim:

The first larger massacre in Kaunas County, according to a report by the head of the German Security Police and the SD III Operation Battalion K. Jager [the Battalion took over the Security Police functions in Lithuania on July 2, 1941 —E. B.], was carried out on July 9, 1941, in Vandžiogala. There, 32 Jewish men, 1 Jewish woman, 1 Lithuanian woman, 2 Lithuanian Communist men, and 1 Russian Communist man were shot. (p. 102)

In the book, Bubnys mentions at least several cases in which Jews in Kaunas County had been persecuted even before the Nazis showed up:

The Petrašiūnai rebels shot 10 and captured 30 Red Army soldiers, captured around 50 carts of escaping Jews and transferred them to the Kaunas Commandant’s Office. (p. 107)

When the War broke out, many Jews from Kaunas and Jonava tried to flee. Fleeing Jews and Soviet activists were bombarded by German planes and shot at by anti-Soviet Lithuanian partisans. (p. 108)

[In Rumšiškės,] already on June 26, the partisans started arresting former Communists, Soviet supporters, and Jews who had favored the Soviet government. The battalion’s soldiers would also arrest small groups of Red Army soldiers and Jews fleeing from Kaunas towards Vilnius […] The arrested Jews would often be robbed by the partisans. (p. 120)

There are facts that attest to the persecution and killing of the Kaunas county Jews ― because they were Jews ― already in June. In Kruonis, the persecution and bullying of Jews started on June 29. Jews were forced to pay indemnities, and eight thousand rubles were collected this way. On the night of June 29-30, two Jewish families were shot. (p. 118)

So, there we have it. Why is Bubnys trying to feed us the counterfactual claim: “Jews would be persecuted mostly not out of racial and ethnic hatred (not because they simply were Jewish)”? And what does this “mostly” mean, if the book only describes events in less than a half of all towns, and even when it does, no data of the events at the beginning of the war can simply be found? Why is the data from Petrašiūnai, Jonava, and Rumšiškės, where Jews were persecuted, brutalized, murdered, before the arrival of the Germans, neglected, as well as from Kruonis, where persecutions started already at the end of June? The author does not provide any data or arguments on why the persecution of Jews was allegedly limited to “political reasons.” This is a major feature of some current incarnations of Holocaust downgrade, mitigation, and obfuscation.

We find attempts to diminish the significance and scope of the events, for a murder of even one person is already an act of terrorism against the whole community. Let’s take Kėdainiai:

Murders of individual Jews would also take place. The white-armbanders beat to death former cinema owner M. Bergeris and shot to death Rubinas Chesleris. (p. 133)

Or Rokiškis:

As the Wehrmacht was marching into town, Jakobas Jakobsonas, who was observing the German soldiers through a window, was shot. He was the first Jew to be murdered in Rokiškis. On the same day, Katrielis Šemetas was shot to death while returning from Jakobsonas’ funeral. (p. 351)

Bubnys particularly revels in frequently entangling massacres of Jews with the persecution of Soviet activists:

The first Jews murdered in Veliuona were shot in the town’s Jewish cemetery in early July, on the orders of the head of a “partisan” battalion J. Milius. Three Jews were shot to death, the fourth one managed to escape (he was not local, but from Jurbarkas). These Jews were shot to death as Soviet activists. (p. 123)

I have yet to hear of some differential proceedings when shooting “Soviet activists” and “Jews.” Such alleged differences are not discussed by Bubnys. Furthermore, I have doubts about the presupposed “Soviet activism” of the non-local Jew. Could he have simply been a Jew fleeing war and mayhem?

Or Ariogala:

In mid-July, the white-armbanders arrested 14 more Communists and Soviet activists, most of whom were Jewish.

Here, Bubnys mentions some surnames, one of which is quite interesting: two Šerienės, a mother- and daughter-in-law. One must agree that mother- and daughter-in-law are some interesting “offices” which are nowhere to be found in the Bolshevik employment structure… Bubnys does not bother to explain this.

Or Rokiškis:

In the first weeks of the Nazi occupation (from June 27, 1941, to August 14), former Soviet officers, Communists, and Young Communists of various ethnicities would be arrested and shot. The first major arrest of Rokiškis Jews was carried out already on June 29. Arrested Soviet activists and Jews were driven to the Stepononiai forest (about five kilometers north of Rokiškis) in small groups and shot there. Around July 8, white-armbanders (former partisans) selected 108 young Jews aged 14 to 30 and told them that they would be brought to Biržai for work. On the same day, all arrested youths were driven to the Stepononiai forest and shot to death that night. On July 22, 1941, soldiers of the self-defense unit shot to death around 30 Soviet activists in the Stepononiai forest. (p. 351-352)

I would like to direct the reader’s attention to the chronology mentioned in this passage, “the first weeks of the Nazi occupation (from June 27, 1941, to August 14)”. It will be important when we come to discuss Bubnys’s conclusions.

During and after the uprising, Skapiškis’ police officers, rebels, and the auxiliary police would arrest individuals who had collaborated with the Soviet occupation regime. According to some data, the battalion arrested more than 100 Jews, around 50 Lithuanian Soviet activists, and around 30 soldiers of the Red Army. (p. 365)

Was Jewish ethnicity legitimate evidence of collaborating with the Soviets?

Or Linkuva:

After the German occupation of Lithuania, on June 28, 1941, the battalion of J. Jakubaitis and J. Tinteris arrived in the town of Linkuva. Arrests of Soviet activists and Communists would become even more frequent, the jail of Linkuva (former grain warehouse) would see new inmates every day. They were being interrogated, beaten, and then either shot or released. These were people of various ethnicities (mostly Lithuanians and Jews). In 1944, a commission that investigated fascist crime found that, at the beginning of the Nazi occupation, 71 Soviet activists and Communists were murdered in Linkuva (37 bodies were identified, 34 were not). (p. 387)

This is a very interesting case. Could Jews, suspected of Soviet sympathies, be not only shot after the interrogation, but sometimes released? Perhaps it is a rare curious case (then I would like to see some names of the “released Jews” if even one existed), but, most probably, it is all part of a grand distortion of the Holocaust history. Sadly, it is not the only such case in the book.

Partisans attacked a train with Red Army soldiers and Soviet activists at the Saldutiškis railway station. (p. 426)

Bubnys could be more careful with his historical interpretations. I do not know of any sources that would claim that, after war broke out, only Red Army soldiers and Soviet activists would be allowed to board trains. Most probably, this is an account of an attack, carried out before the arrival of the Germans, on a train that carried refugees. Bubnys’s source here is the Nazi magazine Karys (The Soldier), issue for July 18, 1942. Seems like a case of a piece of 1942 Nazi propaganda being uncritically transferred to a twenty-first century history book.

Or Rietavas:

In the first days of the Nazi occupation, the white-armbanders would arrest Communists and Soviet activists of various ethnicities. Among those shot to death, 4 were of Jewish ethnicity. (p. 473)

This description does not include the Rietavas rabbi, Rabbi Fondileris and mashgiach (supervisor of ritual kosherness law) Rabinovičius. Were they among the “Communists and Soviet activists of various ethnicities?” Criminal case No. LYA K-1 58 9067/3 (found in LSA) does not support Bubnys’ version, either. It simply provides data that the Jews in question were simply hiding, the Lithuanian white-armbanders would go on hunting them on several occasions, until they finally caught and murdered them.

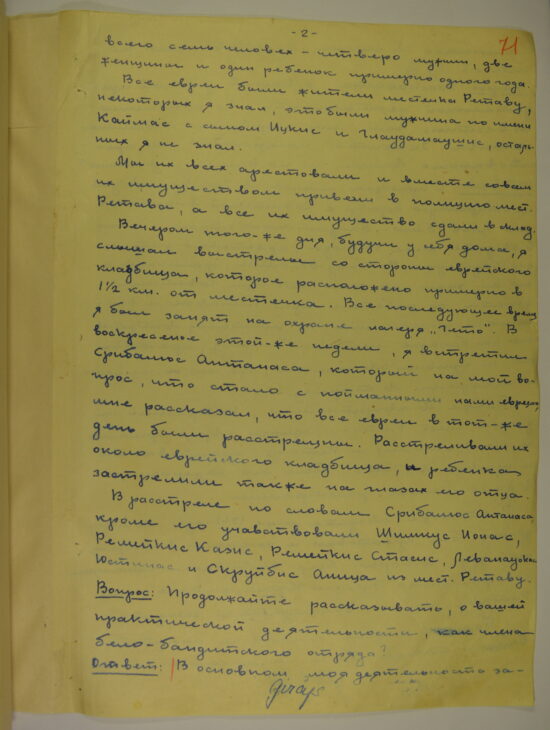

From case no. LYA K-1, 9067/3 pp. 70-71 re murder of seven Jews in Rietavas. Bubnys cites the victims here (p. 71) as “Communists” (they were: four men, two women and one child)

And then:

In the first weeks of the Nazi occupation, former Communists, Young Communists, Soviet officers, and supporters of various ethnicities would be arrested. The persecution was so massive and active that the government even had to dampen the enthusiasm of the “partisans” on their warpath. (p. 509-510)

On July 10, the governor of the Ukmergė County released an order to avoid senseless shootings of Lithuanians (p. 510).

Bubnys manages not to notice that the governor said nothing on the Jewish issue, nothing to protect citizens of Lithuania of whatever ethnicity. On July 10, 100 Jews were taken from jail and massacred. This is also in Bubnys’ book. How did that happen: persons of “various ethnicities” were arrested, but Jews were murdered? Happenstance?

Sometimes, Bubnys “develops a taste” for summaries; writing about the town of Musninkai, he summarizes the events in such fashion:

After the Nazis occupied Lithuania, persecution and discrimination of Jews began. In the first weeks of the occupation, mostly Jews that had been involved in Communist and pro-Soviet activities in 1940-1941 would be persecuted: Communists, Young Communists, employees of Soviet institutions, and active Soviet supporters. They were deprived of their citizens’ rights and had to wear special badges (Stars of David, etc.). Later, Jewish ghettoes and temporary isolation camps would be established. Mass arrests and massacres of Jews in Lithuania started in mid-August, 1941. All persons of Jewish ethnicity would be arrested and murdered, regardless of their political convictions and activities, gender and age. Lithuanian government apparatus, subordinate to the Nazi rule, was involved in the process of persecuting and massacring Jews: county governors, district elders, and various police forces (public police, security police, police battalions and companies, battalions of the auxiliary police (the white-armbanders). The Jewish genocide (the Holocaust) was carried out at once in all counties and districts of Lithuania where Jews lived. (p. 315)

This is one of the worst cases of historical misinformation in the book, trying to imply that in the earlier “Lithuanian phase” it was principally Jewish Communists who were targeted, and only in the later “German phase with Lithuanian collaboration” that the focus turned to “all Jews.” Bubnys does not provide data to prove that, either, that Jews would somewhere be ordered to wear Stars of David only if they had collaborated with the Soviets. This is a whole new phase in the distortion, obfuscation and (from the point of Lithuania) denial of Holocaust history.

◊

The book contains chilling inaccuracies. In reference to events in the town of Vainutas, Bubnys quotes a document by the Vainutas police chief which declares that able-bodied Jews had been transported to Germany for agricultural labor and those who could not work or wereill had been transported to Germany and admitted to a hospital (p. 451). The document is taken from Mass Murders in Lithuania (Masinės žudynės Lietuvoje, vol. 2, p. 280). Bubnys does not provide any additional comment, although it is obvious that the ill Jews were not admitted to the hospital, they were simply murdered. By the way, this fact is also mentioned in The Holocaust in Samogitia by Vitkus and Bargmanas (p. 351), which Bubnys cites more than once. Another source cited by Bubnys, The Holocaust Atlas of Lithuania, also mentions that a portion of the Jews transported for labor could also have been murdered. The story of Vainutas’ Jews, as written by Bubnys, can be classified as a mistake brought on by uncritical reading of Nazi documents.

Even more questions arise after reading Bubnys’ conclusions on the Holocaust in Lithuania. The most dubious is the first:

Late June – mid-July, 1941. Motives of political persecution were dominant during this period. Jews would mostly be arrested, imprisoned, or shot as former Communists, Young Communists, officers or supporters of the Soviet government. People of other ethnicities (Lithuanians, Poles, Russians, etc.) would be persecuted for the same reasons. During this period, mostly Jewish men are terrorized. Women and, especially, children would not yet be systematically shot en masse. The initiative to persecute Jews was demonstrated by institutions of the German occupation government (military commandants, operation battalions of the Nazi security police and SD, a bit later — county commissars). Nazi institutions also headed the process of Jewish persecution and murder. From the very onset of the Nazi occupation, Lithuanian administration (county governors, city burgmeisters), Lithuanian police, and battalions of the auxiliary police (the white-armbanders) were involved in this process. (p. 581)

This conclusion and its periodization merit further investigation. The author says almost the same thing when talking about the events in Kaunas county. However there he writes:

In the first weeks of the occupation, until around August 1941[…].” (p. 101)

When writing about Rokiškis, he uses yet another understanding of these “first weeks”:

In the first weeks of the Nazi occupation (from June 27, 1941, to August 14) […] (p. 351).

Why did he need to single out the period until August or even mid-August? The book says nothing about that. But it is well known that, during that time, the Provisional Government of Lithuania was active in Lithuania. In late July, this government was torpedoed by the former Prime Minister Voldemaras’ supporters, who had a much more cruel attitude towards Jews and managed to entrench themselves among the Lithuanian troops that would later massacre Jews. Mid-August is also an important period, as German county commissars — German civilian administration — entered the scene.

The question arises: why does Bubnys only involve this administration up to “mid-July”? No serious data on the condition of Jews getting much worse in August can be obtained. In the summer of 1941, the troops that massacred Jews were simply occupied by terrorizing and destroying the Jewish communities in the big cities, which are not included in Bubnys’ concept of “the province”… In Vilnius, Kaunas, Šiauliai, and Panevėžys, Jews were being massacred from the very beginning of the Nazi occupation in late June, and there are accounts of pogroms and attacks on fleeing Jews from the very start of the war on June 22, 1941.

The characterization using the word “mostly” also employed in the conclusion, is very ephemeral. Only a third of all Lithuanian towns at the time are mentioned in the book. What does this “mostly” mean when there is no data on the other two thirds? Taken by counties, the book provides data on massacres of Jews in the counties of Alytus, Biržai, Kaunas, Kėdainiai, Kretinga, Marijampolė, Mažeikiai, Panevėžys, Raseiniai, Rokiškis, Šakiai, Šiauliai, Švenčionys, Tauragė, Telšiai, Ukmergė, Utena, and Vilkaviškis. No cases from the Lazdijai, Trakai, Vilnius, and Zarasai counties are described, and this may be because the data is very fragmentary. Furthermore, the city of Vilnius is not included in the Vilnius County, whereas the massacres were already underway in Vilnius and it is possible or probably that Jews from one of the countries could have perished together with the Vilnius Jews after fleeing to the city in the vain hope of safety.

The third claim that needs explaining is

During this period, mostly Jewish men are terrorized. Women and, especially, children would not yet be systematically shot en masse.

If we take July 15 to be “mid-July” then we have here a period of less than four weeks. The period was simply too short for the Jew-killing troops to get organized. In the first week, the German army only managed to occupy Lithuania and allow the loyal white-armbanders to rally. Isolation of Jews from Lithuanians took time, too. Yes, in Gargždai, where the first massacres happened, they only took a day. But the German troops, ready to kill, where nearby. In other areas, the process was more complicated. Bubnys does not investigate this issue. However, in the book, there are many cases of Jews being terrorized by bullying actions, forcing them to wear, “kiss” or destroy Soviet symbols. Both Jews and non-Jewish Soviet activists were often murdered in Jewish cemeteries. This was a way to further the “Jews are Communists” Nazi ideology in people’s minds. This was one of the measures taken to isolate Jews from the rest of the society.

Seeing how often Bubnys uses the stereotype (even without going further into asking whether he has grounds for it) of “Communists of various ethnicities” the Nazis managed at leas to entrench this thesis in the minds of historians, such as Arūnas Bubnys (an alternative explanation being that this was internalized by Lithuanian historians in the spirit of minimization, downgrade, obfuscation and distortion of the role of locals in the Holocaust in Lithuania).

Another problem for the murderers to solve was how to break the possible resistance of their victims. This was done by terror, by bullying and murdering rabbis and other respected members of the communities, by forcing the communities to pay indemnities, by forcing people to bear the pain of murder of their children, and other means. Finally, this was done by simply murdering any Jew that happened to cross their way, including refugees and Jews that were allegedly (because they were Jews) “Soviet collaborators”…

Moreover, another measure of terror entails the cases when Jews would be forced to bury the murdered, both Jewish and gentile. There are many examples of this in Bubnys’s book, but the author manages to overlook them in his conclusions. And yes, at first, only male Jews were being murdered. However, one would need several days to find a site and to dig a big enough hole for that… If one started the massacres by killing women and children, one could have expected to see resilient resistance. The men would often decide not to resist in order (in their minds) to protect their women and children. The murderers’ troops were many, but even they barely managed to start murdering men by mid-July. Furthermore, the massacres of men would not always go smoothly. In many areas, a change of Lithuanian administration was necessary after these massacres. Bubnys simply does not investigate this issue. Perhaps he lacks data? Or perhaps that does not fit into the inherited narrative of the “traditional Lithuanian historiography of the Holocaust”? All these tasks in the stages of genocide took time and, therefore, the massacres of the entire communities, including women and children, were delayed until late summer and autumn. However, their fate had already been decided by the time the massacres of the communities’ males started. Furthermore, even in early July, the entire communities of Ylakiai and Plungė Jews were massacred. And this was not an exception, as Bubnys is known to claim in his public presentations. This was but a beginning, and the time of other communities would come soon, and, by the autumn of 1941, non-massacred Jewish communities would be a true rarity in the land of Lithuania.

Hence, the book leaves an ambiguous impression. On the one hand, it is surely impressive in its scope, geography, and sources. It could have been a substantial contribution. On the other hand, due to the author’s attachment to narratives that distort or even deny the Holocaust, uncritical acceptance of some sources, and factual errors, it is a dangerous read for those who do not have sufficient solid knowledge of the Holocaust.

Still, the Education Department of the International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes uses it to educate children and young people of our country. The authority that the International Commission tried to establish by its academic research publications (some truly impressive) is starkly diminished by this book, because, when used as core education material in the name of the Commission, it undermines the very Holocaust education that it uses so much taxpayer money to purportedly teach.

Nationalist academics’ attempts to rewrite history to mitigate local participation in the Holocaust should not be used in education. Indeed, the Republic of Lithuania took a pledge not to do that when it joined the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). Bubnys’s book is in a deeper sense just another publication of the Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania, famous for its historical distortions; but to expect that the publisher would denounce that far-right history-falsifying entry is rather hopeless when the author is also the director of that lavishly state-sponsored center.

Perhaps we could expect now at least an open discussion? I would say that we should expect and even demand a public rebuke from the International Commission. But we probably will not get that, either. Therefore, I would at least like to hope that efforts to “fix the history” will be publicly scrutinized and debated.

◊

In 2012, Evaldas Balčiūnas informed the English reading world about the state glorification of Lithuanian Holocaust collaborator and perpetrator Jonas Noreika, in a series of essays asking why the state commemorates murderers. From 2014 onward, Mr. Balčiūnas was targeted by police and prosecutors for years of legal harassment via kangaroo hearings, charges and court cases. Readers of Lithuanian may access the Lithuanian language version of this review.