An Introduction to Ashkenazic Hebrew and Aramaic

◊

◊

COMPANION TO: THE ASHKENAZIC DICTIONARY

See also Youtube audio selections

Jump to: Contents; Three Types of Ashkenazic; Vowel System; Historical Debates

◊

by Dovid Katz

AUTHOR’S PREVIOUS WORKS ON ASHKENAZIC HEBREW AND ARAMAIC

◊

WORK IN PROGRESS: Draft only (last update: April 2025) of the manual, which originated as course notes for Introduction to Ashkenazic Hebrew (and Aramaic), held as part of the Workmen’s Circle Spring 2021 program of online courses. Comments, corrections and suggestions are welcome (info@yddishculturaldictionary.org).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The author wishes to thank Kolia Borodulin, director of Yiddish programming at the Workmens Circle (NY), for his generosity of spirit and assistance in enabling Ashkenazic (Hebrew and Aramaic) to find its place within wider Yiddish and East European Jewish studies in the Spring 2021 session. Thanks are due to all thirty or so participants in the first course for their contributions; to technical director (and Ashkenazic connoisseur) Boruch Bloom; to Nessa Olshansky-Ashtar (Hamilton, Canada), Prof. Rachel Albeck-Gidron (Bar Ilan Univ.), Philip Schwartz (Wroclaw, Poland), Julia Rets (St. Petersburg, Russia), and Gabriel A. Zuckerberg (New York) for their suggestions and corrections to the evolving manuscript. Siarhej Shupa (Prague) kindly provided the texts to three forgotten Hebrew poems by Yiddish master poet Meyshe Kulbak from the poet’s youth. Thanks also to Joanna (Ashke) Czaban (Krinki, Poland) and Julia Rets for recording bona fide Ashkenazic versions of poems by Bialik, Imber and Tchernichovsky; to Alex Foreman (Chicago, Ill.) for permission to include his exceptional online recordings of Bialik poems, and for his gracious agreement to visit the final session. Other visitors who provided valuable input include Daniel Galay (Leyvik House, Tel Aviv) and Professor Shalom Goldman (Middlebury College). It would be remiss to omit my gratitude to the two major sources of living Ashkenazic in my early life: my late father, poet Menke Katz, and my enrollment in Etz Chaim of Boro Park for part of my elementary school education when it was perhaps the last Ashkenazic (Ivris b’Ivris) speaking school on the planet, with lifelong gratitude to our beloved principal and teachers: Rabbi Israel Dov Lerner and his teaching staff, including Mrs. Adelman, Mrs. Klayman, Mrs. Koppelman, Mr. Ostrow and Rabbi Sonnenschein. Over the years, I have benefited much from discussions on Ashkeanzic issues with Prof. Ghil’ad Zuckermann and the late Professor Benjamin Harshav.

Some of the material herein hails from three decades of Yiddish expeditions in Eastern Europe, for which the beginnings of an atlas and video archive are online. Spinoffs from the Workmens Circle course include, in addition to the present manual, a mini-dictionary and youtube playlist. Naturally, full responsibility for errors, shortcomings and opinions expressed, implicitly or otherwise, rests with the author alone.

◊

Liturgical Samples Quickfinder:

HAFTORAH BLESSINGS

MOURNER’S KADDISH (FORMAL; INTIMATE; MORE INTIMATE)

PASSOVER: FOUR QUESTIONS; TEN PLAGUES; KHAD GADYO

◊

Hebrew Poetry Quickfinder:

H.N. BIALIK ♫

Y.L. GORDON

N.H. IMBER ♫

RABBI A.E. KAPLAN ♫

M. KULBAK

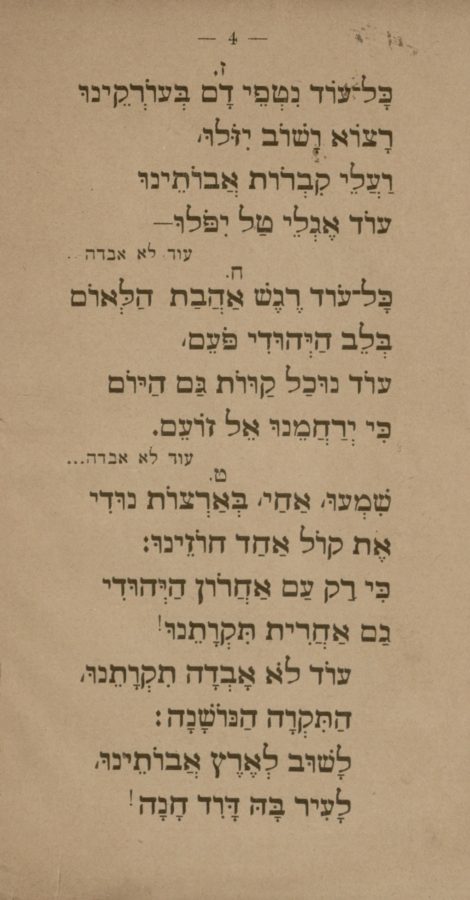

S. TCHERNICHOVSKY ♫

◊

ASHKENAZIC MINI-DICTIONARY

◊

◊

- ☰Contents☰

- ◊

-

◊

-

The Sounds of Ashkenazic

-

and their

-

Cultural Content

- ◊

- Vocalism of Standard Ashkenazic (and of principal Southern and Northern Dialects)

- ◊

- Consonantism

- ◊

- Three Major Types of Ashkenazic:

- ◊

- Ashkenazic Stressblockers

- ◊

- Ashkenazic Variability

- Rhythm

- Rhyme

- Dialect

- Vernacularization

- Devernacularization

- The Pleasure Principle

- ◊

- ◊

- Grammar and Usage

- ◊

- Morphology

- Lexicon and Semantics

- חפץ√

- Unmarked everyday forms

- Jewish cultural content

- ◊

- Aspects of Usage

- Reflexive

- First person variations

- Second person address

- Prepositional use

- Relative pronouns

- Possession via genitive

- Article placement in nominal compounds

- Retention of definite article with preposition

- Copula

- ◊

- ◊

- Texts

- ◊

- ◊

- Religious and Liturgical

- ◊

- Prayers

- ◊

- Two of the Post-Haftorah Blessings

- ◊

- Passover Seyder Selections

- The Four Questions (bilingual Yiddish-Hebrew)

- The Ten Plagues

- Khad Gadyo

- *

- Mourner’s Kaddish

- Formal Kaddish (in Ashke-1)

- Intimate Kaddish (in Ashke-2)

- More Intimate Kaddish (in Ashke-3)

- Composite Kaddish

- ❊

- Modern Hebrew Poetry

- ◊

- H.N. Bialik

- Loy Bayóym V’lóy Baláylo

- in Standard Ashkenazic

- in Southern (Warsaw)

- in Northern (Vilna)

- (The author’s Yiddish version)

- ◊

- B’ír Haharéygo

- Bisshuvosi

- *

- Y. L. Gordon

- Hasús Vəhasís

- *

- N.H. Imber

- Hatikvoh

- in Standard Ashkenazic

- in Southern (Warsaw)

- in Northern (Vilna)

- Original poem (with Standard Ashkenazic transcription)

- *

- Meyshe Kulbak

- Gan Stov

- Day Ekhovey

- Bəaflúlis Leyl

- *

- Sh. Tchernichovsky

- Sákhki Sákhki

- (Y.Y. Shvarts’s Yiddish translation)

- *

- ◊

- ◊

- ◊

- ◊

- Appendices

- Historical and sociological debates conceived as separate from the Manual itself. It is hoped that readers of the most diverse viewpoints on these contentious subjects will find something of interest or use in the Manual per se. The author’s writings on Ashkenazic are available online.

-

◊

-

Appendix 1: Daniel Persky: Excerpt from Correct Hebrew (1962).

-

Appendix 2: S. Burnshaw, T. Carmi et al (eds): The Hebrew Poem Itself (1966).

-

Appendix 3: Miryam Segal: A New Sound in Hebrew Poetry (2010).

-

Appendix 4: Itamar Even-Zohar: The Emergence of a Native Hebrew Culture in Palestine: 1882-1948 (1997).

-

Appendix 5: Shelomo Morag: The Emergence of Modern Hebrew: Some Sociolinguistic Perspectives (1993).

-

Appendix 6: Dovid Katz: Words on Fire. The Unfinished Story of Yiddish (2007).

-

Appendix 7: Assertion on late 19th — early 20th century First Aliyah Ashkenazic as native spoken language (and the first manifestation of vernacular Hebrew in c. two millennia).

-

Appendix 8: A. M. Kaiser’s essay on the campaign for “Sephardic” Hebrew in London (from his Ba undz in Vaytshepl, London 1944, pp. 68-70).

-

Appendix 9: From Lewis Glinert’s “Prologue” to his The Joys of Hebrew (1992)

◊

Mini-Dictionary

◊

◊◊

Vowels

NOTE: For readers interested in the cognates within the system of pan-Yiddish vocalism, each vowel’s ID is added at the end of the entry. The system is explained in various works on Yiddish linguistics and dialectology (e.g. here).

◊

אַ (and אֲ when not deleted)

a

אַתְּ; אַתָּה, גַּן; נַחַתֿ, צַד, קַל, רַק.

COGNATE IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 11 (A1)

◊

אָ (and אֳ when not deleted)

o ([ɔ])

אָדָם; הָלַךְ; כְּּבוֹדָהּ; לְבָנָה; נְתַֿנְיָהוּ; עָשָֹה; עָתִֿיד; שָׁם

Aide-mémoire: קָמָץ or קוּמְצָא דְפוּמָא = ‘contracting of the mouth’ (≠ פַּתָֿח or פַּתְֿחָא דְּפוּמָא ‘opening wide of the mouth’).

Note: In Southern dialects realized as u in open syllables, o in closed syllables: אָדָם = udom. It is also realized as o in Southern dialects in the case of possessive hey with mapik: כְּבוֹדָהּ = kvoydo. Cf. אִשָּׁה ishu ‘woman’ ≠ אִישֶָׁהּ isho ‘her husband’.

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 12 (A2) IN OPEN SYLLABIES; VOWEL 41 (O1) IN CLOSED SYLLABLES

◊

(אֱ/) אֶ

e ([ε])

אֶל; בְּדִיעֶבֶד; חֶסֶד; מֶלֶךְ; מְפוּרסֶמֶתֿ; מְרַחֶפֶתֿ; תִּפְאֶרֶתֿ

Note: In Southern dialects realized as ey [ej] in (primevally) stressed open syllables, but as e ([ε]) in syllables to which originally ultimate stress shifted to penultimate in Ashkenazic: חֶסֶד = khéysed, but אֱמֶתֿ = émes.

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 25 (E5) IN OPEN SYLLABIES; VOWEL 21 (E1) IN CLOSED SYLLABLES

◊

אֵ(י)

ey ([ej])

אֵל; אֵלֶה; בְּהֵמָה; בִּשְׁלֵמוּתֿ; הֵם; חֵשֶׁק; כֵּן

Note 1: In Southern dialects, realized as ay ([aj]): חֵשֶׁק = kháyshek; הֵם = haym. This is however not the case in Southeastern (Ukrainian [Podolian, Volynian, Bessarabian) Hebrew which follows the north in this vowel.

Note 2: In (esp. early) modern Israeli Hebrew, the realization [ey] (instead of collapsed Sephardic/Israeli [ε]) persisted even in the speech of major national leaders in a series of phonemic environments (e.g. [éylε] for [έlε] ‘these’; [beyt dín] for [bεt-dín] ‘court’, [yisraéyl] for [yisraέl] ‘Israel’). The phenomen is still encountered in some Israeli sectors, and in even more so in diasporic attempts at Israeli pronunciation where there are deep Ashkenazic roots that in the case of this vowel persist without any major sociolinguistic strings (in sharp contrast to its back-vowel counterpary diphthing [oy] which has became a firm, and at times highly emotive, Haredism marker, Yiddish marker, shtetl marker etc, in the eyes of disparate beholders).

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 22 (E2) WHEN LONG AND VOWEL 21 (E1) WHEN SHORT IN ALL DIALECTS

◊

אִ(י)

i (/iy [ij]; [ī])

אִם, לִפְנֵי; מִפִּי; יְלִיד; כִּתָּה; קִיר; קְלִיפָּה

Note: The southern dialects of East European Yiddish and Ashkenazic, comprising the major groups of Mideastern (“Polish”) and Southeastern (“Ukrainian”) preserve a further length distinction between i sounds on a generally predictable basis based on the ancient Tiberian forms. Cf. e.g. Southern shívo (‘seven’ or ‘the seven-day mourning period) vs. ksí:vo (‘handwriting’). These contrasts, reflecting ancient Tiberian oppositins long after change of syllabic structure, are only observable in Ashke-2 and Ashke-3, and are generally lost in synchromically unstressed position.

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 32 (I2) WHEN LONG AND VOWEL 31 (I1) WHEN SHORT IN ALL DIALECTS

◊

(אֹ /) אוֹ

oy ([ɔj])

חוֹשֶֶׁךְ; חֲלוֹמוֹתֿ; כְּבוֹדוֹ; סוֹדוֹתֿ; קוֹלוֹתֿ, שׁוֹמֵר; תּוֹרָה

Note 1: In Northern dialects: ey ([ej]: קוֹלוֹתֿ = keyleys; חֲלוֹמוֹתֿ = khaleymeys.

Note 2: In the United States, Britain and other English speaking countries, an o: (ou) realization (“o as in home”) often replaced the East European oy (/Northern ey) realizations of holem. This was often due to sociolinguistic factors (e.g. embarrassment over oy phonemes considered “funny” and “greenhorn” in some English speaking countries; also: identification with Haredi religious culture and a desire to stay away from its phonetic hallmarks). Similar realizations were found in older German Jewish traditions that predated East European mass migration in the United States and Great Britain and made for a conveniently popular “way out.” See for example, the transcription of the mourner’s kaddish in Dr. Philips’ prayerbook in the earlier and mid twentieth century by Hebrew Publishing Company.

Note 3: In traditional Ashkenazic society, every male studies the classical Accents (trop) and their application to his Bar Mitzvah day’s readings from the Pentateuch and Haftorah, engendering an intimate familiarity that reinforces that of all men and women with Ashke-1 by virtue of enjoing Sabbath and holiday Torah readings by a reader who keeps strictly to classican accentuation.

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 42 (O2) IN OPEN SYLLABIES; VOWEL 41 (O1) IN CLOSED SYLLABLES

◊

(אֻ /) אוּ

u

גְּדוּלָה; גּוּפאָ; הוּא; כְּלוּם; סְעוּדָה; תְּחוּם; קוּף

Note: In Southern dialects the realization is i (whether long or short dependent on position and dialect): הוּא = hi(:), גְּדולָה = gedilu.

Note: The southern dialects of East European Yiddish and Ashkenazic, comprising the major groups of Mideastern (“Polish”) and Southeastern (“Ukrainian”) preserve a further length distinction between historic u sounds on a generally predictable basis based on the ancient Tiberian forms. Fonrting and unrounding has resulted overthe centuries in the realizations being , synchronmically speaking, among i vowels in recent centuries. Cf. e.g. Southern khípu (‘traditional wedding canopy’)) vs. bí:shu (‘disgrace’). These contrasts, reflecting ancient Tiberian oppositins long after change of syllabic structure, are only observable in Ashke-2 and Ashke-3, and are generally lost in synchromically unstressed position.

COGNATES IN YIDDISH VOCALISM: GENERALLY VOWEL 52 (U2) WHEN LONG AND VOWEL 51 (U1) WHEN SHORT IN ALL DIALECTS

◊

“Diphthong 34 via Hiatus”

As in the Semitic Component in Yiddish, there is a pan-Ashkenazic reflex of Semitic etymons that emerges, in effect, as an additional vowel, consistently yielding systematic correspondences between Ashenazic/Yiddish dialects as is the nature of derivatives from a common protolanguage. Vowel 34 in the pan-Yiddish system, most frequently in the Germanic Component in Yiddish a reflex of Middle High German long î , e.g. fayn ‘fine’, váyn ‘wine’, with the usual pan-Yiddish systematic dialectal differentiation, emerging e.g. as ā in Mideastern (“Polish-Hungarian”) Yiddish, yielding fān, vān, and a in much Southeastern (“Ukrainian-Bessarabian”) Yiddish, yielding fan, van.

The “Vowel 34 effect” usually emerges in resolution of vocalic hiatus, most frequently the sequencing of a pasakh and khatof-pasakh, shewa, and occasionally of other vowels in sequence. Very early in Ashkenazic linguistic history, the loss of consonantal realization of alef and ayin and the ensuing hiatus triggered migration to the usually Germanic-derived lexicon exhibiting Vowel 34.

ay

גַּאֲוָה; דְּאָגָה; טַעֲנָה; מַאֲדִים; מַאֲמִין; מַהַפַּךְ; מַעֲשֶׂה; תַּעֲנוּג

Note 1: As a wider Ashkenazic phenomenon, it is frequently the case that a lexical item for which “diphthong 34” is reflected consistently across language varieties descending from the entire breadth of historic Ashkenaz. One implication is interdialectal predictability, as is common for varieties deriving from a protolanguage or earlier common ancestor variety state. So, for example,if one hears or sees maymin as the Northeastern (“Lithuanian”) Ashkeanzic rendition, it can be predicted that it will surface empirically as mamin in the Southeastern (“Ukrainian”) varieties and má:min in the Mideastern (“Polish”) Ashkenazic.

Note 2: Occasionally, in tandem with the situation in Yiddish, with which Ashkenazic interacts within the Ashkenazic polysystem (in the sense of Prof. Even-Zohar,ד development of the term and its features) in myriad ways that add layers to the lexicon and semantics of any of the donor varieties (stock languages in Max Weinreich’s terminology). Uniquely Ashkenazic oppositions are not infrequently observed, for example historical שְׁאֵלָה (‘question’), yielding Ashkenazic sháylo in the sense of a question asked of a rabbi or other authority concerning permissability vs. forbidden status (e.g. about whether an item is kosher) and in a number of emotive and homey contexts (e.g. in an exclamation along the lines of “Wow, now that is a question!”). This contrasts with sh(ə)éylo (‘question of any kind’). That contrast of what are now effectively two lexical items, of general sh(ə)éylo vs. much more nuanced sháylo is mirrored precisely in the southern dialects of Eastern Yiddish, yielding the cognate opposition of sh(ə)áylu vs. shá(:)lu.

COGNATE TO YIDDISH VOWEL 34

◊

◊◊

Consontantism

תּ = t

תֿ = s

שַׁבָּתֿ, לָתֵֿתֿ, תְּרוּמוֹתֿ

Classically spirantized tof (historically θ, or th as in thought), is pronounced s. Because of many students’ difficulty in averting its collapse with plosive תּ as unitary in Israeli, the spirantized ת is marked in this manual with the classical rofe over the letter denoting spirantized s: תֿ.

◊

◊

The Three Basic Types of Ashkenazic Hebrew (and Aramaic)

◊

„מַלְכוּתֿ אֲחַשְׁוֵרוֹשׁ“

(Esther 3:6, 9:30)

◊

„לֵב טוֹב“

(Mishnah Avoth 2: 9)

◊

◊

Ashke-1 (′נוּסַח א)

Formal Biblical Reading (and other formal pointed-text contents throughout Ashkenazic history)

Formal Hebrew Speech (schools, conferences, etc from 19th century)

◊

Features:

Word-final stress where denoted by Tiberian accentuation (i.e. accentuation identical with classical), with no posttonic vowel reduction:

Standard Ashkenazic: malkhús akhashveyróysh; leyv toyv

Southern (“!Polish”): malkhís akhashvayróysh; layv toyv

Northern:( “Lithuanian”): malkhús akhashveyréysh; leyv teyv

Old Western: malkhús akhashveyróush; leyv touv

◊

Ashke-2 (′נוּסַח ב)

General Prayer and Recitation (from times of medieval stress shift onward)

Bible Study (& other pointed texts in educational context)

Modern Hebrew Poetry (from the early 19th century onward)

Revived Hebrew Speech (in maskilic and original East European Hebraist and Zionist circles and education alongside more formal variants in line with Ashke-1)

◊

Features:

Penultimate stress (corresponding to classical ultimate and penultimate alike) with no posttonic vowel reduction:

Standard Ashkenazic: málkhus akhashvéyroysh; leyv toyv

Southern (“!Polish”): málkhis akhashváyroysh; layv toyv

Northern: (“Lithuanian”) [sample]: málkhus akhashvéyreysh; leyv teyv

Old Western: málkhus akhashvéyroush; leyv touv

◊

Talmudic and Kabbalistic Study (with unpointed texts)

Intimate Prayer

Semitic Component in Yiddish

◊

Features:

Penultimate stress with posttonic reduction and Closed Syllable Shortening

Standard Ashkenazic: málkhəs akhashvéyrəsh; lev tov (/lef tov)

Southern (“!Polish”): málkhəs akhashváyrəsh lev tof (/lef tof)

Northern: (“Lithuanian”): málkhus akhashvéyrəsh; lev tov (/lef tov)

Old Western: málkhəs akhashvéyrəsh; lev tov◊

◊

◊

Major Blockers of Penultimate Stress

◊

1

Shewa as a rule is not stressed (and is in fact often deleted):

בְּכוֹר [bəkhóyr], Northern: [bəkhéyr], SCY/Tal (=Semitic Component in Yiddish and Talmudic studies): [bəkhór] or [pkhór] (‘the eldest son’)

גְּבוּל [gəvúl], Southern: [gəvíl], SCY/Tal: [gvúl], Southern: [gvíl] (‘border’)

כְּמוֹ [kəmóy], Northern: [kəméy] (‘like’, ‘similar to’)

◊

2

Prefixed non-root morphemes are generally not stressed. These include:

Definite articles:

הַבֵּן [habéyn], Southern [habáyn]; when cited in SCY/Tal: [habén] (‘the son’)

הַיוֹם [hayóym], Northern [hayéym] ; in SCY/Tal: [hayóm] (‘the day’; ‘today’)

הָעָם [hoóm], Southern [hu:óm] (‘the nation’)

◊

Prepositions:

לַשֵׁם [lashéym], Southern: [bəsháym]; SCY/Tal: [lashém] (‘to the name’)

בַּסוֹף [basóyf], Northern: [baséyf]; SCY/Tal: [basóf] (‘at the end’)

מִכָּל [mikól] (‘from all’)

◊

Relativizing pronoun:

שֶבָּא [shebó], Southern: [shebú:] (‘that came’, ‘who came’)

שֶאֵין [she-éyn], Southern: [sheáyn], SCY/Tal: [she-én] (‘that is not’, ‘that does not’)

◊

3

‘Sacred Stress’:

אָמֵן [oméyn], Southern: [umáyn] (‘Amen’)

יְיָ [adoynóy], Northern: [adeynóy], SCY/Tal: [adənóy] (‘God’, ‘The Lord’); also (to avoid uttering the sacred: [adoyshém], Northern: [adeyshém}, SCY/Tal: [adəshém]

אֱלֹהִים [eloyhím], Northern: [eleyhím]. SCT/Tal: [eləhím] (‘God’)

יעמוד [yaamóyd], Northern: [yaaméyd] (‘There will rise’ [calling up the next to say the blessings over the portion of the Torah about to be read]

◊

4

Three-letter Acronymics in the Nominal Templates CaCáC and CaCó:

חב″ד [khabád] (Chabad [Lubavitch Hasidism]); {< חכמה בינה דעתֿ}

חג″תֿ [khagás] (Southern / Non-Litvak, ‘real’ Hasidim); {< חסד גבורה תפארתֿ}

חז″ל [khazál] (‘the great sages of blessed memory’) {< חכמינו זכרונם לברכה}

רמ″א [ramó], Southern: [ramú] (the Ramo, Rabbi Moses Isserles) {< ר′ משה איסרליש}

רח″ש [rakhásh] (expenses of hiring the rabbi, cantor and beadle for wedding or other religious event) {< רב חזן שמש}

של″ה [shaló], Southern: [shalú:] (Shney Lukhoys Habris = Rabbi Isaiah Horowitz) {< שני לוחות הברית}

שס″ה [shasó], Southern: [shasú:] (‘365 [days of the solar calendar’) {< ‘ש’+ס’+ה}

תנ″ך [tanákh] (‘the Hebrew Bible’) {< תורה נביאים כתֿובים}

Note: the rule does not generally hold for other acronyms which tend to follow the penultimate pattern, e.g. רש″י (Ráshi; SCY(Tal): Ráshə), מלבי″ם (Málbim), יעב″ץ (Yá(y)vits), רמב″ם (Rámbam = Maimonides), מהרש″א (Mehársho). The case of רמב″ן (rambán = Moses Ben Nachman = Nachmanides) is generally explained by the need for sharp contrast with the acronym of Maimonides.

◊

5

Contrastive Stress

Ultimate stress may be invoked for the sake of contrast, e.g.

אִשָּה [ísho] ‘woman’ vs. אִישָהּ [ishó] ‘her husband’;

מַלְׁכָּה [málko] ‘queen’ vs. מַלְׁכָּהּ [malkó] ‘her (/it’s f.) king’.

Note that in southern dialects, the possessive הּ (hey with ,mapik) is rendered o (a per closed syllable rules, yielding Yiddish vowel 41), contrasting with u: for komets in open syllable, giving ishu: ‘woman’ vs. isho ‘her husband’, malku ‘queen’ vs. malko (‘her (/it’s f.) king’).

◊

◊

◊

Ashke-3: Semitic Component in Yiddish; Study and exposition of Hebrew and Aramaic texts of Bible, Talmud, Kabbalah (SCYT)

“Living Language and Unpointed Texts”

Closed Syllable Shortening:

k(ə)lol, k(ə)lolim → klal, klolim

leyts, leytsim → lets, leytsim,

soyfeyr, soyfrim → soyfer, sofrim

Note: Quantitatively, the oral and “read” (whether or not out loud) use of Ashke-3 over the last millennium is exponentially higher than the others combined, including entire days of intensive study of unpointed texts, and for many also heavily encroaching in some pointed) prayer texts. This is verily the language of everyday life (the Semitic Component of the full daily language Yiddish). The rise of Ashke-2, primarily in the hands of the great Hebrew poets of nineteenth and early twentieth century, stands in stark counterpoint to the less formal (most widely used) Ashke-3 and the more formal Ashke-1 (mastered by Torah readers and other scholars). Beyond posttonic reduction of vowels to various degrees of shewa, the stressed syllables are processed by Closed Syllable Shortening. For Yiddish linguists: In closed syllables, Vowel 12 (A2) ⇒ 11 (A1), Vowel 22 (E2) ⇒ 21 (E1), and Vowel 42 (O2) ⇒ 41 (O1). Given the derivation of (much of) all Yiddish dialects (and their Semitic Components and Ashkenazic traditions) from a proto language, it is possible to predict from these formulas the outcome in most cases within any given dialect.

| Ashke-1

(Bible, formal prayer) |

Ashke-2

(Some prayer, MHP) |

oAshke-3

(SCY; unpointed text study)

|

|

| דָּם (komots) | dom | dom | dam |

| שֵׁם (tseyrey) | sheym (/S: shaym) | sheym (/S: shaym) | shem |

| סוֹד (khoylom) | soyd (/N: soyd) | soyd (/N: seyd) | sod |

Note: In Yiddish as in study of Talmud and other unpointed text, the Closed Syllable Shortening rule produces the characteristic alternations of three principal vocalic pairs:

(1) o ∼ a: pl. protim (/S: pru:tim) ‘details’ ∼ sg. prat

(2) ey ∼ e: shed ‘ghost’ ∼ pl. sheydim (/S: shaydim)

(3) oy ∼ o: soyfer (/N: seyfer) ∼ pl. sofrim

◊

◊

Prayers: Three Basic Types

(1) Miléyl (with Ashkenazic penultimate accentuation).

(2) Milrá (with word-final stress where required by classical Tiberian accentuation).

(3) Synthesis of the two.◊

:Example from two of the blessings following the Haftorah reading

רַחֵם עַל צִיּוֹן כִּי הִיא בֵיתֿ חַיֵּינוּ, וְלַעֲלוּבַתֿ נֶפֶשׁ תּוֹשִׁיעַ בִּמְהֵרָה בְיָמֵינוּ: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, מְשַׂמֵּחַ צִיּוֹן בְּבָנֶיהָ:

שַׂמְּחֵנוּ יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ בְּאֵלִיָּהוּ הַנָּבִיא עַבְדֶּךָ, וּבְמַלְכוּתֿ בֵּיתֿ דָּוִד מְשִׁיחֶךָ, בִּמְהֵרָה יָבֹא וְיָגֵל לִבֵּנוּ. עַל כִּסְאוֹ לֹא יֵשֵׁב זָר וְלֹא יִנְחֲלוּ עוֹד אֲחֵרִים אֶת כְּבוֹדוֹ. כִּי בְשֵׁם קָדְשְׁךָ נִשְׁבַּעְתָּ לֹּו שֶׁלֹּא יִכְבֶּה נֵרוֹ לְעוֹלָם וָעֶד: בָּרוּךְ אַתָּה יְיָ, מָגֵן דָּוִד:

(1) Miléyl (with Ashkenazic penultimate accentuation):

Rákheym al tsíyoyn ki hi véys khayéynu, vəlaalúvas néfesh toyshíya bimhéyro bəyoméynu. Bórukh áto adoynóy, mesaméyakh tsíyoyn bəvoného.

Samkhéynu Adoynóy eloyhéynu bəEyliyóhu hanóvi avdékho, uvmálkhus beys Dóvid məshikhékho, bimhéyro yóvoy, vəyógeyl libéynu. Al kísoy loy yéysheyv zor, vloy yinkhálu oyd akhéyrim es kvóydoy, ki vəshem kódshəkho nizhbáto loy, shelóy yíkhbe néyroy ləóylom vóed. Bórukh áto Adonóy, mógeyn Dóvid.

(2) Milrá (with word-final stress where required by classical Tiberian accentuation):

Rakhéym al tsiyóyn ki hi véys khayéynu, vəlaaluvás néfesh toyshíya bimheyró bəyoméynu. Borúkh ató adoynóy, mesaméyakh tsiyóyn bəvoného.

Samkhéynu Adoynóy eloyhéynu bəEyliyóhu hanoví avdékho, uvmalkhús beys Dovíd məshikhékho, bimheyró yovóy, vəyogéyl libéynu. Al kisóy loy yéysheyv zor, vloy yinkhalú oyd akheyrím es kvoydóy, ki vəshém kodshəkhó nizhbáto loy, shelóy yikhbé neyróy ləoylóm voéd. Borúkh ató Adonóy, mogéyn Dovíd.

(3) Synthesis of the two:◊

Rakhéym al tsíyoyn ki hi véys khayéynu, vəlaaluvás néfesh toyshíya bimheyró bəyoméynu. Borúkh ató adoynóy, mesaméyakh tsíyoyn bəvoného.

Samkhéynu Adoynóy eloyhéynu bəEyliyóhu hanóvi avdékho, uvmálkhús beys Dóvid məshikhékho, bimheyró yovóy, vəyogéyl libéynu. Al kísoy loy yéysheyv zor, vloy yinkhálu oyd akhéyrim es kvoydóy, ki vəshém kodshəkhó nizhbáto loy, shelóy yikhbé néyroy ləoylóm voéd. Borúkh ató Adonóy, mogéyn Dovíd.

◊

◊

Mourner’s Kaddish

◊

קדיש יתֿום

- יִתְֿגַּדַּל וְיִתְֿקַדַּשׁ שְׁמֵיהּ רַבָּא, בְּעָלְמָא דִּי בְרָא כִרְעוּתֵֿהּ וְיַמְלִיךְ מַלכותֵֿהּ בְּחַיֵּיכוֹן וּבְיוֹמֵיכוֹן וּבְחַיֵּי דְכָל בֵּיתֿ יִשְׂרָאֵל בַּעֲגָלָא וּבִזְמַן קָרִיב וְאִמְרוּ אָמֵן:

- יְהֵא שְׁמֵיהּ רַבָּא מְבָרַךְ לְעָלַם לְעָלְמֵי עָלְמַיָּא:

- יִתְֿבָּרַךְ וְיִשְׁתַּבַּח וְיִתְֿפָּאַר וְיִתְֿרוֹמַם וְיִתְֿנַשֵּׂא וְיִתְֿהַדָּר וְיִתְֿעַלֶּה וְיִתְֿהַלָּל שְׁמֵהּ דְּקֻדְשָׁא בְרִיךְ הוּא:

- לְעֵלָּא מִן כָּל בִּרְכָתָֿא שִׁירָתָֿא תִּשְׁבְּחָתָֿא וְנֶחָמָתָֿא דַאֲמִירָן בְּעָלְמָא וְאִמְרוּ אָמֵן:

- יְהֵא שְׁלָמָא רַבָּא מִן שְׁמַיָּא וְחַיִּים עָלֵינוּ וְעַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל וְאִמְרוּ אָמֵן:

- עֹשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם בִּמְרוֹמָיו הוּא יַעֲשֶׂה שָׁלוֹם עָלֵינוּ וְעַל כָּל יִשְׂרָאֵל וְאִמְרוּ אָמֵן:

◊

I: FORMAL (ASHKE-1)

- Yisgadál v’yiskadásh shméy rabó

- B’olmó di vró khiruséy v’yamlíkh malkhuséy

- B’khayeykhóyn uv’yoymeykhóyn uvkháyey d’khol Beys Yisroéyl

- Boagoló uvizmán korív v’ímru: OMÉYN

- Y’HÉY SHMÉY RÁBO MEVÓRAKH, L’ÓLAM UL’ÓLMEY OLMAYÓ

- ●

- Yizborákh v’yishtabákh v’yispoár v’yisroymám v’yisnaséy

- V’yishadár v’yisalé v’yishalól shméy d’kudshó: BRIKH HU

- ●

- L’éylo min kol birkhosó v’shirosó

- Tushb’khosó v’nekhemosó, d’amíron b’ólmo v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Y’héy shlómo rábo min shmáyo v’kháyim

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisroyéyl vimrú: OMÉYN

- ●

- Oysé sholóym bimroymóv, hu yaasé sholóym

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisroyéyl vimrú: OMÉYN

- ● ● ●

◊

II: INTIMATE (ASHKE-2)

◊

Rendition in Litvish (Northeastern / Litvak) by Yeynesn Felendler

◊

- Yizgadal v’yiskadash shméy rábo

- B’ólmo di vró khirúsey v’yámlikh malkhúsey

- B’khayéykhoyn uv’yoyméykhoyn ufkháyey d’khol Beys Yisróeyl

- Boagólo uvizmán kóriv v’ímru: OMÉYN

- Y’HÉY SHMÉY RÁBO MEVÓRAKH, L’ÓLAM UL’ÓLMEY OLMÁYO

- ●

- Yizbórakh v’yishtábakh v’yispóar v’yisróymeym v’yisnásey

- V’yishádor v’yisále v’yishálel shméy d’kúdsho: BRIKH HU

- ●

- L’éylo min kol birkhóso v’shiróso

- Tushb’khóso v’nekhemóso, d’amíron b’ólmo v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Y’héy shlómo rábo min shmáyo v’kháyim

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisróeyl v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Óyse shóloym bimróymov, hú yá(a)se shóloym

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisróəl v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ● ● ●

◊

III: MORE INTIMATE (ASHKE-3)

- Yizgadal v’yiskadash shméy rábo

- B’ólmə di vró khirúsəy v’yámlikh malkhúsey

- B’khayéykhən uv’yoyméykhən ufkháyey d’khol Beys Yisróəl

- Boagólə uvizmán kórəv v’ímru: OMÉYN

- Y’HÉY SHMÉY RÁBO MEVÓRAKH, L’ÓLAM UL’ÓLMEY OLMÁYO

- ●

- Yizbórakh v’yishtábakh v’yispóar v’yisróyməm v’yisnásə

- V’yishádor v’yisálə v’yisháləl shméy d’kútshə: BRIKH HU

- ●

- L’éylo min kol birkhósə v’shirósə

- Tushb’khósə v’nekhemósə, d’amírən b’ólmə v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Y’héy shlómə rábə min shmáyə v’kháyəm

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisró(ə)l v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Óyse shóləm bimróyməv, hú yásə shóləm

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisró(ə)l v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ● ● ●

◊

IV: TYPICAL COMPOSITE

- Yizgadál v’yiskadásh shméy rabó

- B’ólmo di vró khirúsəy v’yámlikh malkhúsey

- B’khayéykhən uv’yoyméykhən ufkháyey d’khol Beys Yisróəl

- Boagólə uvizmán kórəv v’ímru: OMÉYN

- Y’HÉY SHMÉY RÁBO MEVÓRAKH,L’ÓLAM UL’ÓLMEY OLMÁYO

- ●

- Yizbórakh v’yishtábakh v’yispóar v’yisróymeym v’yisnásə

- V’yishádor v’yisálə v’yisháləl shméy d’kútsho: BRIKH HU

- ●

- L’éylo min kol birkhóso v’shiróso

- Tushb’khóso v’nekhemóso, d’amíron b’ólmə v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Y’héy shlómo rábo min shmáyo f’kháyəm

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisró(ə)l v’ímru: OMÉYN

- ●

- Óyse shóləm bimróymov, hú yáse shóləm

- Oléynu v’al kol Yisró(ə)l v’ímru: OMÉYN

◊

Passover Seyder Selections

ד′ קַשְׁיוֹתֿ

Traditional Hebrew Yiddish “sandwich” of the original text embedded in Yiddish introductory and concluding text. From the Vilna area but in Standard Ashkenazic and Yiddish pronunciation:

◊

If one’s father is sitting at the Peysakh table:

טאַטע! כ′ל בײַ דיר פרעגן די פיר קשיותֿ!

If not:

רבותֿי! כ′ל בײַ אײַך פרעגן די פיר קשיותֿ!

![]()

די ערשטע קשיא איז:

מַה נִּשְׁתַּנָה הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה מִכָּל הַלֵּילוֹתֿ?

Ma nishtáno haláylo hazé, mikól haléyloys?

פאַרוואָס איז אָטאָ די נאַכט פון פֵּסַח אַנדערש פון אַלע נעכט פון אַ גאַנץ יאָר?

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹתֿ

shepkhól haléyloys

אַז אַלע נעכט פון אַ גאַנץ יאָר

אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין חָמֵץ וּמַצָּה

Ónu óykhlin khómetys umátso

עסן מיר סײַ חָמץ סײַ מַצה

הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה

Haláylo hazé

אָבער — אָטאָ די נאַכט פון פֵּסַח

כֻּלּוֹ מַצָּה!

Kúloy mátso

עסן מיר — נאָר מצה!

![]()

די צווייטע קשיא איז:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹת

shepkhól haléyloys

אַז אַלע נעכט פון אַ גאַנץ יאָר

אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין שְׁאָר יְרָקוֹת

Ónu óykhlin shəòr-yerókoys

עסן מיר אַלערלייאיקע גרינסן

הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה

Haláylo hazé

אָבער — אָטאָ די נאַכט פון פֵּסַח

מָרוֹר!

Móroyr!

עסן מיר נאָר — ביטערע קרײַטעכער!

![]()

די דריטע קשיא איז:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹתֿ

shepkhól haléyloys

אַז אַלע נעכט פון אַ גאַנץ יאָר

אֵין אָנוּ מַטְבִּילִין אֲפִילוּ פַּעַם אֶחָתֿ

Eyn ónu madbílin, afílu páam ékhos

טונקען מיר ניט אײַנעט דעם עסן, אַפילו קיין איין מאָל אויכעט ניט

הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה

Haláylo hazé

אָבער — אָטאָ די נאַכט פון פֵּסַח

שְׁתֵּי פְעָמִים!

Shtéy peómim!

טונקען מיר אײַנעט דעם עסן — צוויי מאָל: איין מאָל ציבעלע אין זאַלץ⸗וואַסער, און איין מאָל — כריין אין חרוסתֿ.

![]()

די לעצטע קשיא איז:

שֶׁבְּכָל הַלֵּילוֹתֿ

shepkhól haléyloys

אַז אַלע נעכט פון אַ גאַנץ יאָר

אָנוּ אוֹכְלִין בֵּין יוֹשְׁבִין וּבֵין מְסֻבִּין

Ónu óyklin beyn yóshvin uveyn mesúbin

עסן מיר סײַ זיצנדיק סײַ אָנגעלענטערהייט

הַלַּיְלָה הַזֶּה

Haláylo hazé

אָבער — אָטאָ די נאַכט פון פֵּסַח

כֻּלָּנוּ מְסֻבִּין!

Kulónu mesúbin

עסן מיר אַלע נאָר — אָנגעלענטערהייט!

![]()

If one’s father is sitting at the Peysakh table:

טאַטע! גיב מיר אַן ענטפער אַף די פיר קשיותֿ!

If not:

רבותֿי! גיט מיר אַן ענטפער אַף די פיר קשיותֿ!

![]()

עֲבָדִים הָיִינוּ וכו′

◊

◊

Passover Seyder Recitation of the Ten Plagues

דָּם dom

צְפַרְדֵּעַ tsfardéya (\דרומי: tsfardáya)

כִּנִּים kínim

עָרוֹב óroyv (\דרומי: uróyf; צפוני: óreyv)

דֶּבֶר déver (\דרומי: déyver)

שְׁחִין sh(ə)khín

בָּרָד bórod (דרומי: búrot)

אַרְבֶּה árbe

חֹשֶׁךְ khóyshekh (צפוני: khéyshekh)

מַכַּתֿ בְּכוֹרוֹתֿ mákas b(ə)khóyroys (צפוני: mákas b(ə)khéyréys)

רַבִּי יְהוּדָה הָיָה נוֹתֵֿן בָּהֶם סִמָּנִים: דְּצַ″ךְ, עַדַ″שׁ, בְּאַחַ″ב.

Standard: Reb [/rábi] Yehúdo hóyo nóyseyn bóhem simónim: dətsákh, adásh, b(ə)akáv.

Southern: Reb [/rábi] Yehí:du: hú:yu: nóysayn bú:hem simú:nim: dətsákh, adásh, b(ə)akáf.

Northern: Reb [/rábi] Yehúdo hóyo néyseyn bóhem simónim: dətsákh, adásh, b(ə)akáv.

◊

◊

חַד גַּדְיָא

- חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא, דִּזְבַּן [\דְּזַבִּין] אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא שׁוּנְרָא, וְאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא כַּלְבָּא, וְנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא חוּטְרָא, וְהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא נוּרָא, וְשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא מַיָּא, וְכָבָא לְנוּרָא, דְּשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא תּוּרָא, וְשָׁתָֿה לְמַיָּא, דְּכָבָא לְנוּרָא, דְּשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא שׁוֹחֵט, וְשָׁחַט לְתּוּרָא, דְּשָׁתָֿה לְמַיָּא, דְּכָבָא לְנוּרָא, דְּשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא מַלְאַךְ הַמָּוֶתֿ, וְשָׁחַט לְשׁוֹחֵט, דְּשָׁחַט לְתּוּרָא, דְּשָׁתָֿה לְמַיָּא, דְּכָבָא לְנוּרָא, דְּשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- וְאָתָֿא הַקָּדוֹשׁ בָּרוּךְ הוּא, וְשָׁחַט לְמַלְאָךְ הַמָּוֶתֿ, דְּשָׁחַט לְשׁוֹחֵט, דְּשָׁחַט לְתּוּרָא, דְּשָׁתָֿה לְמַיָּא, דְּכָבָא לְנוּרָא, דְּשָׂרַף לְחוּטְרָא, דְּהִכָּה לְכַּלְבָּא, דְּנָשַׁךְ לְשׁוּנְרָא, דְּאָכְלָא לְגַדְיָא, דִזְבַּן אַבָּא בִּתְֿרֵי זוּזֵי, חַד גַּדְיָא, חַד גַּדְיָא.

- חד גדיא: חד גדיא

Standard:

V(ə)óso hakódoysh bór(u)khu, vəshókhat ləmàlakh-hamóves, dəshókhat leshóykheyt — dəshókhat lətúro, dəshóso ləmáyo, dəkhóvo lənúro, dəsóraf ləkhútro, dəhíko ləkálbo, dənóshakh ləshúnro — dəókhlo ləgádyo, dízban [/dəzábin] ábo bisréy zúzey: khád gádyo, khad gádyo.

*

Southern:

V(ə)ú:su: hakúdoysh bú:r(u)khi:, vəshúkhat ləmàlakh-hamúves, dəshúkhat leshóykhayt — dəshúkhat lətí:ru:, dəshú:su: ləmáyu:, dəkhúvu ləní:ru:, dəsú:raf ləkhítru:, dəhí:ku: ləkálbu:, dənúshakh ləshínru: — dəókhlu: ləgádyu:, dízban [/dəzábin] ábu: bisráy zízay: khád gádyu:, khad gádyu:.

*

Northern:

V(ə)óso hakódeysh bór(u)khu, vəshókhat ləmàlakh-hamóves, dəshókhat leshéykheyt — dəshókhat lətúro, dəshóso ləmáyo, dəkhóvo lənúro, dəsóraf ləkhútro, dəhíko ləkálbo, dənóshakh ləshúnro — dəókhlo ləgádyo, dízban [/dəzábin] ábo bisréy zúzey: khád gádyo, khad gádyo.

◊

◊

In Modern European Hebrew Poetry

A Cultural, Literary and Linguistic Highpoint of Ashke-2

◊

◊

Chaim Nachman Bialik חיים נחמן בּיאַליק

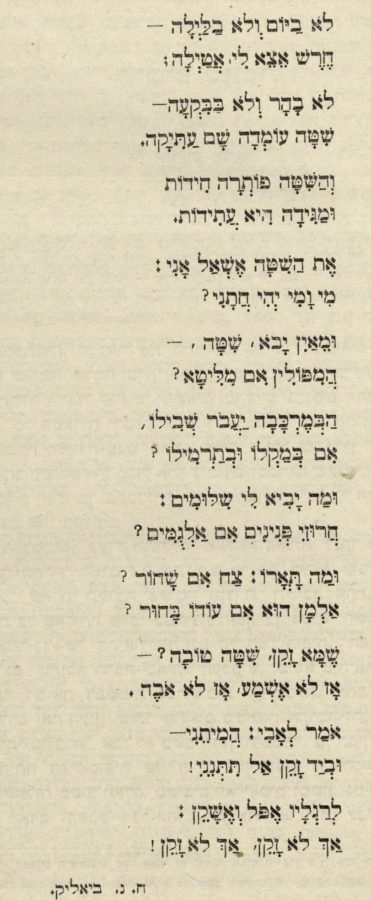

לֹא בַּיּוֹם וְלֹא בַּלַּיְלָה

◊

SUNG (2021) BY

JOANNA CZABAN | אַשקע טשאַבאַן

See also A. Z. Foreman’s reading of Bisəshuvósi and Al hashkhíto

Facsimile of the poem’s first publication in Ha-Shilóyakh (Hashiloah), Odessa 1908 (vol. 18, no. 2, p. 109). From the St. Petersburg National Library, with thanks to Julia Rets.

*

The vowel pointing of the following version generally follows the original, with some occasional deviation resulting from popular rendition.

- ◊

- לֹא בַּיּוֹם וְלֹא בַּלַּיְלָה Lóy bayóym v’loy baláylo

- חֶרֶשׁ אֵצֵא לִי אֲטַיְּלָה khéresh éytsey li atáylo

- לֹא בָּהָר וְלֹא בַּבִּקְעָה Lóy bohór v’loy babíko

- שִׁטָּה עָמְדָה שָׁם עַתִּיקָה shíto ómdo shom atíko

- ❋

- וְהַשִּׁטָּה פּוֹתְֿרָה חִידוֹתֿ V’hashíto póysro khídoys

- וּמַגִּידָה הִיא עֲתִֿידוֹתֿ umagído hi asídoys.

- אֶתֿ הַשִּׁטָּה אֶשְׁאַל אָנִי Es hashíto éshal óni

- מִי וָמִי יְהֵי חֲתָֿנִי Mí-vomí yəhéy khasóni

- ❋

- וּמֵאַיִן יָבֹא, שִׁטָּה Umèy-áyin yóvoy, shíto

- הֲמִפּוֹלִין אִם מִלִּיטָא ha-mi-Póyln im mi-Líto

- הֲבְמֶרְכָּבָה יַעֲבֹר שְׁבִילוֹ Ha-v’merkóvo yáyvoyr shvíloy

- אִם בְּמַקְלוֹ וּבְתַּרְמִילוֹ im bəmákloy uf-tarmíloy

- ❋

- וּמַה יָּבִיא לִי שִׁלּוּמִים Umá yóvi li shilúmim

- חֲרוּזֵי פְּנִינִים אִם אַלְגֻּמִּים Khrùzey-pnínim im algúmim

- וּמַה תָּאֳרוֹ — צַח אִם שָׁחוֹר Umá-tó-oroy, tsakh im shókhoyr

- אַלְמָן הוּא אִם עוֹדוֹ בָּחוּר álmon hú im óydoy bókhur

- ❋

- שֶׁמָא זָקֵן, שִׁטָּה טוֹבָה Shémo-zókeyn, shíto tóyvo

- אָז לֹא אֶשְׁמַע, אָז לֹא אֹבֶה oz lóy éshma, oz loy óyve

- אֹמַר לְאָבִי: הֲמִיתֵֿנִי !Òymar-l’óvi: Hamiséyni

- וּבְיַד זָקֵן אַל תִּתְּנֵנִי !uvyàd-zókeyn al titnéyni

- ❋

- לְרַגְלָיו אֶפֹּל וְאֶשָּׁקֵן L’ráglov-époyl v’eshókeyn

- אַךְ לֹא זָקֵן, אַךְ לֹא זָקֵן Akh lóy zókeyn, akh lóy zókeyn

◊

- In Warsaw Ashkenazic Hebrew:

- *

- Loy bayóym vəloy baláylu,

- khèyresh-áytsay li atáylu:

- Loy buhór vəloy babíku,

- shítu ómdu shom atíku.

- ❊

- Vəhashítu póysru khídoys,

- umagídu hi asídoys —

- Es hashítu éshal úni:

- Mì-vumí yəháy khasúni?

- ❊

- Imày-á:(y)in yúvoy, shítu?

- ha-mì-Póylin im mi-Lítu?

- Ha-vəmerkúvú yáavoyr shvíloy,

- im bəmákloy if-tarmíloy?

- ❊

- Imà-yúvi li shilímim?

- Khrìzay-pnínim im algímim?

- Imà-tú-uroy, tsakh im shúkhoyr?

- àlmon-hí im óydoy búkhir?

- ❊

- Shèymo-zúkayn, shítu tóyvu,

- oz lòy-éshma, oz loy óyve.

- Òymar-l’úvi: Hamisáyni —

- uvyàd-zúkayn al titnáyni!

- ❊

- Ləráglov époyl və-eshúkayn:

- Akh loy zúkayn, akh loy zúkayn.

◊

◊

- In Vilna Ashkenazic Hebrew

- ◊

- Ley bayéym vəley baláylo,

- khèresh-éytsey li atáylo:

- Ley bohór vəley babíko,

- shíto ómdo shom atíko.

- ❊

- Vəhashíto péysro khídeys,

- umagído hi asídeys —

- Es hashíto éshal óni:

- Mì-vomí yəhéy khasóni?

- ❊

- Umèy-áyin yóvey, shíto?

- ha-mì-Péylin im mi-Líto?

- Ha-vəmerkóvo yáaveyr shvíley,

- im bəmákley uf-tarmíley?

- ❊

- Umà-yóvi li shilúmim?

- Khrùzey-pnínim im algúmim?

- Umà-tó-orey, tsakh im shókheyr?

- àlmon-hú im óydey bókhur?

- ❊

- Shèmo-zókeyn, shíto téyvo,

- oz lèy-éshma, oz ley éyve.

- Èymar-l’óvi: Hamiséyni —

- uvyàd-zókeyn al titnéyni!

- ❊

- Ləráglov épeyl və-eshókeyn:

- Akh ley zókeyn, akh ley zókeyn

◊

◊

◊

ASHKENAZIC VARIABILITY

(FOR DIFFERENT KINDS OF PLEASURE: RHYME, RHYTHM, DIALECT, VERNACULAR INTIMACY, ETC):

Rhythm +/via Vernacularization / toward or away from Yiddishization…

Ha-vəmerkóvo [/hav-merkóvo] yáavoyr [N: yáyvoyr/yáyveyr/yáyvər; S: yá:voyr/yá:vər] shvíloy, הֲבְמֶרְכָּבָה יַעֲבֹר שְׁבִילוֹ

im bəmákloy uf-tarmíloy? [/uvə-sarmíylo] אִם בְּמַקְלוֹ וּבְתַּרְמִילוֹ

❋

◊

Rhyme + Vernacularization…

Umà-tó-oroy, tsakh im shókhoyr [/shókhər]? וּמַה תָּאֳרוֹ — צַח אִם שָׁחוֹר

àlmon-hú im óydoy bókhur [/bókhər]? אַלְמָן הוּא אִם עוֹדוֹ בָּחוּר

❋

◊

Vernacularization (=Yiddishization) alone…

Ləràglov-époyl və-eshókeyn [/N: eshókn / S: eshúkn] לְרַגְלָיו אֶפֹּל וְאֶשָּׁקֵן

Akh loy zókeyn, akh loy zókeyn [/N: zókn / S: zúkn] אַךְ לֹא זָקֵן, אַךְ לֹא זָקֵן

See also Bialik’s Yiddish version of the poem (use handles to turn pages):

Nit batog un nit banakht BIALIK

◊

◊

Ashkenazic Pleasure-Principle Variability

לפי הניב BY DIALECT

המיתני: hamisáyni ← hamiséyni (לכיוון דרומי, פּולין)

חידות: khídeys ← khídoys (לכיוון צפוני, ליטא)

לפי הקצב או המשקל BY RHYTHM AND SYLLABLIC STRUCTURE

הַבְמֶרְכָּבָה — havmerkóvo ∼ havəmerkóvo

לְפיִ הַלָּשׁוֹן הְַּיהוּדִיתֿ (אידיש) BY YIDISHIZATION / VERNACULARIZATION

To perfect the rhythm

יעבור — yáavoyr

או ל: yá:vər \ yá:voyr (לכיוון דרומי, פּולין)

או ל-:

yáyvər \ yáyvoyr (לכיוון צפוני, ליטא)

◊

To repair defective rhyme

Umà-tó-oroy, tsakh im shókhər?

àlmon-hú im óydoy bókhər?

בדרום:

(Umà-tó-oroy, tsakh im shúkhə(r

(àlmon-hú im óydoy búkhə(r

◊

◊

◊

Chaim Nachman Bialik’s Beír haharéygo

NOTE: In her Songs in Dark Times (Harvard University Press, 2020), Professor Amelia Glaser breaks the mold of arbitrarily recasting Ashkenazic poetry in an anachronous and inaccurate contemporary Israeli mold; see p. 54 etc.

בְּעִיר הַהֲרֵגָה

קוּם לֵךְ לְךָ אֶל עִיר הַהֲרֵגָה וּבָאתָֿ אֶל-הַחֲצֵרוֹתֿ, Kum léykh ləkhò, el ìr ha-haréygo uvóso el-hakhatséyroys

וּבְעֵינֶיךָ תִּרְאֶה וּבְיָדְךָ תְּמַשֵּׁשׁ עַל-הַגְּדֵרוֹתֿ Uvəeynèkho tíre, uvyòdkho təmásheysh al-hagdéyroys

וְעַל הָעֵצִים וְעַל הָאֲבָנִים וְעַל-גַּבֵּי טִיחַ הַכְּתָֿלִים Vəal ho-éytsim, vəal-hoavónim, vəal-gàbey tìakh-haksólim

אֶתֿ-הַדָּם הַקָּרוּשׁ וְאֶתֿ-הַמֹּחַ הַנִּקְשֶׁה שֶׁל-הַחֲלָלִים. Es hadòm-hakórush, vəes hamòyakh-haníkshe shèl hakhalólim

וּבָאתָֿ מִשָּׁם אֶל-הֶחֳרָבוֹתֿ וּפָסַחְתָּ עַל-הַפְּרָצִים

וְעָבַרְתָּ עַל-הַכְּתָֿלִים הַנְּקוּבִים וְעַל הַתַּנּוּרִים הַנִּתָּצִים,

בִּמְקוֹם הֶעֱמִיק קִרְקַר הַמַּפָּץ, הִרְחִיב הִגְדִּיל הַחוֹרִים,

מַחֲשֹף הָאֶבֶן הַשְּׁחֹרָה וְעָרוֹתֿ הַלְּבֵנָה הַשְּׂרוּפָה,

וְהֵם נִרְאִים כְּפֵיוֹתֿ פְּתוּחִים שֶׁל-פְּצָעִים אֲנוּשִׁים וּשְׁחֹרִים

אֲשֶׁר אֵין לָהֶם תַּקָּנָה עוֹד וְלֹא-תְֿהִי לָהֶם תְּרוּפָה,

וְטָבְעוּ רַגְלֶיךָ בְּנוֹצוֹתֿ וְהִתְנַגְּפוּ עַל תִּלֵּי-תִלִּים

שֶׁל-שִׁבְרֵי שְׁבָרִים וּרְסִיסֵי רְסִיסִים וּתְבוּסַתֿ סְפָרִים וּגְוִילִים,

כִּלְיוֹן עֲמַל לֹא-אֱנוֹשׁ וּפְרִי מִשְׁנֶה עֲבוֹדַתֿ פָּרֶךְ;

וְלֹא-תַֿעֲמֹד עַל-הַהֶרֶס וְעָבַרְתָּ מִשָּׁם הַדָּרֶךְ –

וְלִבְלְבוּ הַשִּׁטִּים לְנֶגְדְּךָ וְזָלְפוּ בְאַפְּךָ בְּשָׂמִים,

וְצִיצֵיהֶן חֶצְיָם נוֹצוֹתֿ וְרֵיחָן כְּרֵיחַ דָּמִים;

וְעַל-אַפְּךָ וְעַל-חֲמָתְֿךָ תָּבִיא קְטָרְתָּן הַזָּרָה

אֶתֿ-עֶדְנַתֿ הָאָבִיב בִּלְבָבְךָ – וְלֹא-תְֿהִי לְךָ לְזָרָא;

וּבְרִבֲבוֹתֿ חִצֵּי זָהָב יְפַלַּח הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ כְּבֵדְךָ

וְשֶׁבַע קַרְנַיִם מִכָּל-רְסִיס זְכוּכִיתֿ תִּשְׂמַחְנָה לְאֵידְךָ,

כִּי-קָרָא אֲדֹנָי לָאָבִיב וְלַטֶּבַח גַּם-יָחַד:

הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ זָרְחָה, הַשִּׁטָּה פָּרְחָה וְהַשּׁוֹחֵט שָׁחַט.

וּבָרָחְתָּ וּבָאתָֿ אֶל-חָצֵר, וְהֶחָצֵר גַּל בּוֹ –

Uvorákhto uvóso el-khótseyr, vəhekhótser gál bòy—

עַל הַגַּל הַזֶּה נֶעֶרְפוּ שְׁנַיִם: יְהוּדִי וְכַלְבּוֹ.

Al hagál hazè nérfu shnáyim: Yehúdi vekhál-bòy

קַרְדֹּם אֶחָד עֲרָפָם וְאֶל-אַשְׁפָּה אַחַתֿ הוּטָלוּ Kàrdoym ékhod arófom vəel-àshpo-ákhas hutólù

וּבְעֵרֶב דָּם שְׁנֵיהֶם יְחַטְטוּ חֲזִירִים וְיִתְֿגּוֹלָלוּ; Uvèyrev dàm-shnéyhem yəkhàtu khazèyrim vəyisgoylólù

מָחָר יֵרֵד גֶּשֶׁם וּסְחָפוֹ אֶל-אַחַד נַחֲלֵי הַבָּתֿוֹתֿ –

וְלֹא-יִצְעַק עוֹד הַדָּם מִן הַשְּׁפָכִים וְהָאַשְׁפָּתֿוֹתֿ,

כִּי בִּתְֿהֹם רַבָּה יֹאבַד אוֹ-יַשְׁקְ נַעֲצוּץ לִרְוָיָה –

וְהַכֹּל יִהְיֶה כְּאָיִן, וְהַכֹּל יָשׁוּב כְּלֹא-הָיָה.

וְאֶל עֲלִיּוֹתֿ הַגַּגֹּותֿ תְּטַפֵּס וְנִצַּבְתְּ שָׁם בָּעֲלָטָה –

עוֹד אֵימַתֿ מַר הַמָּוֶתֿ בַּמַּאֲפֵל הַדּוֹמֵם שָׁטָה;

וּמִכָּל-הַחוֹרִים הָעֲמוּמִים וּמִתּוֹךְ צִלְלֵי הַזָּוִיּוֹתֿ

עֵינַיִם, רְאֵה, עֵינַיִם דּוּמָם אֵלֶיךָ צוֹפִיּוֹתֿ.

רוּחוֹת הַ„קְּדוֹשִׁים“ הֵן, נְשָׁמוֹתֿ עוֹטְיוֹתֿ וְשׁוֹמֵמוֹתֿ,

אֶל-זָוִיתֿ אַחַתֿ תַּחַת כִּפַּתֿ הַגַּג הִצְטַמְצְמוּ – וְדוֹמֵמוֹתֿ.

כַּאן מְצָאָן הַקַּרְדֹּם וְאֶל-הַמָּקוֹם הַזֶּה תָּבֹאנָה

לַחְתֹּם פֹּה בְּמֶבָּטֵי עֵינֵיהֶן בַּפַּעַם הָאַחֲרוֹנָה

אֶתֿ כָּל-צַעַר מוֹתָֿן הַתָּפֵל וְאֶתֿ כָּל-תַּאֲלַתֿ חַיֵּיהֶן,

וְהִתְֿרַפְּקוּ פֹּה זָעוֹתֿ וַחֲרֵדוֹתֿ, וְיַחְדָּו מִמַּחֲבוֹאֵיהֶן

דּוּמָם תּוֹבְעוֹתֿ עֶלְבּוֹנָן וְעֵינֵיהֶן שׁוֹאֲלוֹת: לָמָּה? –

וּמִי-עוֹד כֵּאלֹהִים בָּאָרֶץ אֲשֶׁר-יִשָּׂא זֹאתֿ הַדְּמָמָה?

וְנָשָׂאתָֿ עֵינֶיךָ הַגָּגָה – וְהִנֵּה גַם רְעָפָיו מַחֲרִישִׁים,

מַאֲפִילִים עָלֶיךָ וְשׁוֹתְֿקִים, וְשָׁאַלְתָּ אֶתֿ-פִּי הָעַכָּבִישִׁים;

עֵדִים חַיִּים הֵם, עֵדֵי רְאִיָּה, וְהִגִּידוּ לְךָ כָּל-הַמּוֹצְאוֹתֿ:

מַעֲשֶׂה בְּבֶטֶן רֻטָּשָה שֶׁמִּלּאוּהָ נוֹצוֹתֿ,

מַעֲשֶׂה בִּנְחִירַיִם וּמַסְמֵרוֹתֿ, בְּגֻלְגָּלוֹתֿ וּפַטִּישִׁים,

מַעֲשֶׂה בִּבְנֵי אָדָם שְׁחוּטִים שֶׁנִּתְֿלוּ בְּמָרִישִׁים,

וּמַעֲשֶׂה בְּתִּינוֹק שֶׁנִּמְצָא בְּצַד אִמּוֹ הַמְדֻקָּרָה

כְּשֶׁהוּא יָשֵׁן וּבְפִיו פִּטְמַתֿ שָׁדָהּ הַקָּרָה;

וּמַעֲשֶׂה בְּיֶלֶד שֶׁנִּקְרַע וְיָצְאָה נִשְׁמָתוֹ בְּ„אִמִּי!“ –

וְהִנֵּה גַם עֵינָיו פֹּה שׁוֹאֲלוֹת חֶשְׁבּוֹן מֵעִמִּי.

וְעוֹד כָּאֵלֶּה וְכָאֵלֶּה תְּסַפֵּר לְךָ הַשְׂמָמִיתֿ

מַעֲשִׂים נוֹקְבִים אֶתֿ-הַמֹּחַ וְיֵשׁ בָּהֶם כְּדֵי לְהָמִיתֿ

אֶתֿ-רוּחֲךָ וְאֶתֿ-נִשְׁמָתְֿךָ מִיתָֿה גְּמוּרָה עוֹלָמִיתֿ –

וְהִתְאַפַּקְתָּ, וְחָנַקְתָּ בְּתֿוֹךְ גְּרוֹנְךָ אֶתֿ הַשְּׁאָגָה

וּקְבַרְתָהּ בְּמַעֲמַקֵּי לְבָבְךָ לִפְנֵי הִתְֿפָּרְצָהּ,

וְקָפַצְתָּ מִשָּׁם וְיָצָאתָֿ – וְהִנֵּה הָאָרֶץ כְּמִנְהָגָהּ,

וְהַשֶּׁמֶשׁ כִּתְֿמֹל שִׁלְשֹׁם תְּשַׁחֵתֿ זָהֳרָהּ אָרְצָה.

וְיָרַדְתָּ מִשָּׁם וּבָאתָֿ אֶל-תּוֹךְ הַמַּרְתֵּפִים הָאֲפֵלִים,

מְקוֹם נִטְמְאוּ בְּנוֹתֿ עַמְּךָ הַכְּשֵׁרוֹתֿ בֵּין הַכֵּלִים,

אִשָּׁה אִשָּׁה אַחַתֿ תַּחַתֿ שִׁבְעָה שִׁבְעָה עֲרֵלִים,

הַבַּתֿ לְעֵינֵי אִמָּהּ וְהָאֵם לְעֵינֵי בִּתָּהּ,

לִפְנֵי שְׁחִיטָה וּבִשְׁעַתֿ שְׁחִיטָה וּלְאַחַר שְׁחִיטָה;

וּבְיָדְךָ תְּמַשֵּׁש אֶתֿ-הַכֶּסֶתֿ הַמְטֻנֶּפֶתֿ וְאֶתֿ-הַכָּר הַמְאָדָּם,

מִרְבַּץ חֲזִירֵי יַעַר וּמִרְבַּעַתֿ סוּסֵי אָדָם

עִם-קַרְדֹּם מְטַפְטֵף דָּם רוֹתֵֿחַ בְּיָדָם.

וּרְאֵה גַּם-רְאֵה: בַּאֲפֵלַתֿ אוֹתָֿהּ זָוִיתֿ,

תַּחַתֿ מְדוֹכַתֿ מַצָּה זוֹ וּמֵאֲחוֹרֵי אוֹתָֿהּ חָבִיתֿ,

שָׁכְבוּ בְעָלִים, חֲתָֿנִים, אַחִים, הֵצִיצוּ מִן-הַחוֹרִים

בְּפַרְפֵּר גְּוִיּוֹתֿ קְדוֹשׁוֹתֿ תַּחַת בְּשַׂר חֲמוֹרִים,

נֶחֱנָקוֹתֿ בְּטֻמְאָתָֿן וּמְעַלְּעוֹתֿ דַּם צַוָּארָן,

וּכְחַלֵּק אִישׁ פַּתֿ-בָּגוֹ חִלֵּק מְתֹֿעָב גּוֹי בְּשָׂרָן –

שָׁכְבוּ בְּבָשְׁתָּן וַיִּרְאוּ – וְלֹא נָעוּ וְלֹא זָעוּ,

וְאֶתֿ-עֵינֵיהֶם לֹא-נִקֵּרוּ וּמִדַּעְתָּם לֹא יָצָאוּ –

וְאוּלַי גַּם-אִישׁ לְנַפְשׁוֹ אָז הִתְֿפַּלֵּל בִּלְבָבוֹ:

רִבּוֹנוֹ שֶׁל-עוֹלָם, עֲשֵׂה נֵס – וְאֵלַי הָרָעָה לֹא-תָבֹֿא.

וְאֵלֶּה אֲשֶׁר חָיוּ מִטֻּמְאָתָֿן וְהֵקִיצוּ מִדָּמָן –

וְהִנֵּה שֻׁקְּצוּ כָּל-חַיֵּיהֶן וְנִטְמָא אוֹר עוֹלָמָן

שִׁקּוּצֵי עוֹלָם, טֻמְאַתֿ גּוּף וָנֶפֶשׁ, מִבַּחוּץ וּמִבִּפְנִים –

וְהֵגִיחוּ בַעֲלֵיהֶן מֵחוֹרָם וְרָצוּ בֵּיתֿ-אֱלֹהִים

וּבֵרְכוּ עַל-הַנִּסִּים שֵׁם אֵל יִשְׁעָם וּמִשְׂגַּבָּם;

וְהַכֹּהֲנִים שֶׁבָּהֶם יֵצְאוּ וְיִשְׁאֲלוּ אֶתֿ רַבָּם:

“רַבִּי! אִשְׁתִּי מָה הִיא? מֻתֶּרֶתֿ אוֹ אֲסוּרָה?” –

וְהַכֹּל יָשׁוּב לְמִנְהָגוֹ, וְהַכֹּל יַחֲזֹר לְשׁוּרָה.

וְעַתָּה לֵךְ וְהֵבֵאתִֿיךָ אֶל-כָּל הַמַּחֲבוֹאִים:

בָּתֵּי מָחֳרָאוֹתֿ, מִכְלְאוֹתֿ חֲזִירִים וּשְׁאָר מְקוֹמוֹתֿ צוֹאִים.

וְרָאִיתָֿ בְּעֵינֶיךָ אֵיפֹה הָיוּ מִתְחַבְּאִים

אַחֶיךָ, בְּנֵי עַמֶּךָ וּבְנֵי בְנֵיהֶם שֶׁל-הַמַּכַּבִּים,

נִינֵי הָאֲרָיוֹתֿ שֶׁבְּ„אַב הָרַחֲמִים“ וְזֶרַע הַ„קְּדוֹשִׁים“.

עֶשְׂרִים נֶפֶשׁ בְּחוֹר אֶחָד וּשְׁלֹשִׁים שְׁלֹשִׁים,

וַיְגַדְּלוּ כְבוֹדִי בָּעוֹלָם וַיְקַדְּשׁוּ שְׁמִי בָּרַבִּים…

מְנוּסַתֿ עַכְבָּרִים נָסוּ וּמַחֲבֵא פִשְׁפְּשִׁים הָחְבָּאוּ,

וַיָמוּתֿוּ מוֹתֿ כְּלָבִים שָׁם בַּאֲשֶׁר נִמְצָאוּ,

וּמָחָר לַבֹּקֶר – וְיָצָא הַבֵּן הַפָּלִיט

וּמָצָא שָׁם פֶּגֶר אָבִיו מְגֹאָל וְנִמְאָס – – –

וְלָמָּה תֵּבְךְּ, בֶּן-אָדָם, וְלָמָּה תָּלִיט

אֶתֿ-פָּנֶיךָ בְּכַפְּךָ? – חֲרֹק שִׁנַּיִם וְהִמָּס!

וְיָרַדְתָּ בְּמוֹרַד הָעִיר וּמָצָאתָֿ גִּנַּתֿ יָרָק,

וַאֲוֵרָה גְדוֹלָה עִם הַגִּנָּה, הִיא אֲוֵרַתֿ הֶהָרֶג.

וּכְמַחֲנֵה תִּנְשְׁמוֹתֿ עֲנָק וְאֵימֵי עֲטַלֵּפִים

הַסְּרוּחִים עַל-חַלְלֵיהֶם שִׁכּוֹרֵי דָם וַעֲיֵפִים.

שָׁם עַל קַרְקַע הָאֲוֵרָה שָׁטְחוּ לָהֶם שֶׁטַח

אוֹפַנִּים מְפֻשְּׂקֵי יְתֵֿדוֹתֿ כְּאֶצְבָּעוֹתֿ שְׁלוּחוֹתֿ לִרְצֹחַ,

וּפִיפִיּוֹתָם מְגֹאָלִים עוֹד בְּדַם אָדָם וָמֹחַ.

וְהָיָה בַּעֲרֹב הַיּוֹם, בִּנְטוֹת שֶׁמֶשׁ מַעֲרָבָה,

מְעֻטָּף בְּעַנְנֵי דָּם וְנֶאְפַּד אֵשׁ לֶהָבָה,

וּפָתַֿחְתָּ אֶתֿ-הַשַּׁעַר, בַּלָּט וּבָאתָֿ אֶל-הָאֲוֵרָה

וְאֵימָה חֲשֵׁכָה תִּבְלָעֶךָּ, וּתְֿהֹם זְוָעָה נַעֲלָמָה:

מָגוֹר, מָגוֹר מִסָּבִיב… מְשׁוֹטֵט הוּא בַּאֲוֵרָהּ,

שׁוֹרֶה הוּא עַל הַכְּתָֿלִים וְכָבוּשׁ בְּתֿוֹךְ הַדְּמָמָה.

וּמִתַּחַתֿ תִּלֵּי הָאוֹפַנִּים, מִבֵּין הַחוֹרִים וְהַסְּדָקִים,

עוֹר תַּרְגִּישׁ כְּעֵין פִּרְפּוּר שֶׁל-אֲבָרִים מְרֻסָּקִים,

מְזִיזִים אֶתֿ הָאוֹפַנִּיםֿ הַתְּלוּלִים עַל-גַּבֵּיהֶם,

מִתְעַוְּתִֿים בִּגְסִיסָתָֿם וּמִתְֿבּוֹסְסִים בִּדְמֵיהֶם;

וְאֶנְקַתֿ חֲשָׁאִים אַחֲרוֹנָה – קוֹל עֲנוֹתֿ חֲלוּשָׁה

מִמַּעַל לְרֹאשְׁךָ עֲדַיִן תְּלוּיָה כְּמוֹ קְרוּשָׁה,

וּכְעֵין צַעַר נֶעְכָּר, צַעַר עוֹלָם, תּוֹסֵס שָׁם וְחָרֵד.

אֵין זֹאתֿ כִּי אִם-רוּחַ דַּכָּא רַב-עֱנוּת וּגְדֹל-יִסּוּרִים

חָבַשׁ כָּאן אֶתֿ-עַצְמוֹ בְּתֿוֹךְ בֵּיתֿ הָאֲסוּרִים,

נִתְֿקַע פֹּה בִּדְוֵי עוֹלָם וְלֹא-יֹאבֶה עוֹד הִפָּרֵד,

וּשְׁכִינָה שְׁחֹרָה אַחַתֿ, עֲיֵפַתֿ צַעַר וִיגֵעַת כֹּחַ,

מִתְלַבֶּטֶתֿ פֹּה בְּכָל-זָוִיתֿ וְלֹא-תִמְצָא לָהּ מָנוֹחַ,

רוֹצָה לִבְכּוֹת – וְאֵינָהּ יְכוֹלָה, חֲפֵצָה לִנְהֹם – וְשׁוֹתֶֿקֶתֿ,

וְדוּמָם תִּמַּק בְּאֶבְלָהּ וּבַחֲשָׁאִי הִיא נֶחֱנֶקֶתֿ,

פּוֹרֶשֶׂתֿ כְּנָפֶיהָ עַל צִלְלֵי הַקְּדוֹשִׁים וְרֹאשָׁהּ תַּחַתֿ כְּנָפָהּ,

מַאֲפִילָה עַל-דִּמְעוֹתֶֿיהָ וּבוֹכִיָּה בְלִי שָׂפָה – – –

וְאַתָּה גַם-אַתָּה, בֶּן-אָדָם, סְגֹר בַּעַדְךָ הַשַּׁעַר,

וְנִסְגַּרְתָּ פֹּה בָּאֲפֵלָה וּבַקַּרְקַע תִּכְבֹּשׁ עֵינֶיךָ

וְנִצַּבְתָּ כֹּה עַד-בּוֹשׁ וְהִתְֿיַחַדְתָּ עִם-הַצַּעַר

וּמִלֵּאתָֿ בּוֹ אֶתֿ-לְבָבְךָ לְכֹל יְמֵי חַיֶּיךָ,

וּבְיוֹם תְּרֻשַּׁשׁ נַפְשְּךָ וּבַאֲבֹד כָּל חֵילָהּ –

וְהָיָה הוּא לְךָ לִפְלֵיטָה וּלְמַעְיַן תַּרְעֵלָה,

וְרָבַץ בְּךָ כִּמְאֵרָה וִיבַעֶתְֿךָ כְּרוּחַ רָעָה,

וּלְפָֿתְךָ וְהֵעִיק עָלֶיךָ כְּהָעֵק חֲלוֹם זְוָעָה;

וּבְחֵיקְךָ תִּשָּׂאֶנּוּ אֶל-אַרְבַּע רוּחוֹתֿ הַשָּׁמַיִם,

וּבִקַּשְׁתָּ וְלֹא-תִֿמְצָא לוֹ נִיב שְׂפָתַֿיִם.

וְאֶל-מִחוּץ לָעִיר תֵּצֵא וּבָאתָֿ אֶל בֵּיתֿ-הָעוֹלָם,

וְאַל-יִרְאֲךָ אִישׁ בְּלֶכְתְּךָ וִיחִידִי תָּבֹא שָׁמָּה,

וּפָקַדְתָּ קִבְרוֹתֿ הַקְּדוֹשִׁים לְמִקְּטַנָּם וְעַד-גְּדוֹלָם,

וְנִצַּבְתָּ עַל עֲפָרָם הַתָּחוּחַ וְהִשְׁלַטְתִּי עָלֶיךָ דְּמָמָה:

וּלְבָבְךָ יִמַּק בְּךָ מֵעֹצֶר כְּאֵב וּכְלִמָּה –

וְעָצַרְתִּי אֶתֿ-עֵינֶיךָ וְלֹא-תִֿהְיֶה דִמְעָה,

וְיָדַעְתָּ כִּי עֵתֿ לִגְעוֹתֿ הִיא כְּשׁוֹר עָקוּד עַל הַמַּעֲרָכָה –

וְהִקְשַׁחְתִּי אֶת-לְבָבְךָ וְלֹא-תָֿבֹא אֲנָחָה.

הִנֵּה הֵם עֶגְלִֵי הַטִּבְחָה, הִנֵּה הֵם שׁוֹכְבִים כֻּלָּם –

וְאִם יֵשׁ שִׁלּוּמִים לְמוֹתָֿם – אֱמֹר, בַּמֶּה יְשֻׁלָּם?

סִלְחוּ לִי, עֲלוּבֵי עוֹלָם, אֱלֹהֵיכֶם עָנִי כְמוֹתְֿכֶם,

עָנִי הוּא בְחַיֵּיכֶם וְקַל וָחֹמֶר בְּמוֹתְֿכֶם,

כִּי תָֿבֹאוּ מָחָר עַל-שְׂכַרְכֶם וּדְפַקְתֶּם עַל-דְּלָתָֿי –

אֶפְתְּחָה לָכֶם, בֹּאוּ וּרְאוּ: יָרַדְתִּי מִנְּכָסָי!

וְצַר לִי עֲלֵיכֶם, בָּנַי, וְלִבִּי לִבִּי עֲלֵיכֶם:

חַלְלֵיכֶם – חַלְלֵי חִנָּם, וְגַם-אֲנִי וְגַם-אַתֶּם

לֹא-יָדַעְנוּ לָמָּה מַתֶּם וְעַל-מִי וְעַל-מָה מַתֶּם,

וְאֵין טַעַם לְמוֹתְֿכֶם כְּמוֹ אֵין טַעַם לְחַיֵּיכֶם.

וּשְׁכִינָה מָה אוֹמֶרֶתֿ? – הִיא תִּכְבֹּש בֶּעָנָן אֶתֿ רֹאשָׁהּ

וּמֵעֹצֶר כְּאֵב וּכְלִמָּה פּוֹרֶשֶׁתֿ וּבוֹכָה…

וְגַם-אֲנִי בַּלַּיְלָה בַלַּיְלָה אֵרֵד עַל הַקְּבָרִים,

אֶעֱמֹד אַבִּיט אֶל-הַחֲלָלִים וְאֵבוֹשׁ בַּמִּסְתָּרִים –

וְאוּלָם, חַי אָנִי, נְאוּם יְיָ, אִם-אוֹרִיד דִּמְעָה.

וְגָדוֹל הַכְּאֵב מְאֹד וּגְדוֹלָה מְאֹד הַכְּלִמָּה –

וּמַה-מִּשְּׁנֵיהֶם גָּדוֹל? – אֱמֹר אַתָּה, בֶּן אָדָם!

אוֹ טוֹב מִזֶּה – שְׁתֹק! וְדוּמָם הֱיֵה עֵדִי,

כִּי-מְצָאתַנִי בִקְלוֹנִי וַתִּרְאֵנִי בְּיוֹם אֵידִי;

וּכְשׁוּבְךָ אֶל-בְּנֵי עַמֶּךָ – אַל-תָּשׁוּב אֲלֵיהֶם רֵיקָם,

כִּי מוּסַר כְּלִמָּתִי תִּשָּׂא וְהוֹרַדְתּוֹ עַל-קָדְקֳדָם,

וּמִכְּאֵבִי תִּקַּח עִמְּךָ וַהֲשֵׁבוֹתוֹ אֶל-חֵיקָם.

וּפָנִיתָ לָלֶכֶת מֵעִם קִבְרוֹת הַמֵּתִים, וְעִכְּבָה

רֶגַע אֶחָד אֶתֿ-עֵינֶיךָ רְפִידַת הַדֶּשֶׁא מִסָּבִיב,

וְהַדֶּשֶׁא רַךְ וְרָטֹב, כַּאֲשֶׁר יִהְיֶה בִּתְחִלַּתֿ הָאָבִיב:

נִצָּנֵי הַמָּוֶתֿ וַחֲצִיר קְבָרִים אַתָּה רוֹאֶה בְעֵינֶיךָ;

וְתָֿלַשְׁתָּ מֵהֶם מְלֹא הַכַּף וְהִשְׁלַכְתָּם לַאֲחוֹרֶיךָ,

לֵאמֹר: חָצִיר תָּלוּשׁ הָעָם – וְאִם-יֵשׁ לַתָּלוּשׁ תִּקְוָה?

וְעָצַמְתָּ אֶתֿ-עֵינֶיךָ מֵרְאוֹתָֿם, וּלְקַחְתִּיךָ וַאֲשִׁיבְךָ

מִבֵּיתֿ-הַקְּבָרוֹתֿ אֶל-אַחֶיךָ אֲשֶׁר חָיוּ מִן-הַטִּבְחָה,

וּבָאתָֿ עִמָּם בְּיוֹם צוּמָם אֶל בָּתֵּי תְפִלָּתָֿם

וְשָׁמַעְתָּ זַעֲקַתֿ שִׁבְרָם וְנִסְחַפְתָּ בְדִמְעָתָֿם;

וְהַבַּיִתֿ יִמָּלֵא יְלָלָה, בְּכִי וְנַאֲקַת פֶּרֶא,

וְסָמְרָה שַׂעֲרַתֿ בְּשָׂרְךָ וּפַחַד יִקְרָאֲךָ וּרְעָדָה –

כָּכָה תֶּאֱנֹק אֻמָּה אֲשֶׁר אָבְדָה אָבָדָה…

וְאֶל-לְבָבָם תַּבִּיט – וְהִנּוֹ מִדְבָּר וְצִיָּה,

וְכִי-תִצְמַח בּוֹ חֲמַת נָקָם – לֹא תְחַיֶּה זֶרַע,

וְאַף קְלָלָה נִמְרֶצֶת אַחַת לֹא-תוֹלִיד עַל-שִׂפְתֵיהֶם.

הַאֵין פִּצְעֵיהֶם נֶאֱמָנִים – – וְלָמָה תְפִלָּתָם רְמִיָּה?

לָמָּה יֱכַחֲשׁוּ לִי בְּיוֹם אֵידָם, וּמַה-בֶּצַע בְּכַחֲשֵׁיהֶם?

וּרְאֵה גַם-רְאֵה: עוֹד הֵם נְמַקִּים בִּיגוֹנָם,

כֻּלָּם יוֹרְדִים בַּבֶּכִי, יִשְּׂאוּ קִינָה בְּנִיהֶם,

וְהִנֵּה הֵם מְתוֹפְפִים עַל-לִבְבֵיהֶם וּמִתְוַדִּים עַל-עֲוֹנָם

לֵאמֹר: “אָשַׁמְנוּ בָּגַדְנוּ” – וְלִבָּם לֹא-יַאֲמִין לְפִיהֶם.

הֲיֶחֱטָא עֶצֶב נָפוֹץ וְאִם-שִׁבְרֵי חֶרֶשׂ יֶאְשָמוּ?

וְלָמָּה זֶה יִתְחַנְּנוּ אֵלָי? – דַּבֵּר אֲלֵיהֶם וְיִרְעָמוּ!

יָרִימוּ-נָא אֶגְרֹף כְּנֶגְדִי וְיִתְבְּעוּ אֶתֿ עֶלְבּוֹנָם,

אֶתֿ-עֶלְבּוֹן כָּל-הַדּוֹרוֹתֿ מֵרֹאשָׁם וְעַד-סוֹפָם,

וִיפוֹצְצוּ הַשָּׁמַיִם וְכִסְאִי בְּאֶגְרוֹפָם.

וְגַם-אַתָּה, בֶּן-אָדָם, אַל-תִּבָּדֵל מִתּוֹךְ עֲדָתָֿם,

הַאֲמֵן לְנִגְעֵי לִבָּם וְאַל-תַּאֲמֵן לִתְֿחִנָּתָֿם;

וּבְהָרֵם הַחַזָּן קוֹלוֹ: „עֲשֵׂה לְמַעַן הַטְּבוּחִים!

עֲשֵׂה לְמַעַן תִּינֹוקוֹתֿ! עֲשֵׂה לְמַעַן עוֹלְלֵי טִפּוּחִים“!

וְעַמּוּדֵי הַבַּיִתֿ יִתְפַּלְּצוּ בְּזַעֲקַתֿ תַּאֲנִיָּה,

וְסָמְרָה שַׂעֲרַתֿ בְּשָׂרְךָ וּפַחַד יִקְרָאֲךָ וּרְעָדָה –

וְהִתְאַכְזַרְתִּי אֲנִי אֵלֶיךָ – וְלֹא תִֿגְעֶה אִתָּם בִּבְכִיָּה

וְכִי תִּפְרֹץ שַׁאֲגָתְֿךָ – אֲנִי בֵּין שִׁנֶּיךָ אֲמִיתֶֿנָּה;

יְחַלְּלוֹּ לְבַדָּם צָרָתָֿם – וְאַתָּה אַל תְּחַלְּלֶנָּה.

תַּעֲמֹד הַצָּרָה לְדוֹרוֹתֿ – צָרָה לֹא-נִסְפָּדָה,

וְדִמְעָתְךָ אַתָּה תֵּאָצֵר דִּמְעָה בְלִי-שְׁפוּכָה,

וּבָנִיתָֿ עָלֶיהָ מִבְצַר בַּרְזֶל וְחוֹמַתֿ נְחוּשָׁה

שֶׁל-חֲמַתֿ מָוֶתֿ, שִׂנְאַתֿ שְׁאוֹל וּמַשְׂטֵמָה כְבוּשָׁה,

וְנֹאחֲזָה בִלְבָבְךָ וְגָדְלָה שָׁם כְּפֶתֶֿן בִּמְאוּרָתֿוֹ,

וִינַקְתֶּם זֶה מִזֶּה וְלֹא-תִמְצְאוּ מְנוּחָה;

וְהִרְעַבְתָּ וְהִצְמֵאתָֿ אוֹתֿוֹ – וְאַחַר תַּהֲרֹס חוֹמָתֿוֹ

וּבְרֹאשׁ פְּתָֿנִים אַכְזָר לַחָפְשִׁי תְשַׁלְּחֶנּוּ

וְעַל-עַם עֶבְרָתְֿךָ וְחֶמְלָתְֿךָ בְּיוֹם רַעַם תְּצַוֶּנּוּ.

עַתָּה צֵא מִזֶּה וְשׁוּב הֵנָּה בֵּין הַשְּׁמָשׁוֹתֿ

וְרָאִיתָֿ אַחֲרִיתֿ אֵבֶל עָם: וְהִנֵּה כָּל-אֵלֶּה הַנְּפָשׁוֹתֿ

אֲשֶׁר-חָרְדוּ וְהֵקִיצוּ בֹקֶר – שָׁבוּ לָעֶרֶב וַתֵּרָדַמְנָה,

ִויגֵעֵי בֶכִי וְדַכֵּי רוּחַ הִנָּם עוֹמְדִים עַתָּה בַּחֲשֵׁכָה,

עוֹד הַשְּׂפָתַֿיִם נָעוֹתֿ, מְפַלְּלוֹתֿ – אַךְ הַלֵּב נָחַר תּוֹכוֹ,

וּבְלֹא נִיצוֹץ תִּקְוָה בַּלֵּב וּבְלִי שְׁבִיב אוֹר בָּעָיִן

הַיָּד תְּגַשֵּׁשׁ בָּאֲפֵלָה, תְּבַקֵּשׁ מִשְׁעָן – וָאִָיִן…

כָּכָה תֶּעְשַׁן עוֹד הַפְּתִֿילָה אַחֲרֵי כְלוֹתֿ שַּמְנָהּ,

כָּךְ יִמְשֹׁךְ סוּס זָקֵן אֲשֶׁר נִשְׁבַּר כֹּחוֹ.

לוּ אַגָּדַת תַּנְחוּמִים אַחַת הִנִּיחָה לָהֶם צָרָתָֿם,

לִהְיוֹתֿ לָהֶם לִמְשִׁיבַתֿ נֶפֶשׁ וּלְכַלְכֵּל שֵׂיבָתָֿם!

הִנֵּה כָלָה הַצּוֹם, קָרְאוּ „וַיְחַל“, אָמְרוּ „עֲנֵנוּ“ – וְלָמָּה

עוֹד הַצִּבּוּר מִתְֿמַהְמֵהַּ? – הַיִקְרְאוּ גַּם „אֵיכָה? –

לֹא! הִנֵּה דַרְשָׁן עוֹלֶה עַל-הַבָּמָה,

הִנֵּה הוּא פוֹתֵֿחַ פִּיו, מְגַמְגֵּם וּמְפִיחַ אֲמָרָיו,

טָח תָּפֵל וְלוֹחֵשׁ פְּסוּקִים עַל מַכָּתָֿם הַטְּרִיָּה,

וְאַף קוֹל אֱלֹהִים אֶחָד לֹא-יַצִּיל מִפִּיהוּ,

גַּם-נִיצוֹץ קָטָן אֶחָד לֹא-יַדְלִיק בִּלְבָבָם;

וְעֵדֶר אֲדֹנָי עוֹמֵד בִּזְקֵנָיו וּבִנְעָרָיו,

אֵלֶּה שׁוֹמְעִים וּמְפַהֲקִים וְאֵלֶּה רֹאשׁ יָנִיעוּ;

תַּו הַמָּוֶתֿ עַל-מִצְחָם וּלְבָבָם יֻכַּתֿ שְׁאִיָּה.

מֵתֿ רוּחָם, נָס לֵחָם, וֵאלֹהֵיהֶם עֲזָבָם.

וְגַם אַתָּה אַל-תָּנֹד לָהֶם, אַל-תְּזַעְזַע חִנָּם פִּצְעֵיהֶם,

אַל-תִּגְדֹּשׁ עוֹד לַשָּׁוְא סְאַתֿ צָרָתָֿם הַגְּדוּשָׁה;

בַּאֲשֶׁר תִּגַּע אֶצְבָּעֲךָ – שָׁמָּה מַכָּה אֲנוּשָׁה,

כָּל-בְּשָׂרָם עֲלֵיהֶם יִכְאַב – אֲבָל נוֹשְׁנוּ בְּמַכְאוֹבֵיהֶם

וַיַּשְׁלִימוּ עִם חַיֵּי בָשְׁתָּם, וּמַה-בֶּצַע כִּי תְנַחֲמֵם?

עֲלוּבִים הֵם מִקְּצֹף עֲלֵיהֶם וְאוֹבְדִים הֵם מֵרַחֲמֵם;

הַנַּח לָהֶם וְיֵלֵכוּ – הִנֵּה יָצְאוּ הַכּוֹכָבִים,

וַאֲבֵלִים וַחֲפוּיֵי רֹאשׁ וּבְבֹשֶׁתֿ גַּנָּבִים

אִישׁ אִישׁ עִם-נִגְעֵי לִבּוֹ יָשׁוּב הַבָּיְתָֿה,

וְגֵווֹ כָּפוּף מִשֶּׁהָיָה וְנַפְשׁוֹ רֵיקָה מִשֶּׁהָיְתָה,

וְאִישׁ אִישׁ עִם נִגְעֵי לִבּוֹ יַעֲלֶה עַל-מִשְׁכָּבוֹ

וְהַחֲלֻדָּה עַל-עֲצָמָיו וְהָרָקָב בִּלְבָבוֹ…

וְהָיָה כִּי-תַשְׁכִּים מָחָר וְיָצָאתָֿ בְּרֹאשׁ דְּרָכִים –

וְרָאִיתָ הֲמוֹן שִׁבְרֵי אָדָם נֶאֱנָקִים וְנֶאֱנָחִים,

צוֹבְאִים עַל חַלּוֹנוֹת גְּבִירִים וְחוֹנִים עַל הַפְּתָחִים,

מַכְרִיזִים בְּפֻמְבֵּי עַל-פִּצְעֵיהֶם כְּרוֹכֵל עַל-מַרְכֹּלֶת,

לְמִי גֻּלְגֹּלֶת רְצוּצָה וּלְמִי פֶּצַע יָד וְחַבּוּרָה,

וְכֻלָּם פּוֹשְׁטִים יָד כֵּהָה וְחוֹשְׂפִים זְרוֹעַ שְׁבוּרָה,

וְעֵינֵיהֶם, עֵינֵי עֲבָדִים מֻכִּים, אֶל יַד גְּבִירֵיהֶם,

לֵאמֹר: “גֻּלְגֹּלֶת רְצוּצָה לִי, אָב “קָדוֹשׁ” לִי –תְּנָה אֶתֿ תַּשְׁלוֹמֵיהֶם!”

וּגְבִירִים בְּנֵי רַחֲמָנִים מִתְמַלְּאִים עֲלֵיהֶם רַחֲמִים

וּמוֹשִׁיטִים לָהֶם מִבִּפְנִים מַקֵּל וְתַֿרְמִיל לַגֻּלְגֹּלֶתֿ,

אוֹמְרִים „בָּרוּךְ שֶׁפְּטָרָנוּ“ – וְהַקַּבְּצָנִים מִתְֿנַחֲמִים.

לְבֵית הַקְּבָרוֹתֿ, קַבְּצָנִים! וַחֲפַרְתֶּם עַצְמוֹתֿ אֲבוֹתֵֿיכֶם

וְעַצְמוֹתֿ אַחֵיכֶם הַקְּדוֹשִׁים וּמִלֵּאתֶֿם תַּרְמִילֵיכֶם

וַעֲמַסְתֶּם אוֹתָֿם עַל-שֶׁכֶם וִיצָאתֶֿם לַדֶּרֶךְ, עֲתִֿידִים

לַעֲשׂוֹתֿ בָּהֶם סְחוֹרָה בְּכָל-הַיְרִידִים;

וּרְאִיתֶֿם לָכֶם יָד בְּרֹאשׁ דְּרָכִים, לְעֵין רוֹאִים,

וּשְׁטַחְתֶּם אוֹתָֿם לַשֶּׁמֶשׁ עַל-סְמַרְטוּטֵיכֶם הַצֹּאִים,

וּבְגָרוֹן נִחָר שִׁירָה קַבְּצָנִיתֿ עֲלֵיהֶם תְּשׁוֹרְרוּ,

וּקְרָאתֶֿם לְחֶסֶד לְאֻמִּים וְהִתְֿפַּלַּלְתֶּם לְרַחֲמֵי גוֹיִם,

וְכַאֲשֶׁר פְּשַׁטְתֶּם יָד תִּפְשֹׁטוּ, וְכַאֲשֶׁר שְׁנוֹרַרְתֶּם תִּשְׁנוֹרְרוּ.

וְעַתָּה מַה-לְךָ פֹּה, בֶּן-אָדָם, קוּם בְּרַח הַמִּדְבָּרָה

וְנָשָׂאתָֿ עִמְּךָ שָׁמָּה אֶתֿ-כּוֹס הַיְגוֹנִים,

וְקָרַעְתָּ שָׁם אֶתֿ-נַפְשְׁךָ לַעֲשָׂרָה קְרָעִים

וְאֶתֿ-לְבָבְךָ תִּתֵּן מַאֲכָל לַחֲרוֹן אֵין-אוֹנִים,

וְדִמְעָתְֿךָ הַגְּדוֹלָה הוֹרֵד שָׁם עַל קָדְקֹד הַסְּלָעִים

וְשַׁאֲגָתְֿךָ הַמָּרָה שַׁלַּח – וְתֹֿאבַד בִּסְעָרָה.

תמוז–תשרי, תרס”ד.

◊

Chaim Nachman Bialik’s Bisshuvósi

Note: See Alex Foreman’s youtube reading of the poem (and translation into English).

בִּתְֿשׁוּבָתִֿי Bisshuvósi

- שׁוּב לְפָנַי: זָקֵן בָּלֶה, Shuv ləfónay zókeyn bóle

- פָּנִים צֹמְקִים וּמְצֹרָרִים, Pónim tsoymkim umtsoyrórim

- צֵל קַשׁ יָבֵשׁ, נָד כְּעָלֶה, Tseyl kash yóveysh, nod kəólo

- נָד וָנָע עַל־גַּבֵּי סְפָרִים. Nod vonó al gábey səfórim

- שׁוּב לְפָנַי: זְקֵנָה בָלָה, Shuv ləfónay: skéyno bólo

- אֹרְגָה, סֹרְגָה פֻזְמְקָאוֹתֿ, Oyrgo, soyrgo puzməkóyoys

- פִּיהָ מָלֵא אָלָה, קְלָלָה, Pího móley ólo, klólo

- וּשְׂפָתֶֿיהָ תָּמִיד נָעוֹתֿ. Usəfosého tómid nóoys

- וּכְמֵאָז לֹא מָשׁ מִמְּקוֹמוֹ Ukhəmeyóz loy mosh mimkóymoy

- חֲתֿוּל בֵּיתֵֿנוּ – עוֹדוֹ הֹזֶה Khasul beyséynu — oydoy khóyze

- בֵּין כִּירַיִם, וּבַחֲלוֹמוֹ Beyn kiráyim uvakhalóymoy

- עִם־עַכְבָּרִים יַעַשׂ חֹזֶה. Im aghbórim yáas khóyze

- וּכְמֵאָז בָּאֹפֶל מְתֿוּחִים Ukhəmeyóz bo-óyfel məsúkhim

- קוּרֵי אֶרֶג הָעַכָּבִישׁ Kúrey éreg ho-akóvish

- מְלֵאֵי פִּגְרֵי זְבוּבִים נְפוּחִים Mley pígrey zvúvim nəfúkhim

- שָׁם בַּזָּוִיתֿ הַמַּעֲרָבִיתֿ… Shom bazóvis hamaaróvis

- לֹא שֻׁנֵּיתֶֿם מִקַּדְמַתְֿכֶם, Loy shunéysem mikadmáskhem

- יָשָׁן נוֹשָׁן, אֵין חֲדָשָׁה; – Yóshon nóyshon, eyn khadósho

- אָבֹא, אַחַי, בְּחֶבְרַתְֿכֶם! Óvoy, ákhay, bəkhevráskhem

- יַחְדָּו נִרְקַב עַד־נִבְאָשָׁה! Yaghdov nirkav ad-nivósho

◊

◊

◊

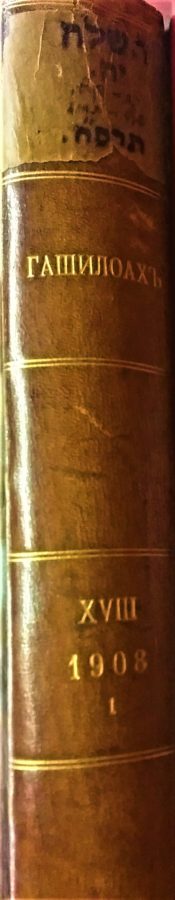

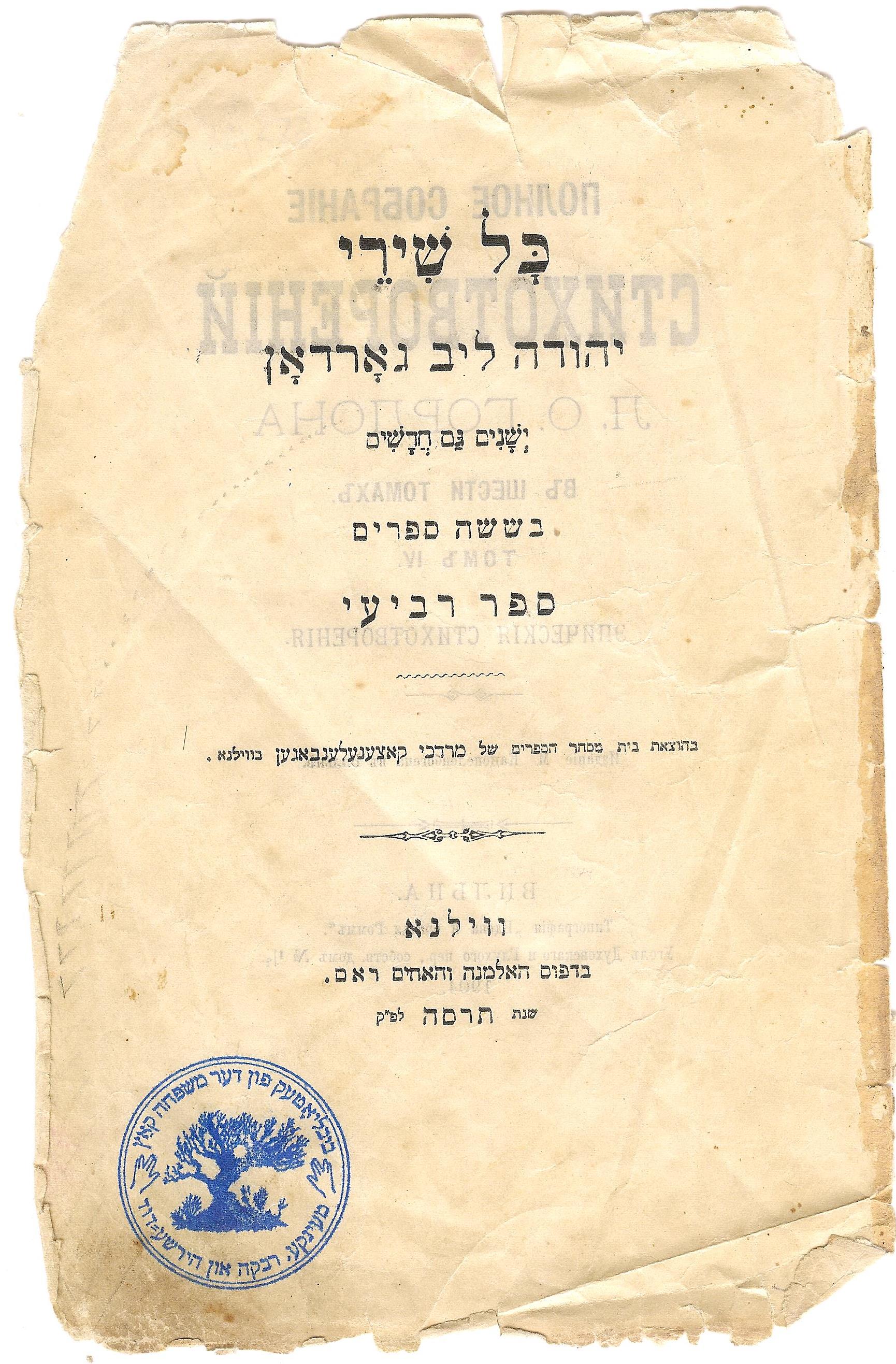

Yehudo Leyb Gordon יהודה לייב גאָרדאָן

הַסּוּס וְהַסִּיס

◊

Yehudo Leyb Gordon יְהוּדָה לֵיבּ גאָרדאָן

Hasús Vǝhasís הַסּוּס וְהַסִּיס

- ◊

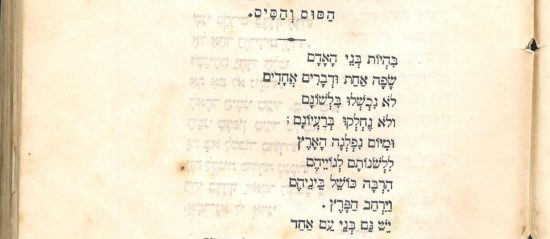

- בִּהְיוֹתֿ בְּנֵי הָאָדָם Bihyóys bney ho-ódom

שָׂפָה אַחַתֿ וּדְבָרִים אֲחָדִים Sófo ákhas udvórim akhódim

לֹא נִכְשְׁלוּ בִּלְשׁוֹנָם Loy níkhshǝlu bilshóynom

וְלֹא נֶחְלְקוּ בְּרַעְיוֹנָם; Vloy nékhlǝku bǝrayóynom - וּמִיּוֹם נִפְלְגָה הָאָרֶץ U-miyóym níflǝgo hoórets

לִלְשֹׁנוֹתָֿם לְגוֹייֵהֶם Lilshoynóysom lǝgoyéyhem

הִרְבָּה כּוֹשֵׁל בֵּינֵיהֶם Hírbo kóyshl beynéyhem

וַיִּרְחַב הַפָּרֶץ. Vayírkhav hapórets - ❊

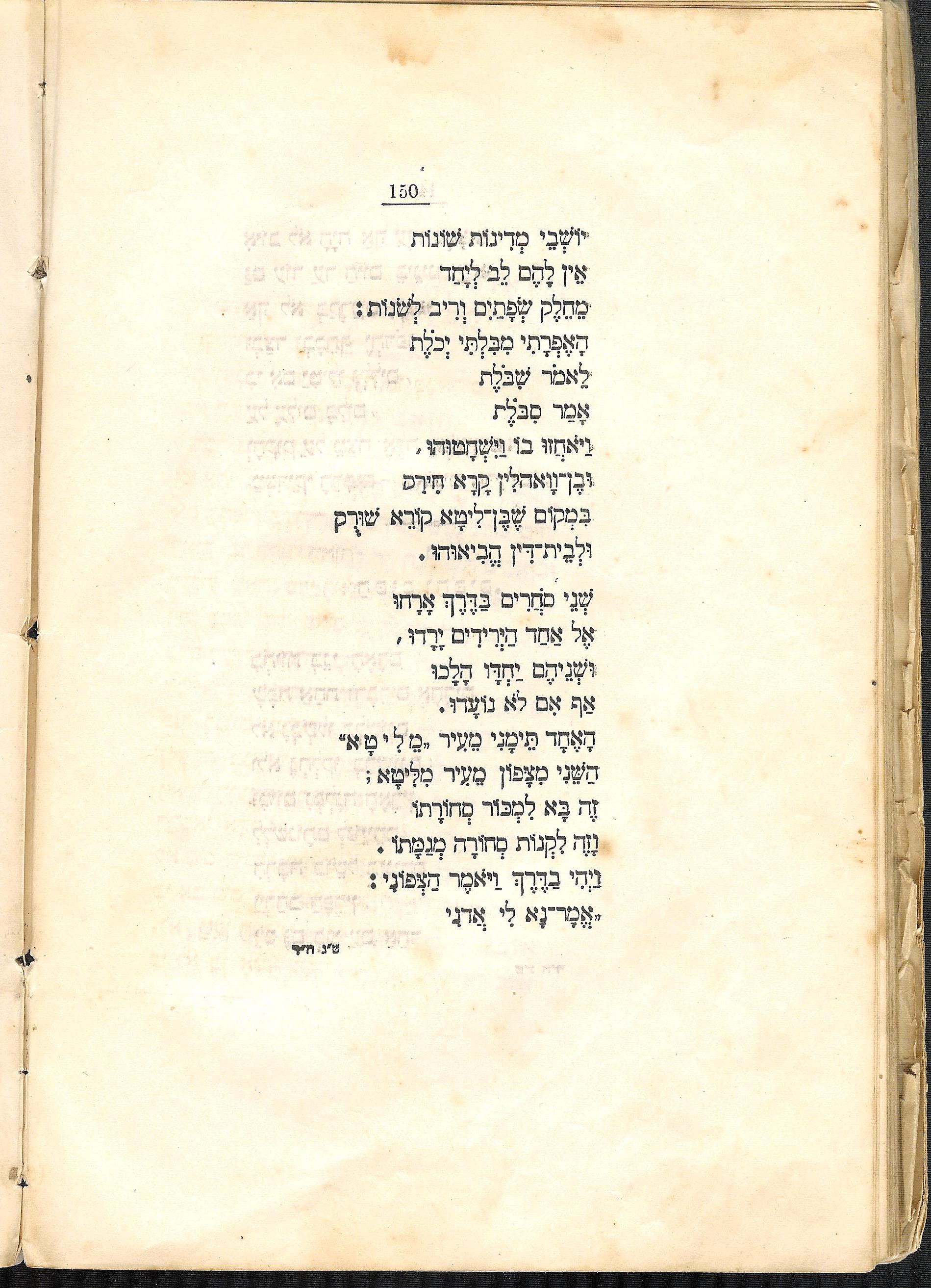

- יֵשׁ גַּם בְּנֵי עַם אַחַד Yeysh gám bney am ákhad

יוֹשְׁבֵי מְדִינוֹתֿ שׁוֹנוֹתֿ Yóyshvey mǝdínoys shóynoys

אֵין לָהֶם לֵב לְיָחַד Éyn lóhem leyv lǝyákhad

מֵחֵלֶק שְׂפָתַֿיִם וְרִיב לְשֹׁנוֹתֿ: Meykhéylek sfosáyim vǝrív lǝshóynoys - הָאֶפְרָתִֿי מִבִּלְתִּי יְכֹלֶתֿ Ho-efrósi mibílti yǝkhóyles

לֵאמֹר שִׁבֹּלֶתֿ Léymoyr shibóyles

אָמַר סִבֹּלֶתֿ – Ómar sibóyles

וַיֹּאחֲזוּ בוֹ וַיִּשְׁחָטוּהוּ, Va-yóykhazu bóy vayishkhotúhu - וּבֶן-וָואהלִין קָרָא חִירִיק Ubén Volín kóro khírik

בִּמְקוֹם שֶׁבֶּן-לִיטָא קוֹרֵא שׁוּרֻק Bímkoym she-ben-Líto kóyre shúruk

וּלְבֵיתֿ-דִּין הֱבִיאוּהוּ. Ulǝbézdn heviúhu - ❊

- שְׁנֵי סֹחֲרִים בַּדֶּרֶךְ אָרָחוּ Shney sóykhrim ba-dérekh orókhu

- אֶל אַחַד הַיְּרִידִים יָרָדוּ, El ákhad hayrídim yoródu

- וּשְׁנֵיהֶם יַחְדָּו הָלָכוּ Ushnéyhem yákhdov holókhu

אַף אִם לֹא נוֹעָדוּ. af ím loy noyódu. - הָאָחָד תֵּימָנִי מֵעִיר „מֵלִיטָא“ Hoékhod teymóni meyir Melíto

הַשֵּׁנִי מִצָּפוֹן מֵעִיר מִלִּיטָא; Hashéyni mitsófoyn meyir mi-Líto - זֶה בָּא לִמְכּוֹר סְחוֹרָתֿוֹ Ze bo límkoyr skhoyrósoy

וָזֵה לִקְנוֹת סְחוֹרָה מְגַמָּתֿוֹ. Vozé líknoys skhóyro mǝgamósoy.

וַיְהִי בַדֶּרֶךְ וַיֹּאמֶר הַצְּפוֹנִי: Vayǝhí badérekh vayóymer hatsfóyni

„אֱמָר-נָא לִי, אֲדֹנִי, Emóyr no lí adóyni

מַה-חֶפְצְךָ בַּשּׁוּק וּבשְׁבִיל מַה בָּאתָֿ?“ Ma khéftsǝkho bashúk ubíshvil ma bóso - וַיַּעַן הַדְּרוֹמִי: רְצוֹנִי Vayáan hadróymi: Rǝtsóyni

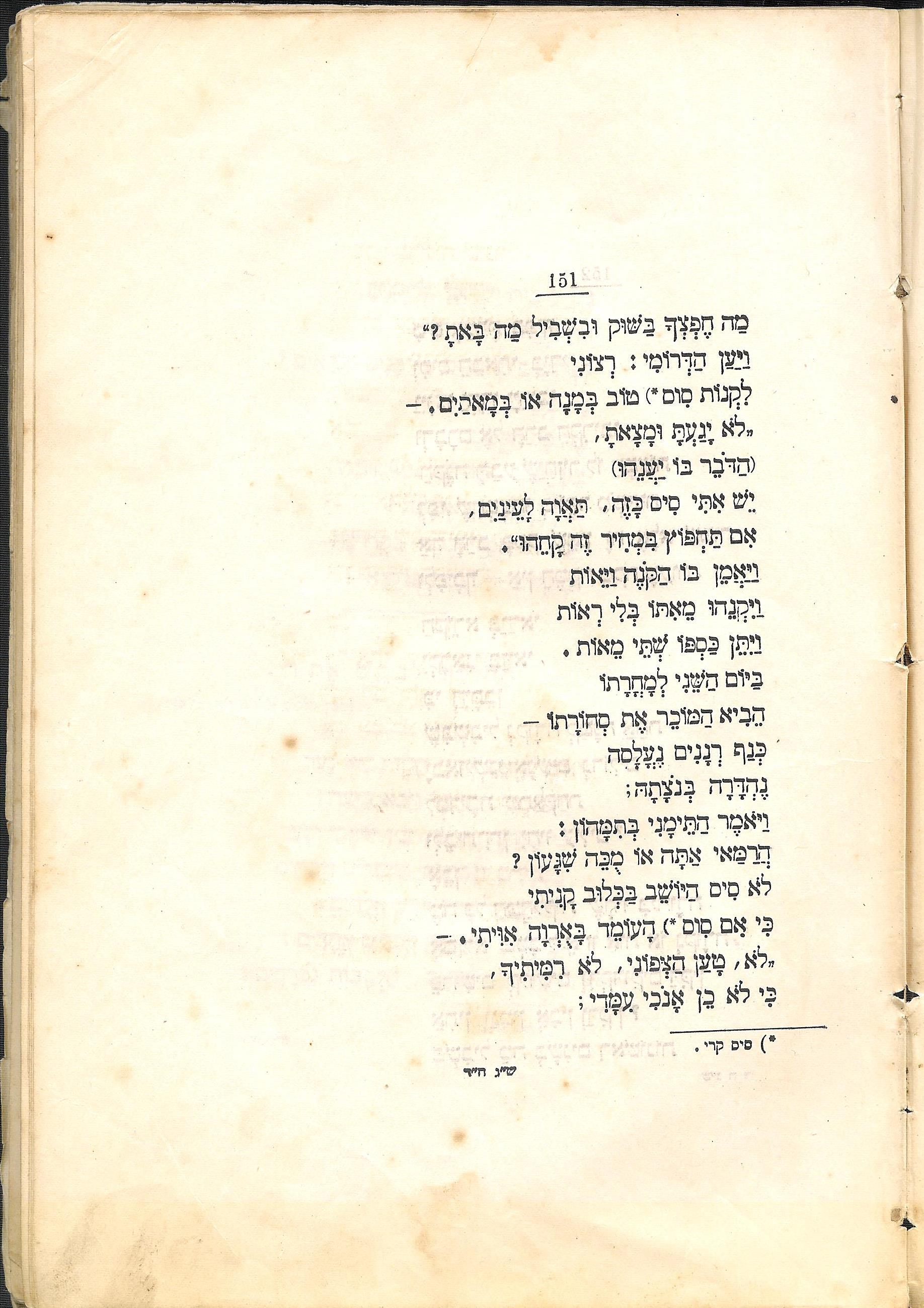

לִקְנוֹתֿ סִוס*) טוֹב בְּמָנָה אוֹ בְּמָאתַֿיִם — líknoys sis toyv bǝmóno oy bǝmosáyim - „לֹא יָגַעְתָּ וּמָצָאתָֿ“ Loy yogáto umotsóso

(הַדֹּבֵר בּוֹ יַעֲנֵהוּ), (Hadóyver bóy yaanéyhu)

„יֵשׁ אִתִּי סִיס כָּזֶה, תַּאֲוָה לָעֵינַיִם, Yeysh ití sis kozé, táyvo loeynáyim

אִם תַּחְפֹּץ בִּמְחִיר זֶה קָחֵהוּ“. Im tákhpoyts bimkhír ze kokhéyhu - וַיַּאֲמֵן בּוֹ הַקּוֹנֶה וַיֵאוֹתֿ Vayámeyn boy hakóyne vayéyoys

וַיִּקְנֵהוּ מֵאִתּוֹ בְּלִי רְאוֹתֿ, Vayiknéyhu meyítoy bli réyoys

וַיִּתֵּן כַּסְפּוֹ שְׁתֵּי מֵאוֹתֿ. Vayíteyn káspoy shtey méyoys - בַּיּוֹם הַשֵּׁנִי לְמָחֳרָתֿוֹ Bayóym hashéyni lǝmokhorósoy

- הֵבִיא הַמּוֹכֵר אֶתֿ סְחוֹרָתֿוֹ héyvi hamóykheyr es skhoyrósoy

- כְּנַף רְנָנִים נֶעֳלָסָה Knaf rǝnónim neelóso

נֶהְדָּרָה בְּנֹצָתָֿהּ Nehdóro bǝnoytsóyso - וַיֹּאמֶר הַתֵּימָנִי בְּתִמָּהוֹן: Vayóymer hateymóni bǝtimóǝn

הֲרַמַּאי אַתָּה אוֹ מֻכֵּה שִׁגָּעוֹן? Harámay áto oy múke shigóǝn - לֹא סִיס הַיּוֹשֵׁב בַּכְּלוּב קָנִיתִֿי Loy sis hayóysheyv bakúv konísi

- כִּי אִם סִוס הָעוֹמֵד בָּאֻרְוָה אִוִּיתִֿי. – Ki im sis hoóymeyd boúrvo ivísi

- „לֹא“, טָעַן הַצְּפוֹנִי, „לֹא רִמִּיתִֿיךָ, Loy, tóan hatsfóyni, Loy rimisíkho

- כִּי לֹא כֵן אָנֹכִי עִמָּדִי; Ki lóy keyn onóykhi imódi

סיס אָמַרְתָּ בְּפִיךָ Sis omárto bǝpíkho

וְסִיס הֵבֵאתִֿי בְּיָדִי“. vǝsis heyvéysi bǝyódi - וַיִּנָּצוּ יַחְדָּו וַיָּרִיבוּ Vayinótsu yakhdóv vayorívu

וּדְבָרָם אֶל הָרַב הִקְרִיבוּ. Udvorom el haróv hikrívu

הַקֹּנֶה תָּבַע שֶׁיַּחֲזִיר לוֹ הַמָּעוֹתֿ, Hakóyne tóva sheyákhzir loy hamóoys

לְפִי שֶׁהִטְעָהוּ בְּיוֹתֵֿר מִשְׁתּוּתֿ, Lǝfi shehitóhu bǝyóyseyr mishtús

אַךְ הָרַב פָּסַק שֶׁאֵין זֶה אֶלָּא שְׁטוּתֿ, akh haróv pósak sheéyn ze élo shtùs

וּלְפִיכָךְ – אֵין הַמֶּקַח מֶקַח טָעוּתֿ. Ulfíkhokh ― Eyn hamékah mékakh tóùs - הַקּוֹרֵא בְּוַדַּאי Hakóyrey bǝváday

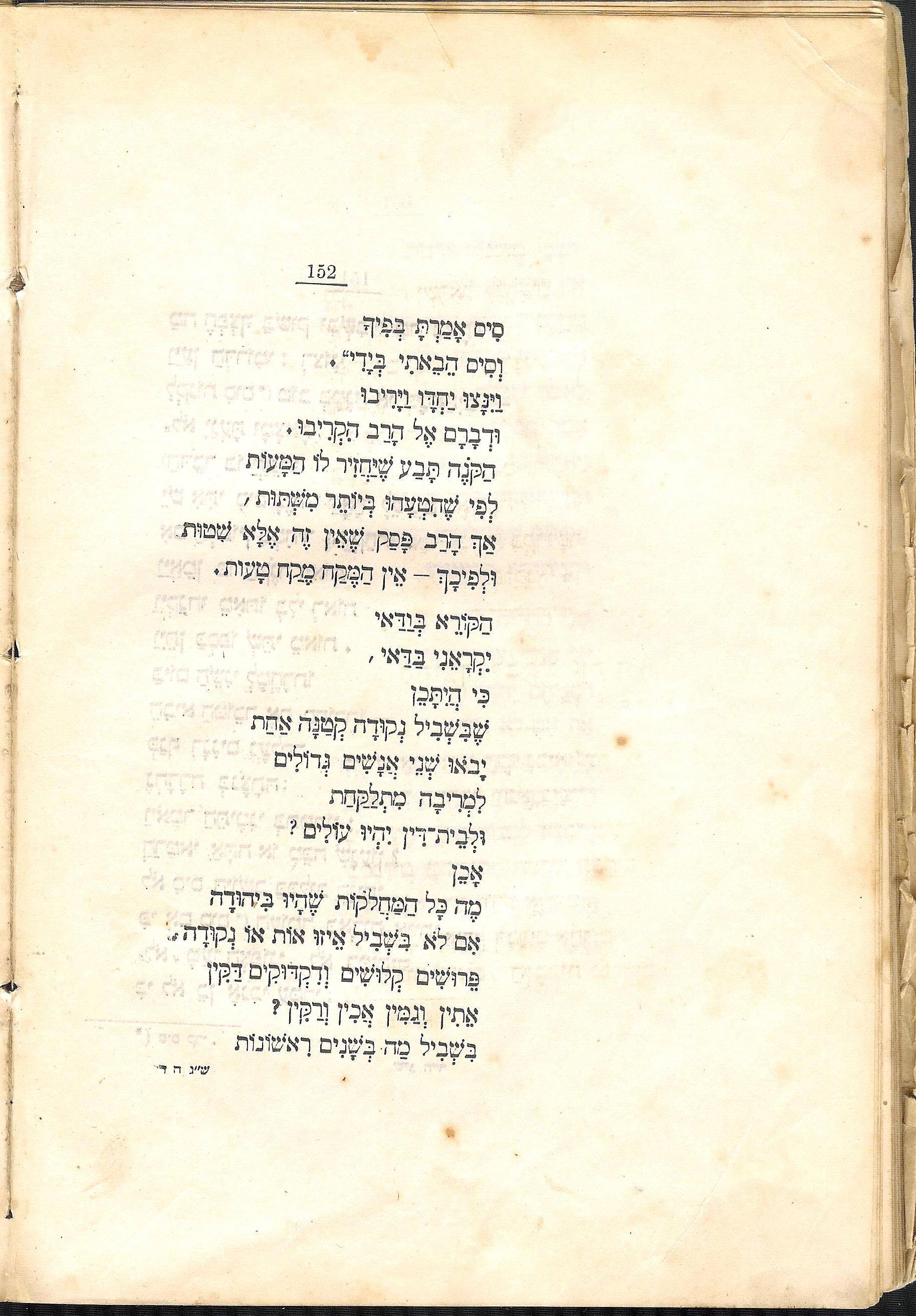

יִקְרָאֵנִי בַּדַּאי, Yikroéyni báday

כִּי הֲיִתָּכֵן Ki: Hayǝtókhn

שֶׁבִּשְׁבִיל נְקוּדָה קְטַנָּה אַחַתֿ shebíshvil nəkúdo ktáno akhás

יָבֹאוּ שְׁנֵי אֲנָשִׁים גְּדוֹלִים Yovóyu shney anóshim gdóylim

לִמְרִיבָה מִתְֿלַקַּחַתֿ Limrívo mislakákhas

וּלְבֵיתֿ-דִּין יִהְיוּ עוֹלִים? ulbézdn yíyhu óylim - ❊

- אָכֵן Okhéyn

מֶה כָּל הַמַּחֲלֹקוֹתֿ שֶׁהָיוּ בִּיהוּדָה Me kol hamakhlóykoys shehóyu biYhúdo

אִם לֹא בִּשְׁבִיל אֵיזוּ אוֹתֿ אוֹ נְקוּדָה. Im loy bishvil éyzu óys oy nǝkúdo - פֵּרוּשִׁים קְלוּשִׁים וְדִקְדּוּקִים דַּקִּין, Peyrúshim klúshim vǝdikdúkim dákin

אֵתִֿין וְגַמִּין אֲכִין וְרַקִּין? Éysin vǝgámin ákhin vǝrákin - בִּשְׁבִיל מַה בְּשָׁנִים רִאשׁוֹנוֹתֿ Bishvil má bǝshónim rishóynoys

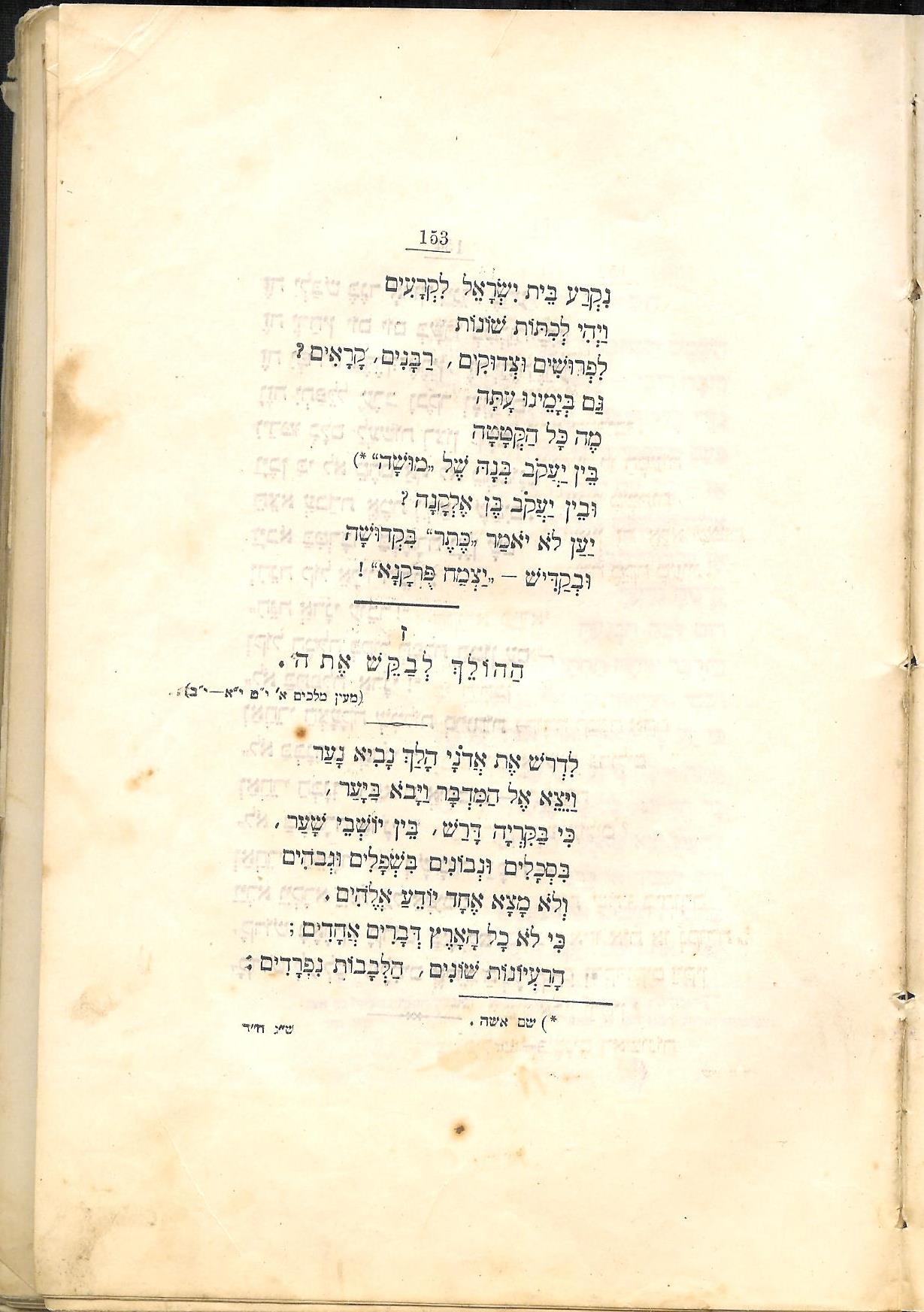

נִקְרַע בֵּיתֿ יִשְׂרָאֵל לִקְרָעִים Nikrá Beys Yisróeyl likǝróyim

וַיְהִי לְכִתּוֹתֿ שׁוֹנוֹתֿ Vayhí lǝkítoys shóynoys

לִפְרוּשִׁים וּצְדוּקִים, רַבָּנִים, קָרָאִים? LǝPrúshim uTsdúkim, rabónim, karóim - גַּם בְּיָמֵינוּ עָתָּה Gam bǝyoméynu óto

מַה כָּל הַקְּטָטָה Me kol haktóto

בֵּין יַעֲקֹב בְּנָהּ שֶׁל „מוּשָׁה“**) Beyn Yánkoyv bnó shel Músho

וּבֵין יַעֲקֹב בֶּן אֶלְקָנָה? Uveyn Yánkoyv bén Elkóno - יַעַן לֹא יֹאמַר „כֶּתֶֿר“ בִּקְדֻשָּׁה Yáan loy yóymar “késer” biKdúsho

- וּבְקַדִּישׁ — „יַצְמַח פֻּרְקָנָא“! UvǝKádish ― yítsmakh purkóno

- __________________

*) סיס קרי. **) שם אשה.

◊

Naftoli Hertz Imber נפתחי הערץ אימבר

◊

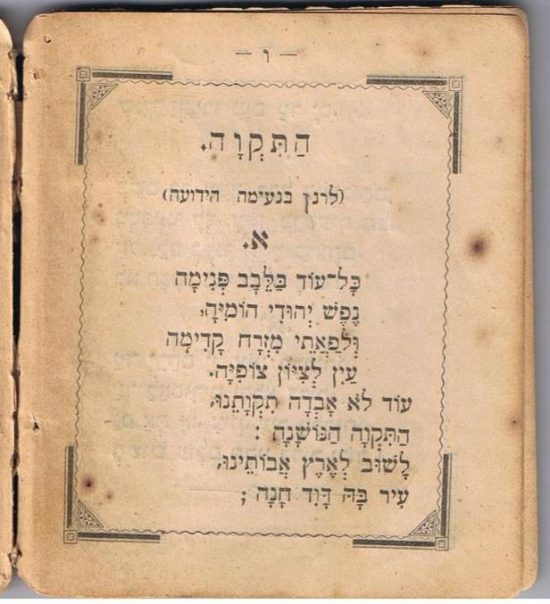

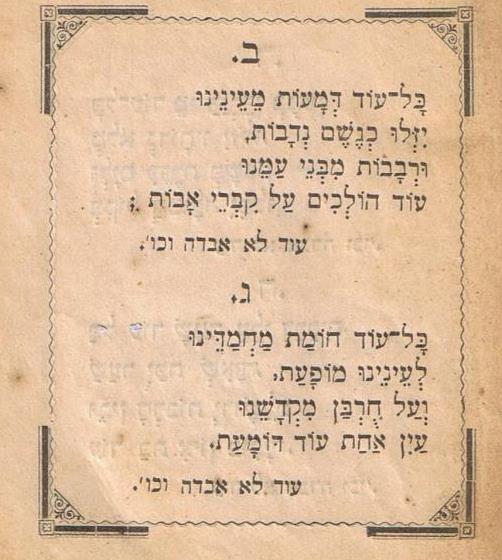

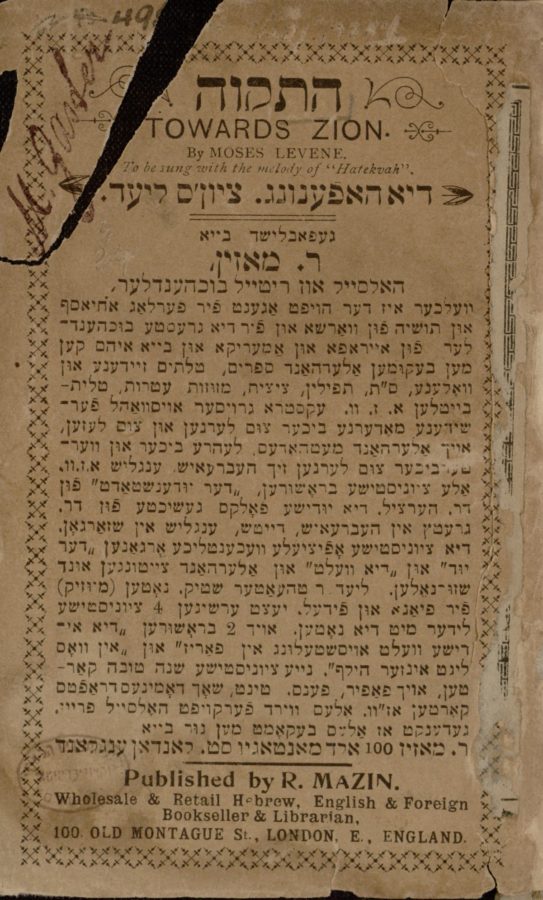

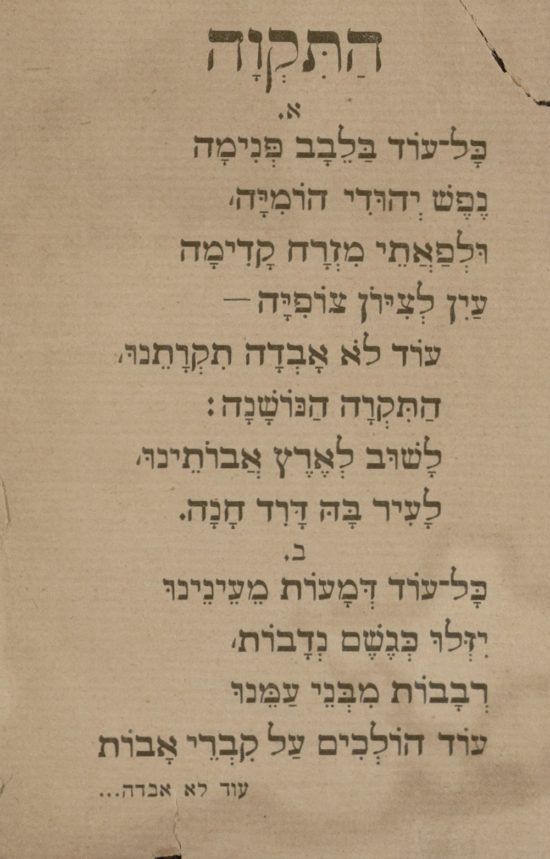

Naftoli Hertz Imber’s Hatikvoh (Hatikvah)

הַתִּקְוָה

SUNG IN 2021 BY

JOANNA CZABAN | אַשקע טשאַבאַן

MOSHE KOUSSEVITZKY

by AL JOLSON

Note differences: MK’s adherence to authentic Ashkenazic ‘oy for וֹ’ and plosive תּ word-initially (in תִּקְוָתֵֿינוּ) despite Tiberian cross-word-boundary spirantization norm).

◊

◊

◊

- Kol-òyd baléyvov — pənímo

- Nèfesh-yəhúdi —hoymíyo

- ulfaàsey-mízrokh — kodímo

- àyin-lətsíyoyn — Tsoyfíyo.

- ◊

- ❊

- ◊

- Oyd-lòy óvdo — tikvoséynu,

- hàtíkvo — hanoyshóno,

- lòshuv-ləérets — [èrets-] avoyséynu,

- ìr-bo Dóvid — [Dòvid-] khóno.

-

-

◊

-

In Warsaw Ashkenazic Hebrew

- ◊

- Kol-òyd baláyvov — pənímu

- Nèyfesh-yəhídi —hoymíyu

- ulfaàsay-mízrokh — kudímu

- à:(y)in-lətsíyoyn — Tsoyfíyu.

- ◊

- ❊

- ◊

- Òyd-loy óvdu — tikvusáyni,

- hatìkvu — hanoyshúnu,

- lùshiv-ləéyrets — [èyrets-] avoysáyni,

- ìr-bu Dúvit — [Dùvit-] khúnu.

-

- ◊

-

In Vilna Ashkenazic Hebrew

- ◊

- Kol-èyd baléyvov — pənímo

- Nèfesh-yəhúdi — heymíyo

- ulfaàsey-mízrokh — kodímo

- àyin-lətsíyeyn — Tseyfíyo.

- ◊

- ❊

- ◊

- Èyd-ley óvdo — tikvoséynu,

- hatìkvo — haneyshóno,

- lòshuv-ləérets — [èrets-] aveyséynu,

- ìr-bo Dóvid — [Dòvid-] khóno.

-

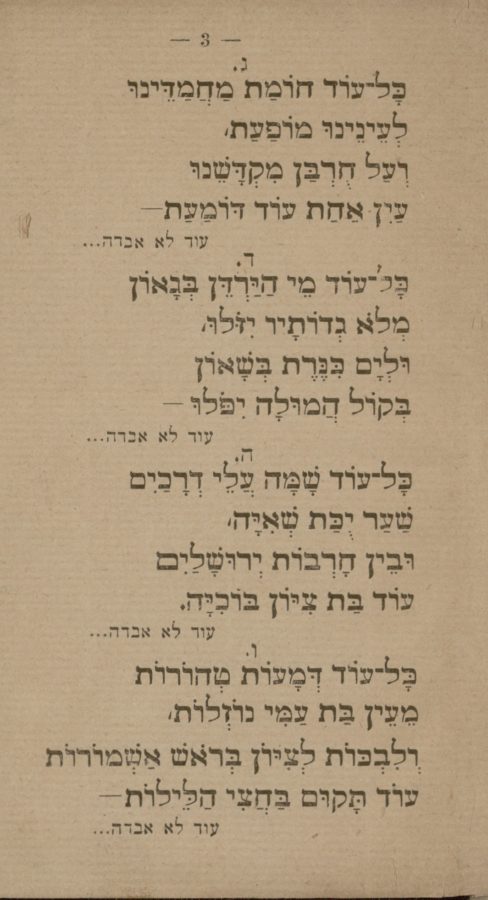

One of the versions of the entire poem

(published by Mazin’s of London, courtesy of Hebrew National & University Library, Jerusalem)

◊

The vowel pointing of the following version generally follows the original, with some occasional deviation resulting from popular rendition.

*

- כָּל עוֹד בַּלֵּבָב פְּנִימָה Kol oyd baléyvov p’nímo

נֶפֶשׁ יְהוּדִי הוֹמִיָּה Néfesh yəhúdi hoymiyo

וּלְפַאֲתֵֿי מִזְרָח קָדִימָה Ulfáasey mízrokh kodímo

עַיִן לְצִיּוֹן צוֹפִיָּה. Áyin l’tsíyoyn tsoyfiyo - ❋

- עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ Oyd loy óvdo tikvoséynu

הַתִּקְוָה הַנּוֹשָׁנָה Hatíkvo hanoyshóno

לָשׁוּב לְאֶרֶץ — אֶרֶץ אֲבוֹתֵֿינוּ lóshuv l’érets — érets avoyséynu

לָעִיר בָּהּ דָּוִד — דָּוִד חָנָה. Lo-ír bó Dóvid — Dóvid khóno - ❋

- כָּל עוֹד דְּמָעוֹתֿ מֵעֵינֵינוּ Kol oyd d’móoys mey-eynéynu

יִזְּלוּ כְּגֶשֶׁם נְדָבוֹתֿ Yízlu k’géshem nədóvoys

וּרְבָבוֹתֿ מִבְּנֵי עַמֵּנוּ Ur’vóvoys mibney améynu

עוֹד הוֹלְכִים עַל קִבְרֵי אָבוֹתֿ. Oyd hóylkhim al kívrey óvoys - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד חוֹמַתֿ מַחֲמַדֵּינוּ Kol oyd khóymas makhmadéynu

לְעֵינֵינוּ מוֹפַעַתֿ L’eynéynu moyfáas

וְעֲל חוּרְבַּן מִקְדָּשֵׁנוּ V’al khúrban migdoshéynu

עַיִן אַחַתֿ עוֹד דּוֹמַעַתֿ. Áyin ákhas oyd doymáas - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד מֵי הַיַּרְדֵּן בְּגָאוֹן Kol oyd mey-hayárdeyn b’gó-oyn

מְלֹא גְּדוֹתָֿיו יִזֹלוּ m’loy g’dóysov yizóylu

וּלְיַם כִּנֶּרֶתֿ בְּשָׁאוֹן Ul’yam kinéres b’shó-oyn

בְּקוֹל הֲמֻלָּה יִפֹּלוּ. B’koyl hamúlo yipóylu - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד שָׁמָּה עֲלֵי דְּרָכַיִם Kol oyd shómo áley d’rokháyim

שַׁעַר יֻכַּתֿ שְׁאִיָּה Sháar yúkas sh’íyo

וּבֵין חוּרְבוֹתֿ יְרוּשָׁלַיִם Uveyn khúrvoys y’rusholáyim

עוֹד בַּתֿ⸗צִיּוֹן בּוֹכִיָּה. Oyd bas-tsíyoyn boykhíyo - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד דְּמָעוֹתֿ טְהוֹרוֹתֿ Kol oyd d’mó-oys t’hóyroys

מֵעֵין בַּתֿ עַמִּי נוֹזְלוֹתֿ Mey-eyn bas-ámi nóyzloys

וְלִבְכּוֹתֿ לְצִיּוֹן בְּרֹאש אַשְׁמוֹרוֹתֿ V’lífkoys l’tsíyoyn broysh ashmóyroys

עוֹד תָּקוּם בַּחֲצִי הַלֵּילוֹתֿ. Oyd tókum bakhátsi haléyloys - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד נִטְפֵי דָם בְּעוֹרְקֵינוּ Kol oyd nítfey dom b’oyrkéynu

- רָצוֹא וָשׁוֹב יִזֹלוּ Rótsoy voshoyv yizóylu

- וַעֲלֵי קִבְרוֹתֿ אֲבוֹתֵֿינוּ Va-áley kívroys avoyséynu

- עוֹד אָגְלֵי טַל יִפּוֹלוּ. Oyd ógley tal yipóylu

- עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

- ❋

- כָּל עוֹד רֶגֶשׁ אַהֲבַתֿ הַלְּאוֹם Kol oyd régesh á(ha)vas-hal’óym

בְּלֵב הַיְּהוּדִי פּוֹעֵם B’leyv hay’húdi póyeym

עוֹד נוּכַל קַווֹתֿ גַּם הַיּוֹם Oyd núkhal kávoys gam hayóym

כִּי יְרַחֲמֵנוּ אֵל זוֹעֵם. Ki y’rakhméynu eyl zóyeym - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵנוּ…

- ❋

- שִׁמְעוּ אַחַי בְּאַרְצוֹתֿ נוּדִי Shímu ákhay b’ártsoys núdi

אֶתֿ קוֹל אַחַד חוֹזֵינוּ Es koyl ákhad khoyzéynu

„כִּי רַק עַם אַחֲרוֹן הַיְּהוּדִי Ki rák am ákhroyn hay’húdi

גַּם אַחֲרִיתֿ תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ“. Gam ákhris tikvoséynu - עוֹד לֹא אָבְדָה תִּקְוָתֵֿנוּ…

◊

Meyshe Kulbak: Three Hebrew Poems

With thanks to Siarhej Shupa (Prague) for providing these redsicovered Hebrew texts to be included in his forthcoming bilingual (Yiddish–Belarusian) edition of all of Kulbak’s poetry. These three poems, the only to have survived of Kulbak’s (early) Hebrew output, were first published in Di goldene keyt. Based on the Northern (Litvak) rhyme of בְּאֵרִי with מְזוֹרִי (as unitary ej) in the second poem, holem is transcribed ey throughout as per Kulbak’s Vilna area Yiddish and Hebrew.

◊

גַן סְתָּו. שְׁבִיל שְׁטוּף⸗הַצֵל…

Gan stov. Shvil shtuf-hatséyl

- גַן סְתָּו. שְׁבִיל שְׁטוּף⸗הַצֵל. Gan stov. Shvil shtuf-hatséyl

- אַתְּ, אֲנִי, וּדְמִי הַלֵיל. At. Ani, udmi haleyl

- כֶּסֶף-חַי בֵּין עֲלֵי פָּז. Kesef-khay beyn aley-póz

- אַתְּ, אֲנִי, וּטְהוֹר הָרָז… At, ani, uthoyr horóz

- יָד חֲרֵדָה, מַבַּט כְּאֵב, Yad karéydo, mabat kəéyv

- אַתְּ, אֲנִי, וּנְהִי הַלֵב. At, ani, unəhi ha-léyv

- סַהַר נוּגֶה, מִלַת דֹם. Sahar nugo, milas déym

- אַתְּ, אֲנִי, וּנְשִׁיקַת-חֹם. At, ani, unshíkas khéym

ר”ח חשון

Day Eykhóvey

דַי! אֵחָבֵא אֶל הַכֵּלִים

- ◊

- Day! Eykhóvey el hakéylim דַי! אֵחָבֵא אֶל הַכֵּלִים

- Shókto bəéyri… …שָׁקְטָה בְּאֵרִי

- Keshéykh ho-érev éteyn yod כְּשֹׁךְ הָעֶרֶב אֶתֵּן יָד

- Beléyv məzéyri בְּלֶב מְזוֹרִי

- *

- Gàley-mtsúlo shkhèyr-gabéykhem גַלֵּי מְצוּלָה! — שְׁחוֹר גַבֵּיכָם

- Rad al zhóvi. .רַד עַל זְהָבִי

- Khòrpi mámtin bèyn hashlógim… …חָרְפִּי מַמְתִּין בֵּין הַשְׁלָגִים

- Ləát — Lvóvi! !לְאַט — לְבָבִי

- *

- Lu evóseyr eyr la-láylo לוּ אֶוָתֵֿר עֵר לַלַּיְלָה

- Maaváyi מַאֲוַיִי

- Rəvàs-ha-néneshef eysht beyn tslólim רְוַתֿ-הַנֶשֶׁף אֵשְׁתְּ בֵּין צְלָלִים

- Ukhvor dáyi. .וּכְבָר דַיִי

- *

- Kòvu nəúray bətsèyl ha-khúrsheys כָּבוּ נְעוּרַי בְּצֵל הַחֻרְשׁוֹתֿ

- Bəeyd haplógim… …בְּאֵד הַפְּלָגִים

- Khòrpi mámtin bəkhèrdas-sháyish חָרְפִּי מַמְתִּין בְּחֶרְדַּתֿ-שַׁיִשׁ

- Beyn hashlógim. .בֵּין הַשְׁלָגִים

◊

בְּאַפְלוּלִיתֿ לֵיל אֵט עַתָּה אָהֳלִי…

Bəaflúlis leyl eyt ato ohóli

בְּאַפְלוּלִיתֿ לֵיל אֵט עַתָּה אָהֳלִי, Bəaflúlis leyl eyt ato ohóli

וְתֿוּגָה נוּגָה, רַכָּה עֶדְנַתֿ-כְָּנָף תִּשְׁמֹר סִפִּי… Vəsugo nugo, rako ednas-konof tishmeyr sipi

לַיְלָה. Láylo

חֶרֶשׁ, חֶרֶשׁ אֵצֵא אֶתֿ מְעוֹנִי Khéresh khéresh éytsey es məéyni

אָלִיט יָד בְּיָד, olit yod bəyod

וּמִשְׁנֵה דְמָמָה אִדֹם: umishney dəm omo odeym

אַלְלַי לִי! Aləlay li

דִמְעָה זַכָּה נִצְנְצָה בִּבְרַק⸗צְנִיעוּתָֿהּ. Dímo záko nitsnətso bivrak-tsniyúso

אַךְ בִּן לַיְלָה Akh bin láylo

חָרְדָה וְנִדְלָחָה… Khórdo vənidlokho

ּבַּמִסְתָּרִים פִּרְפְּרָה בִּדְמִי יְגוֹנָה נֶפֶשׁ תַּמָה, Bamistórim pirəro bidmey yegeyno nefesh tamo

רֶטֶט חַי עֲבָרָהּ וַתִּתְֿיַתֵּם… Retet khay avoro vətisyáteym

אָחִי, אָחִי, לֵיל נְדוּדִים! Okhi okhi, leyl nidudim

תְּכֶלְתְּךָ צַק לִי, רְוֵה נִשְׁמָתִי, וּבְהֶמְיָתְֿךָ רָן-נְכָאִים… Tkheyltəkho tsak li, revey nishmosi, uvəhemyoskho ron-nəkhóyim

דְמָמָה טְמִירָה, סֹבִּי דַלְתֵֿי לַיְלָה — Dmomo tmiro, seybi dalsey laylo

וְאֶל שְפוּנֵי שְׁחוֹר הַַתְּהוֹמוֹת שְאִי יְגוֹנִי Vəel shfuni shokheyr hatəheymeys səi yəgeni

יְגוֹן הַנֶפֶשׁ הָעֲיֵפָה… Yəgeyn ha-nefesh ho-ayeyfo

ּבְּגַעֲגוּעֵי-רְתֵֿתֿ אֲַחַכֶּה לָךְ… Bəgaguey-təseys akháke lokh

וָאֵבְךְ. Vo-eyvkh

בְּכִי עוֹלָל רַךְ עַל קֶבֶר אִמוֹ… Bəkhi eyleyl rakh al kever imey

ּוּבְהָנֵץ חַמָה, שוּלֵי שְׁמֵי מֶרְחַקִים יֶחֱוָרוּ, uvhoneyts khamo, shuli shmi merkhakim yokhevoru

גַל זִיו וְכֶסֶף יַךְ וְיִז בְּדִמְדוּמֵי שַׁחַר… Gal ziv v-khesef yakh v’yaz bədimdimey shákhar

אֲנִי — עֲרִירִי, Ani — ariri

וּלְבָדָד אֵלֵךְ עִם יְגוֹנִי, ulvodod eylekh im yegeyni

וְאֲתַֿנֶה חֶרֶשׁ כְּאֵב לְבָבִי בִדְמִי הַלֵיל Vəesáne khéresh kəeyv ləvóvi bidmi haleyl

בִּכְאֵב הָעוֹלָם… Bikhəeyv ho-eylom

ר”ח חשון

◊

◊

◊

◊

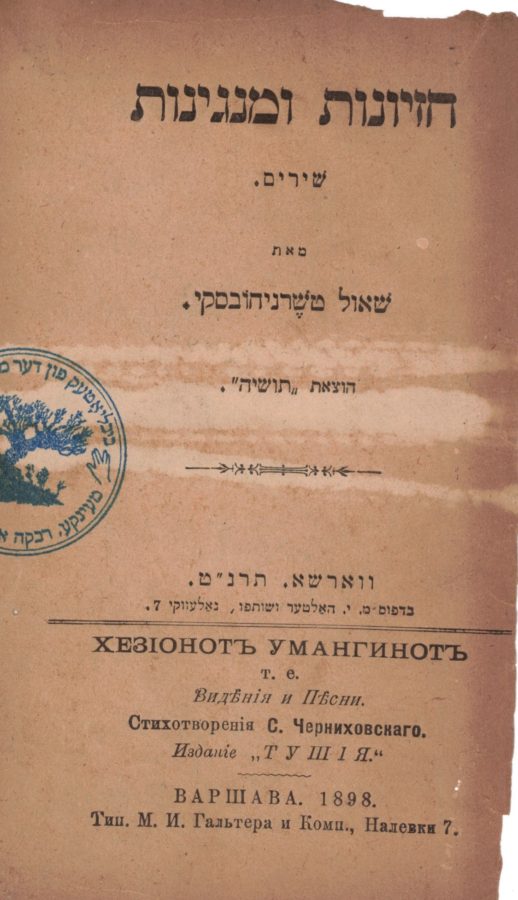

SUNG (2021) BY

JOANNA CZABAN | אַשקע טשאַבאַן

SIDOR BELARSKY (with American Ashkenazic oy:> o(u):)

◊

- The vowel pointing of the following version generally follows the original, with some occasional deviation resulting from popular rendition.

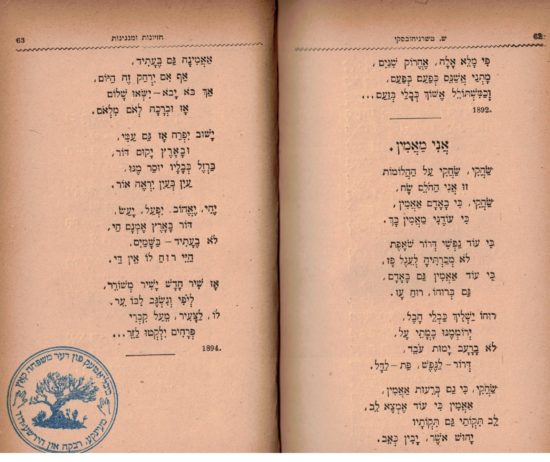

- שַׂחְקִי, שַׂחְקִי עַל הַחֲלוֹמוֹתֿ Sákhki, sákhki, al hakhalóymoys

- זוּ אֲנִי הַחוֹלֵם שָֹח Zu aní ha-khóyleym sókh

- שַׂחְקִי כִּי בָּאָדָם אַאֲמִין Sּákhki-kí bo-ódom áymin

- כִּי עוֹדֶנִּי מַאֲמִין בָּךְ Ki oydéni máymin bókh

- *

- כִּי עוֹד נַפְשִׁי דְּרוֹר שׁוֹאֶפֶתֿ Ki oyd náfshi dróyr shoyéfes

- לֹא מְכַרְתִּיהָ לְעֵגֶל פָּז loy mkhartího léygel póz

- כִּי עוֹד אַאֲמִין גַּם בָּאָדָם Ki òyd áymin gam bo-ódom

- גַּם בְּרוּחוֹ, רוּחַ עָז Gam b’rúkhoy, rúakh óz

- *

- רוּחוֹ יַשְׁלִיךְ כַּבְלֵי הֶבֶל Rúkhoy yáshlikh kávley hével

- יְרוֹמְמֶנּוּ בָּמְתֵֿי עָל Y’róyməménu bómsey ól

- לֹא בָּרָעָב יָמוּתֿ עוֹבֵד Loy bo-róov yòmus óyveyd

- דְּרוֹר – לַנֶּפֶשׁ, פַּתֿ – לַדָּל Droyr — lanéfesh, pas — ladól

- *

- שַׂחְקִי כִּי גַּם בְּרֵעוּתֿ אַאֲמִין Sàkhki-kí gam brèyus áymin

- אַאֲמִין, כִּי עוֹד אֶמְצָא לֵב Àymin-kí oyd èmtso léyv

- לֵב תִּקְוֹתַֿי גַּם תִּקְוֹתָֿיו Leyv tikvóysay, gam tikvóysov

- יָחוּשׁ אֹשֶׁר, יָבִין כְּאֵב Yókhush óysher, yòvin kéyv

- *

- אַאֲמִינָה גַּם בֶּעָתִֿיד Aamíno gam be-ósid

- אַף אִם יִרְחַק זֶה הַיּוֹם Af im yírkhak ze hayóym

- אַךְ בֹּא יָבוֹא – יִשְּׂאוּ שָׁלוֹם Akh boy-yóvoy — yísu shóloym

- אָז, וּבְרָכָה לְאֹם מִלְאֹם Oz, uvrókho l’óym-milóym

- *

- יָשׁוּב יִפְרַח אָז גַּם עַמִּי Yóshuv yífrakh oz gam ámi

- וּבָאָרֶץ יָקוּם דּוֹר Uvo-órets yókum dóyr

- בַּרְזֶל כְּבָלָיו יוּסַר מֶנּוּ Bàrzel-kvólov yúsar ménu

- עַיִן בְּעַיִן יִרְאֶה אוֹר Ayin-b’áyin yíre óyr

- *

- יִחְיֶה, יֶאֱהַב, יִפְעַל, יָעַשׂ Yìkhye, yéhav, yífal, yóas

- דּוֹר בָּאָרֶץ אָמְנָם חַי dóyr bo-órets ómnom kháy

- לֹא בֶּעָתִֿיד – בַּשָּׁמַיִם loy be-ósid — bashomáyim

- חַיֵּי רוּחַ לוֹ אֵין דַּי Kháyey-rúakh loy eyn dáy

- *

- אָז שִׁיר חָדָשׁ יָשִׁיר מְשׁוֹרֵר Oz shir-khódosh yóshir mshóyreyr

- לְיֹפִי וְנִשְׂגָּב לִבּוֹ עֵר L’yòyfi-vnízgov líboy éyr

- לוֹ, לַצָּעִיר, מֵעַל קִבְרִי Loy, la-tsóir, méy-al kívri

- פְּרָחִים יִלְקְטוּ לַזֵּר Prókhim yilk’tu la-zéyr

- ◊

-

See also Y. Y. Shvarts’s Yiddish translation (as PDF).

◊

◊

Shóko Khámo שקעה חמה

◊

שָׁקְעָה חַמָּה שָׁקְעָה נַפְשִׁי Shóko khámo, shóko náfshi

בִּתְֿהוֹם יְגוֹנָהּ הָרַב כַּיָּם bis’hóym y’góyno horáv kayóm

כִּי עוֹמְדָה לִפֹּל הִיא בְּמִלְחַמְתָּהּ ki ómdo lípoyl hi b’milkhámto

אֶתֿ הַבָּשָׂר וְאֶתֿ הַדָּם es habósor v’es hadóm