PERSON OF THE YEAR | LITHUANIA | JULIUS NORWILLA | LITVAK AFFAIRS | HUMAN RIGHTS | HISTORY

◊

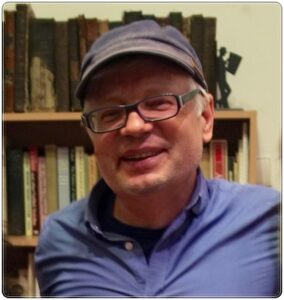

The journey of Julius Norwilla (Norvila) comprises the dynamic persona of: a child in Soviet-era Kaunas; a young intellectual dissident (of religious persuasion) in the waning days of the Soviet Union; theology student at Tallinn and Oxford; Protestant pastor in Vilnius; champion of all the minority people and cultures in Lithuania; love of the Lithuanian Jewish heritage and standing up against state efforts to manipulate that heritage and its history; intense study of Yiddish; combating Holocaust obfuscation and public worship of Holocaust participants (including peaceful, dignified protest at, and photo documentation of, each neo-Nazi march over many years); central figure in the movement to preserve Jewish cemeteries and mass graves; beloved teacher; and — through it all a rare paragon of personal steadfastness, loyalty, and integrity, equally unshakeable by offers of largesse, mammon, and career glories from one side or — by threats of personal and career destruction from the other.

The journey of Julius Norwilla (Norvila) comprises the dynamic persona of: a child in Soviet-era Kaunas; a young intellectual dissident (of religious persuasion) in the waning days of the Soviet Union; theology student at Tallinn and Oxford; Protestant pastor in Vilnius; champion of all the minority people and cultures in Lithuania; love of the Lithuanian Jewish heritage and standing up against state efforts to manipulate that heritage and its history; intense study of Yiddish; combating Holocaust obfuscation and public worship of Holocaust participants (including peaceful, dignified protest at, and photo documentation of, each neo-Nazi march over many years); central figure in the movement to preserve Jewish cemeteries and mass graves; beloved teacher; and — through it all a rare paragon of personal steadfastness, loyalty, and integrity, equally unshakeable by offers of largesse, mammon, and career glories from one side or — by threats of personal and career destruction from the other.

Such incentives sometimes come into play in the context of campaigns of defamation and personal destruction of colleagues; here is a human being who would never touch such tactics with a bargepole. Verily, such steadfastness and integrity is a rarefied trait when it comes to painful Jewish issues and history in the Baltics. All in the face of major powers and forces in a part of the world where respect for free speech and diversity of views continues to be a work in progress or, not infrequently, a public relations illusion. For close to a decade: author at Defending History.

Among many highpoints is his historic 2017 speech at the Lithuanian Embassy in Tel Aviv concerning plans for the Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery to be defiled by renovation (instead of removal) of a Soviet eyesore plonked in the middle of the beloved old cemetery. Another is his unique challenge (“Russian Warship, Go F**k Yourself!“) (with a version in Lithuanian media too) to the government’s view that the Soviet building plonked in the heart of the Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery is some kind of national treasure that cannot be touched (when so many other Soviet monstrosities are readily dismantled, even deep in cemeteries, even those commemorating the defeat of Nazism).

Meet our previous Persons of the Year

Ever the intrepid documentarian, Julius takes and posts dozens of photos of meaningful events for the record of history. In June 2020, a small Defending History team led by Julius monitored the far right Vilnius celebration of June 23rd 1941 (the day the Holocaust broke out in Lithuania; to ultranationalists, the day to celebrate an “uprising” that never happened). A year later, in 2021, Defending History alone reported that the newly appointed director general of the state-sponsored Genocide Center had in June 2020 given a rousing far-right speech at that event flanked by huge posters of two infamous Holocaust perpetrators, J. Noreika and K. Škirpa. Within minutes of our report, social media got flooded with accusations (including members of a major state commission) that this was a malicious photoshop. The DH team quickly linked to Julius’s online album of the event with dozens of images (see our report). No photoshops. Just the facts.

Because of the stranglehold of state-sponsored Holocaust revisionism on Judaic and Yiddish studies in Vilnius, Julius’s successful Yiddish teaching could not find a professional home here in Vilnius, very sadly. So, in addition to continuing his Vilnius class online (gratis), Julius now teaches Yiddish regularly to an enthusiastic group of people of diverse backgrounds down south in Bialystok, Poland. That’s our Julius. And this too will be remembered in the storied annals of Vilna Jewish lore and its propensity for exporting Jewish learning near and far. In a generation or so, Lithuania will know who were its true patriots in our own times. Julius will figure prominently in that pantheon.

Instead of further editor’s narrative, the team has this year asked the new Person of the Year to write his own memoir and accompany it with a selection of photographs. So, here is Defending History’s Person of the Year, Julius Norwilla (Norvila), in his own words. . .

❊

◊

From the Story of My Life

by Julius Norwilla

Kaunas (Kóvne) is my hometown, where I was born in 1955, and raised by an extended family, primarily my grandparents on my mother’s side. Grandmother Maria (nee Kizevičius) took care to ensure that her grandchildren received a more or less systematic Catholic upbringing and spiritual training. When my peers were enjoying Soviet state-funded folk dances and singing activities, I spent hours contemplating God, humanity, Catholic doctrines and pronouncements, and those of other religions. Repeatedly, I was warned by those who cared about me not to trust anyone and not to share my thoughts and experiences with anyone, because that could lead to big trouble from our authorities, not only for me, but for my friends and family too.

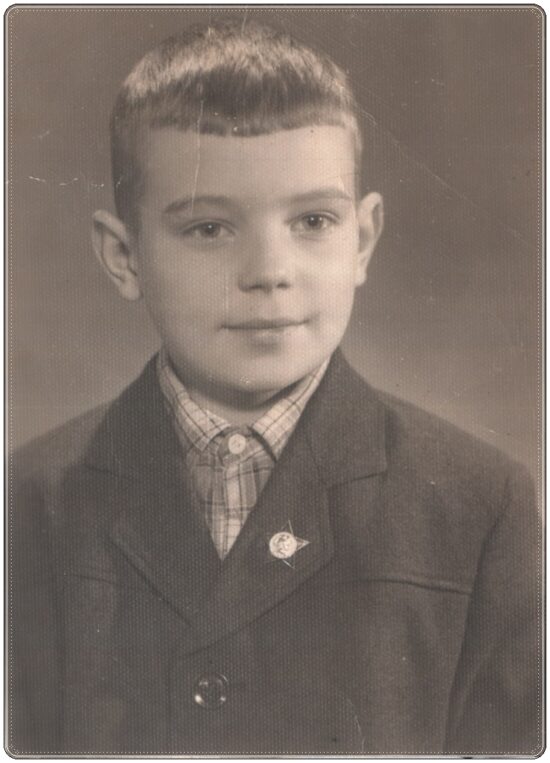

Aged 11, enrolled in a boarding school at Prienai (Yiddish: Pren)

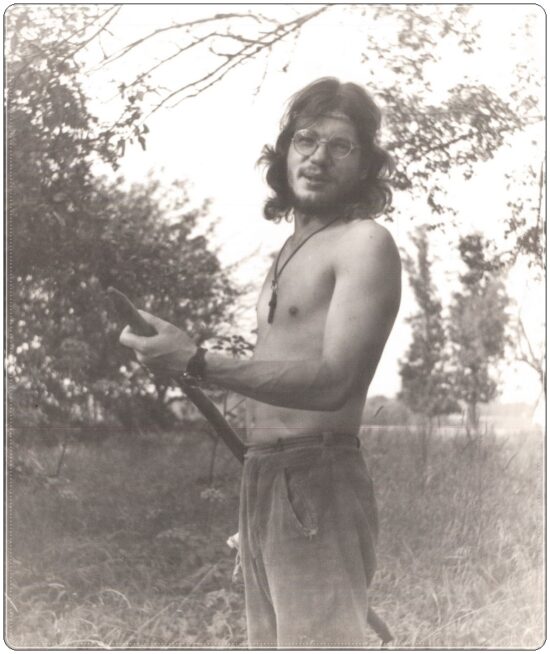

In 1978 I graduated from the Kaunas University of Technology as a civil engineer and relocated to Vilnius (Vílne). In the nineteen-eighties, I became deeply involved in the semi-underground free Christian movement. That meant crossing the red line. In the Soviet Union, one may be religious as much as one likes, provided his or her activities are within the limits of — and this is the main point — controlled by the authorities. These semi-underground religious activities were actively suppressed with no compromises or delays. Right up to taking children away and putting them, and parents or other adults accused of inspiring them, right into prison. People in the West don’t always understand that religiously motivated dissidents were part of the wider dissident population, and the style of the dissident was to adopt the hippie look.

A God-loving hippie in the Lithuanian Soviet Republic (1980)

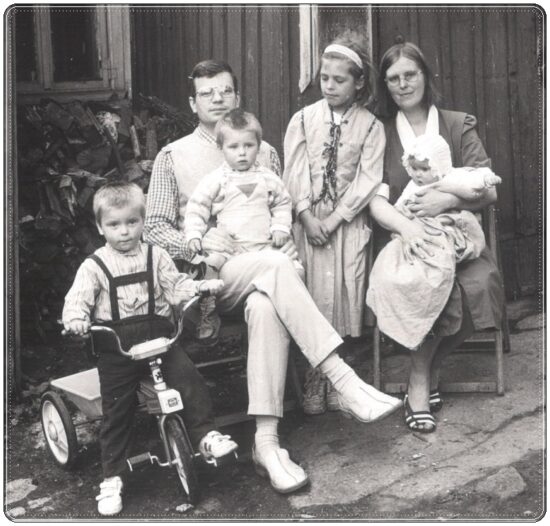

In 1984 I married Vitalija (nee Biguza) and we went on to raise our four beautiful children.

Vitalija and Julius, with our four children. From left: Povilas (on tricycle), Timotiejus, Kristina, and the youngest, Salomeja (on Vitalija’s lap).

By 1988, deep in the years of glasnost and perestroika, I was able to openly start formal studies in Theology in Tallinn, Estonia. The next year, the Protestant (Evangelical Reformed) Church, a minority church in Lithuania, invited me to become a minister. Looking back, accepting such an invitation was highly unusual. In 1989 even the brightest minds didn’t really know what was going to happen in the Soviet Union in the next few years (so very different from the question of what they might have liked to happen). In 1989, at the General Assembly of the World Alliance of Reformed Churches, by general vote, I was elected to be a member of the Executive Committee. Work on the various committees exposed me to social and political issues on a wider scale, both conceptually, and in terms of practical projects and plans. That was when another paradox in my life, as some friends saw it, was in play, when I was a protestant church minister at the same time I was teaching courses on Social Doctrine at the Catholic college. For me though, there was no contradiction, as I contemplated the majesty of the world’s faiths.

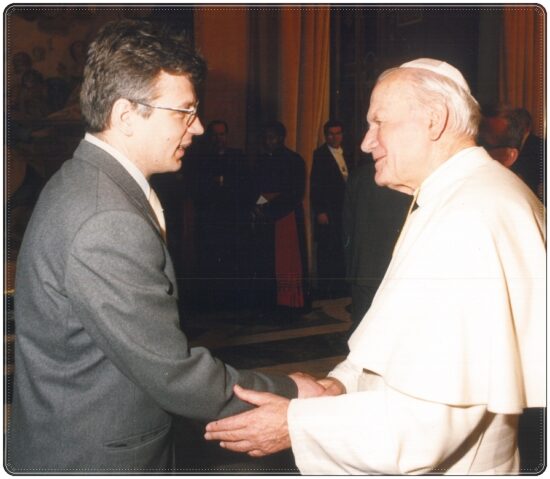

In 1990 I was a student at Geneva University and the Ecumenical Institute of the World Council of Churches. The program included a visit to the Vatican and an audience with Pope John Paul II. The pope was surprised when I greeted him in Polish. Then his secretary came over to speak some more, in Polish.

In 1990, the Soviet Union ceased to exist in many ways (it was only in 1991 that it officially and totally ceased to exist) and we found ourselves in an utterly new, and for many, an intractable political and economic reality.

Believe it or not, many former communists became religious conservatives overnight, and state-and-church relations entered a kind of honeymoon phase. Former dissidents were taken by surprise and very soon found that they (/we) no longer had any space in church institutions. In other words, Soviet-era relations between easily defined groups (like a nomenklatura or party vs. simple folks) sometimes continued intact, just in utterly new frameworks and belief systems.

In 1993 I was elected as executive director of the National Council of Churches (NCC), a partner to the government in those years of transition. But instead of working in partnership with the NCC, the government established an office of a formal Representative with a budget for distribution for mainstream churches at his own discretion, and, it seemed, for the benefit of his own circles. One year later it became obvious that the NCC had little to no support from mainstream church offices. Instead of working in partnership and encouraging ongoing dialogue, and fear-free open discussion, the government managed to return rapidly to Soviet-style management.

Leading a March 1992 protest in the form of a worship service on the street in front of a Kaunas church which was still being used as a sports center.

Nevertheless, the more or less peaceful transition to national independence and political freedom, and the advent of real freedom of consciousness and religious practice, were genuine miracles of my lifetime.

In the nineteen-nineties, the dedicated processes of accession to the EU and NATO (a process completed in 2004) accelerated freedom of speech among the Lithuanian literary, and culturally elite classes. However, freedom of speech in the hands of the state, with all its resources, also opens the door to industrial-scale manipulation of historical facts and twisting of collective memory, especially concerning the Holocaust in Lithuania. As a church minister committed to interreligious dialogue and ecumenism, I was open, and had always been open, to learning in depth about Jewish traditions, and especially Litvak culture, and naturally, about the Holocaust in Lithuania. In Lithuania, there are 230 marked places of mass murder of some 96% of the country’s Jews (one of the highest rates in all of Holocaust-era Europe; to this day, official press releases have to say “90%”, such are the minutia of state-dictated history). I began as a matter of principle to make time and arrangements for visiting more and more of these sites, reporting on their condition and on-site documentation of the events that transpired there. In a perhaps quixotic spirit, I have over the years been reporting vandalism, deficiencies, and fake-history inscriptions to law enforcement, always asking them to start an investigation (they cannot often hide their amazement that someone speaking native Lithuanian is phoning them about these Jewish places).

Then, working closely with the team at Defending History, I began to systematically monitor, document and publish reports on the regular neo-Nazies marches and events that took place on national holidays, in central Vilnius , central Kaunas, and other public spaces, usually with the blessing of the authorities. These marches and other events did not call for violent action against any non-existent or tiny minorities in Lithuania (though they abounded in shouts of “Lithuania for Lithuanians!”, “Without Jews, Without Poles, Without Russians!”). Their primary aim, on the point of glorification of Hitlerist collaborators in concert with many “patriotic politicians” was meant to glorify local Nazi collaborators as “freedom fighters” and “national heroes.” Looking back, these far-right marches are, it seems, evolving to a more moderate mode, for the most part. We may assume that it is partly due to Defending History’s detailed and accurate reports. However, no one in Lithuania has ever offered a word of gratitude for our work and face-to-face encounters with the threatening neo-Nazis (see DH’s sections on far right marches, and on marches in Kaunas; marches in Vilnius; and Riga). After a decade of monitoring the neo-Nazi marches and antisemitic events, and being pleased to serve on the editorial staff of DefendingHistory.com, I should also mention that I have never seen one representative of the well-funded “human rights organization” based in Vilnius. But they do have lovely websites of the highest calibre and offer impressive speeches at international conferences.

With Dovid, after we (and other Defending History colleagues) monitored and documented an independence day march featuring huge placards of local Holocaust collaborators. Celebrating our safe completion of the mission, and thinking about a better future…

For me, the fate of the Old Piramónt Jewish Cemetery in Vilnius (in Šnipiškės, Vilnius) is a unique subject of deep spiritual importance and contemporary — and future — import, whose resolution will have a lot to say about the ethical future of our country. As a pantheon of Litvak civilization, the ancient Jewish cemetery in Vilnius suffers from state-encouraged land grabbing. In the seventies, the Soviets built the monstrous Palace for Concerts and Sports right in the middle of the cemetery. The large dilapidated structure was abandoned twenty years ago for safety reasons. Our generation is a witness to the twisted proclamation of the Soviet eyesore to be some kind of a national treasure (nonsense; it’s a case of brutalist Soviet cultural rape of a proud and ancient capital city) as excuse for not taking it down to restore the beautiful cemetery (as would of course be the case if there were texts for hundreds of Lithuanian Christian gravestones that could be readily reconstructed). Unfortunately, there is a lack of will to do the right thing and restore the cemetery. To make matters much worse, two modern buildings, housing businesses and apartments (the “two green buildings“) were built in the twenty-first century with Lithuanian government blessing and support, yes — within the EU and NATO.

Top left: With major Litvak rabbis in Tel Aviv in a formal delegation to the Lithuanian Embassy to politely protest plans to reconstruct the Soviet “Sports Palace” instead of removing it to lovingly restore the Old Vilnius Jewish Cemetery at Piramónt. Bottom left: Delivering petition to the Vilnius Municipality, with Ruta Bloshtein and Rabbi Samuel Jacob Feffer. At right: Lone protest at Turto Bankas, the state’s “property bank” which has been pursuing vast (and allegedly corrupt) commercial gain from desecration and destruction of the Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery.

Not trusting translations, I determined to learn Yiddish. There I should mention that in the eighties I managed to learn Polish, of which I am very proud. Believe me, Polish opens a very different understanding of my own country, Lithuania, and is much deeper than what is taught at our universities. The same applies to learning Yiddish. Polish and Yiddish should be taught at the secondary school level, perhaps in the context of a series of “regional language” options students can choose from. This is an absolute minimum and not some over-the-top extravaganza.

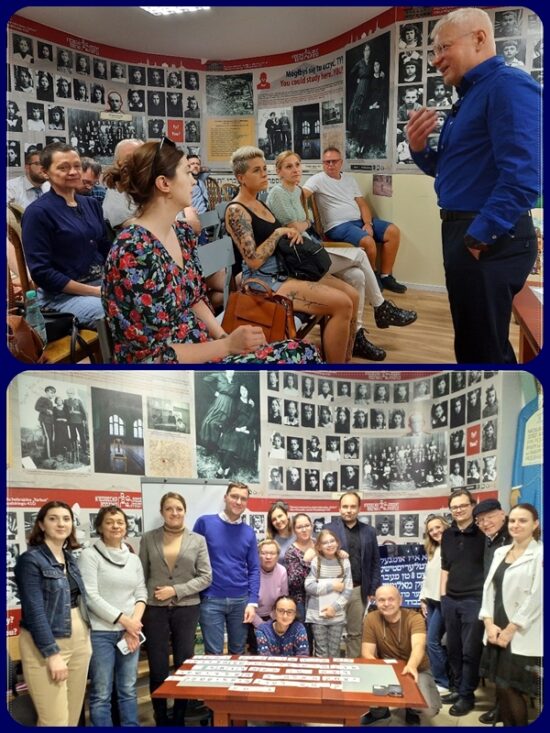

I was privileged to study Yiddish for many years as a regular participant in Dovid Katz’s Vilna Yiddish Reading Circle (which met weekly without missing a beat for 21 years, 1999-2020), at Vilnius summer courses, and thanks to Yivo, a summer in New York too. I then initiated an elementary course in 2019 and have been privileged to teach this wonderful, diverse group for four years. This year, I accepted a gracious invitation to commute to Bialystok in Poland each month to teach Yiddish to a group of some twenty students from numerous backgrounds and age groups, many of the younger generation. I recently received their letter of greetings for Christmas and the New Year, written in fine Yiddish.

Late 2023: Teaching Yiddish in Bialystok (top), and recreating a Yiddish inscription from the city with Yiddish text honoring heroic ghetto fighter Yitskhok Malmed. With the help of an enlarged text on the screen, we are putting the text together at the table using “physical” Yiddish letters. The inscription was affixed many decades ago in his memory, and today it is one of many locally relevant tools for the study of the living language and culture of East European Jewry.

◊

◊