[last update]

◊

see also: BOOKS SECTION

[last update]

see also: BOOKS SECTION

◊

◊

On July 1944, Convoy 77 left the internment camp of Drancy in France, three weeks before the liberation of Paris. The destination was Auschwitz-Birkenau. Eight Litvaks living in France were deported, of whom only one survived the war. The association of the deportees of Convoy 77 would receive the sponsorship of the French Presidency which commissioned schools in France and abroad to research and reconstruct their lives in France and their last days. The project was to “put adolescents in charge not of a sepulchral memory but of the reconstitution of life paths more than death paths.”

On July 1944, Convoy 77 left the internment camp of Drancy in France, three weeks before the liberation of Paris. The destination was Auschwitz-Birkenau. Eight Litvaks living in France were deported, of whom only one survived the war. The association of the deportees of Convoy 77 would receive the sponsorship of the French Presidency which commissioned schools in France and abroad to research and reconstruct their lives in France and their last days. The project was to “put adolescents in charge not of a sepulchral memory but of the reconstitution of life paths more than death paths.”

The project was initiated by a class at the French Lyceum in Vilnius before the Covid-19 epidemic, under the direction of Professor Yvan Leclère, author of a book, Soviet Hegemony. These enthusiastic students began a search on the internet spanning several continents, lasting several years, to piece together why and how these eight Lithuanian Jews had gone to France, how they had lived there and how they came to become ensnared by the Nazis, and finally, sent to their death in Auschwitz. This book can be read as a journal — at times a thriller — that details, sometimes on a daily basis, what progress had been reached in discovering the whereabouts of the eight Lithuanian Jews and also of members of their families who had escaped capture by the Nazis or had been living abroad — and out of danger — at the time these eight were caught.

◊

In 2016, Chris Heath read an item in the New York Times about a tunnel that had been discovered “at a Holocaust killing site”. It was referring to Ponar near Vilna (Yiddish Ponár, Polish Ponary, today’s Paneriai outside Vilnius, capital city of Lithuania). It is around ten kilometers (six miles) southwest of Vilnius city center. This caught his attention and he decided to write a book about this heroic feat. The main title is borrowed from two lines that Shmerke Kaczerginski had written in his poem “Shtiler, Shtiler” (Quieter, quieter) that was put to music and sung in the Vilna Ghetto.

Ponar near Vilna (Yiddish Ponár, Polish Ponary, today’s Paneriai outside Vilnius, capital city of Lithuania). It is around ten kilometers (six miles) southwest of Vilnius city center. This caught his attention and he decided to write a book about this heroic feat. The main title is borrowed from two lines that Shmerke Kaczerginski had written in his poem “Shtiler, Shtiler” (Quieter, quieter) that was put to music and sung in the Vilna Ghetto.

Ponar: 100,000 persons killed by bullets from summer 1941 to spring of 1944, about 70% of them Jews including women, children, and the elderly.

Ponar: List of twelve escapees from Ponar who survived (April 1944): Josef Bielic, Abraham Blazer, Yitzhak Dogin, Yuli Farber, Shlomo Gol, David Kantorovich, Zalman Matzkin, Lejzer Owsiejczyk, Konstantin Potanin, Motke Zeidel, Adam Zinger, Peter Zinin

Simon Wiesenthal recounted that he escaped the threat of imminent death seven times as a slave and captive of the Nazis during World War II. Frida Michelson, a Latvian Jew from Riga, escaped an imminent death when on December 8, 1941, moments before she would have been ordered into a grave to be shot in Rumbula, she threw herself on the ground in the snow and pretended to be dead. She was saved by the fact that hundreds of pairs of shoes were piled on her body covering her from the eyes of the murderers, who did not discover her. Otherwise, she would not have told her story to David Silberman.[1]

I want to share with our readers a remarkable book with reproductions of paintings and drawings by and about David Olère who had been a member of a Sonderkommando in Auschwitz-Birkenau. But after the war he felt his mission was to bear witness to the truth, including the horrendous scenes he had seen and himself been part of: Vergessen oder Vergeben – Bilder aus der Todeszone by Alexandre Oler and David Olère [= David Oler]; zu Klampen! (Verlag- Springe/Deutschland; originally published in French in 1998 by his son Alexandre Oler: Un genocide en heritage.

Despite the millions of Jews killed by bullets or who died of beatings, pogroms, hunger or ill treatment in Poland and in the Republics of the USSR, the iconic symbols of Nazi evil remain, for a large segment of the world population, the gas chambers and crematories of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the five other extermination camps in Poland. Historians have stressed the fact that the Nazi killers and their helpers sometimes found those mass slaughters by bullets or asphyxiation inside trucks where monoxide of carbon had been injected to be too tedious and harsh to bear for the executioners. So, Nazi Germany switched to mass killings in gas chambers with Zyklon B and – concerned about leaving traces – devised the crematories. Searching for the roots of this industrialization process, Simon Wiesenthal had already come to that conclusion very early (as quoted by Guido Knopp in Die SS – Eine Warnung der Geschichte).

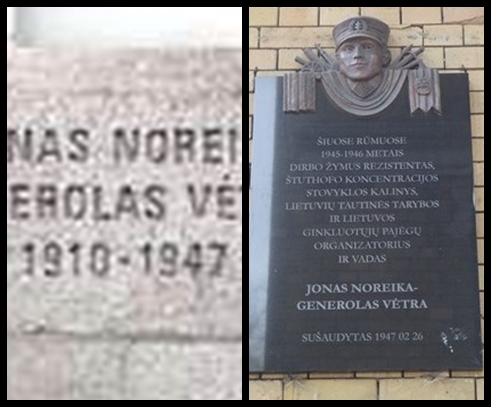

UPDATE OF JULY 2023: NOREIKA PLAQUE COMES DOWN FOR NATO CONFERENCE. FOR HOW LONG?

UPDATE OF JULY 2022: Foti’s The Nazi’s Granddaughter is reissued with the new title Storm in the Land of Rain

Sylvia Foti’s major new book is widely available in English and Lithuanian, among other languages. QUESTION: Why is the center of Vilnius still blighted by an upgraded plaque & bas-relief (right) and a central boulevard marble slab glorifying Hitler collaborator Jonas Noreika, who masterminded the death of thousands of Jews, and touted his unadulterated hate for Jewish fellow citizens in a prewar book? Why do Western diplomats, and most visiting American, British and Israeli Jewish dignitaries feel obliged to avoid even the most polite critique of these prominent carbuncles on the face of the European Union? Surely, a true friend of Lithuania would want the best for Lithuania and its international stature, even if a small far-right “history rewriting elite” might feel offended.

Sylvia Foti’s major new book is widely available in English and Lithuanian, among other languages. QUESTION: Why is the center of Vilnius still blighted by an upgraded plaque & bas-relief (right) and a central boulevard marble slab glorifying Hitler collaborator Jonas Noreika, who masterminded the death of thousands of Jews, and touted his unadulterated hate for Jewish fellow citizens in a prewar book? Why do Western diplomats, and most visiting American, British and Israeli Jewish dignitaries feel obliged to avoid even the most polite critique of these prominent carbuncles on the face of the European Union? Surely, a true friend of Lithuania would want the best for Lithuania and its international stature, even if a small far-right “history rewriting elite” might feel offended.

THE LATEST

Reviews of Bloodlands

Reviews of Black Earth

Instrumentalization?

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

This journal holds leading historian Professor Timothy Snyder (Yale University) in the highest esteem, and trusts that this select list of reviews taking issue with aspects of Bloodlands of direct concern to DefendingHistory.com will not be taken amiss. It does not include reviews which have engaged in personal attack or pursued grudges, or which focus on other issues.

This journal holds leading historian Professor Timothy Snyder (Yale University) in the highest esteem, and trusts that this select list of reviews taking issue with aspects of Bloodlands of direct concern to DefendingHistory.com will not be taken amiss. It does not include reviews which have engaged in personal attack or pursued grudges, or which focus on other issues.◊

Rabbi Dovid Kahana Spiro (1901-1970) was a very pious and learned man who cofounded the Jewish community in Fürth after the Holocaust. He worked there for twenty-five years as a community rabbi and helped numerous people in need. The Firter Rov (Fürther Rav) was buried in the Har Hamenuchos Cemetery in Jerusalem. A picture of his tombstone can be found in Moshe Rosenfeld’s recently published book on Rabbi Spiro. The book’s thirteen chapters cover in great detail the origins of the family Spiro, their pre-war life in Poland, the Warsaw Ghetto, survival, rebuilding, dialogue with a bishop, divorce cases and much more.

(Fürther Rav) was buried in the Har Hamenuchos Cemetery in Jerusalem. A picture of his tombstone can be found in Moshe Rosenfeld’s recently published book on Rabbi Spiro. The book’s thirteen chapters cover in great detail the origins of the family Spiro, their pre-war life in Poland, the Warsaw Ghetto, survival, rebuilding, dialogue with a bishop, divorce cases and much more.

The author, who now lives in London, grew up in Fürth and practically from birth had a close relationship with Rabbi Spiro, who lived next door. Rosenfeld’s mother was the rabbi’s cousin, and his father became his right-hand man. The author frankly admits that he should have asked a thousand questions at the time, but didn’t. And therefore there are many answers that he honestly does not know today. Nevertheless, with a vast amount of work and love, he managed to collect a wealth of material and to publish this extensive work. The history of the Spiro family, that lived in Poland, is presented in great detail.

◊

My good friend and colleague for two and a half years in Vilnius, Dónal Denham, has written a book with the title Nine Lives: The Reflections of a Dedicated Diplomat . The book is an interesting, fascinating read about an eventful career in the service of Ireland at home and abroad, enriched by an excellent selection of photos that add life and substance to the text. The author also draws a vivid picture of his early formative years in Ireland and England and student years at Trinity College. He writes warmly about his family, not avoiding the pain of personal losses, exacerbated by separation and distance. Diplomats from all countries would subscribe to his tribute to his wife Siobhan (“without whom nothing worthwhile would have happened to me”) who “as an unpaid ‘trailing spouse’ was a treasure beyond measure, largely unrecognized by officialdom.”

. The book is an interesting, fascinating read about an eventful career in the service of Ireland at home and abroad, enriched by an excellent selection of photos that add life and substance to the text. The author also draws a vivid picture of his early formative years in Ireland and England and student years at Trinity College. He writes warmly about his family, not avoiding the pain of personal losses, exacerbated by separation and distance. Diplomats from all countries would subscribe to his tribute to his wife Siobhan (“without whom nothing worthwhile would have happened to me”) who “as an unpaid ‘trailing spouse’ was a treasure beyond measure, largely unrecognized by officialdom.”

So, which are Dónal Denham’s nine diplomatic lives?

◊

◊

Arūnas Bubnys’s book The Holocaust in the Lithuanian Provinces (Holokaustas Lietuvos provincijoje, Margi raštai, Vilnius, 2021) is another publication of the International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania (ICECNSORL). Up until now, books published by the Commission were academically written and appreciated by a sophisticated readership. Moreover, they were always published in both Lithuanian and English. This book is different. It is available only in Lithuanian. Previously published monographs would also include Commission-approved conclusions; this book has no such thing. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the Commission’s academics did not discuss the book among themselves before its publication. But let’s start at the beginning.

raštai, Vilnius, 2021) is another publication of the International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania (ICECNSORL). Up until now, books published by the Commission were academically written and appreciated by a sophisticated readership. Moreover, they were always published in both Lithuanian and English. This book is different. It is available only in Lithuanian. Previously published monographs would also include Commission-approved conclusions; this book has no such thing. As far as I have been able to ascertain, the Commission’s academics did not discuss the book among themselves before its publication. But let’s start at the beginning.

The book is geographically quite extensive: 23 counties and 140 towns are cited. This is really a lot, but it is also quite obvious that the coverage of towns in different counties is unequal. When it comes to Šilutė county in western Lithuania, for example, several camps and fates of individual Jews are mentioned in passing, but no single town is described. For the Marijampolė county, only the fate of the Jews of Marijampolė itself is presented. Šiauliai xounty (15 towns) and Alytus County (12 towns) are the most extensively covered.

◊

◊

Under the Nazis the Jews had not the right to live. Under the Soviets they had not the right to publicly commemorate the victims of the Holocaust as Jews. In the Baltic States the fate of the Jews during World War II had not only been harsh, it had led to over 95% of their population being killed in front of open pits, in the ghettos, in work details, in camps, by bullets, beatings, hunger, exhaustion through work, or by mere sadistic arbitrary acts of killing.

In the sixties, some Jewish activists living in Latvia, mostly in Riga, became interested in recording the history of the Holocaust in their native country by interviewing survivors and preserving the memory of what happened during these terrible times. They had to act secretly because the Soviet authorities and the KGB frowned upon Soviet citizens who considered themselves Jews as well as Soviet citizens.

VILNIUS—As ever, debates on the Holocaust in Lithuania take on their own drama, a drama never far from the ongoing alleged revisionism by Baltic governments, not least about the outbreak of local violence, plunder and murder of defenseless Jewish citizens by local “patriots” still glorified as “anti-Soviet heroes” for their unleashing of the Holocaust locally in the first days following the launch of Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. In the Baltics as in (western) Ukraine, thousands of Jews were victimized and killed before the first German soldiers set foot on, or set up their administration in the territories. Far from fleeing some local “rebellion” as mendaciously claimed by state museums and commissions, the Soviet army was fleeing Hitler’s invasion — the largest invasion in human history.

◊

◊

The Vilna Yiddish Reading Circle, now in its twentieth year and open to all, announced today that its weekly session on Wednesday evening 20 February (as usual, from 6 PM sharp at the Vilnius Jewish Community at Mesiniu 3 in Vilnius Old Town) would be dedicated to the just-published handsome book of essays, articles and memoirs by the beloved Yiddish (and Lithuanian language) journalist Aaron Garon (1919−2009). The book, Di yídishe velt fun Vílne (The Jewish World of Vilna) is a collection of some of his Yiddish prose (essays and memoirs) with full Lithuanian translation, published in avant-garde vertical format, designed by the prominent young book-design maestro Greg Zundelovitch. It was brought out by the author’s children, longtime Israeli residents Tamara and Evgeni Garon, thanks to support from the Lithuanian government’s Good Will Foundation.

◊

◊

Latvia’s Minister for Foreign Affairs Edgars Rinkēvičs seems to have found a brand new idol and role model — Ludwig Seya, who had been a diplomat in the prewar Latvian Republic for 22 years. For a short time he was a minister, but mostly he held ambassadorships to various countries. After Latvia was annexed to the Soviet Union he taught at the main Latvian university in Riga. In 1944 he was arrested by the Nazis for underground activities in the Latvian Central Council, a union of pre-war politicians and intellectuals who tried to persuade the West to insist on the independence of Latvia after World War II. After being liberated from the concentration camp on the territory of Poland, Seya was arrested by the Soviet military authorities and sent to a Stalinist gulag.

As anyone who has been following events in Lithuania for the last several years surely knows by now, the country sports street names and monuments honoring locals who collaborated with the Nazis during World War Two. It was in this context that I attended an event in Washington, DC yesterday at the Wilson Center’s Kennan Institute discussing Ruta Vanagaite’s controversial book “Our People” (it appeared in Lithuanian in 2016) that blows open the door describing the true extent of Lithuanian collaboration in the Holocaust. Vanagaite and her co-author Efraim Zuroff , director of the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Israel Office, spoke at the event.

[updated]

See DH’s BOOKS SECTION

◊

BERLIN—As the first issue of Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism (JCA) rolled off the presses this week, there was widespread hope that the field of Antisemitism Studies, particularly in Europe, had achieved a notable and reinvigorating breakthrough. What with the entanglements of “larger politics,” both anti-Israel politics in Western Europe, and Holocaust-revisionist politics in Eastern Europe, and right in the midst of populist movement ascendancy and the new east-west Cold War with Putin’s dictatorial and dangerous Russia, the field has long been stymied in Europe. One major factor has been the unhelpful attitude of some of the major European institutions (and at times, even Western embassies in Eastern Europe and major Western organizations) that have covered for antisemitism by arranging “staged” events that cover up for the current issues rather than address them. Finally there is a journal whose inaugural issue’s message from the editor makes clear that it will break the lame taboos of recent years in the field.

◊

VILNIUS—As the first small shipment of Harvard Library’s new book, Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library arrived this week in the Lithuanian capital, there was widespread satisfaction that at least a tabulation of the contents of Leyzer Ran’s extensive archive of Jewish Vilna is finally available. The collection was bequeathed to Harvard University where the Library maintains it as a distinct entity with its own name, space, and now, a handsome catalogue brought out by Harvard University. Leyzer Ran (1912-1995) is widely considered to be the primary postwar chronicler of the centuries-old unique Jewish civilization of the city known in Yiddish as Vílne, Yerusholáyim d’Líte — Vilna, Jerusalem of Lithuania. The newly appeared catalogue was compiled and edited by Dr. Charles Berlin, who is Head of Judaica at Harvard Library and Harvard University’s Lee M. Friedman Bibliographer in Judaica.

VILNIUS—As the first small shipment of Harvard Library’s new book, Catalog of the Leyzer Ran Collection in the Harvard College Library arrived this week in the Lithuanian capital, there was widespread satisfaction that at least a tabulation of the contents of Leyzer Ran’s extensive archive of Jewish Vilna is finally available. The collection was bequeathed to Harvard University where the Library maintains it as a distinct entity with its own name, space, and now, a handsome catalogue brought out by Harvard University. Leyzer Ran (1912-1995) is widely considered to be the primary postwar chronicler of the centuries-old unique Jewish civilization of the city known in Yiddish as Vílne, Yerusholáyim d’Líte — Vilna, Jerusalem of Lithuania. The newly appeared catalogue was compiled and edited by Dr. Charles Berlin, who is Head of Judaica at Harvard Library and Harvard University’s Lee M. Friedman Bibliographer in Judaica.

◊

◊

◊

What makes Rūta Vanagaitė’s Ours (Mūsiškiai) very different from all other Lithuanian books on the Holocaust is that it was from the start written as a bestseller. Written by an experienced public relations professional as an appeal to the Lithuanian public, the book raises the painful issue of historical responsibility. The author does not refrain from giving a personal twist to the story (it would be impossible otherwise, as the Holocaust is an issue of individual position and individual responsibility). The author is piercingly direct and uses black comedy. She approaches the topic with composure and a sense of supremacy. These two features may irritate the reader. However, she is entitled to it as she aims to confront the reader, which she so eloquently achieves.