BOOKS | EVENTS | YIDDISH AFFAIRS | VILNIUS JEWISH COMMUNITY

◊

by Dovid Katz

◊

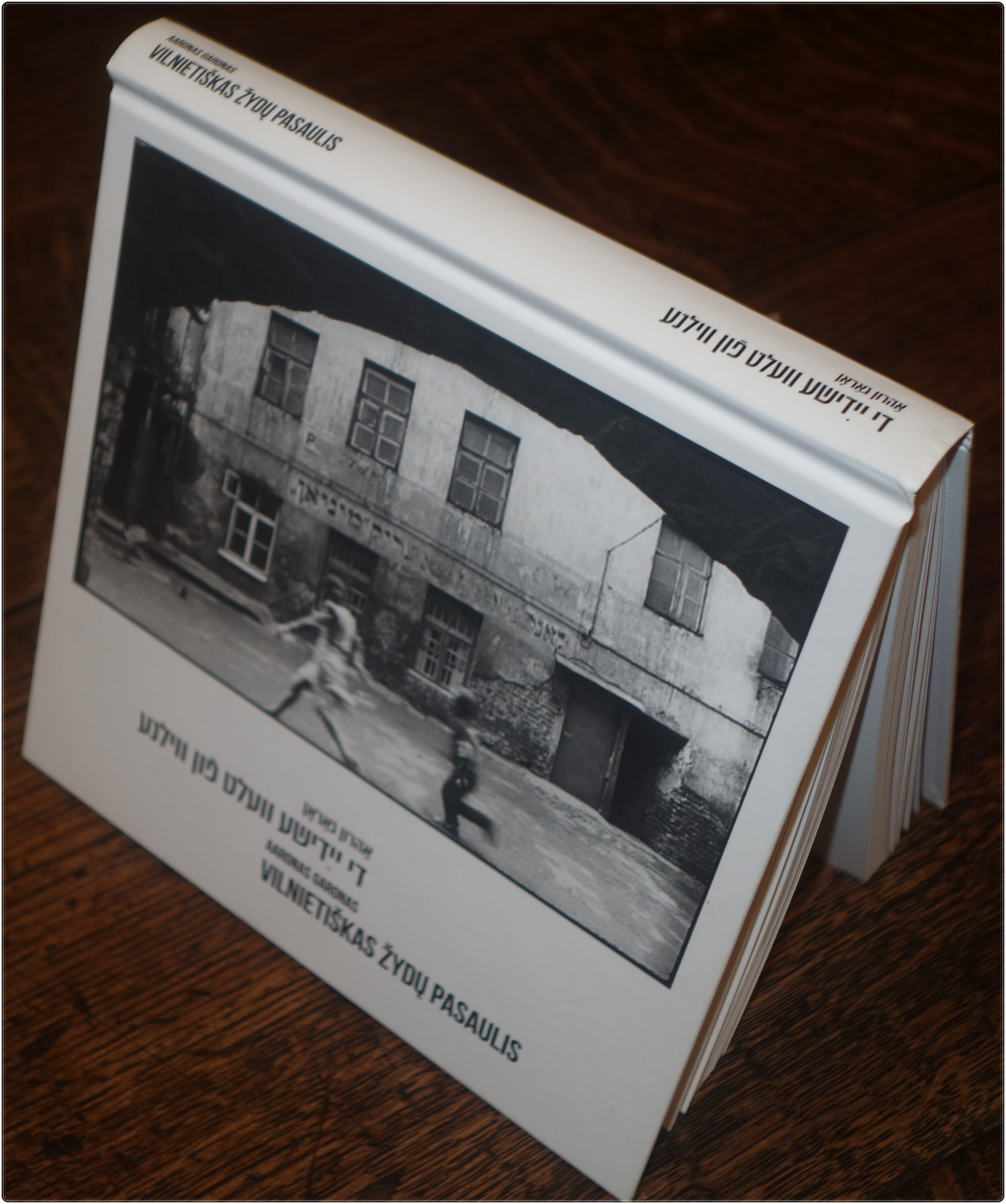

The Vilna Yiddish Reading Circle, now in its twentieth year and open to all, announced today that its weekly session on Wednesday evening 20 February (as usual, from 6 PM sharp at the Vilnius Jewish Community at Mesiniu 3 in Vilnius Old Town) would be dedicated to the just-published handsome book of essays, articles and memoirs by the beloved Yiddish (and Lithuanian language) journalist Aaron Garon (1919−2009). The book, Di yídishe velt fun Vílne (The Jewish World of Vilna) is a collection of some of his Yiddish prose (essays and memoirs) with full Lithuanian translation, published in avant-garde vertical format, designed by the prominent young book-design maestro Greg Zundelovitch. It was brought out by the author’s children, longtime Israeli residents Tamara and Evgeni Garon, thanks to support from the Lithuanian government’s Good Will Foundation.

The new bilingual edition of selected essays and memoirs by Aaron Garon (1919-2009) comprising the original Yiddish and a full Lithuanian translation. The book was designed by Greg Zundelovitch and published by the author’s children in Israel with support from the Good Will Foundation in Vilnius. A number of events are scheduled this month to mark its appearance.

The new bilingual edition of selected essays and memoirs by Aaron Garon (1919-2009) comprising the original Yiddish and a full Lithuanian translation. The book was designed by Greg Zundelovitch and published by the author’s children in Israel with support from the Good Will Foundation in Vilnius. A number of events are scheduled this month to mark its appearance.

◊

Some aspects of Garon’s biography are characteristic of his time and place. He came from a traditional but broad-minded Jewish family and went on in his youth to become a radical journalist and author, espousing ideals of socialism, equality of all people and a just society. During World War II, he fought heroically in the war against Hitler, serving with valor in the Red Army’s 16th Division (also known as the “Lithuanian Division” and informally, with some humor, as the “Jewish division” because of the high percentage of Jewish soldiers in its ranks). Garon was duly credited in the Jewish Museum’s room dedicated to anti-Nazi veterans, and hopefully that extraordinary exhibit will again be made available to the public.

One aspect of Garon’s life is however perhaps unique among Vilna Yiddish authors. Though born and bred in Vilna (Wilno in the interwar Polish Republic), he spent a number of critical years of his youth in prewar Kaunas (Yiddish Kóvne), then de facto capital of the Republic of Lithuania. The border between the two countries was one of the hardest in Europe between the wars, and there was minimal daily cultural interaction. Unlike virtually all the other Vilna Yiddish writers of his generation, Garon was fluent in Lithuanian and indeed became a Lithuanian editor after the war. Aside from Garon, all the other Yiddish journalists and writers were either of the rarefied Vilna milieu and non-Lithuanian speaking, or from the interwar republic and Lithuanian speaking. This set him apart from the other Vílner in town as the Soviet Union’s autocratic rule was collapsing in the late 1980s.

After the war, Garon completed a law degree in Vilnius but preferred journalism and became a prominent editor in Soviet Lithuania of Lithuanian language publications. Throughout his life, he was known for his sharp Litvak wit, love of friendly argument (which he always delivered with a streak of singular flamboyance), care for others, and an uncanny ability, again in the Litvak spirit of old, to “argue the other side” in a conversation pointing out how differently one can look at the same set of phenomena.

When the repressive Soviet regime began to crumble in the late 1980s, Garon was quick to return to Yiddish and to put his heart and soul into writing for (and helping with the production and proofing of) Yerusholáyim d’Líte, the incredible Lithuanian Jewish community newspaper that appeared from 1989 until 2011 in four languages (English, Lithuanian, Russian, and Yiddish). It is for many a grave disappointment that nearly all its issues, in all four languages, continue to remain unavailable online (Defending History has brought out a small sampling from its later years). Hopefully this will be rapidly remedied by the resources of the Good Will Foundation or others in the interests of preserving one of the prime historic achievements of the Lithuanian Jewish community in the years since the rise of modern democratic Lithuania. In sharp contrast to the “dead Jew business” in service to nationalist PR or history revisionism, this amazing newspaper presented a diversity of views of the real, living, vibrant and free Jewish people of Lithuania who felt fully able, on its pages, to enjoy the freedoms guaranteed by the Lithuanian constitution and the European Union, not least the freedom to debate.

Garon and his family relocated to Israel in 1992, where he became active in Yiddish writers’ circles and worked as editor for various books and periodicals. He could be found every Friday morning at the Yiddish writers’ weekly meeting at Leivick House on Tel Aviv’s Dov Hoz Street. Like many Yiddish writers from the former USSR, Garon faced a wide diversity of linguistic issues in switching to Western norms of Yiddish spelling, vocabulary, syntax, and stylistics more generally, when joining the international and Israeli centers of 1990s Yiddish literature. He became fascinated by the debate over purism vs. variationism, and descriptivism vs. normativism, that was raging in some New York Yiddish magazines between the two camps in the field (disclosure: I was leading the variationist-descriptivist camp in some of those debates). Garon wrote one of his most exotic Yiddish pieces, in Itche Goldberg’s splendid magazine Yidishe kultúr, bringing to Yiddish readers parallels from nineteenth and twentieth century Lithuanian language debates between purists and descriptivists (citing for example, decisions on words for “umbrella” and “suspenders”). Unfortunately, the editors did not include it in the present collection, but that can be taken as an omen for further collection of his Yiddish work beyond the new volume, perhaps online, in the future, that would also preserve samples of his work in Yiddish from before the war, “politically incorrect” as they may be in today’s Eastern Europe. In fact a massive new website featuring the actual works of Lithuanian Yiddish writers would be a huge contribution to the field.

Nevertheless, Garon continued his close contact with Yerusholáyim d’Lite from Israel in close cooperation with the newspaper’s editor and key writer over its last dozen years, Milan Chersonski, who will hopefully be a keynote speaker at some of the various book launching events (known locally as “presentations”) planned for later this month. Chersonski, who went on to become a Defending History staff writer when his newspaper was closed down, is the person in modern Vilnius best able to do justice to the Yiddish legacy of Aaron Garon.

◊

In 1990, I had the extraordinary good luck — and pleasure — to discover Aaron Garon for the Western world of Yiddish literature and culture. It happened during the early days of my first visit to Vilnius in Dec. 1990 (dedicated to an academic project to enable Lithuanian students to study at Oxford). Knowing nobody in town, I took advice from the then (pre-independence) Lithuanian Legation in London’s director, Romas Kinka, who found me a terrific family to stay with, that of Sofija Vienožinskienė on Antakalnis Street. When she learned that I was head of the Yiddish program at Oxford University she said: “This must be an act of God, my neighbor in the next building is a famous Yiddish writer, Aronas Garonas, come, let’s go and find him!”

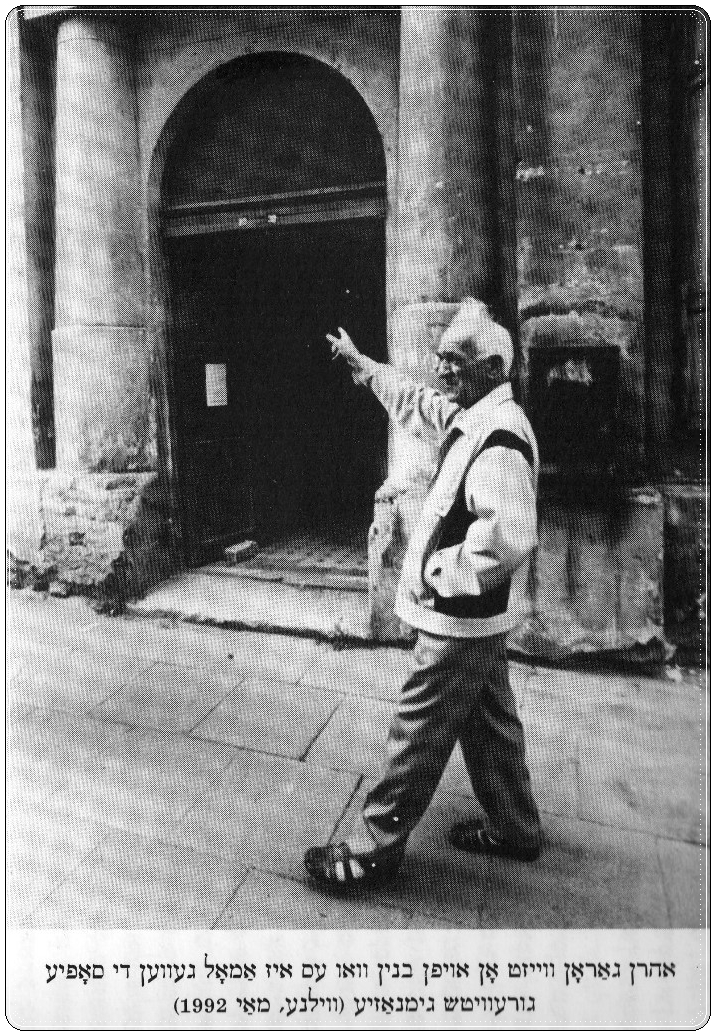

In May 1992, when Aaron Garon was at work on his historic memoir of Sofye Gurevitsh’s Vilna Yiddish academy, the Oxford Yiddish team arranged for Vilnius photographer Paulius Lileikis to accompany him on a return visit to the building, by then (as now) an apartment house. It is on a corner of Makóve (today’s Aguonų gatvę). PHOTO: Paulius Lileikis for Oxford Yiddish 3 (Oxford 1995), p. 161.

◊

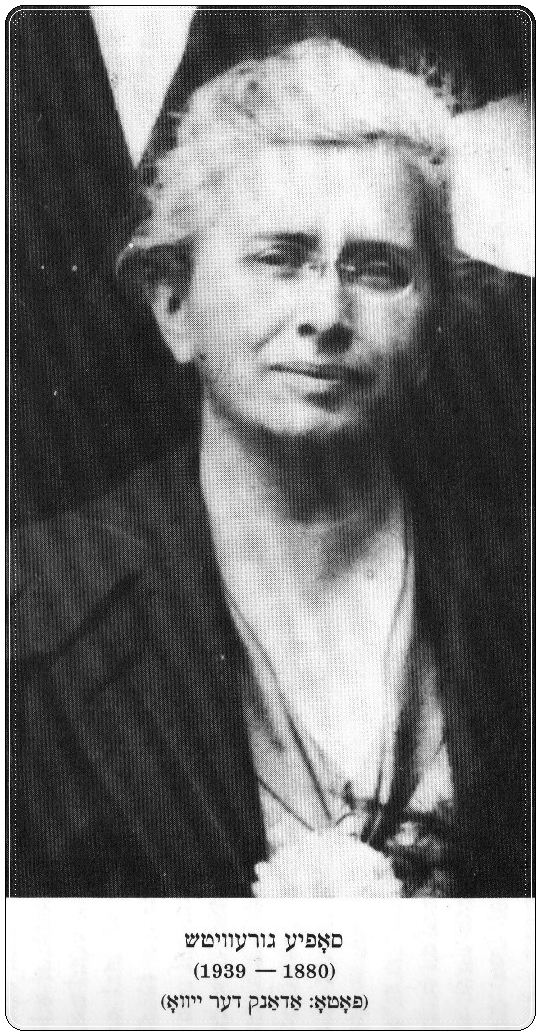

I began during my rapidly evolving friendship with Garon and his dynamic family and circle of friends to start pestering him about the need to write memoirs of his prewar Jewish life in Vílne and Kóvne. We were then planning the third volume of the Oxford Yiddish series, that appeared entirely in Yiddish. We agreed on the topic that was closest to his heart: the amazing Yiddish educational institution where he had studied, and the amazing woman who led and founded it. His memoir, “Sófye Gurévitsh un ir vílner gimnázye” (Sofia Gurevich and her Vilna Academy), was published in Oxford Yiddish 3 (Oxford 1995, pp. 153-168). In some ways, it forms the heart and soul of the new Garon collection (pp. 40-64), as famed Lithuanian Jewish author Grigory Kanovich notes in his preface to the new Garon collection (p 11), calling these “its best pages”. In the new book, the memoir is adorned with rare additional pictures added from Fania Yocheles Brantsovsky’s rich personal collection. Named by popular acclaim for its inspirational leader and one of the most important women in the history of Jewish Vilna, the Sofye Gurevitsh Gimnazye (Sofia Gurevich Academy) produced, alongside Aaron Gardon, a host of people who would go on to do great things for Yiddish and Jewish culture in different parts of the world in the decades to come. They include the late Prof. Benjamin Harshav (Hrushovski) of Yale University, and the late artist and author Yonia Fain of New York. In Vilnius today, the beloved Yiddish librarian and Holocaust educator Fania Yocheles Brantsovsky, an extraordinary veteran of the Jewish partisan resistance to the Nazis during the Holocaust, is likewise a proud graduate of the same Vilna academy of Sofia Markovna Gurevich.

Sofia Markovna Gurevich (1880−1939). Photo: Yivo Institute for Jewish Research (New York).

◊

Many books end up having “internal histories” of their own. After an initial dismally botched translation provided by a fake, PR-driven “Yiddish institute” in town, the entire project was verily rescued by the eminent Lithuanian editor, essayist, humanist and Holocaust educator Linas Vildžiūnas. He invested months to meticulously research hundreds of points in the Lithuanian text, many of which are specific to Jewish culture. An old and trusted friend of the Garon family over decades, Vildžiūnas is this book’s white knight.

◊

The Vilna Yiddish Reading Circle, founded in 1999, is where Yiddish literature is studied and discussed in Yiddish, where Yiddish is the genuine language of speaking, reading and learning, not a political tsátske for nationalist PR and “slam-damn Jewish politics”. Wednesday evenings from 6 PM at the Vilnius Jewish Community at Mesiniu 3 in Vilnius Old Town.

EVERYONE WELCOME!