OPINION | ARTS | BOOKS | HISTORY | POLITICS OF MEMORY

◊

by Roland Binet (De Panne, Belgium)

◊

I want to share with our readers a remarkable book with reproductions of paintings and drawings by and about David Olère who had been a member of a Sonderkommando in Auschwitz-Birkenau. But after the war he felt his mission was to bear witness to the truth, including the horrendous scenes he had seen and himself been part of: Vergessen oder Vergeben – Bilder aus der Todeszone by Alexandre Oler and David Olère [= David Oler]; zu Klampen! (Verlag- Springe/Deutschland; originally published in French in 1998 by his son Alexandre Oler: Un genocide en heritage.

Despite the millions of Jews killed by bullets or who died of beatings, pogroms, hunger or ill treatment in Poland and in the Republics of the USSR, the iconic symbols of Nazi evil remain, for a large segment of the world population, the gas chambers and crematories of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the five other extermination camps in Poland. Historians have stressed the fact that the Nazi killers and their helpers sometimes found those mass slaughters by bullets or asphyxiation inside trucks where monoxide of carbon had been injected to be too tedious and harsh to bear for the executioners. So, Nazi Germany switched to mass killings in gas chambers with Zyklon B and – concerned about leaving traces – devised the crematories. Searching for the roots of this industrialization process, Simon Wiesenthal had already come to that conclusion very early (as quoted by Guido Knopp in Die SS – Eine Warnung der Geschichte).

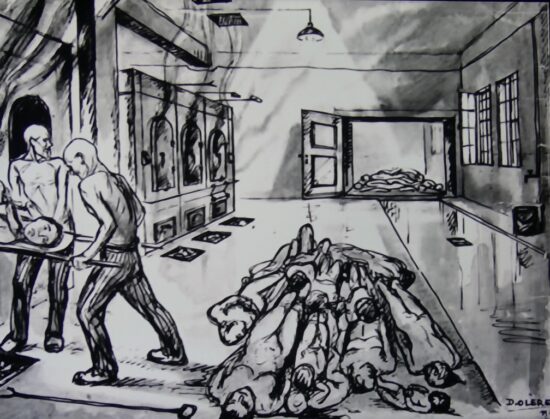

Members of the Sonderkommandos had been the ones put in charge of being present when the death trains arrived, then of taking the corpses from the gas chambers and cleaning them afterwards; transporting the corpses to the crematories after having searched the corpses for valuables; taken the gold teeth and cut the hair of the women. Few survived among these “Himmelfahrtkommandos” as they were usually themselves killed after a period of between three and six months, so that they could not themselves later on bear witness. Let us cite Schlomo Venezia and Filip Müller, as well as the anonymous collective masterwork Des Voix sous la Cendre (Voices under the Ashes). There has also been a film that depicts in a very harsh and raw – almost violent – way the reality of the emptying of gas chambers: Son of Saul, a Hungarian film by László Nemes (2015).

David Olère (Oler) (1902-1985) was a Polish Jew living in France where he had been arrested in 1943 during a raid that targeted local Jews, and later deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was assigned to a Sonderkommando but thanks to his knowledge of many languages and chiefly his talent for drawing and painting, he survived the Holocaust; although like many of his fellow members he, too, had had to be present when the death trains arrived to accompany the Jews to the gas chambers, empty them of the corpses and burn them in the crematories.

In the Crematorium. By David Olère. In Ghetto Fighter’s House, Israel.

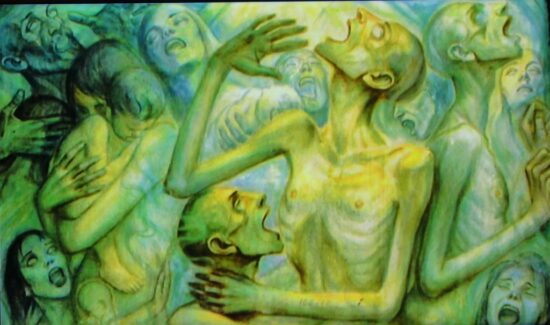

After his liberation, David Olère, over a long period of time, created a series of drawings and paintings of what he had seen and experienced but in a very realism-conceived style for the harsh and the raw.

As Serge and Beate Klarsfeld stated in the introduction to Vergessen oder Vergeben (Un genocide en héritage): “David Olère, the only painter in the world who saw and survived it all, had not received the recognition as an artist that he deserved, whereas others, who had not seen anything, received acclaim from the public. The public sought beauty and transparency. He drew from his memory and was only in search of the truth. For the others what was aesthetic was in the forefront. For him it was moral commitment.”

The Klarsfelds also made it possible for four paintings and nearly forty drawings by David Olère to be donated to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, and some eighteen paintings to be given to the the Jewish Heritage Museum in New York City. Let these collections be visited and appreciated for generations. They uniquely put in the forefront of our thoughts and remembrance not the aesthetic and abstract renditions of the Holocaust but rather the harsh, sordid and bloody reality that the survivors and witnesses of the Nazi crimes have seen and lived through. For these are the works that enable us to truly fathom the unfathomable that did transpire.

To end this tribute not only to a survivor of the Holocaust but also a truly great artist let me quote a poem by his son Alexandre Oler. It is a statement of what this survivor’s legacy means and should endure to mean in the future. I think it could even be a kind of motto for the present and coming generations for genuine remembrance of the Holocaust.

Forget or Forgive

- When you can forget the Evil

- Forget

- But forget only the Evil

- That was inflicted on you.

- When you wish to forgive the Evil

- Forgive

- But forgive only the Evil

- That you yourself suffered.

- Forget or forgive

- My son

- Forget and forgive

- But not in my name.

- Because to me, my Friends

- I regret but —

- From the victims I have received no task

- Other than to bear witness.

— Alexandre Oler