B O O K S

by Geoff Vasil

See also: Andriukaitis’s 2012 reply to the foreign minister; on the floor of parliament; Andriukaitis section

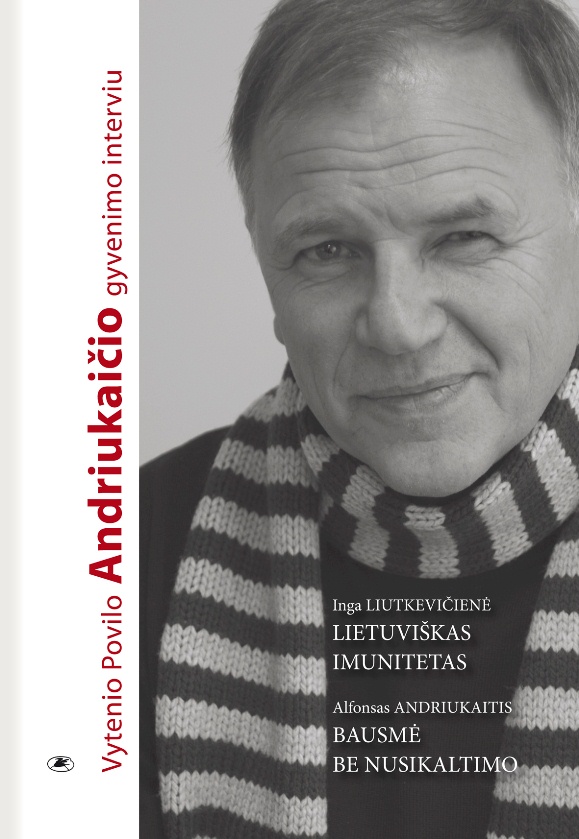

Vytenis Povilas Andrukaitis, health minister of Lithuania. Photo: DefendingHistory.com

Vytenis Andriukaitis is a veteran politician. If you haven’t been following Lithuanian politics since 1990, there’s a good chance you’ve never heard of him, and even if you have, there’s a fair chance you didn’t notice him amid the various cults of personality which have dominated the political scene since about 1990.

The reason for that is fairly simple: Andriukaitis has never cultivated or even tolerated a cult of personality to grow up around him. From the very first days of Lithuanian independence, a freedom movement with which Andriukaitis was intimately involved, he has stubbornly clung to the idea of multiparty parliamentary democracy, largely by his own tenacity reviving the pre-World War II Lithuanian Social Democratic Party.

In early 2012 Andriukaitis gained some media attention — his opponents would say notoriety — when he, some other members of his party and politicians across Europe signed on to a historic declaration condemning Holocaust revisionism at the European level. The document, the Seventy Years Declaration (SYD), was made public on the seventieth anniversary of the Wannsee conference in Berlin, where the Nazi plan for the Final Solution was mooted to the lower echelons of power in the Third Reich and made explicit. The SYD, which has had its own complex history in the year and a half since it was released, was an explicit reply to the 2008 Prague Declaration.

Although the tone of the declaration is somber, sober and fairly uncontroversial on the face of it, Andriukaitis was attacked publicly by then-Lithuanian foreign minister Audronius Ažubalis as almost a traitor to the Lithuanian state, the vanguard of an attempt to rewrite Lithuanian history to rehabilitate the Soviet occupation of Lithuania after World War II. Andriukaitis responded publicly, calling the Lithuanian government’s policy of attempting to foist an obfuscationist revisionist version of the Holocaust on Europe that of a small group of right-wing politicians, not the policy of the state, neither the policy of his party. Ažubalis fumed that Andriukaitis was calling Vaclav Havel a misguided signatory to the so-called Prague Declaration calling for Stalinist crimes to gain equal status with the Holocaust at the EU level, as a cheap pre-election trick. In the event, the conservatives were voted out, but for whatever reason, Vytenis Andriukaitis did not become Lithuania’s new foreign minister, despite the earlier announcement by his party that he would assume that post in the event of victory… Incidentally, Andriukaitis’s public stand won him rapid congratulations in 2012 from British MP Denis MacShane and former JDC official Andres Spokoiny, among others.

Later in 2012, Andriukaitis, and fellow Social Democratic MP Algirdas Sysas were the lone challengers to the government’s decision to rebury with full honors and a panoply of glittering events the remains of 1941 Hitlerist puppet prime minsiter Juozas Ambrazevicius (Brazaitris). Andriukaitis boldly challenged the foreign minister on the floor of the Seimas.

◊

A little while after the conservatives’ public furore over the Seventy Years’ Declaration had died down, an interesting book appeared in the shops throughout Lithuania. It features a black and white photograph of a smiling Andriukaitis, framed by several different titles. The largest title runs vertically up the left side, with two others in the usual horizontal orientation tucked in under Andriukaitis’s striped muffler. The book itself is large, maybe dauntingly large.

The preface tells the reader it is actually four books in one: “Footprints in Time” about the Andriukaitis family from Tsarist times to the present; a “Life Interview” (the main title on the cover) conducted with Andriukaitis by a Lithuanian journalist, carrying the subtitle “Lithuanian Immunity,” which is the largest section by far; followed by a series of brief recollections of Andriukaitis by like-minded colleagues and ending with a complete, if short, book by Andriukaitis’s late father Alfonsas called “Punishment without Crime,” seemingly a play on the name of Dostoyevsky’s “Crime and Punishment.”

As far as I can tell, almost no one has reviewed the book in Lithuanian! No English or Russian translation exists, which is a shame, because the biographical section sheds new light upon the inner workings of the Lithuanian independence movement in the years before and after de facto Lithuanian independence—in late 1991, when Russian president Boris Yeltsin formally recognized the state. Perhaps it is exactly because of these insights that the book has gone unreviewed and, for all practical intents and purposes, has been black-listed.

The biographical section, or “Life Interview,” is a conversation between Andriukaitis and Lithuanian journalist Inga Liutkevičienė held over the course of a year and a half. It takes the form of questions and answers, although not all of the questions are answered, and at times Andriukaitis goes well beyond the scope of the question. This section of the book is roughly 550 pages long, and flows naturally and chronologically out of the first part of the book, “Footprints in Time,” which details what happened to the family before Andriukaitis was born, with a cameo appearance by Lenin himself as members of the family sojourned in revolutionary Russia, leading up to their exile in Yakutia, where Vytenis was born. The family returned to Lithuania when Vytenis was already a young boy, in 1957. He tells an amusing story about how he and his brother stole away with some potatoes, a food they had only heard about up till then, and ate them raw, thinking it a fine feast.

His life in Lithuania is marked by ups and downs in his educational and professional career, until he ends up under the scrutiny of Soviet security in the 1970s for anti-Soviet activities. He seems to have been uniquely prepared for Lithuanian independence by the wisdom of his father, who foresaw the eventual ultimate collapse of the Soviet Union just around the time it actually did go through its death throes.

◊

Vytenis Andriukaitis had already decided upon social democracy as his model of choice for an independent Lithuania before most people in Lithuania even took the idea of independence seriously, and had done serious research on his chosen model as it was applied in Scandinavia and other European states.

When independence was declared—or reiterated—in March of 1990, with Andriukaitis as a signatory, he did something quite unusual. Instead of forming a new social democratic party to contest elections in what was now no longer the Supreme Soviet but the Seimas of the Republic of Lithuania, Andriukaitis thought it a better course to make contact with surviving members of the pre-World War II Lithuanian Social Democratic Party living in exile abroad and resurrect that body instead, even while recognizing the newly-independent Lithuanian state was not the same state which had disappeared from the map in 1940, neither in terms of its territory nor its form of government, which had been that of the autocratic Smetona.

A little later on, in the course of historic events cascading over the new Lithuanian state, Andriukaitis came up with the idea of inviting pre-World War II Lithuanian diplomat-in-exile Stasys Lazoraitis to contest elections for president, an initiative quickly coopted by what Andriukaitis deems “radicals” within the Sajudis independence movement, the nucleus of the future Conservative/Homeland Union Party, and ultimately ruined because of the latter’s public support.

◊

This is where the book gets extremely interesting, and serves as explanation for its seeming suppression inside Lithuania.

While he never seems to be engaging in sour grapes, and, quite to the contrary, actually seems to be omitting a great deal—one gets the sense his personal sense of ethics and morality is akin to that of the now almost-extinct Polish or Russian aristocracy of a hundred years ago—Andriukaitis tells the truth about what he saw in the early days of independence, inside the parliament, inside the movement. It’s not a pretty picture, for the most part. Machiavellian intrigues, xenophobia and a complete lack of ability to discern political reality mark the rise of Vytautas Landsbergis and his cronies, followed by a period which I personally remember when there was perceived to be a KGB agent lurking behind every corner and the thrill of the witch-hunt was intentionally cultivated by the conservatives and Christian Democrats.

Andriukaitis presents the facts as he knows them, never vindictively, almost always with reference to sources and people who can confirm their veracity. He takes special exception to those who wield the KGB boogeyman while they themselves have a more or less clear record of either working for or at least informing for that same KGB during the Soviet period. He also decries the hypocrisy of attempt by these same “radicals” who emerged out of the independence movement to rewrite history, to delegitimize the entire period of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, a period spanning fifty years during which an entire generation was born and died, as an illegal dark age of foreign occupation.

Andriukaitis argues that while the Soviet Lithuanian state was illegitimate, it was legal, and life carried on, people for the most part pursued their careers and lives and adapted to the Soviet system. There were very few real dissidents in the Lithuanian independence movement, Andriukaitis notes (and he should know, since he was for all practical purposes one of them), whereas many of those who later adopted the staunchest anti-Soviet anti-Communist positions had themselves gone along to get along, and had enjoyed the benefits of the Soviet system.

While he doesn’t make any categorical conclusions about the post-war partisans, preferring the idea they were a mixed bag, a motley crew of people with different motivations, he does condemn attempts by the Lithuanian right-wing and ultranationalists to paint them exclusively in glowing colors, noting there were common and war criminals among them, and Holocaust perpetrators, and many of the Lithuanian partisans engaged in atrocities against Lithuanian civilians on the flimsiest of pretexts, including hearsay accusations of “collaboration” with the by then firmly established Soviet regime.

Andriukaitis’s refusal to countenance the rewriting of history extends, of course, to the Holocaust in Lithuania as well.

He invites the proponents of the double genocide approach—Lithuanians who say Lithuanians killed Jews because Soviet Jews killed Lithuanians—to visit Auschwitz, which he has done, and to point to any Soviet camp or gulag which even approaches the barbarity the Nazis practiced against the Jews. Andriukaitis appears to have thought deeply about the Holocaust and to have visited the killing sites himself, and while he might have some of the details a little off, his general take is that the Holocaust was a unique instance of barbarity and anti-civilization in the history of mankind, and that the Nazis perfected a system of industrialized mass murder.

In other words, Andriukaitis adheres to the accepted version of history, unlike many of his Lithuanian colleagues. He also accepts the role of the Soviet Union as necessary liberator in the Allied fight against the death of civilization propagated by Hitler’s Third Reich, and talks about the positive contribution of the Lithuanian 16th Division within the Red Army, with fond memories of a friendship he maintained with a member of that division.

At one point, Andriukaitis comes right out with it and says the attempts to rewrite the history of the Lithuanian Holocaust are probably predicated on aspirations to force Russia to make reparations for Soviet damages inflicted on Lithuania. He points out it was Russia who first among the countries of the world recognized Lithuania in 1918 and in 1991, and doubts Russia is somehow legally liable as some sort of successor state to the Soviet Union.

There is a legal paradox at work here, Andriukaitis points out, because if today’s Lithuania is the successor state to the Lithuania of 1918-1940, then treaties undertaken then are still in effect, so that Vilnius belongs to Poland and Klaipeda/Memel to Germany, among other things. Further, Andriukaitis argues, blaming all excesses on a single state entity is probably unrealistic, since, he claims, no one blames the Wehrmacht for the Holocaust, whereas the SS and Gestapo were recognized as criminal organizations.

The Life Interview section of the book is followed by what appear at first glance to be short testimonials by others. Except very few of them are of the sort one might use in a political campaign. Instead, friends and political enemies were canvassed, and even some of Andriukaitis’s friends say some not entirely positive things about him. One of his former teachers, for example, remembers him as a radical. Another, a childhood friend, recalls a request to translate a tractate calling for armed resistance into Russian, something which I recall Andriukaitis presenting a little differently earlier in the book (although, truthfully, the biography is sufficiently long that I might be mis-remembering the episode at this point). What does come through from friend and “enemy” alike, and which runs through the entire biography as an undercurrent, is that Andriukaitis is a deeply principled man who has consistently refused to let politics overshadow his own humanity and friendships. This quality is perhaps his very best and overrides my personal qualms over his extremely statist, pro-state positions, although they are, most likely, fully in line with mainstream thinking on the mainstream parliamentary left in Europe.

◊

There are some problems with the book. The major one to me was Andriukaitis’s lack of evincing any critical thinking at all concerning his personal social democratic heroes, presented more or less in a hagiographic light in the book, including Willy Brandt, Gro Harlem Brundtland and assassinated Swedish PM Olof Palme. While Andriukaitis’s knowledge of Lithuania and Russia and politics in his region is impeccable, he doesn’t seem to have any ideas about the darker side of Swedish socialism, for instance, no personal experience of actually living under such a system, of cradle-to-grave “reeducation.” This carries over into what he says about Barak Obama, in essence, that he favors Obama’s “reset” with Russia over Bush’s war mongering. Elsewhere he takes to task Bush’s war in Iraq, asking rhetorically about the current state of Iraqi democracy, something Vladimir Putin joked about years ago in an attempt to be disarming, so to speak, during a meeting with the Americans. He also touches upon the Occupy movement (which must have been a current event when the actual interview was taking place) and quotes an American figure saying “Capitalism is dead.” The problem here, with what Andriukaitis says about American politics, is that he evinces a serious blind spot concerning what is really going on in America: Obama has continued and extended Bush’s authoritarian and military adventure policies, “capitalism is dead” has been given lip-service as cover for the corporate, not socialist, take-over of the American government and Obama hasn’t actually offered Russia any concessions beyond some mythical “reset button.”

On the other hand, Andriukaitis does know the whole story, and tells it, about Russian oil and gas lines going to Germany. He notes Lithuania rejected a Russian proposal to extend a pipeline through Latvia and Lithuania to cross Poland and terminate in Germany in the 1990s, whereas in the 2000s Lithuania made a loud fool of herself complaining to the EU that Russia had bypassed the Baltics by planning an underwater pipeline to Germany along the Baltic Sea bed, and that a land-line would have been more practical.

Another episode in the book caused me some incredulity as well, the parts dealing with the impeachment of Lithuanian president Rolandas Paksas in 2003. Andriukaitis presents the reasons behind the scandal as Paksas’s relation with a Yuri Borisov, alleged to have shipped helicopter parts to Somalia during some sort of embargo, and Paksas’s granting him citizenship and making him an advisor in return for campaign contributions. This was, of course, the cover story, but the actual story had more to do with the ambitions of other Lithuanian politicians and diktats emanating from the US State Department, revealed by then-foreign minister Valionis. Andriukaitis goes over Paksas’s political career and makes some correct points, but also some disingenuous ones. When Paksas was prime minister, for example, he refused to sign an agreement with the US company Williams, a decision with which Andriukaitis fully agrees. What Andriukaitis doesn’t like, however, is how Paksas resigned his post, allowing the acting PM to sign that exact same agreement. One gets the feeling there is some personal dislike at work in Andriukaitis’s version of events, for earlier in the same book he recounts the disappearance of acting-prime minister Simenis during the violent attacks by pro-USSR factions in Vilnius in January of 1991, and puts down to “naivete” Simenis’s decision to ride out the storm in hiding and thus at least preserve Lithuanian statehood in his own person as far as possible. Andriukaitis also makes a fuss, again earlier in the book, about how an ethical politician will resign during a scandal in order to come back later vindicated, something Andriukaitis has practiced himself, and successfully so. In hindsight it’s rather easy to say how prime minister Paksas should have acted in 2000, but in reality he was being presented with the specter of a constitutional crisis if he stayed on in the post at that point, presented such a specter by his, admittedly, politically more astute fellow conservatives.

Why does Andriukaitis stick to the cover story regarding the impeachment of Paksas as president? For one thing, he doesn’t like “conspiracy theories,” he tells us earlier on, a personal distaste he acquired during the ultra-paranoid and stressful days of the Lithuanian move to independence and the resulting Soviet economic blockade, and the “radicals” who seized power and would have seized more if they had been allowed and no one had confronted them.

◊

Fear and paranoia and conspiracies clump in Andriukaitis’s mind as a general state of mind to be avoided, undoubtedly a good coping mechanism for someone who himself came under the scrutiny of the Soviet security services numerous times. Even if Andriukaitis knows and in fact details in the book actual conspiracies matter-of-factly. Elsewhere he tells us he is something of a positivist by persuasion, and I suspect he means that in several senses, both as a philosophy of rational positivism, and as a general positive life philosophy. His positivism and enthusiasm imbue the entire biography, and I have met him in real life and can say he is very enthusiastic, and is a genuinely nice person who tends to have a twinkle in his eye and a real interest in those around him, despite wearing what might be a politician’s perma-smile. I almost get the sense his origins in the Arctic wastes, where the sun shines for months at a time without setting, has something to do with his overflowing energy, but I doubt he would agree.

Andriukaitis frequently quotes from the Bible, but seems to get his quotes slightly wrong. Of course, Jesus does the same thing in the New Testament, misquoting scripture and apocrypha, so perhaps this is completely acceptable. One assumes he does better when he quotes from the Russian classics. When the interviewer asks a question involving the word “cosmpolitan,” Andriukaitis goes back to Diogenes for a definition, skipping over the rather blatant origin of this word, currently being popularized again in Lithuania by the far right and neo-Nazis, in Nazi propaganda from the 1930s and 40s, “rootless cosmopolitanism” serving as a code-word for Jews, among other declared enemies of the Reich. There are surprisingly few typographical errors—missing letters in words, repeated lines of text—in a text running to some 550 pages.

◊

This is a genuinely important book for anyone interested in the modern history of Lithuania, and it is a great shame it has been largely ignored in Lithuania itself. While it would be difficult to translate the extremely high style and highly literary Lithuanian used into English, the result would undoubtedly outweigh the effort and serve the interests of fellow social democrats, political science researchers and future historians, if only for the light shed on the darker corners of the period of Lithuanian national rebirth, although the entire book is an important testimony to the highest qualities of man, the transcendence to freedom and the victory of rationality and reason over base instinct.

If you get the chance, read it.

A condensed translation into English would do Lithuania’s image the world of good, and in one fell swoop end the informational dictatorship of the hard (ultra)nationalist right that continues to do Lithuania a lot of harm.