OPINION | HISTORY | COLLABORATORS GLORIFIED | CHRISTIAN-JEWISH RELATIONS | LITVAK AFFAIRS

◊

by Andrius Kulikauskas

◊

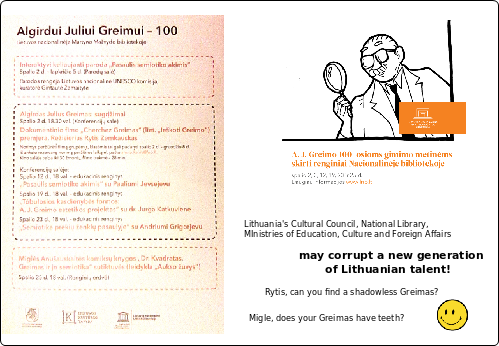

Renowned Lithuanian-French thinker Algirdas Julius Greimas (1917-1992) was more forthcoming than most about his dubious, or frankly, criminal behavior as a young man.

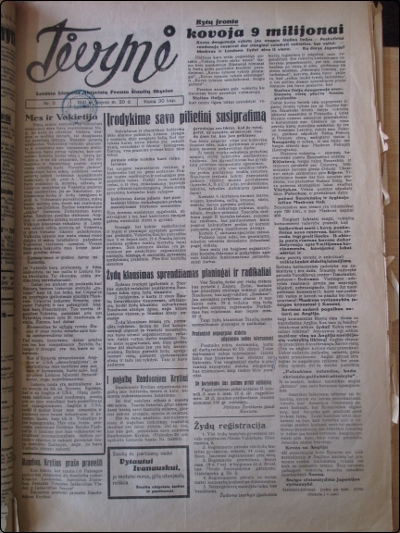

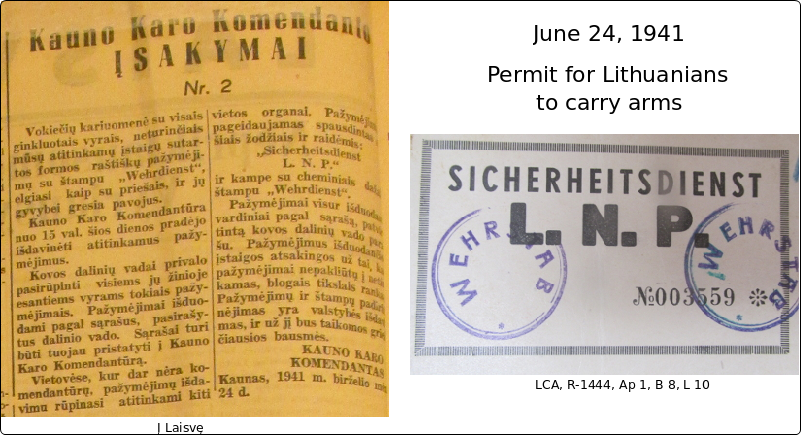

From his interviews we know that in 1940, he gave public speeches in support of Soviet annexation of Lithuania. And in 1941, he served as an editor for the newspaper Tėvynė in Šiauliai, which repeatedly called for ethnic cleansing of Jews from Lithuania.

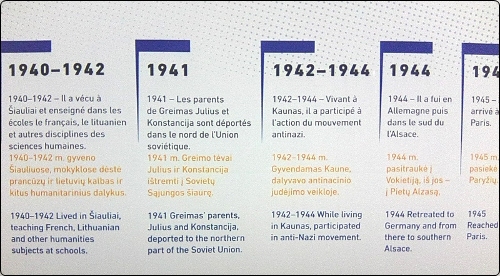

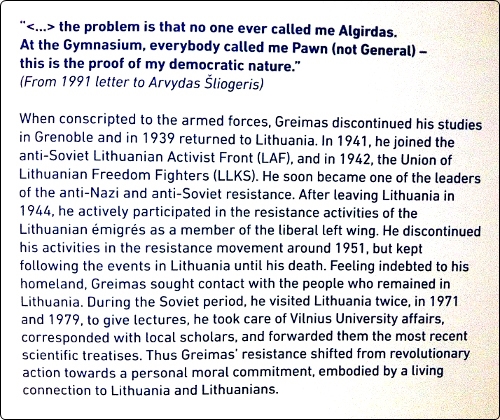

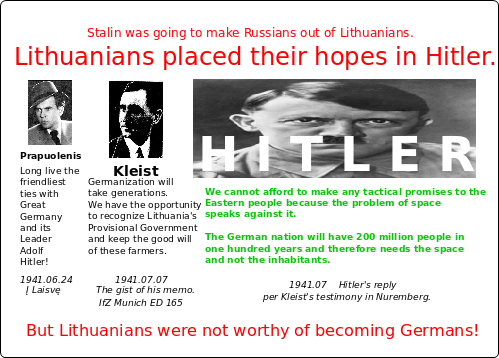

Unfortunately, Greimas’s crimes and victims have yet to be acknowledged in the international celebration of the centennial of his birth. A spacious exhibit at the Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania proclaims: “In 1941, he joined the anti-Soviet Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF), and in 1942, the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters (LLKS). He soon became one of the leaders of the anti-Nazi and anti-Soviet resistance.” This is the image of the intellectual patriot which Greimas scholars are crafting, UNESCO is sponsoring, artists are illustrating and the Lithuanian government is presenting to school teachers and children. But it is a half-truth which disrespects Greimas’s victims, his own self-admissions and his comprehensive way of thinking. In terms of the four corners of his semiotic square, the full truth is that he was pro-Soviet and pro-Nazi before he became anti-Soviet and anti-Nazi.

On January 30, 1992, a month before he died, Greimas emphasized in a letter to historian Saulius Sužiedėlis, that contrary to Lithuanian patriotic history, in 1941 there was no “rebellion” at all.

Greimas was responding to a sensational interview which historian Saulius Sužiedėlis had given in 1991 to the open-minded Lithuanian emigre newspaper Akiračiai (Horizons). Sužiedėlis revealed antisemitic excerpts from Kazys Škirpa’s original documents which he had discovered at the Turauskas archive in the Hoover Institute. In 1973, Kazys Škirpa had published a whitewashed account of how he had organized from Berlin the Lithuanian Activist Front and the 1941 anti-Soviet rebellion. We now know that after the war, Škirpa removed all references to the ethnic cleansing which was central to his strategy of mobilizing Lithuanians to “volunteer” by inciting them to blame, hate, attack, rob and drive out all of their Jewish neighbors.

The Lithuanian government has no plans to publish the originals but they are easy to find in Lithuania’s Central Archives (search on “Škirp” to include various Lithuanian morphological endings) and Defending History has made them available online. In fact, the National Library itself has an archive of Škirpa’s documents, yet to be organized, which includes a copy of the LAF program in which he has crossed out the criminally antisemitic 16th article and renumbered the subsequent articles. At the time of his interview, however, Sužiedėlis was terribly slandered as a dupe of the KGB and a traitor. Greimas set down for Sužiedėlis his own personal perspective, which Akiračiai published, and we translate and share.

◊

Regarding the Year 1941 in Lithuania

“As a direct witness, I wish to document several events from the summer of 1941 in Šiauliai, where I was at the time a teacher at a high school for adults. My reason is that the Lithuanian Front Activists have unnecessarily idolized these “battles for independence”. P. Tysliavienė, having brought her husband’s ashes to Vilnius [in 1962], visited me in Paris upon her return. She brought documents which the [Communist] Party had given her about the “liberators'” cruelties in Šiauliai county, which don’t accord with the truth. I think that a few facts can help you form a sober, more or less objective view of the events and atmosphere of those days.

“1. I was recruited into the LAF in March by one close acquaintance, a former Scout leader. I heard nothing more about this underground until the German army occupied Šiauliai (it seems the fourth day after war was declared). Which is to say, there was no “rebellion” at all.

“2. The next morning, having heard that the “partisans” were gathering at the former seminary for teachers of girls, I hurried over there. Numerous people were gathering. As an officer in the Army reserve, at once I became a platoon leader, and I took up various activity (for example, using the seminary’s seal to give a permit to the former bakery director to open his bakery so that the city would have bread, and so on.) In the afternoon, so many men had gathered that they now assigned me to lead a company (about 200 people). The people, of course, were unarmed.

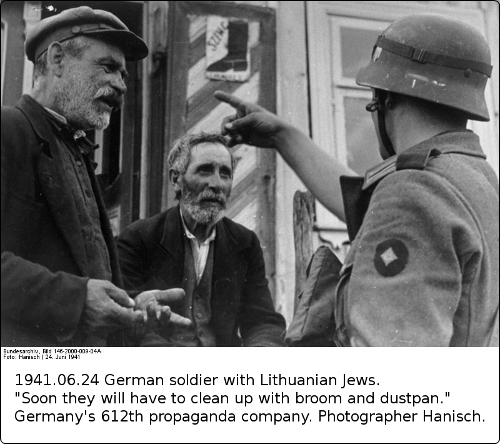

“Unexpectedly there came an order from the German commandant: to round up and present 100 Jews (or more?) to sweep the streets. An astonishment, some kind of uncomfortable feeling, that something’s not right: I handed down the order and the next morning I did not show up to “liberate” any more. And so, the first, comparatively insignificant order regarding the Jews came from the German commandant.

“3. A couple of weeks having gone by — I had then taken over the editing of the Šiauliai weekly — I was invited to the staff meeting of the Lithuanian Activist Front.”

◊

At this point in the narrative, a Greimas scholar might be excited to discover what the young man may have written in that weekly, Tėvynė (Parentland), which can be downloaded here (125 MB), and found in the National Library’s stacks, although not in the centennial exhibit. A more sober reader will stop to realize that Greimas, despite his good intentions, has incriminated himself, perhaps unwittingly. We see that Greimas handed down an order to abuse 100 Jews. And yet this is “comparatively insignificant” compared to his work as an editor. The early issues of Tėvynė consistently urge the eradication of Jews from Lithuania. But let us return to Greimas’s recollection of that first LAF meeting…

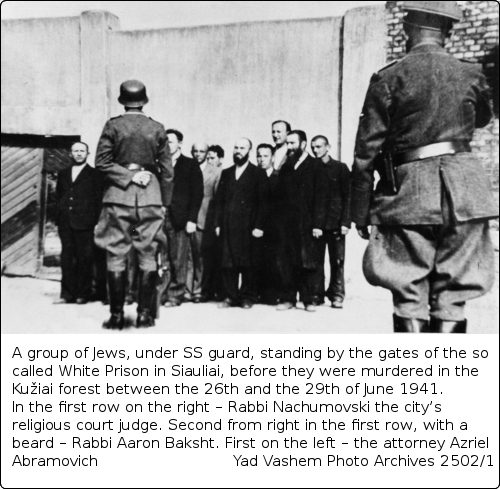

“The meeting heard a report about the previous night’s events. Two of the Front’s officials were summoned by the Germans to the Šiauliai prison. The German prison commander explained that Lithuanian “partisans” from neighboring towns had brought in so many groups of “Communists” that the prison had nowhere left to put them. In the prison yard he placed a small table, set down the lists of “Communists” and ordered X’s to be placed next to the surnames of those who were “real Communists”. And then and there they were shot. Thus:

“a) the first to be murdered were “Communists” and not Jews;

“b) the murders were conducted by Germans, and not Lithuanians ([and] not because [the victims] were guilty of anything, but for practical purposes).

“The Activist staff, at the suggestion of the former chief of secret police in Šiauliai, decided to establish a “Lithuanian prison,” and to receive there the flocks of “Communists” which were never brought, and upon receiving them, to set them free through the back door, so that they would hide somewhere until the turmoil passed. And so, the Front performed a humanitarian deed, restraining local initiatives, the settling of scores and so on.

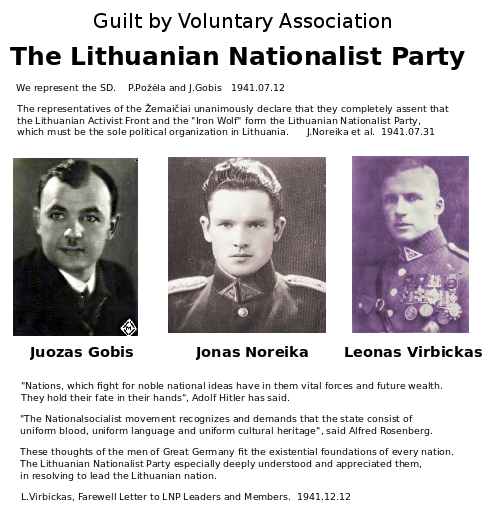

“4. While the staff was meeting, two unknown citizens barged in: attorney Požėla and teacher Gobis (a prominent Catholic activist, the author of pedagogical booklets). They introduced themselves saying that they represent the S.D. (Sicherheitsdienst), about which we heard for the first time, that compared to it the Commandant and the Gestapo were to be spit upon, that we had to listen to them, and that from now on we were to call ourselves the Nationalist Party. And they left.

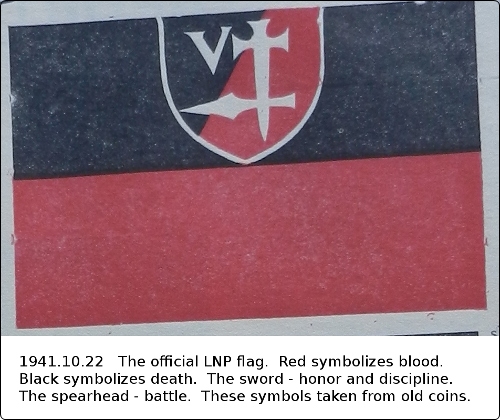

“Silence came over us. Major Vilutis (a moderate Voldemarist), chief of staff, advised us to think about it overnight, and in the morning, next to the “Lithuanian Activist Front,” he hung up a sign “Nationalist Party”. The staff continued to work peaceably, as much as it could work, and soon enough disbanded.

“Attorney Požėla soon became known as a murderer of Jews in the towns of Šiauliai county. Towards the Spring, in 1942, I think, he was shot by the SS itself.

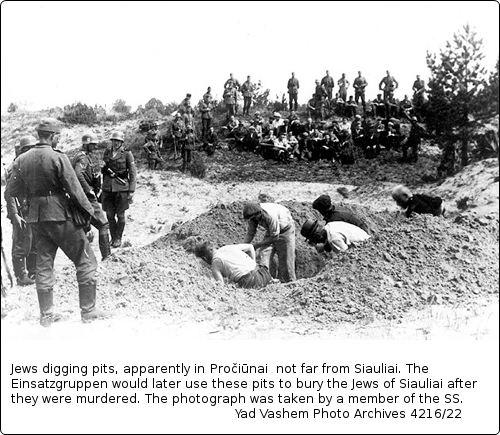

“And so the Wehrmacht was rather “soft” as regards the Jews, whereas the S.D. and the Einsatzgruppen under its direction actively conducted the liquidation of Jews.”

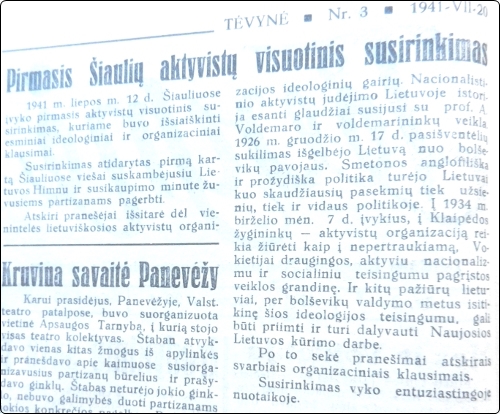

The July 20, 1941 issue of Tėvynė includes a report on this first meeting of the LAF staff in Šiauliai. The meeting “clarified fundamental ideological and organization questions.” “The history of the Nationalist Activist movement is closely related to the activity of Prof. A.Voldemaras and the Voldemarists.” “Smetona’s anglophilic and pro-Jewish politics had the most painful consequences for Lithuania, in foreign politics as well as internal politics.” “The meeting took place in an enthusiastic spirit.”

We can learn more about Greimas’s mindset from the forthcoming Volume I of Asmuo ir idėjos (Person and Ideas), an early copy of which was made available at the 13th World Congress of Semiotics in Kaunas on June 26-30, 2017. Greimas confessed in an interview with Kavolis:

“Today it is impossible to understand that deliria, that madness, which in the [fourth] decade of the 20th century had overcome the youth of all of Europe, that “devil of action” that had possessed it: to act, necessarily to act, to do something, to break at any cost… A youth became a Fascist or Communist simply because of their surroundings or circumstances.”

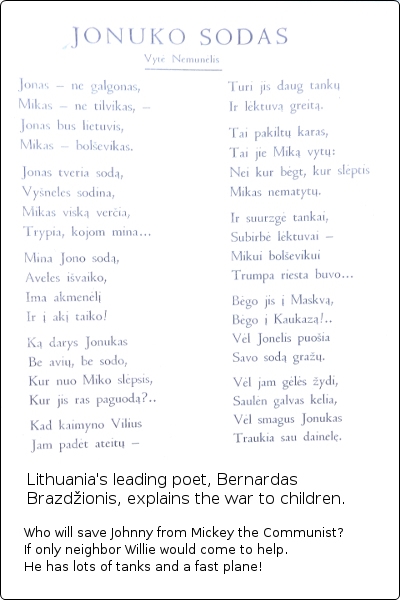

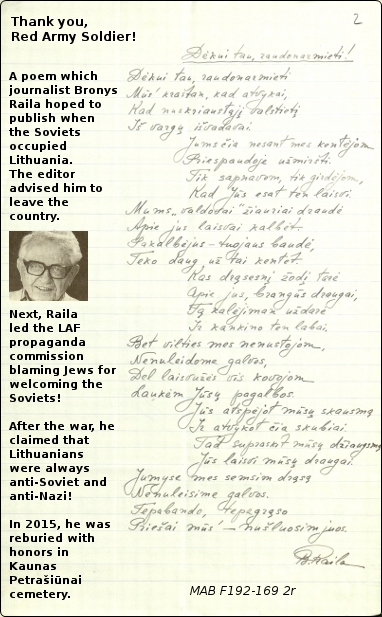

Also noteworthy about Greimas was the range of friends who influenced him. We read on page 659 that Greimas was assigned to urge his fellow Lithuanians to vote for annexation to the Soviet Union. He dutifully performed, as his lifelong buddy and alleged KGB lackey Aleksys Churginas taught him, “a few stylistic devices of the new regime: every speech should end mentioning comrade Stalin; immediately after the speech one should applaud oneself.” Another lifelong pal was Bronys Raila, the prolific author of nasty LAF propaganda, as well as poems glorifying the Soviet occupying army. Raila and Greimas were active in the Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters.

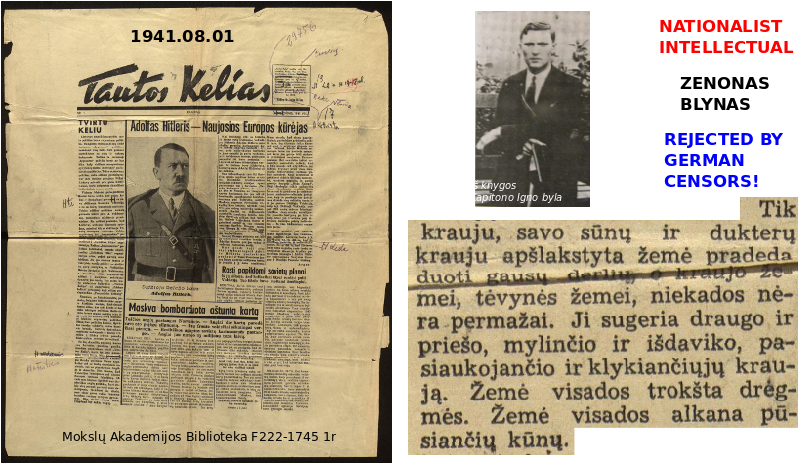

What was Greimas’s role in Tėvynė given that the editor is listed as Vladas Pauža? From Asmuo ir idėjos we also learn that Vladas Pauža was indeed the Scout leader who recruited Greimas into the LAF. And from Zenonas Blynas’s diary we know that Pauža was in Kaunas right after the Voldemarist / LNP coup of July 23-24, 1941, in which they failed to replace the Provisional Government but succeeded in deposing Bobelis, taking charge of the Lithuanian forces and commanding them in genocide. Indeed, Pauža was part of an LNP attempt to take over the Kaunas newspaper Į Laisvę (To Freedom) from LAF and replace it with Tautos Kelias (The Nation’s Path). Fortunately, the German censors refused a change in publishers. The mock up of the first issue of Tautos Kelias is the most vile of any Lithuanian propaganda ever, with the LNP intellectual Zenonas Blynas ranting that no child is too little for the blood-thirsty earth. All of this to conclude that with Pauža in Kaunas, we can credit Greimas as the editor of the July 27 issue.

◊

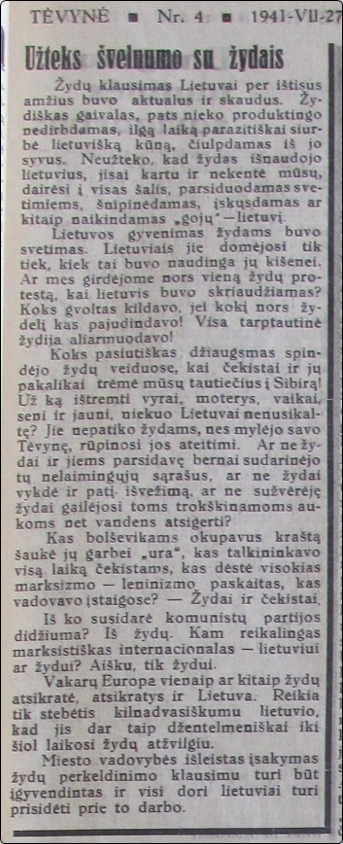

Enough with the Softness towards the Jews

“The Jewish question has been relevant and painful for Lithuania for entire centuries. The Jewish force of nature, itself doing nothing productive, for a long time parasitically sucked the Lithuanian body, drawing its sap. It was not enough that the Jew exploited Lithuanians, he also hated us as well, […]

“Western Europe one way or another has rid itself of Jews, and Lithuania will rid itself as well. We must only marvel at the noblespiritedness of the Lithuanian, that till now he still behaves so gentlemanly with respect to the Jews.

“The order issued by the city’s administration regarding the transfer of the Jews needs to be implemented and all decent Lithuanians must contribute to this work.”

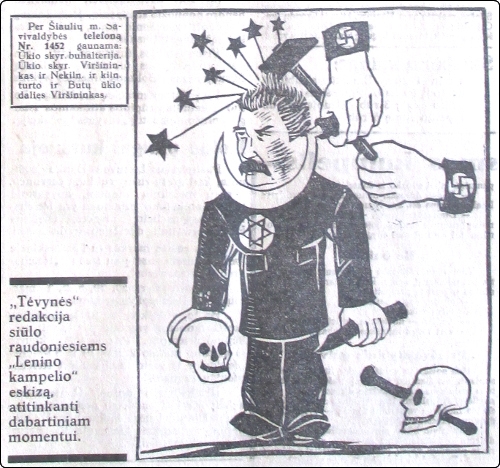

We don’t know who wrote this editorial, although Greimas’s concept of “softness” may serve as his signature. Ultimately, all we have is his own word that he was the editor. But all of the early issues are basically the same. Here is a cartoon from that same July 27 issue.

Greimas’s letter makes no mention of his own personal tragedy. On June 14, 1941, just days before the events he describes, the Soviets arrested, separated and deported his mother and father. It’s to be noted that there’s no sense of revenge in any of his thoughts. It’s also evidence that truly it is a myth, which Kazys Škirpa concocted and Bronys Raila promoted, that Lithuanians wronged Jews out of revenge.

We see from Greimas’s own letter and from Tėvynė that in Šiauliai the distinction between LAF and LNP was in his own mind but perhaps not in reality. The leader of the LNP for all of Žemaitija, also based in Šiauliai, was Jonas Noreika. After the coup, Noreika led a delegation to encourage the LAF leadership in Kaunas to merge with the LNP. Leonas Virbickas was the leader of the LNP for all of Lithuania. He gave a speech at the banquet which battalion leader Kazys Šimkus held on November 29, 1941 to congratulate Karl Jaeger on killing all of Lithuania’s Jews. “Before a great celebration, Lithuanians are used to cleaning house.”

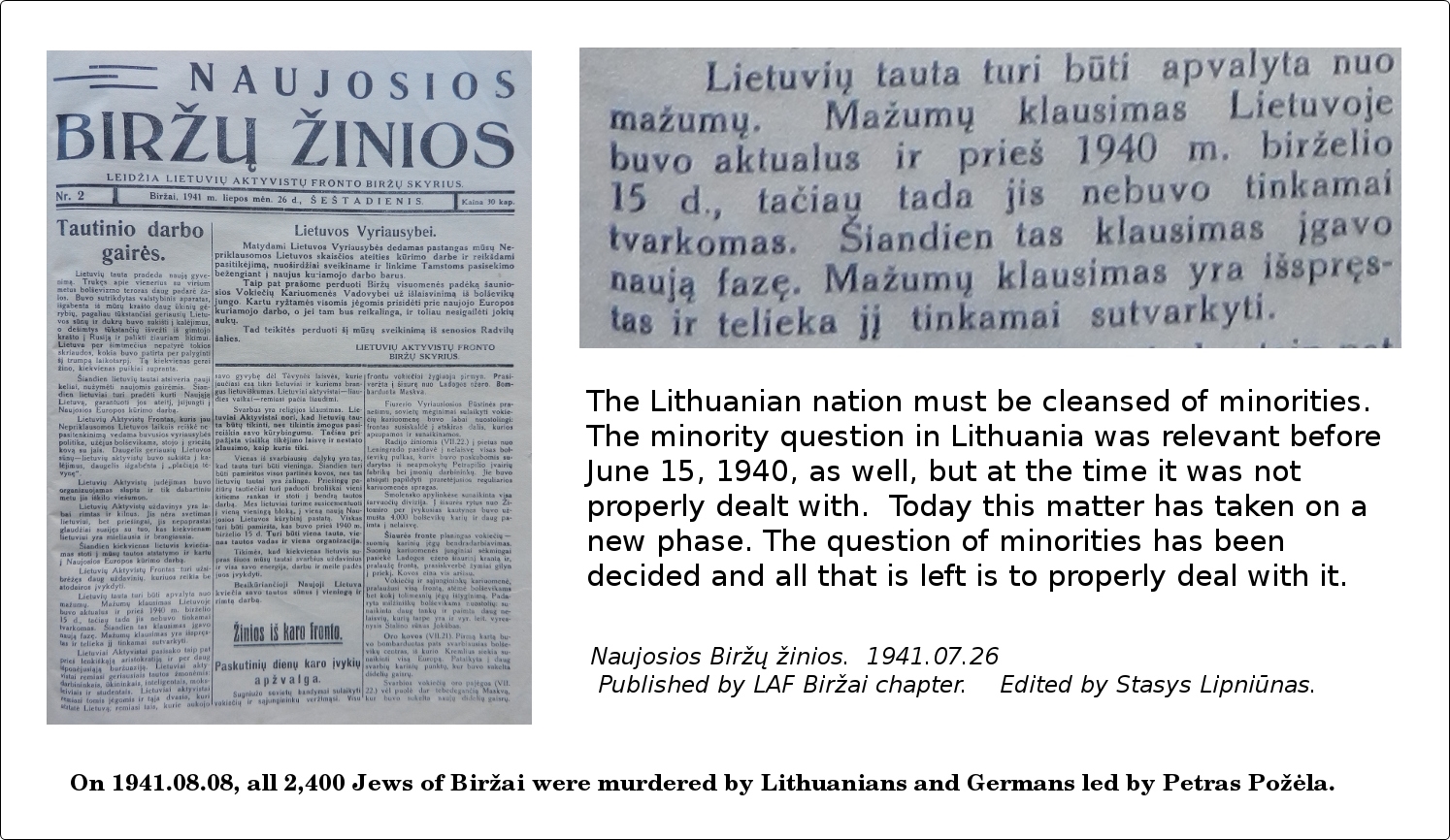

Greimas’s letter brings out the role of Petras Požėla and the SD. The Einsatzgruppen were the major German killing machine, and part of the SS. It seems that in Lithuania, the SD was mostly just one German — Martin Kurmies — working for Heinz Graefe, who was giving cover for the genocidal Lithuanian Nationalist Party, as an alternative to Lithuania’s Provisional Government. Clearly, by Greimas’s own logic, Tėvynė and other Lithuanian antisemitic newspapers must have had a murderous influence on local Lithuanians. This is especially evident in Biržai, where Naujosios Biržų žinios published a horrific front-page editorial on July 26, 1941, “Guidelines for National Work”, which concludes “The Lithuanian nation must be cleansed of minorities.” Two weeks later, on August 8, Požėla led 80 Lithuanians and a few Germans in the murder of all 2,400 Jews in Biržai. Future Lithuanian superstar, 18-year old Jonas Mekas, joined the newspaper that fall.

The pen is mightier than the sword. President Smetona entrusted his officers with swords, commanding them, “Do not raise it without cause. Do not lower it without honor.” Intellectuals, authors, editors and publishers should likewise be held to account for their actions.

- Philosopher Antanas Maceina wrote and Kazys Škirpa and Antanas Valiukėnas edited the Lithuanian Activist Front program, which “revoked hospitality” from the Jewish minority. This text ended up in Kaunas LAF leader Prapuolenis’s final speech, signed by Damušis and the other Kaunas LAF leaders.

- Lithuania’s leading diplomats Stasys Lozoraitis and Petras Klimas wrote letters to Škirpa approving his proclamations urging ethnic cleansing.

- Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis, Zenonas Ivinskis, Jonas Grinius and Jonas Virbickas published the first uncensored issue of Į laisvę with words that fueled antisemitism during the Vilijampolė pogrom.

- The Lithuanian Provisional Government’s Ministry of Agriculture’s Chamber of Agriculture published Ūkininko patarėjas (The Farmer’s Advisor), a newspaper with a circulation of 50,000. It called for ethnic cleansing of Jews from Lithuania.

- Philosopher Juozas Girnius wrote a four-part article, “The Conceptual Foundations of National Socialism”, for Į laisvę, which had a circulation of 200,000.

In 1941, as the Holocaust was taking place, Lithuania was morally bankrupt. The Jewish museum has scant evidence of any Lithuanians standing up for Jews in that year when it mattered most. The reason is evidently that it would raise too many questions. Dovid Katz has taped numerous interviews in Yiddish with Jewish survivors eternally grateful to Lithuanians who saved them from other Lithuanians during the first days of the war. Vytautas Landsbergis-Žemkalnis’s family saved Jews, but his vice minister was in charge of the Lithuanian Provisional Government’s concentration camp, presumably at Kaunas VII fort, where thousands of women and children went for days without food or water. Jurgelis Bobelis’s family hid Jews, but he handed down the order by which the Voldemarists led the machine gunning of about 3,000 Jews and Communists at Kaunas VII fort on July 4-6, 1941.

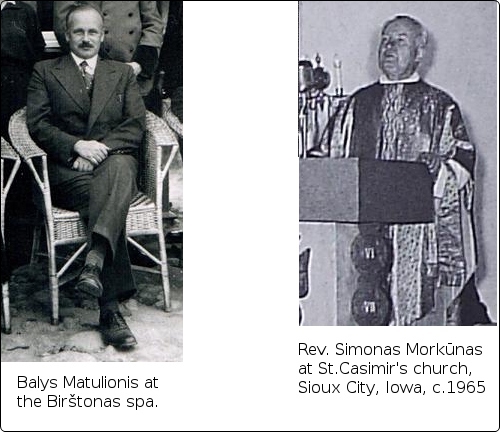

On the day of the Lietūkis massacre, physician Balys Matulionis and priest Simonas Morkūnas went to Archbishop Juozapas Skvireckas to urge the Roman Catholic Church to take action. But these two righteous men have yet to be held up as examples. The problem is that we know of them from the Archbishop’s diary, where we can also read that Hitler had some good ideas, that Jews should understand their place is in the ghetto, and that Bishop Vincentas Brizgys told the Jews that he and other priests could not stand up for them because then their fellow Lithuanians would lynch them as well.

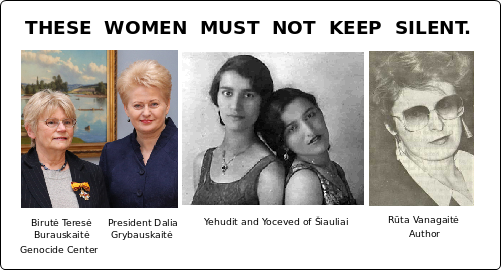

Around the world, we need people like President Dalia Grybauskaitė, who stands up to Russian President Vladimir Putin. We don’t need 2-dimensional heroes, but rather 3-dimensional citizens and 4-dimensional thinkers. As Greimas concluded in his essay “About Beautiful Gestures”:

“You know the advice which the wisdom of elders gives to beautiful women, ‘Be beautiful and keep quiet!’ It’s the same with heroes, ‘If you want to be a hero, don’t think!'”

In Lithuania, the Genocide Center is thinking. It has taken the first welcome step in condemning the Lithuanian Nationalist Party, thanks to a query by Lithuanian citizen Grant Gochin. On October 24, 2017, it responded:

“All the same the surviving LNP program documents, press, and public statements clearly testify to this party’s antisemitic ideology. Some of the LNP leaders (for example, major K. Šimkus) and a part of the ordinary members, especially those who served in the Lithuanian police battalions, are responsible for crimes made during the Holocaust. One of the Center’s directions of activity is the investigation of the Nazi-occupation and crimes made at that time. We think that in the future it would be appropriate to investigate the LNP as well and to confirm this question as a distinct topic of investigation.”

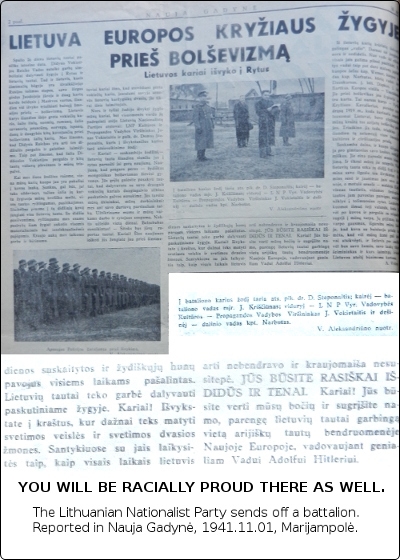

The Lithuanian Encyclopedia article published in Boston, 1958, credits the Lithuanian Nationalist Party with organizing five battalions. Whereas the recent monograph by Arūnas Bubnys, Lietuvių policijos batalionai 1941-1945 details the battalions’ genocidal activity, but makes no mention of the LNP, whose letters the first battalion’s members were ordered to wear on their armbands. For the sake of genocide, the LNP organized a coup to depose Bobelis, took over the battalions, established the Kaunas Ghetto, vetted the battalion leaders and publicly sent the battalions off to other countries “to be racially proud there as well.”

The political “problem” today is that, for a while, the Lithuanian Nationalist Party, whose principal achievement was organizing genocide, was the only legal Lithuanian organization in which ambitious Lithuanians such as Jonas Noreika might be active. After Lithuania’s Jews were killed, the Nazis shut down the party, and many of its leaders became the basis for the underground Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters. In the second part of his letter, Greimas writes:

“The Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters (to which I, too, belonged) was a strange mixture of Liaudininkai (Žakevičius, Deksnys), Tautininkai (Drunga-Valiulis) and Voldemarists (Brunius), which had regular radio links through Sweden (Vokietaitis) with the English Intelligence Service.”

Brunius was a co-leader of the LNP, Deksnys was part of the coup, and Algirdas Vokietaitis and Drunga-Valiulis were active as well. Stasys Žymantas-Žakevičius was the leader of the Vilnius committee which advocated ethnic cleansing of Jews but also Poles as well.

The Union of Lithuanian Freedom Fighters, or rather, its continuation, has never had to condemn the Lithuanian Nationalist Party. Politically, this is a complication, when the Union is heralded by the National Library exhibit or by Lithuania’s Ministry of Defense without anyone having to reflect on the crimes of its organizers. Understandably, Lithuanian patriots wish to wipe away decades of Soviet slander.

Unfortunately, many of the accusations are true, and we need to think of the victims, and to look from all sides. Certainly, we must not romanticize guerilla war, but know it and state it for the tragedy it is. Justinas Sajauskas, in his book Neužmirštami Suvalkijos vardai (Unforgettable Names of Suvalkija), details hundreds of cases which show how guerilla war degenerates. Partisans end up killing teenage Communist snitches and the very farmers who have grown tired of feeding them. Here is Greimas’s reply to a question by Kavolis in 1985:

“I used to look at politics as a serious matter, especially when our nation fell into maelstroms of violence and rupture. Having looked over those years ‘gone wasted,’ I can at least console myself to have participated in and at least somewhat contributed to three significant actions: the strict pronouncement by the underground Freedom Fighter newspaper against forming a Lithuanian SS Legion and against any other recruitment of the youth on behalf of the Germans; the encouragement to progressively liquidate the pointless anti-Soviet resistance in the forests; and the invitation of the diaspora to engage the nation ‘facing towards Lithuania’.”

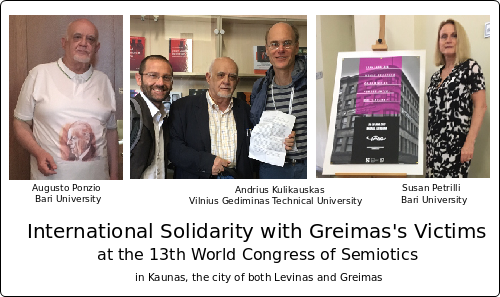

Ignoring the truth just makes matters worse. Some 500 scientists came to Kaunas for the 13th World Congress of Semiotics, and a dozen were disappointed to learn that the Vilnius University’s Greimas Centre of Semiotics and Literary Theory had declined a request for a moment of silence to honor Greimas’s victims. Among those who appreciated the request were fans from Italy of Lithuanian Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. This gave a glimpse of how unpleasant it would be to have a convention center in Vilnius on top of a Jewish cemetery.

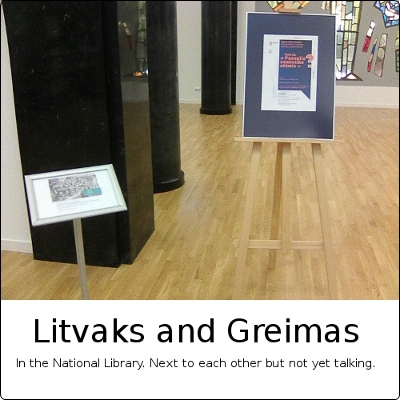

This year, the Mažvydas National Library opened the Damušis Center and displayed an exhibit of Klimas’s family photos with no recognition that both of these men publicly advocated ethnic cleaning. In the case of the Greimas exhibit, it was curious to see it side-by-side with an exhibit on Jewish cultural and civic life in independent Lithuania, 1918-1940.

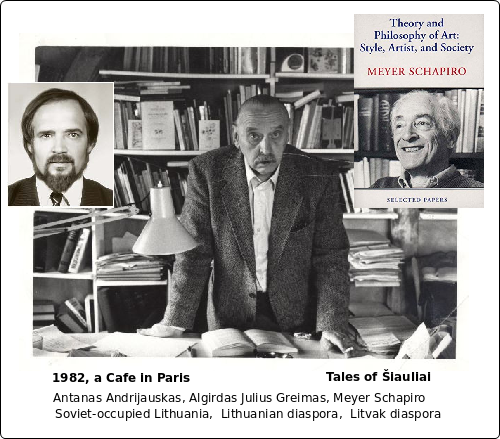

We round out our picture of Algirdas Julius Greimas by celebrating his lunch in Paris with Meyer Schapiro and Antanas Andrijauskas in 1982. Meyer Schapiro was an innovative, interdisciplinary Jewish-Lithuanian-American art historian. He was born in Šiauliai, the city of Greimas’s victims, in 1904, and came to New York at the age of three. When they met, Greimas was 65, Schapiro was 78, and Andrijauskas was a 34-year old scholar from Soviet-occupied Lithuanian. We thank Vilnius Gediminas Technical University (VGTU) philosopher Tautvydas Vėželis for alerting us to this historic meeting. Andrijauskas recalls:

“Now I have received two letters on the very painful subject for us, the Litvaks. This grieves me, for I feel guilt and pain for their tragedy. I am amazed at our people’s refusal to admit obvious truths.

“That took place long ago, 35 years ago, when in 1982 Schapiro had come to Paris to the reception for the translation into French of his enormous book, Style, Artiste et Société (1982), which had just been put out by the famous Gallimard publishing house. To this day I have this book in my personal library.

“They had already arranged to meet, and when Greimas learned that I know of Schapiro, and furthermore, before the war my father lived for a time in Šiauliai — he invited me to join them.

“The meeting was in a little cafe on the right bank of the river. We spoke about the conditions for science in the US and France, about Lithuania, Šiauliai, the politics of the USSR and the enslavement of Lithuania, and the necessity of helping the people of Lithuania. (2017.08.14)

“Schapiro in that conversation was very interested in Litvak cultural heritage, especially the problem at that time in Lithuania of preserving the artifacts which the synagogues had collected, but that was a completely forbidden topic in the Soviet Union at that time. (2017.08.15)”

◊