LITHUANIA | HISTORY | KAUNAS | MUSEUMS

◊

by Michael Samaras

◊

◊

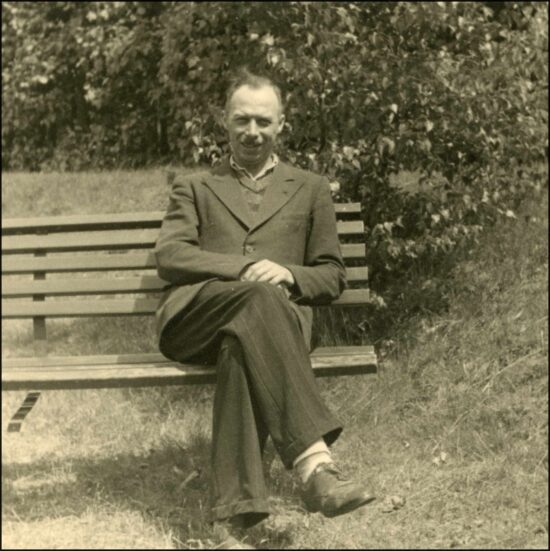

Wollongong, an Australian city located about 80 kilometres south of Sydney, is a long way from Lithuania’s Kaunas, which probably made it attractive to Bronius Sredersas. He arrived in 1950, having fled Lithuania ahead of the Red Army in 1944. For the next 25 years Sredersas, one of more than 100,000 displaced persons to settle in Australia, worked in Wollongong’s steelworks. He led an unobtrusive life and acquired an anglicised nickname, “Bob”. He never married and didn’t waste his money. Instead, he saved his pay, frequented auction houses and with a canny eye built a substantial art collection.

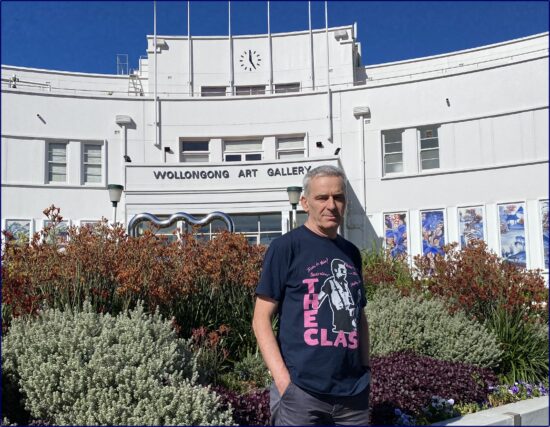

In 1976, Sredersas shocked the citizens of his adopted city by presenting his art collection to them. For an industrial city like Wollongong, which didn’t even have an art gallery, this gift was a sensation. It triggered the establishment of the Wollongong Art Gallery which has since grown into a major regional cultural institution.

Sredersas was widely celebrated in the media and an exhibition space within the new gallery was named in his honor. After his death in 1982, his memory was preserved with eminent persons giving lectures in his memory. The gallery erected a plaque and hosted the Sredersas Dinner as a fundraising social event.

In 2018, the gallery staged a major exhibition celebrating Sredersas. Titled “The Gift”, the exhibition included a recreation of his home, a display of the artworks, a video, and a symposium on his life and benefaction.

Publicity for the exhibition included mention that in Lithuania, Sredersas had been a policeman. While I was aware of Sredersas’ life as a steelworker in Australia, his prior career as a policeman was new to me. I knew though that the Nazis had relied on local collaborators, formed into police battalions, to carry out the Holocaust in Lithuania. I was appalled at the possibility that Wollongong, my home town, might be honoring a Holocaust perpetrator and decided to see if I could find out more.

A search of the National Archives of Australia yielded the International Refugee Organization papers about his arrival in Australia. As well as routine particulars such as his date and place of birth, religion, marital status and education, the documents confirmed he had worked as a policeman in Kaunas and Vilnius.

I visited the Wollongong City Library and reviewed the Sredersas files which contained a birth certificate showing he was christened Bronislav Schreders. There were photographs and sundry documents which established that in Wollongong he did not talk about his experiences in the Second World War.

I was determined to learn more and the pandemic lockdowns provided me with time to think about Nazi war criminals. I read Gitta Sereny’s Into That Darkness: From Mercy Killing to Mass Murder, which recounts her time with Fran Stangl, the former Kommandant of Treblinka, and Gerald Steinacher’s Nazis on the Run: How Hitler’s Henchmen Fled Justice. I read fictional works including Martin Amis’ Time’s Arrow and Bernhard Schlink’s The Reader, watched The Boys from Brazil and Marathon Man, and television shows such as the ludicrous, but still entertaining, Hunting Hitler.

Eventually I found another IRO document where Sredersas provided another version of his career:

From 1935 to 1940 I worked as a policeman. From 1942 to 1944 I worked on a ship as a seaman. From 1946 to 1947 I attended the Navigation and Sea-Engineering School. From 4th October 1948 to 4th December 1948 I worked as a seaman.

The absence of any account of what he did in the year 1941 was glaring. This was when most of the Jews of Lithuania were murdered, but the IRO had not asked Sredersas what he did during those extraordinary months and he had offered no account.

A Holocaust survivor from Kovno, Joe Melamed, had published lists of perpetrators, but he’d died in 2017 and I could not find his research. Eventually, I found a web journal called Defending History and emailed the journal’s editor, Dovid Katz, to see if he had Melamed’s lists, but he couldn’t send them to me at that time because of travels. The exercise was not futile though, because Katz forwarded my email to Evaldas Balčiūnas, who suggested the Lithuanian archives would undertake searches for me and I immediately lodged applications. [Note: Melamed’s 1999 book Crime and Punishment is now on line in two PDFs, here and here.]

On 24 December 2021, I received a document from the Lithuanian Central State Archives and used Google Translate to establish that it was an application made by Bronislaus Schroeders to join the Waffen SS. The documents contained the standard biographical information and named his current employer as the “S.D.”

My first task was to confirm Schroeders was the same person known as Sredersas which I did by comparing the details in the different documents. This exercise showed the date of birth, place of birth, religion, marital status and parents were the same. There was no doubt Schreders, Schroeders and Sredersas were one and the same.

I turned to his employment with the SD (Sicherheitsdienst), the intelligence arm of the SS. The SD was central to the implementation of the Hitler’s program to murder millions of Jews and others across Europe. The activities of the SD had been considered by the Allies’ International Military Tribunal at Nuremburg, with the SD being declared a criminal organization.

I knew confirmation by an expert was required and sent the documents to Dr Efraim Zuroff, the Coordinator of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre’s Nazi war crimes research effort. He replied:

The fact that in 1943, he worked as a criminal investigator for the German Sicherheitsdienst in Kaunas (Kovno), means that he was involved in implementing German policy regarding the Jews, i.e. the Holocaust.

On 13 January 2022 I contacted the Wollongong Art Gallery and emailed the documents and Zuroff’s evaluation. On 20 January 2022 I received the Council’s response:

Thank you for the information. I understand you are deeply concerned about the Gallery’s reputation. On balance, given the lack of clear evidence in this case, it is not deemed appropriate for Council — as a local government body — to undertake such an investigative role as suggested. As such, Council does not propose to take any further steps in this matter at this time.

It was astonishing that Wollongong Council was apparently not concerned its gallery was honoring a person who had been involved in the Holocaust. Consequently, I took the information to the media and contacted Paul Daley, a writer at the Guardian. His article, “‘I am Bob. Just Bob’: could a Wollongong folk hero have had a Nazi past?” appeared on 21 March 2022.

Within days the Council agreed to engage Professor Konrad Kwiet of the Sydney Jewish Museum to review the case.

In June 2022, Professor Kwiet’s report affirmed that Sredersas’ “war time position within the SS and Police apparatus made him complicit to the Holocaust and other hideous crimes perpetrated.”

The Council responded promptly to Professor Kwiet’s report, stating that Wollongong’s relationship with Sredersas would change. As a first step, the plaque honoring Sredersas was removed, as was the name plate from the exhibition space previously known as the Sredersas Gallery.

Post-war Australia was a place where tens of thousands of survivors came to try to build new lives. It was also a place where perpetrators came to escape responsibility for their criminal actions. It is not clear why, after evading detection for so long, Sredersas willingly chose to make himself a figure of renown through his cultural benefaction. The truth about his motivations will likely never be known.

What is certain is Sredersas worked for the murderous SD, lied his way through post-war screening, and made a new life for himself. After years of living unremarkably, he made an important cultural gift and was well-honored for it. A historical investigation established at least some of what he concealed, and Wollongong will now no longer honor one of “Hitler’s Willing Executioners.”