LITHUANIA | HISTORY | KAUNAS | MUSEUMS

◊

by Michael Samaras

◊

◊

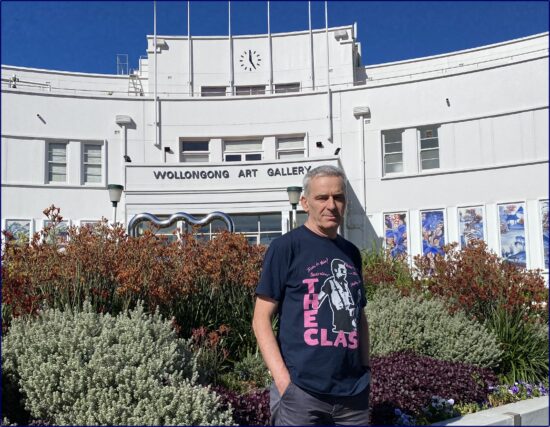

Wollongong, an Australian city located about 80 kilometres south of Sydney, is a long way from Lithuania’s Kaunas, which probably made it attractive to Bronius Sredersas. He arrived in 1950, having fled Lithuania ahead of the Red Army in 1944. For the next 25 years Sredersas, one of more than 100,000 displaced persons to settle in Australia, worked in Wollongong’s steelworks. He led an unobtrusive life and acquired an anglicised nickname, “Bob”. He never married and didn’t waste his money. Instead, he saved his pay, frequented auction houses and with a canny eye built a substantial art collection.

In 1976, Sredersas shocked the citizens of his adopted city by presenting his art collection to them. For an industrial city like Wollongong, which didn’t even have an art gallery, this gift was a sensation. It triggered the establishment of the Wollongong Art Gallery which has since grown into a major regional cultural institution.

Sredersas was widely celebrated in the media and an exhibition space within the new gallery was named in his honor. After his death in 1982, his memory was preserved with eminent persons giving lectures in his memory. The gallery erected a plaque and hosted the Sredersas Dinner as a fundraising social event.

In 2018, the gallery staged a major exhibition celebrating Sredersas. Titled “The Gift”, the exhibition included a recreation of his home, a display of the artworks, a video, and a symposium on his life and benefaction.

Publicity for the exhibition included mention that in Lithuania, Sredersas had been a policeman. While I was aware of Sredersas’ life as a steelworker in Australia, his prior career as a policeman was new to me. I knew though that the Nazis had relied on local collaborators, formed into police battalions, to carry out the Holocaust in Lithuania. I was appalled at the possibility that Wollongong, my home town, might be honoring a Holocaust perpetrator and decided to see if I could find out more.

There is, however, disturbingly, quite a stupendous missing link in this abridged history of Lithuania in the twentieth century. Where had the quarter million Jews (the figure on the eve of the Holocaust) of the country disappeared to “overnight” (as centuries go), during that fateful century? Had there ever been a Jewish minority in Lithuania at all? When I looked at the author’s pedigree, I understood why the Jews had not played any role of significance in his biased dialectical discourse. Joren Vermeersch is a historian (of sorts) and an accomplished author. He is also a representative (stand-in, as we call it) for the Belgian House of Representatives, for the “N-VA.” This is the nationalist Flemish party that has its historical roots in the collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. The party that has systematically fought for an amnesty for Nazi collaborators. The party in which the grandparents or parents of some of the present actual leaders had been condemned by the Belgian State for collaboration with the enemy. Nobody is guilty of sins of their ancestors, but when there is a pattern of such pedigree being considered a great plus for current leadership, and that pedigree is subtly glorified rather than disowned, we have a current moral problem that merits discussion in the public square.

There is, however, disturbingly, quite a stupendous missing link in this abridged history of Lithuania in the twentieth century. Where had the quarter million Jews (the figure on the eve of the Holocaust) of the country disappeared to “overnight” (as centuries go), during that fateful century? Had there ever been a Jewish minority in Lithuania at all? When I looked at the author’s pedigree, I understood why the Jews had not played any role of significance in his biased dialectical discourse. Joren Vermeersch is a historian (of sorts) and an accomplished author. He is also a representative (stand-in, as we call it) for the Belgian House of Representatives, for the “N-VA.” This is the nationalist Flemish party that has its historical roots in the collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. The party that has systematically fought for an amnesty for Nazi collaborators. The party in which the grandparents or parents of some of the present actual leaders had been condemned by the Belgian State for collaboration with the enemy. Nobody is guilty of sins of their ancestors, but when there is a pattern of such pedigree being considered a great plus for current leadership, and that pedigree is subtly glorified rather than disowned, we have a current moral problem that merits discussion in the public square.