PERSON OF THE YEAR SERIES | LITHUANIA | LITVAK AFFAIRS | HISTORY

◊

by Danutė Selčinskaja

◊

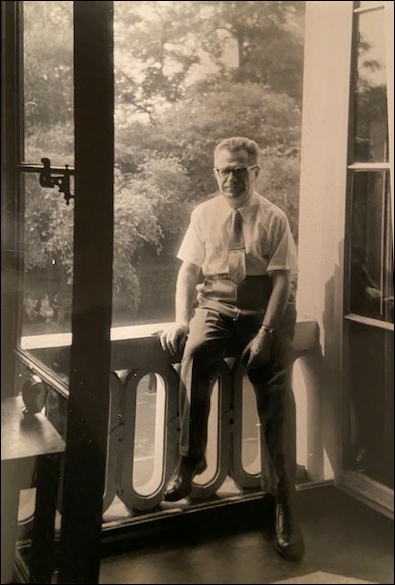

Eminent scholar, author, and Holocaust survivor Berl Kagan, often known as Berl Kahn (1908-1993) renowned in his pre-war Lithuania youth as a scholar, lecturer and editor (of the newspaper Dos Vort), worked after the war in New York at the Yivo (Yiddish Scientific Institute, later Yivo Institute for Jewish Research) from 1954, is widely known for his concise encyclopedia of Jewish towns in prewar independent Lithuania, the final volume of the encyclopedia of Yiddish literature plus a volume of addenda, and numerous other works that are regularly consulted in our third decade of the twenty-first century. Fewer people, perhaps, are aware of his much more deeply personal work, A Yid in Vald (A Jew in the Forest), his Holocaust memoir.

While hiding from the Nazis and their local henchmen in the Lithuanian forests, he felt the need to record what he, his wife Raya, and his wife’s sister Nechama had to endure in the Kovno Ghetto and, from 1943, hiding in the barn of the inspirationally courageous peasant Tadas Pocius (known to friends as Tadeush) in Karalgiris village and, later, in the woods outside the Pocius family’s farm. Since there was no paper to write on, Kagan would write in between the lines of a paperback that he carried with him. In 1955, based on these clandestine records, Kagan published A Yid in Vald. After his death, his daughters Ada Kagan and Miriam Kagan Lieber ensured that the book would appear in English translation A Jew in the Woods.

Defending History’s Person of the Year series

Kagan’s unique testimony of the Holocaust, his his diary of the years in hiding, is multifaceted. It covers the traits of famous and less-famous personalities of the Kovno Ghetto, events in the ghetto, the state of permanent fear that haunted the imprisoned Jews (Kagan calls the ghetto, as well as other Nazi-established extermination camps “valleys of death”), frequent massacres of ghetto prisoners, the pain of bereaved Jewish mothers who had lost their children, his own risky decision to flee the ghetto, and reflections on why it was so hard for the ghetto prisoners to make this decision — to look for hiding places outside the ghetto, to leave the relatively safe zone of their prison: for better or for worse, the ghetto would still provide them with a “roof over their heads” whereas outside it, one was at the risk of death every minute. The risk of being recognized and betrayed.

In his diary, Berl Kagan writes:

In the second half of 1943, the Jews in the Slabodka ghetto lost any remaining illusions they still might have had that they would survive Hitler’s reign […].

Jewish organizations, political parties, individuals, feverishly began making plans. But escape to where? There were only two possibilities: the forest or the countryside. The former meant joining the partisans; the latter meant finding a peasant who would provide a hiding place. The organizations were thinking mainly about the former alternative; individuals, about the latter […].

A close friend of mine, who had a good opportunity to leave the ghetto in time, could not find the inner strength to leave the “comforts” of the ghetto (there were even some of those) and when he did finally decide to act, it was too late.

(Berl Kahn, A Jew in the Woods, Introduction)

The ghetto prisoners are haunted by heavy thoughts on the relationship between Jews and Lithuanians, elementally changed by the Nazi occupation. Everybody knows about the Kaunas pogroms of the earliest days of the war. No Jews remain in the smaller towns anymore. Whom to trust, where to find the people who would accept the ghetto fugitives for an indeterminate time and provide them with food and shelter? As the situation in the ghetto is becoming more and more ominous, most of its prisoners start to realize that, sooner or later, the ghetto would be liquidated, and its inhabitants exterminated. More and more of them start searching for trustworthy people who would agree to take the risk and start hiding a Jewish person or family.

In late autumn, 1943, eight Jews from the Kovno ghetto, including Berl Kagan, his wife Raya, and Raya’s sister Nechama, take the opportunity to go intohiding in Karalgiris. Antanas Volskis, a resident of Karalgiris and initiator of this rescue operation, suggested that his pre-war acquaintances Dovid and Fania Feinberg leave the ghetto and come to this remote village for hiding. The Feinbergs are accompanied by several other people, including the Kagans, and a group of eight people in total is formed with the simple confidence that they will be reliably hiddren by the group of Kalgiris peasants.

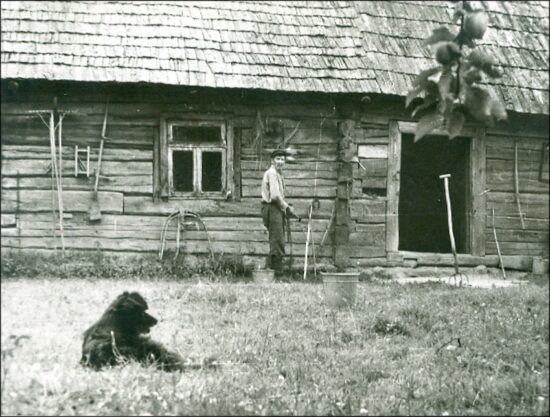

Karalgiris is a forest village. Once upon a time, people moved there, cut their plots in the brush, and built their houses. No neighbors can be seen from the houses, only alders, little birches, and feeble firs. The village, massive in area, begins thirty kilometers from Kaunas and continues along both sides of the Žemaičių Road which heads out toward the Kaunas and Kėdainiai districts.

Since the Volskis family homestead is at the edge of the village, it is quite visible was not suitable for prolonged hiding of Jews. So, Antanas Volskis made an agreement with Tadas Pocius and his wife Barbora, who live at the “deep end” of Karalgiris, in a homestead hidden by dense bushes, that they will accept the Kovno Ghetto fugitives in their home, and the Volskis family will help them provide food for the Jews. On October 20–24, 1943, Tadas Pocius made two return trips (around forty kilometers one way) and, under cover of night, ferried eight Jews in his cart all the way from the Kovno Ghetto to his homestead: Dovid and Fania Feinberg; Berl and Raya Kagan; Raya’s sister Nechama; Moshe Achber; and Shléyme (Shelomo) and Tamara Goldstein.

◊

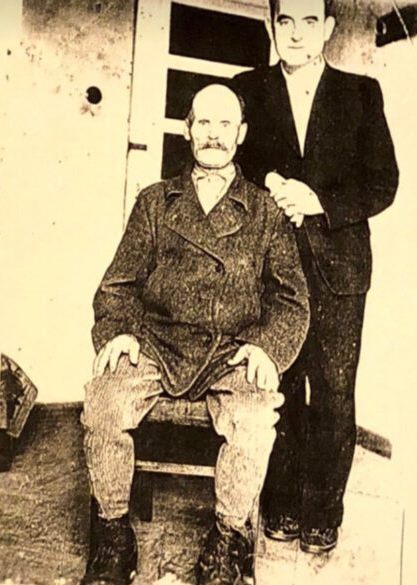

On Rescuer Tadas Pocius

Here is how Berl Kagan describes the trip from Kaunas to Karalgiris:

Who can really describe the anguish of a person who is about to take a life-or-death leap? Forty kilometers we had to cover before we would reach our hiding place in Karalgiris, near Vilki. How many times will death be lying in wait for us? […]

We’ve been riding now about ten hours, often plodding through the deep mud of a remote Lithuanian road on a half-frozen night in October. For the horse, every step is forty pounds. Very frequently he gets stuck. The trip seems endless, but the driver keeps reassuring us: “One more kilometer.” But we have already traveled ten of these “one more kilometers”

(Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, diary entry for October 20, 1943)

When they reach Tadas Pocius’ house, his wife Barbora meets them:

She (Barbara) kisses my wife and my sister-in-law with real affection.

Here you’ll be treated like my own children […] The women burst into tears. I can barely refrain from crying myself. My heart almost stops at this extraordinary sight: a complete stranger, embracing and kissing two Jewish women! In these days.

(Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, October 20, 1943)

Several days later, five more Jews travel this difficult road from Kaunas to Karalgiris. While the guests are sharing news from the ghetto in the tiny Pocius house, Tadeuš anxiously interrupts their conversation:

“Where am I going to put you all?” One of us tries to anticipate him: “Well, we’ll try to find another place and divide ourselves up.” To which he replies: “Yes, yes, but there aren’t that many good people around here.” […]

“We’ll manage somehow. Almost all of you are young. You still have a life to live. I’m not doing this for the money. I’m pretty old myself. I won’t take the money with me into my grave. I just don’t want to see any more innocent blood spilled. If I could, I would save more Jews. But since I can’t, I’ll protect those that I can. I want to show you that not all Lithuanians are like those partisans of ours.”

(Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, diary entry for October 25, 1943)

Since it is not possible for that many people to hide in the tiny house and barn of Tadas and Barbora, Moshe Achber is accepted to the home of fellow Karalgirians Leonas and Stanislava Vaidotas, and Shléyme and Tamara Goldstein find shelter in the neigboring village of Lelerviškiai, at the home of Teresė Danilovič.

A big problem while hiding at the Pocius home is the constant shortage of food. The Pocius family lives in poverty and they can barely feed themselves. Although Antanas and Stanislava Volskis try to keep their promise and bring some food from time to time, it is not enough. The situation is made worse by people whom Kagan identifies only as Mr. and Mrs. F. in his diary, who feel privileged and refuse to share their food with the Kagans, therefore the latter often go hungry and tension between the fugitives keeps growing.

◊

An unexpected threat arises when a note with Antanas Volskis’s address is found at the place of Moshe Achber’s brother, who was hiding in Kaunas.

Volskis is arrested by the Gestapo and brought to Kaunas for interrogation. For several days, everybody in Karalgiris is fearful that Antanas may be tortured and would give out their hiding spots, but he manages to prove that he has nothing to do with any Jews and, after several days, comes back to Karalgiris. After this incident, the Vaidotas family, fearing consequences, build a temporary hideout for Moshe Achber in the woods. Every night, Leonas Vaidotas’s son Česlovas brings him some food, but it is very difficult for a single person to survive in the woods in such conditions, and, after a while, Moshe comes back to the Pocius household.

In his diary, Berl Kagan notes a memorable song, created by Moshe Achber while hiding in the home of Tadas and Barbora Pocius:

- In a far corner of the Lithuanian land

- I stand on watch with a rifle in my hand.

- A community of Jews who numbered eight.

- Guarding against death by men of hate.

- They guard us — our two sentinels —

- He is seventy, and sixty is she.

- And their dog, he too stands guard,

- As does the vast dense forest.

- Two old people with the blood of heroes

- who hate the Kubiliunas killers.

- Out of righteousness they further weave

- the human dream of friendliness to Jews.

- ◊

- (Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, diary entry for October 30, 1943)

◊

For ten months, Tadas Pocius and his wife Barbora share their meager food supplies with the Kagans. Whenever a threat seems imminent, they move them into the woods, where the fugitives suffer horrible cold and fear of being found or betrayed; more than once, they find themselves on the brink of total exhaustion. Their only hope and consolation is Tadas Pocius, who, walking in circles to confuse anyone who would follow his footprints in the snow, keeps visiting them with pots of hot broth that are specially made by Barbora.

Only the immense and sometimes simply unbelievable efforts of both the rescuers and the fugitives in hiding, as well as endurance of all involved in this story, make it possible for the eight Kovno Ghetto fugitives to await the day of liberation in Karalgiris.

But the joy of liberation is darkened by the sorrow of having lost their close ones:

The shadow of death had pursued us and we kept running away from it with every bit of our strength. We never looked back, although running blindly, when we had lost mother and father, brothers and sisters, friends. In the fear of death and in the delusion of death we had leapt across their dead bodies.

Now that its shadow had suddenly fled, the Angel of Death had disappeared, and with it, had gone the momentum which had carried us on its wings for weeks, months, years, and now we suddenly saw them all clearly: parents — dead; brothers — dead; sisters — dead; friends — dead. All at once there rose before our eyes the horrible image of three and a half years of Hitler’s ghetto, three years of slaughter, and in all its horror the question hung in the air: “Where are they all now? Where?”

(Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, diary entry for August 3, 1944)

On August 7, 1944, after ten months of living in fear and hope one next to the other, Berl Kagan, his wife Raya, and Raya’s sister Nechama say their tearful farewells to Tadeuš and Barbora.

Ten months! The deadly dangers and the feelings of gratitude created invisible threads of love between us and the old couple. Only during the minutes when we became certain we would live did we begin to feel the attachment to this place, where extraordinary people had saved us from death. Even the broken down old cottage and the crumbling barn became dear to us, as did the thick bushes, the loyal dog, the horse and more than anything else, the two old Lithuanians. We used call them “Tevialis and Mamita” (Little Father and Little Mother), but only now do we become aware that these were not idle words. They were a reflection of feelings whose genuineness we did not understand until the moment of separation.

(Berl Kagan, A Jew in the Woods, diary entry for August 7, 1944)

From left to right: Barbora, her daughter Benedikta Bundzienė, grandchildren Povilas and Roma, and Benedikta’s husband Jonas Bundza (Karalgiris, 1970)

◊

All the players in this narrative have left this world a long time ago, but, due to Berl Kagan’s efforts to record what he and his close ones had to endure during the Holocaust, the story itself will not be forgotten.

In 2021, at the suggestion of the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History, the Karalgiris peasants Tadas Pocius and Barbora Urbonavičiūtė-Bacevičienė (Pocienė), Antanas and Stanislava Volskis, and Leonas and Stanislava Vaidotas were awarded the Award of the State of Lithuania: The Life Saving Cross, for rescuing eight Jews from the Kovno Ghetto. The crosses were awarded to the grandchildren of the rescuers of Jews by the president of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda.

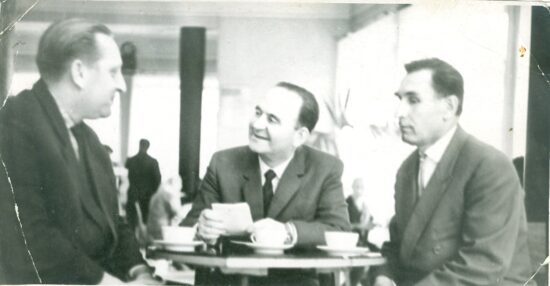

We would not have achieved this without the sincere support and help of Miriam Kagan Lieber and the Kagan family member and its history researcher Marc Katz. Their help in undertaking a close reading of Berl Kagan’s diary, identifying rescuers, and searching for their descendants in all corners of Lithuania was invaluable. We are pleased to be able to let it be known that the search for the rescuers’ descendants was successful.

Miriam, daughter of Berl Kagan, and Roma, granddaughter of Tadas and Barbora Pocius, are now friends.

We hope that, one day, Berl Kagan’s unique diary A Yid in Vald (A Jew in the Woods) would be translated to Lithuanian and become accessible to all inhabitants of Lithuania interested in their country’s history and heroes.

Danutė Selčinskaja is head of the Project for Commemoration of Rescuers of Jews at the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History.

◊