O P I N I O N

by Michael Shafir (Cluj-Napoca, Romania)

1. Approximately when did the drive to equate the Holocaust and the sufferings endured by people under Communist regimes start?

It is very difficult to pinpoint an exact date. In the West, a number of Sovietologists have long driven attention to the fact that the horrible crimes perpetuated by Stalin and his henchmen in East Central Europe deserved the attention and the opprobrium that Nazism met with after the Second World War. Due to Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s famous book Gulag, these crimes soon began to be referred to under the synthetic name of that book. The collapse of the Communist regimes in the region in 1989 and the implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991 intensified that drive, which also found an impulse in the once popular (but later criticized) “totalitarian model.” That model was now revived, finding support particularly in the eastern part of Europe that had suffered under Soviet domination. Western historians were (and still are) quite divided over this issue. For example, Robert Conquest, who produced several important books on Stalinist crimes, was reluctant to place the Holocaust and the Gulag on the same footing. On the other hand, Stéphane Courtois, who edited and contributed to the Black Book of Communism, not only embraced the comparison, but insisted on

Yehiel (Yekhíel) Zilberman was born in Lithuania in 1922. In 1940 he graduated from the H. N. Bialik Hebrew High School in Shavl (Šiauliai) and was admitted to the Institute of Commerce in the same city. In June of 1941, one year after Lithuania fell under Soviet rule, Yehiel along with his parents and brother Moshe (Mikhail) was exiled to the Altai Region in Russia where he lived until 1945. In 1949 he graduated with Honors from Gorky Industrial Institute and became a chemical engineer. Yehiel worked in both manufacturing and scientific research. In 1954 he received his PhD from the Moscow Institute of Chemical Technology. In 1965 Dr. Zilberman received the title of Professor. From 1970 to 1990 he taught at Gorky Polytechnic Institute.

Yehiel (Yekhíel) Zilberman was born in Lithuania in 1922. In 1940 he graduated from the H. N. Bialik Hebrew High School in Shavl (Šiauliai) and was admitted to the Institute of Commerce in the same city. In June of 1941, one year after Lithuania fell under Soviet rule, Yehiel along with his parents and brother Moshe (Mikhail) was exiled to the Altai Region in Russia where he lived until 1945. In 1949 he graduated with Honors from Gorky Industrial Institute and became a chemical engineer. Yehiel worked in both manufacturing and scientific research. In 1954 he received his PhD from the Moscow Institute of Chemical Technology. In 1965 Dr. Zilberman received the title of Professor. From 1970 to 1990 he taught at Gorky Polytechnic Institute.

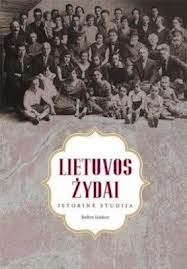

On Friday, September 13, 2013, the Baltos Lankos publishing firm in Vilnius held a discussion at their main book sales outlet in Vilnius to present a book edited by Professor Jurgita Verbickienė about the Jews of Lithuania.

On Friday, September 13, 2013, the Baltos Lankos publishing firm in Vilnius held a discussion at their main book sales outlet in Vilnius to present a book edited by Professor Jurgita Verbickienė about the Jews of Lithuania.