O P I N I O N / R E V I E W

by Birutė Ušinskaitė

Cover of playbill

It was just another rainy and not overly cold evening in early December of the year 2011, but the play I was privileged to see at the Kaunas Chamber Theatre, Day and Night, proved to me, a proud Vilnius native and resident, that not all that is bold and brilliant originates in our capital.

For the first time in modern Lithuanian history, in my experience at any rate, a Lithuanian play on the Holocaust did not try to deflect attention ― or responsibility ― to the Germans or to some pseudo-objective forces of society, or to stick to some “kosher” theme like the dilemmas of Gens and the Judenrat in the Vilna Ghetto in order to avoid talking about what is frankly the main point for our country: the voluntary participation of many of our countrymen in the mass murder of the Jewish citizens of our own country, in some cases before the Nazis even arrived.

For the first time in my life, I have been able to enjoy a quality literary creation where the barbaric and pathologically racist and fascist nature of some members of the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) is shown exactly for what it was. In Lithuanian, by and for a Lithuanian audience. That makes me proud.

It is a small theatre, and there were perhaps only a hundred people present, but it was in its own way a grand national catharsis that makes me as a born and bred Lithuanian citizen very patriotic in the European sense of the word, where patriotism is loyalty to finding out and facing the truth and not some kind of nationalist whitewash or prejudice toward minorities.

Day and Night is a signal that at long last we are becoming a mature nation where a theatre production can finally portray the simple truth that some of these LAF heroes were murderers of civilians, spreading hate toward fellow natives of their country. That it was done artistically, with a strong and unforgettable scene of two LAFers wrapping the white band around their new colleague ― not with some righteous declaration ― made it all the stronger.

The artistic director is Stanislovas Rubinovas, the Chamber Theatre’s founder. The play was supported by the Cultural Support Foundation of the Republic of Lithuania, also by the Lithuanian Jewish Community and the Kaunas Jewish Community. The duration of the two-part play is two and a half hours. I personally found that on the long side, and it could benefit by condensing and consolidation of some of the latter scenes. The other thing is the choice of the music by composer Faustas Latėnas. In my opinion, Yiddish popular songs were not exactly the best choice. I think that Yiddish folk songs from Kaunas, and songs from its wartime ghetto, would have made the play more authentic. Everything else seemed to be almost perfect from the subtle make-up of the actors, the traditional Jewish costume to the lighting effects. The lights dimmed at the beginning of the scenes conveyed a slowly unfolding horror.

Even though the characters of the play have no real prototypes, the plot is based on historical facts, testimonies of witnesses and archival documents from the Holocaust era. The actors even read some of the documents aloud and quote them in their dialogues, like, for example, one antisemitic article from a newspaper. Naturally, some viewers might not understand the significance of the play and why it is necessary to speak about the Holocaust in Lithuania today, so they would naturally want to raise the question why this play was ever written.

As playwright Daiva Čepauskaitė puts it:

“I was searching for a serious and principled topic. And the Kaunas Chamber Theatre suggested that I should write about the Holocaust in Lithuania. I took this as a challenge, both as a playwright and as a human being. It was a really difficult task for me as a professional ― it was difficult to find the right language, form and the way to tell the story. But the topic enriched me as a person; I had an opportunity to come up with certain principles and a personal approach. Therefore, I have an answer to the question why I have written this play: I wrote it because I am Lithuanian, because it is our common history and because I do care about things that happened, are happening or will happen in Lithuania. And because it hurts.”

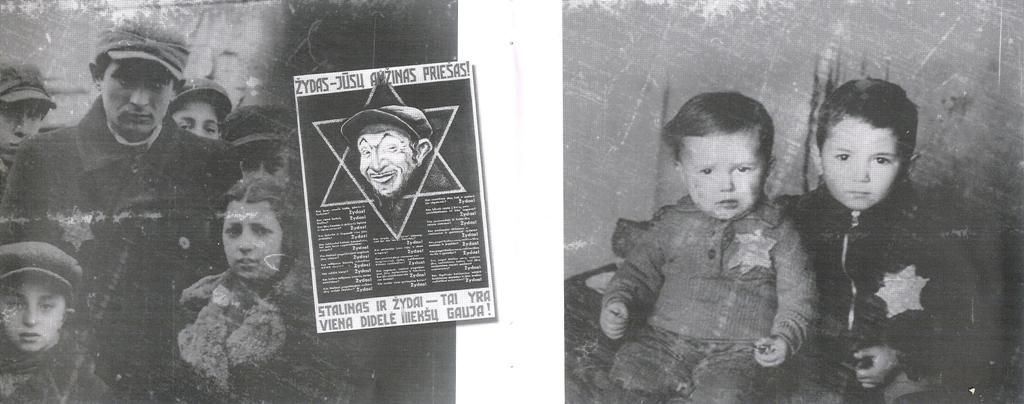

From the playbill: Period photos and a 1941 poster tell the audience that this will be no whitewash. Another page has a 1941 photograph of an undressed-for-murder woman being shot in the head by a ‘partisan’.

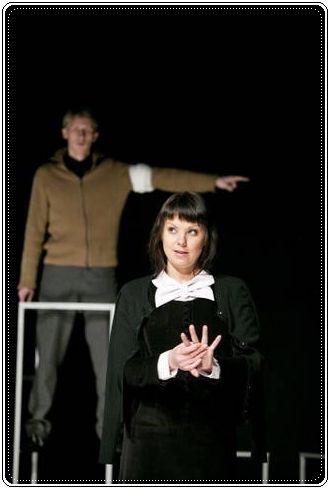

It is a tragic love story, the impossible love of teenagers ― a Lithuanian boy Andrius and a Jewish girl Milda, who are playing a strange game. The main characters are played by young and talented Lithuanian actors: Simona Bladženauskaitė and Vytautas Gasiliūnas. Andrius and Milda invent a strange game. They are playing out the Holocaust in Lithuania and acting out the love story of Milda’s grandmother Golda, who is now old and not clear of mind. Golda had in fact gone mad when her lover Kostas accidentally got shot right before the end of the Second World War, when Golda turned nineteen. It seems that Andrius and Milda are unable to live their own lives; they are the incarnations of the ghosts of the past. Sometimes Andrius resists Milda’s wish to live in the past, but then she starts numbly counting aloud to herself and he invariably succumbs.

It seems to me that very many people in Lithuania cannot calmly live and roam the streets of the old ghetto in Vilnius, Kaunas and Šiauliai without getting possessed by the dybbuk of the past. In order to let the old wounds heal and to prevent the horrors from happening once again, it is important to tell the young generation of Lithuanians what we have done to our neighbors. Therefore, it is significant to speak about the reasons and the preconditions of the Holocaust in Lithuania, as well as about the lamentable antisemitism today.

The author explains:

“When I was writing the play, I was reading some documents in the archives, and one protocol of the court caught my eye. The defendant was asked why he was murdering the Jews and he replied “because I am Lithuanian”. Then I thought about the many meanings of this word. After all, those who rescued Jews were also Lithuanians. The same word can mean the most honest fight for the freedom of the people, simple humanity, or the lowest instincts. I am also Lithuanian and I wrote this play […] because life and death have no nationality, and because inhumanity is our common enemy.”

The two timelines of the play are looping. Today’s reality intertwines and intersects with the past, and those intersection points are exactly the most important ones and the ones that hurt like wounds which never healed. And the wounds and the pain are real ― Kostas burns his arm badly in order to be able to see Golda, the Jewish girl, with whom he falls passionately in love. He comes on Friday night and Golda has to violate the Sabbath law in order to help him, because Jews are not allowed do any work on the Sabbath. Golda’s father Berelis Taicas, a pharmacist, explains to Kostas what it means to be a Jew – the Jewish happiness is a very short time between long periods of unhappiness and misery, which change like day and night. Berelis Taicas says that God has punished him, because he has no son, only two unmarried sisters and three unmarried daughters, and, even worse, he thinks that one of the daughters is too smart for a girl, so he cannot feel happy.

Then the war breaks out and everything changes, at least for the Jews. The Red Army withdraws from Kaunas and massacres of Jews start immediately. On 25 June the German advancing troops (Vorauskommando) enters Kaunas. The situation is horrible. The infamous massacre of the Jews takes place in Lietūkis garage in Kaunas on 27 June 1941. It seems that the earth catches fire underneath people’s feet. The gang of Klimaitis rages and murders people, some Jews are burned alive. One can smell the fear in the air and some Jews are trying to escape or go into hiding. On 12 July 1941, a regulation is issued for the Jews to wear a yellow star, 8-10 cm width in diameter on the front and on the back. They are not allowed to leave home after 8 PM. Then another regulation sets out that Jews have to leave their homes and move into a Ghetto in Vilijampolė by 15 August. In Kaunas, Jews are taken to the 7th Fort. Almost all of them are gunned down mostly by volunteer Lithuanian gunmen. Some of them are nowadays sometimes hailed as “anti-Soviet patriots”. Moreover, the Provisional Government of Lithuania does not say a word to condemn the ongoing massacre. After five weeks the mass graves of the victims near the Kaunas 7th Fort start to cause problems. The local inhabitants start to complain about the bad smell. In the second half of July it is forbidden to swim in the Nemunas and the Neris Rivers because it is believed that the water is contaminated with the “poison of the corpses”.

Kostas joins the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) together with his friends, who instigate racial hatred and antisemitism. Kostas becomes a Jew-killer, but he saves Golda. Golda’s father is taken away by the young guys who are wearing white armbands. He never comes back. Golda finds shelter in a hiding-place, a pit under the floor of his house. By day Kostas and his friends murder other Jews, because their task is to liquidate all the “Communists” and Jews though it is Jews who are declared the enemy. By night he makes love to Golda.

Once Golda inquires of him whether he had shot many of their neighbors and Kostas replies that he had murdered all of them, so that nobody would interfere with their love. Golda attempts suicide, but later she finds out that she is pregnant. One night, after giving birth, she is allowed to have a little walk in the garden. She looks at the starry sky and screams: “Oh, God, the sky is full of Jews! They all are there!”

There are good times and there are bad times in every nation’s life, just like there is day and night, and sometimes we make things of which we cannot be proud of, but the story of the Holocaust in Lithuania seems to be the darkest page in the country’s history. Even today it is difficult and painful to speak about this issue. Discussions are overheated, harsh and overloaded with emotion. Therefore, it is very difficult to maintain a straight and open dialogue.

However, the creators of this play, perhaps for the first time in Lithuania’s history, managed to examine and analyze this topic with full honesty. They are not trying to solve any historical dilemmas. Their only goal is to frankly and bravely tell what really happened and what made this tragedy possible. And this is very important, because it gives hope for all of us to open a sincere dialogue about the issues of the past.

The scenes from today actually do more than serve the literary purpose of incarnations of old souls emerging among us. They are a blunt warning about the possible advent of antisemitism right here and now.

This very strong play can and should be translated into English and other languages and shown abroad.

It will do Lithuania proud.

Diena ir naktis.

KAUNO KAMERINIS TEATRAS.

Directed by Stanislovas Rubinovas. Art: Sergėjus Bocullo. Music: Faustas Latėnas.

Starring Simona Bladženauskaitė and Vytautas Gasiliūnas; Alma Masiulionytė, Aleksandras Rubinovas, Violeta Steponkutė; with Kristina Kazakevičiūtė, Daiva Škelevaitė, Asta Steponavičiūtė, Edita Niciūtė.

Birutė Ušinskaitė is a Vilnius translator and memoirist.

Note: This article was republished without permission or accreditation in VilNews.com. DefendingHistory.com is delighted to grant permission for republication with simple accreditation and provision of the link to the original.