O P I N I O N

by Pinchos Fridberg

Some facts

In 1998 the “International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupational Regimes in Lithuania” was established by Lithuanian presidential decree.

The commission is directed in tandem by Emanuelis Zingeris and Ronaldas Račinskas. The former is the commission’s chairman and a Conservative MP in the Lithuanian Seimas, while the latter is the commission’s executive director. The Lithuanian Jewish Community has no representation on the commission.

Foreword

At the European forum “United Europe: United History” on November 16, 2012, I was an eye-witness to the report by Mrs. Vilkienė, deputy director of the commission and coordinator of its Educational Programs section. This is how she was presented by the moderator, Dr. N. Šepetys, who added: “She has led history teachers to rationality, encouraged them and forced them to think.”

The forum included representatives from EU countries and Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova and other countries.

The final part of Mrs. Vilkienė’s lecture made such a deep impression on me (unfortunately, just me) that I decided to produce the transcript. Not a single word was omitted from the transcription. This is easily verifiable by listening to the audio file (in Lithuanian). This process takes just 4 minutes and 57 seconds.

Transcript of Mrs. Vilkienė’s speech

(translated from Lithuanian)

I just want to [give] only one example, without slides.

Around a year ago I was invited to come to our Tolerance Center which is in Telšiai at the Bishop Borisevčius Gymansium. They organized a conference together with the Telšiai Priests’ Seminary. The conference marked 70 years since the destruction of the Telšiai ghetto. Well, of course Telšiai is very far, I took along one colleague from Vilnius, from Viršuliškės, from another Tolerance Center, and we decided to see what of interest our good Telšiai teachers would in the end present. The conference as you know, as here, had many papers, some interesting one, some not-so-interesting ones.

About 200 to 300 students took part in the conference, there were many, many of them, from all the schools of Telšiai, from the high school, and very many teachers.

Well, already by the second half of the day it was sufficiently boring, everyone was, you know, tired already. A woman came on stage, an elderly woman, let’s call her a senior citizen, who took a page and began to read in an uninteresting way what was written there, that I am the daughter of so-and-so, who rescued Jews, and, well, a sort of lecture, in the tone of a lecture there she was reading something. I was sitting next to the priest and asked: Why is she reading, why isn’t she telling her story, her dad’s story? And it was as if she didn’t hear me really, but she after some time reading what she had written, since she was really nervous, she set the page down and began to tell the story. There was noise in the hall at that point, because the hall was totally full. When she began to tell the story the entire hall fell silent and I was standing there the same way and, I wasn’t standing, but I was sitting and listening directly, so fascinated since this was such an interesting story.

And the story was that in ’41 after the Nazis decided to set up a ghetto in Telšiai, her dad, who was about 30, 32, 35 years old and who was married and had a wife, who was pregnant, pregnant namely with this woman who spoke last year. When her mom was still pregnant with her, [they/he] decided to rescue Jewish neighbors, and there were many of them living there in the area around their house. That is, it was a small village. Together with another neighbor, they decided to save two Jewish families. But since the home of this woman, whose father rescued [Jews], was further back near the forest, they decided it would be best to hide them here.

And what did they do?

They dug a huge, huge bunker, a giant pit, and took 43 Jews, their neighbors. And they hid them from ’41 till ’44. They hid them, while in fear of their neighbors, every night opening that bunker, letting them breath fresh air, taking care of food, they themselves not being very well-off. During that time a girl was born in the bunker. That means they rescued 44, not 43.

During that time the pregnant woman, the wife of the rescuer, also gave birth to this woman who was telling us this story. And she told it so simply, as a simple matter: as if it were self-evident: they rescued people. And we, we who, who then stood, that is, sat in the audience and listened, we thought: Well, how did they take care of food, during winter, clothes, hygienic conditions for three years, how were people able to do that?

And that story, I believe, taught [us] much, very many things, first about the ability to help, about aid to others, about victims, those who were hidden, about those who tried to find those people, that there is a story about these people, that they, four people, are the ones who rescued two families, they were afraid to ask others for help because they thought they would turn them in. And really there are so very many moral matters. So I think that these stories, this is a personal experience of history, it is very important.

And, of course, research which our commission’s historians are performing is very important! It is very important to know the numbers! Very important, and, and, really, that historical objective truth, it is very important!

But the personal relationship, whether we are talking about one occupation or we are talking about the other occupation, is really endlessly important. I myself believe that, I, believe, that some of you are also thinking about that. And I wish everyone success and a good tolerance day.

* * *

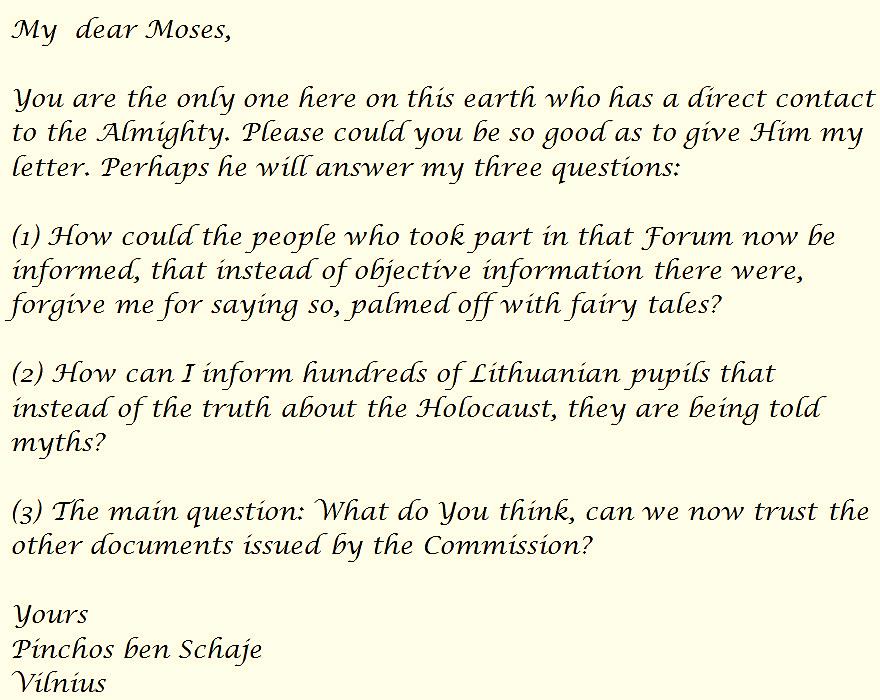

An Old Vilna Jew’s Letter to Moshe Rabbeinu

Translation from Yiddish:

P.S.

1. At my request, Borisas Gelpernas transcribed the contents of Mrs. Vilkienė’s report (from a DVD containing the proceedings of the forum, which I have).

His father Dmitrijus Gelpernas (1914 ― 1998) was an inmate of the Kovno ghetto from 1941 to 1944, was assistant secretary of the antifascist organization’s committee and from July of 1944 until liberation an inmate at the Dachau concentration camp. His mother Sulamif Gelpernienė-Lermanaitė was also a Kovno ghetto inmate.

2. Unlike Mrs. Vilkienė, who delivered a report for her commission, I only express my own opinion and that of my wife, a former Kovno ghetto inmate. My grandmother and grandfather, a host of my relatives on my mother’s side, all lie at Ponar (Paneriai). The memory of them and of about two hundred thousand innocent compatriots who were murdered provide me the strength to scrupulous contradict supposed facts that have nothing in common with the discipline called History.

3. I can think of no better advertising for the commission than the distribution of the production it has published: the transcript will see the light of day in five languages—Lithuanian, Russian, English, Hebrew and Yiddish. A video clip in these same five languages will appear on Youtube, tentatively titled “I just want to show one example, without slides.” I will invite people in show business with Jewish roots from around the world to read this text before the camera in Russian, English and Hebrew. I hope they will do this as a mitzvah, an act of goodness. I myself will deliver the text in the máme-loshn, my native Yiddish language.

P. P. S.

At the close of the advertising campaign, I plan to employ the sage advice of former Baltic News Service director Artūras Račas: “Dear Pinchos, who calls himself ‘professor,’ stick a gag in your mouth, get under the table and shut up.”

Until someone gets the bright idea again to create another one of these “histories,” I’ll take his advice.