Defense of Old Jewish Cemeteries and Mass Grave Sites

When the Lithuanian Prime Minister Interrupts his Schedule to Greet Some Very Non-Litvak Rabbis from London

Joseph Levinson’s Symbolic Gravestones for His Parents “Speak Out” During His Own Funeral (12 April 2015)

C E M E T E R I E S / P H O T O G R A P H Y

by Dovid Katz

◊

◊

◊

As dozens gathered at Vilnius Jewish cemetery to bid farewell to dear Joseph Levinson today, those who read Yiddish could not fail to notice the two symbolic gravestones he erected on the family plot, in Yiddish by choice.

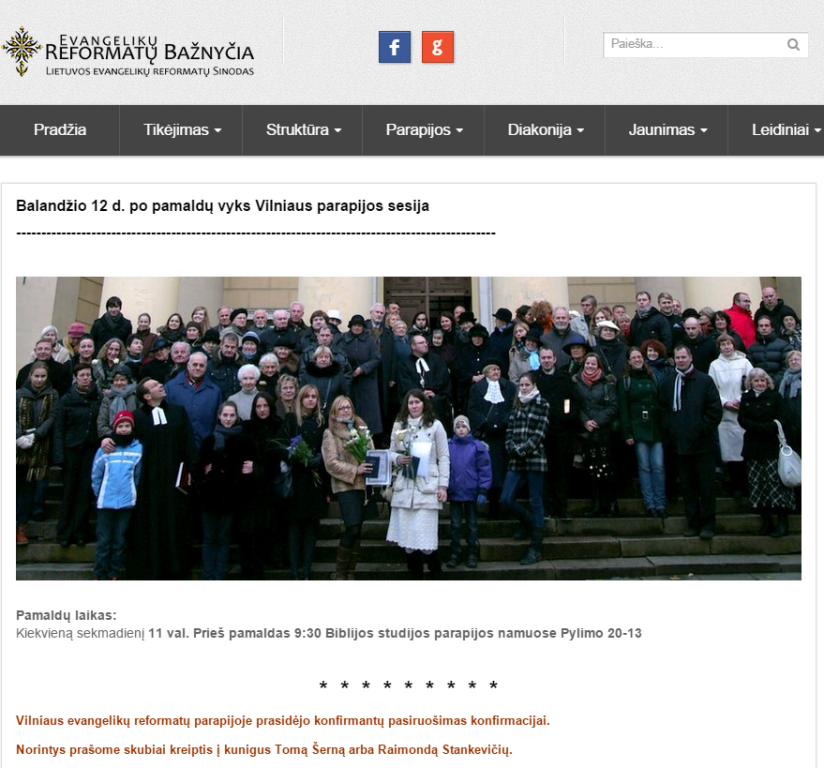

Advertisement for Church Service Flaunts Congregation Stepping on Old Jewish Gravestones

CEMETERIES / REFORMED EVANGELICAL CHURCH / CHRISTIAN-JEWISH RELATIONS

◊

VILNIUS—The website of the Reformed Evangelical Church services this weekend advertised today’s Sunday service with a previously-made photo of pastors and worshippers posing for a photograph with their shoes pressing into the pilfered Jewish gravestones, some of which still have visible writing, of which the steps to the church are made. The church has still issued no public statement on its retention of the Soviet-era made-of-pilfered-Jewish-gravestones steps even after its much-celebrated reconstruction and restoration less than a decade ago.

◊

Joseph Levinson (1917-2015)

Stated Purposes of Lithuanian Government’s New Commission on Jewish Heritage

D O C U M E N T S

◊

The following excerpt from the Lithuanian government’s documents, released today, explains the purposes of the new state commission on Jewish heritage. It is excerpted from longer documents available here and here. Updates on the commission’s history will appear on this page.

The Lithuanian Government’s New Commission on Lithuanian Jewish Heritage

D O C U M E N T S

The following English version of the Lithuanian government’s announcement of its new state commission on Jewish heritage was released today. A PDF of the entire document is available here. An excerpt containing the mission statement is available here.

Annual Memorial for the Jews of Svintsyán (Švenčionys): Small but Well Done

by Defending History Staff

Svintsyán [Švenčionys] — Some fifty people gathered in the forest at midday today at the mass grave at Poligón, outside Švenčioneliai (Yiddish: Svintsyánke), in northeastern Lithuania, where around 8,000 Jews were murdered on 7 and 8 October 1941 after more than a week of barbaric incarceration and humiliation. The number includes nearly all the Jews of the county-seat town Švenčionys (Svintsyán) as well as the Jewish citizens of a number of towns and villages in the region, including (Yiddish names first in the following list, followed by current Lithuanian or Belarusian names): Dugelíshik (Naujasis Daugėliškis), Duksht (Dūkštas), Haydútsetshik (Adutiškis), Ignalíne (Ignalina), Koltnyán (Kaltanėnai), Kaméleshik (Kimelishki, Belarus), Labonár (Labanoras), Lingmyán (Linkmenys), Líntep (Lyntupy, Belarus), Maligán (Mielagėnai), Podbródzh (Pabradė), Saldúteshik (Saldutiškis), Salemánke (Salamianka), Stayátseshik (Stajotiškės), Svintsyánke (or Nay-Svintsyán — Švenčionėliai), and Tseykín (Ceikiniai).

Misha (Meyshke) Shapiro (at left), head of a region’s tiny remnant Jewish community, chairs the annual commemoration in the forest at a mass grave where 8,000 Jews were killed in two days in October of 1941.

Yankl-Yosl Bunk – Jakovas Bunka (1923 – 2014)

Yankl-Yosl Bunk (Jakovas Bunka), Famed Wood Sculptor, Last Jew of Plungyán (Plungė, Lithuania), Dies at 91

His Art Commemorates the Holocaust in Western Lithuania

Was World War II Red Army Veteran of the War Against Hitler

The Stones Tell Me. After All, They Lived Here.

O P I N I O N

by Genrich Agranovski

Genrich Agranovski is co-author (with Irina Guzenberg) of Vilnius: Sites of Jewish Memory as well as other works on Jewish Vilna. This comment was translated from the Russian by Ludmila Makedonskaya. See also DH’s section on old Jewish cemeteries and mass graves.

At the beginning of the 1990s a commission tentatively called “Memorial” was founded at the Jewish Community of Lithuania. Its aims included collecting information about the mass murder and burial sites of the World war II period, Jewish cemeteries, as well as other issues connected with the memory of the perished. The commission was headed by Joseph Levinson. Being a member of the commission, I was in charge of collecting information on Jewish cemeteries in Vilnius. There had been two large Jewish cemeteries in Vilnius before the war: the “old one,” founded, according to Vilna Jewish lore, at the end of the fifteenth century and used till 1830, and Zarechenskoye [“beyond the river”; in Yiddish Zarétshe] (Antokolskoye), which was used from 1828 up to June 1941. The latter was the biggest in the city. According to the Jewish ethnographer Solomon Shik, seventy thousand people had been buried there by 1937. In Soviet times both cemeteries were destroyed and the gravestones were used for construction purposes.

Мне камни говорят — они здесь жили

МНЕНИЕ

Генрих Аграновский

В начале 1990-х годов при еврейской Общине Литвы была создана комиссия, условно называвшаяся «Мемориал», в задачи которой входил сбор информации о местах массовых убийств,захоронений евреев в годы 2-й Мировой войны, еврейских кладбищах и другие проблемы, связанные с памятью о погибших и умерших евреях. Комиссию возглавил Иосиф Левеинсон. Я, как член комиссии, отвечал за сбор информации о еврейских кладбищах Вильнюса. До войны в Вильнюсе было два еврейских кладбища-Старое,основанное по преданию в конце 15-го столетия и действовававшее до 1830 года, и Зареченское (Антокольское), действовавшее с 1828г. вплоть до июня 1941 года. Последнее было самым большим в городе-на нем ,по данным еврейского краеведа Соломона Шика, до 1937 г. было похоронено 70 000 человек. В советские времена оба кладбища были разрушены ,и могильные камни были использованы для строительных целей.

New Joseph Levinson Website Has Page on Old Jewish Cemeteries in Lithuania

The recently launched website JosephLevinson.com provides renewed opportunities for acquiring his two major books that are available in English. One, The Shoah in Lithuania, includes documents of the Lithuanian Activist Front detailing their intentions for Jewish citizens, issued before the outbreak of war on 22 June 1941. It is also rich in resources on understanding how, where and why the far right’s “Double Genocide” revisionism arose in the first place. These are just two of the many areas covered by the book.

Aleksandrs Feigmanis Documents Mysterious Eight-Pointed Star in Riga Synagogue

Following publication last year of an article on the mysterious eight-pointed star known from some old Jewish cemeteries in western Lithuania (the area known as Zámet in Yiddish, corresponding in part to Žemaitija), DH contributor Dr. Aleksandrs Feigmanis, director of Riga-based BalticGen Tours, has reported that a similar eight-pointed star adorns the (recently renovated) synagogue in Riga, Latvia. Hopefully, images will emerge of the prewar design corresponding to the reconstructed section in question.

Following publication last year of an article on the mysterious eight-pointed star known from some old Jewish cemeteries in western Lithuania (the area known as Zámet in Yiddish, corresponding in part to Žemaitija), DH contributor Dr. Aleksandrs Feigmanis, director of Riga-based BalticGen Tours, has reported that a similar eight-pointed star adorns the (recently renovated) synagogue in Riga, Latvia. Hopefully, images will emerge of the prewar design corresponding to the reconstructed section in question.

Where You Have to Step on Old Jewish Gravestones to go to Church

C E M E T E R I E S / C H R I S T I A N – J E W I S H R E L A T I O N S

by Dovid Katz

◊

The following are translated (and edited) excerpts from a longer letter in Yiddish received from a survivor who has asked to remain anonymous, about the Jewish gravestones that form the steps going up to the Reformed Evangelical Church at Pylimo 18 in Vilnius.

Mystery of the Eight-Pointed Western Litvak (Zámeter) Symbol on Jewish Gravestones

by Dovid Katz

On expeditions and on culture and history tours, we have on a number of occasions come across unusual Jewish gravestones (in Yiddish — matséyves), so far invariably on the territory of western Lithuania (and on occasion, in bordering Latvia) that is the land known in Litvak culture as Zámet (a Jewish person therefrom is a Zámeter, f. Zámeterin or deep Litvak Zámeterke).

In broad terms, it corresponds to historic Samogitia (Lithuanian Žemaitija). However, the specific cultural and linguistic borders relevant to Litvak culture and Yiddish dialectology often make for a unique Litvak geocultural configuration. For a general Yiddish orientation on the (pre-Holocaust) linguistic situation, see e.g. the maps for ‘ear’ and ‘dove’ vs ‘deaf’ in the in-progress Language Atlas of Lithuanian Yiddish.

The Fate of an Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery that is Part of Now

O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

This comment first appeared in The Times of Israel on 22 May 2013.

One of the predictable consequences of genocide is the spectacle of old cemeteries without relatives or descendants of the buried to care for the gravestones or the site. Some stones will fall, some will sink, and then some will just be taken as usable components for the foundations of houses, the ballast of roads or the walls of a basketball court.

An Unmarked Holocaust Mass Murder Site in Riga, the Latvian Capital

INTERVIEW WITH RIGA HISTORIAN MEYER MELLER (MELERS)

by Aleksandrs Feigmanis

The great Russian author Lev Tolstoy wrote in his story “From the Notebook of Prince D. Nekhlyudov. Luzern.”

“Seventh July 1857 in Luzern in front of the Schweizerhof Hotel, where most rich people would stay the itinerant beggar-singer sings songs for half an hour and plays his guitar. About a hundred people heard him. Three times the singer asked the crowd to give him some money or food. Nobody gave him anything and many laughed at him.” […] This is the event which the historian of our times should write about with fiery irascible letters. This event is much more important and serious and has much more sense than the facts written in newspapers and history books. […] This is not a fact for the history of human acts, but for the history of progress and civilization.”

All that marks this major Holocaust mass grave in Riga, the Latvian capital, is a plastic bucket of flowers near the empty frame of a long-destroyed Soviet-era tin sign.

If you wish to see the mass grave take number 13 bus from the central station headed for Plavnieki and get off at the stop called Darzenu baze (roughly a half-hour ride). When you get off, turn from Lubanas street to the right until you come to Darzenu baze (“warehouse for vegetables”). In the pine woods some 300 meters from the warehouse you will see a little hill, without any mark, inscription or tombstone. Just a few primitive buckets of plastic flowers mark the site. They are placed near a wood frame stand that once, in Soviet times, held within it a bilingual tin sign about the site, that has long been destroyed and removed. The site is about 600 meters from the nine-floor apartment houses in Riga’s Plavnieki district.

On the Preservation of Lithuania’s Old Jewish Cemeteries

O P I N I O N

by Joseph Levinson

Joseph Levinson (Josifas Levinsonas) in Vilnius, 2013. Courtesy of the Levinson family.

On April 25th 2013 an event dedicated to the recording, maintenance and preservation of old Jewish cemeteries in Lithuania was held at the Vilnius premises of the Lithuanian Jewish Community. It was organized by the NGO “Maceva” and chaired by one of the NGO’s founders and leading figures, himself a resident of Brussels.

The April 25th evening in Vilnius went “smoothly” until a veteran member of the Jewish Community politely pointed out that much of the work that the NGO was taking credit for and presented as a miracle dropped from the heavens had in fact been carried out many years earlier by the very Jewish Community in whose premises the event was held. There was a moment of shock when the event’s chairman reacted by saying “There are different kinds of Jews!” instead of thanking the senior member of our community for his well-intentioned, polite and factual corrective remarks from the floor.

Trilingual Memorial Plaque Unveiled on Zhager Town Square

O N – S I T E R E P O R T / O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

ZHAGER, northern Lithuania. Over a hundred people gathered here today on the historic town square to unveil a trilingual plaque memorializing the erstwhile Jewish population of thousands in the town, today Žagarė. The event was incorporated into the annual Cherry Festival and suitably entitled “You can’t fudge the history.”

SEE ALSO THE REPORTS BY ROD FREEDMAN AND SARA MANOBLA

THE QUESTION: IS IT THE ONLY TOWN-CENTER IN ALL THE LAND WITH CLEAR AND TRUE WORDS ON THE TRUE FATE OF THE JEWISH POPULATION?

The text — in English, Lithuanian and Yiddish — summarizes the unvarnished history, with prominent reference to local Lithuanian collaboration (though historians will quibble with the use of “some” in place of “many” among other points). It is placed right in the center of town, rather than at a mass grave site deep in the forest; that might well be a first in modern Lithuanian history.