by Dovid Katz

Rúmshishok (informally: Rúmseshik), some twelve miles from Kaunas (Kovno), was a beloved Lithuanian shtetl where Lithuanians, Jews and others lived together for many centuries in peace (the town goes back to the fourteenth century). The massacre of the town’s Jews during the Holocaust was close to complete (outlines of the history here and here). According to the new Lithuanian Holocaust Atlas, the perpetrators were comprised of “white armbanders” from the town plus “Lithuanian self-defense unit troops” from Kaunas.

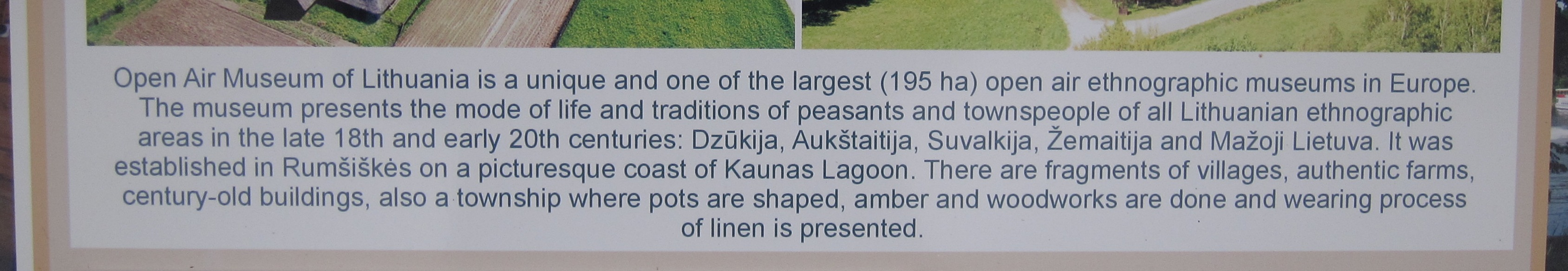

Now Rumšiškės in modern Lithuania, the town is internationally known for its neighboring extensive open air museum of the Lithuanian provinces, including town, hamlet and rural settings, all meticulously reconstructed.

The famous open air museum was established in Soviet times in 1966 and fully opened in 1974. It claims to be one of the largest such ethnographic museums in Europe. Its official name is Lietuvos liaudies buities muziejus which can be translated Lithuanian Folk Life Museum. Its own English signs call it the “Open Air Museum” and it has also been known as the Museum of Rumšiškės.

A prominent Jewish-interest guide and historian — we will call him “Shleyme” — told DefendingHistory.com that there “is nevertheless something wrong” with the museum’s attitude toward the Jewish component of Rumšiškės, the old town it so meticulously reconstructs with full scale houses and open spaces. The actual old town, incidentally, was destroyed in a flood, adding to the historic gravitas of the nearby reconstruction on the grounds of the open air museum. And the guide, by the way, is the same one Dan Jacobson called “Shlomo” in his Heshel’s Kingdom (1999).

On a brisk mid-winter Sunday morning, he led our team into the sprawling and impressive site.

A multilingual welcoming sign sets out the parameters. The English reading eye zooms in to the English text.

♦

At this point, we asked our guide:

“So what’s wrong?” He replied:

“Two things. First, no mention that the town actually reconstructed, Rumšiškės, itself had a prominent Jewish minority situated at its very center, and no mention that one of the mass graves where ‘Lithuanian patriots of 1941’ murdered many of the town’s Jews was situated right here, deep inside the open air museum’s territory.”

There was a long silence, as we all follow our guide deeper into the historical park.

Some distance inside the main gates, there is large map of the open air museum.

The map of the famous open air museum includes all the reconstructions built on its grounds, but no mention of its one actual historic site: the mass grave of a part of the Jewish population of the shtetl whose reconstruction lies at museum’s very heart.

There is no mention on the map of the location of the Holocaust mass grave site on the grounds. Shleyme, elegantly equipping himself with a pointer shaped fallen branch, shows us the spot.

Our guide shows us the spot using a fallen branch.

During Soviet times, the state totalitarian atheist ideology dictated that the museum’s reconstructed shtetl was to omit houses of worship of all faiths, a shocking example of history politicized beyond the pale: this was after all for 1960s Soviet authorities a reconstruction of a town of the past, not some model for the future.

But what has happened, according to our guide, in free and independent Lithuania over the last two decades, is a “partial corrective that is in its own way also shocking”. Shleyme explains that once the Soviet Union fell, authorities soon found the political will and financial resources to rectify some of the Soviet distortion of the town’s history. There was a full scale reconstruction of the church of Rumšiškės, but not of its synagogue or other Jewish addresses! Christianity was recovered for the region’s most impressive full scale reconstruction of an old town. The place’s Jewish history was “just left out”. Moreover, the “omitted synagogue” had been used in August 1941 to incarcerate, humiliate and torture part of the town’s Jewish population prior to being murdered, in some cases at the designated mass grave site now within the open air museum (1922 image of the synagogue on JewishGen).

There is just the church and the town square with its “Jewish looking” houses on all three sides facing the church.

But where is the synagogue?

According to Shleyme, a number of the houses on the town square have that “classic Jewish town square look” about them, and with a minimum of effort in local and national archives, it would be easy to produce the list of inhabitants of each for both late czarist Russia (when Rumshishki, as it was known in Russian, was in the Kovno province of the Russian Empire) and interwar independent Lithuania (when Rumšiškės was in the Kaunas district of independent Lithuania).

Our guide says: “A very Jewish looking house, but of course the sign for the family’s shop on the ground floor (‘Tinsmith’s Workshop’) is in Lithuanian only. Before World War I there would have been Russian for sure, and between the wars Lithuanian plus Yiddish was very typical except where banned by law.”

Shleyme goes on to explain in a sad voice:

“But there is no such effort because the authorities who run these museums don’t want to include the country’s Jewish history where they can avoid it, especially where a museum attracts many domestic and regional and ‘general international’ visitors and is not one of the big-city things put on to show the diplomats and the foreign Jews when they come to Vilnius.”

We ask if there is any mention of the Jewish population centered in the town center? He says there is not on site, other than an oblique and disturbing misspelling of the word for ‘shop’ in one of them, meant to make fun of the Jewish accented pronunciation of the word as opposed to its standard Lithuanian form (a misspelling on a shop sign was not however typical — these were always checked with a local expert; this was just an opportunity, according to our guide, to make fun of the unmentionable element of the town’s history). On the open air museum’s website, there is a Lithuanian language page about the shops with this one mention: “So many enticing little shops where the shoppekeepers (mostly Jews) pull you inside by the sleeve” …

♦

We then come to the question of the mass grave of part of the Jewish population of Rúmseshik that is on a site that ended up deep inside the open air Lithuanian Folk Museum built in the Soviet period. We knew from earlier on that it is not mentioned on the sign in front, on the website or on the large map that greets visitors.

But how is the mass grave marked? Shleyme answers:

“In the early 1990s, foreign Jews who hail from the town made a small stone gravestone style monument on the site of the mass grave, and now the letters are already rubbed out from the weather and impossible to read. However, after years of my own lobbying, a standard museum grade sign in Lithuanian was put up at the point on one of the roads that is nearest to the grave marker. Just one problem. Instead of ‘Mass Murder Site of Jews from Rumšiškės’, as I had suggested based on the normal signposting of mass grave sites, the sign reads ‘Holocaust Memorial’ as if it’s some general abstract unannounced memorial in the middle of the woods. And the Lithuanian or foreign visitor will not learn much about what happened, and who the murderers were, even if he or she is motivated to check out this particular forest path.’

‘Holocaust Memorial’, reads the sign, instead of: Mass grave of part of the Jewish population of Rumšiškės.

The stone’s inscription has become illegible, in marked contrast to the caring upkeep evident from all other markers and signs in the open air museum.

An image of the stone from earlier years is available on JewishGen, where the Yiddish is seen to read: ‘At this site in 1941 the Hitlerist murderers and their local helpers in 1941 murdered Jewish people: men, women and children’. The Lithuanian text has the same information but uses the phrase ‘the Nazis and their collaborators’ instead of ‘the Hitlerist murderers and their local helpers’.

According to the Lithuanian Holocaust Atlas, the murder here of about eighty Jews was organized by the local white armbanders but carried out by soldiers from the “Lithuanian Self-Defense Unit troops” who came from Kaunas to do their day’s work, on 27 August 1941. According to Yahadut Lita “ninety women and children” were murdered here (vol 4, Tel Aviv 1984, pp. 358-369, JewGen English translation here).

In 2011, many events were carried out by the Lithuanian government to honor the “rebel heroes” of 1941, to the consternation of Holocaust survivors and scholars internationally.

♦

The open air museum’s attitude toward the town’s (and the country’s) Jewish heritage is in marked contrast to an intricate indoor miniature model of old Rumšiškės made by Vytautas Markevičius, which meticulously includes the town’s Jewish sites and addresses in a spirit of historical accuracy and multicultural inclusiveness. That model is housed in the town’s Jonas Aistis Museum.

Rúmshishok had its share of shtetl Jews who went on to fame and various accomplishments in the wider Jewish world. Among its children who became part of Litvak lore are Reb Léybele Rúmshishker (Judah Leib Katz) who was one of the Vilna rabbinical court judges who adjudicated a major trial of a Hasidic dissident in 1798, at the height of the misnagdic-hasidic conflict. Reb Chaim Elchonon Tsadikov, born in 1813, who also moved on to Vilna became one of the city’s most famous magídim (Jewish religious lecturers). Jacob Katz, who was born in 1863, became the head of Hirshl’s Yeshiva in Slabódke (Vilijampolė), Kovno (Kaunas).

Further reading:

-

Berl Kagan’s Yídishe shtet, shtétlakh un dórfishe yishúvim in Líte (Jewish Cities, Towns and Villages in Lithuania [in Yiddish], New York 1991, pp. 549-551);

-

Dov Levin’s Pinkás Hekehillót (Encyclopedia of Jewish Communities — Lithuania [in Hebrew), Jerusalem 1996, pp. 633-635).

-

Yahadút Líta, vol. 4: HaShoah, 1941-1945, Tel Aviv 1984, pp. 358-359.

-

The JewishGen page on the town with many fascinating links and references.

-

Rolandas Gustaitis, Jews of the Kaišiodoris Region of Lithuania, Bergenfield 2010.

-

Olga Zabludoff’s essay.