O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

Photos by Richard Schofield (© R. Schofield)

The Lazdynai Middle School in Vilnius, built in the early 1970s, has an admirable reputation, inter alia for an excellent trilingual policy enabling Polish and Russian to flourish alongside the national language, Lithuanian, in a spirit of multicultural respect and harmony so fitting for the city’s history.

Updates to May 2013:

Return visit to the Stones of Lazdynai

♦

Updates to 15 December 2011

Samuel Gruber’s Jewish Art and Monuments

Facebook discussion thread

Work in Progress: A Cultural Dictionary of Lithuanian Jewish Gravestones

Perhaps that makes it all the more curious that after some forty years, twenty of them in freedom, the outside retaining walls dividing terraced lawns, walkways and most prominently, a basketball court, continue to be made entirely of the plundered Jewish gravestones from the old Zarétsher bes-éylem, as the Jewish cemetery of Užupis (Yiddish Zarétshe) was known in the Litvak Yiddish of Vilna (Yiddish: Vílne). Also known as the New Jewish Cemetery (it dates from around 1831), it figures prominently in such classic works of Lithuanian Yiddish literature as Chaim Grade’s classic Di Agúne and Daniel Charney’s memoir A Litvak in Poland.

Numerous stones have perfectly visible Jewish lettering, symbols and designs.

The school grounds’ outside walls comprised of the pilfered Jewish gravestones have nothing to do with the structure of the school’s building and removing the stones and finding a culturally respectful home for them would not touch with one hair the school building or any other.

Moreover, the walls made from the stones extend well beyond the school’s grounds to surrounding parts of Lazdynai, where a large supply of Jewish gravestones were brought from the cemetery site after the city’s Soviet-era administration destroyed the cemetery.

For this school’s and the city’s educators, there is a magnificent opportunity for an inspiring project, in partnership with the remnant living Jewish community of course, for volunteer pupils under professional supervision to ‘deconstruct’ these walls and to digitize, order and analyze the remnants of one of the fabled cultures of Vilnius that has been calling out to them all these years through the letters on stones.

There is an even more inspiring project on the cards: A team of pupils over a period of time can put the gravestones, as far as possible, together again, thus giving the once-upon-a-time Vilna residents they commemorate their names and sign-for-eternity back again.

This is an opportunity that would be the envy of a many a middle school on this planet.

Verily in the spirit of Ezekiel 37.

◊

In the image below, the white stone with the fragmentary circular top arch is for a cohen, a descendant of the priestly caste of Aaron, brother of Moses. Ancient Jewish tradition and modern DNA testing alike ascertain ‘the cohen line’ and it is frequently designated by such Jewish surnames as Cohen (Kohen, Kogan, Kagan, Kaganovitch, etc), Kahana (Cahana, Cahane, etc.) and Katz, among others. A cohen’s gravestone traditionally contains two hands with the fingers distributed (separate thumb, then 2+2 with maximal spacing between the three blocs on each hand) as per the ancient tradition for the position taken by the cohen when performing the priestly blessing. In the study of Jewish gravestones, the icon is known simply as cohen hands.

The ancient cohanic blessing (see Numbers 6: 22-27, actual blessing: verses 24-26), with the cohen’s hands in the configuration illustrated on this stone, continues to be performed in the synagogue on designated holidays, including of course, both functioning prayerhouses in Vilnius today. Worshippers would be delighted to welcome faculty and students from Lazdynai Middle School who might wish to acquaint themselves with this tradition whose letters cast in stone have been trying to speak to them for some decades. Of course the Jewish Community of Lithuania always welcomes pupils interested in learning more about one of old Vilna’s famous cultures that was nearly made extinct during the Holocaust.

◊

The first three letters of the word for ‘died’ (preceding the Jewish calendar date on traditional Jewish gravestones) can be discerned on the stone below. In the following line the general calendar year [19]29 is visible. Letters can be straightened by moving some 90 degrees counter-clockwise.

◊

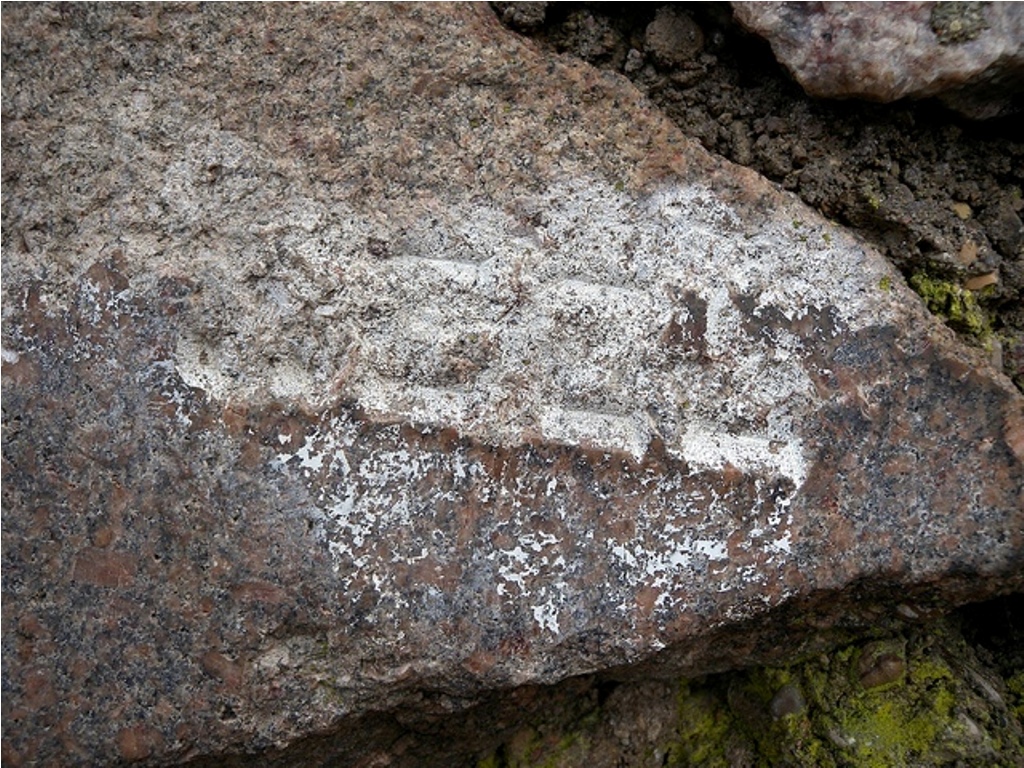

The stone fragment below can be straightened by moving some 90 degrees counter-clockwise. The first line contains a clear alef and a possible lamed, which might make for the beginning of the name Eylióhu (Elijah). The next visible start of the line may contain the abbreviation used for a living person (a blessing translating roughly ‘may his maker and redeemer guard him’), presumably the father of Elijah who was still alive when his son died. The following line may start with the word ‘from the family of’ presumably preceding the name of an illustrious ancestor.

◊

The stone below was for a respected rabbi. The visible three letters of the third line (moved 90 degrees to the left) are part of the abbreviation for ‘Our teacher the rabbi […]’.

◊

The readable line below (turned upside down) is the end-of-gravestone acronym for the words ‘May his/her soul be bound in the bond of (eternal) life’. The first three of the five letters are fully preserved, along with a part of the fourth.

◊

Turned 180 degrees, three letters on the stone below, only one of which is totally clear, may be part of the year 5699 (= 1938-1939). Further elucidation is possible by various chalk and stencil work with the actual stones.

◊

The fragment below is from a woman’s gravestone, and the middle line starts: ‘daughter of Reb’ […]. Reb is the Yiddish (and Ashkenazic) honorific title for an adult male and precedes his given name. The second line seems to start with the word for ‘fell’ and may be from Lamentations 2:21, a biblical line — ‘My virgins and my young men are fallen by the sword’ — used to preface stone texts for a young man or woman who met a violent death. Moved around 90 degrees clockwise the letters are upright. The first word of the last line is the start of a phrase that translates in the infinitive ‘to breathe one’s last’ and is one of the various ways of saying ‘died’ on traditional Jewish gravestones.

◊

All that can be made out on the middle stone below, straightened by a leftward 90 degree shift, is the lonely, solitary letter tof (pronounced [t] or [s] depending on position in the word).