O P I N I O N

History

Distorted Nationalist History in Ukraine

Footprints of Adolfas Ramanauskas-Vanagas in the Mass Murder of the Jews of Druskininkai

O P I N I O N

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

Adolfas Ramanauskas Vanagas was a well-known post-war partisan commander. Here’s what the Center for the Study of the Genocide of the Residents of Lithuania has to say about him on their website:

Studies on Nazi Collaboration in Ukraine and Current Attempts to Glorify the Collaborators

Recent Publications by Dr. Grzegorz Rossoliński-Liebe (Berlin):

2011: “The Act of 30 June 1941, and its 2011 Commemoration in Ukraine” in Defending History, 25 June 2011.

Exhibit Honoring Jewish World War II Veterans Disappears Into Vilnius Thin Air

O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

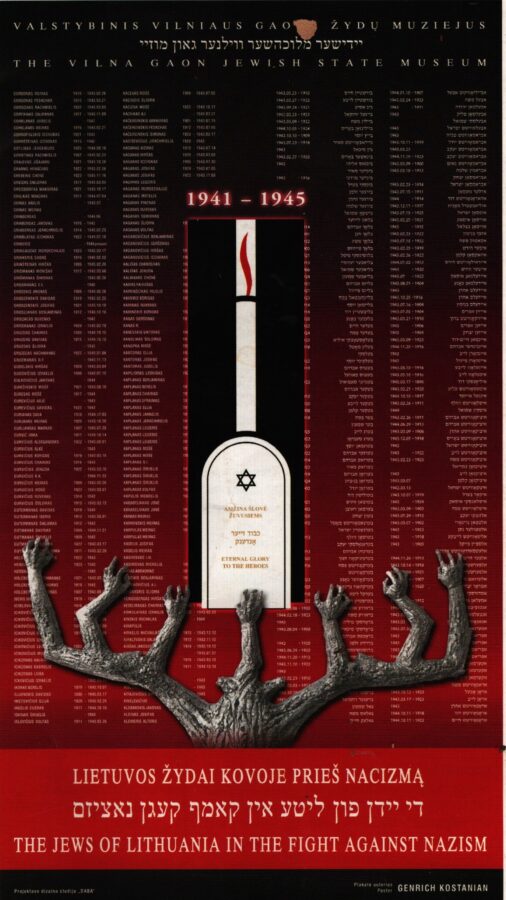

VILNIUS—Three Vilnius-based members of the Defending History team visited the Pylimo Street section of the Vilna Gaon Jewish State Museum of Lithuania this week, and asked to be shown the famous and widely admired exhibit honoring the Jewish veterans of the war against Hitler in Lithuania. The exhibit, titled Lithuania’s Jews in the Struggle Against Nazism, was opened in a spirit of unity, reconciliation and mutual respect, some fourteen years ago (PDF of the report in the Spring 2000 English edition of the Jewish community’s then quadrilingual newspaper, Jerusalem of Lithuania, which was edited by Milan Chersonski from 1999 until 2011; JPEG; reduced image below). Its primary creators are Joseph Levinson and Rachel Kostanian.

Sergijus Staniškis Litas: Who’s Hiding the 1941 Gaps in His Biography — and Why?

O P I N I O N / P O L I T I C S O F M E M O R Y / C O L L A B O R A T O R S G L O R I F I E D

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

Authorized translation from the Lithuanian original by Geoff Vasil.

Today Sergijus Staniškis Litas is presented as a noble partisan commander who concentrated his unusual skills on battling the occupiers. At least that’s how the writers of the Lithuanian Center for the Study of Genocide and Resistance present him on their webpage at http://www.genocid.lt/datos/stanisk.htm.

Artists Knew, Allied Leaders Kept Silent

O P I N I O N

by Roland Binet (Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium)

When I was in New York last year, I saw an extraordinary exhibition of paintings by Marc Chagall, “War, Exile and Love” at the Jewish Museum. The focus was on the works he produced during his years of exile in the United States. This exhibition, well attended, shed an interesting light on what the artist knew about the horrific events unfolding in Europe at the time of his sojourn in the United States.

New “National Council of Historical Memory” to Control Thought About History in Lithuania?

VILNIUS—Among other news portals in Lithuania, 15min.lt reported on 23 December that a group of nationalists in the Seimas (parliament) had proposed establishment of a new institution, the “National Council of Historical Memory” to set the “indisputable truth about historic events.” Coming on top of the 2010 red-brown criminalization of opinion law that has brought alarm from human rights circles in the European Union, this latest layer of state establishment of alleged historic truth would compound the damage.

Vilnius Genocide Center Releases a New Graywash on the Vilna Ghetto

B O O K S / O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

◊

The unfortunate and wasteful campaign of Holocaust obfuscation waged by certain East European state institutions continues apace. The level of investment continues to strike outsiders as puzzling, given current economic and cultural issues and the younger population’s clear focus on the future and a better life for all in the new and multicultural European Union. Here in Lithuania, the first victims of the government’s (rather Soviet-style) “genocide industry” are the hard-working people of the country who deserve more judicious disbursement of their nation’s resources. The state-sponsored Genocide Center has just released three simultaneous editions (English, Lithuanian and Russian) of a new book on the Vilna Ghetto by historian Arūnas Bubnys, its own “director of the Genocide and Resistance Research Department.”

The unfortunate and wasteful campaign of Holocaust obfuscation waged by certain East European state institutions continues apace. The level of investment continues to strike outsiders as puzzling, given current economic and cultural issues and the younger population’s clear focus on the future and a better life for all in the new and multicultural European Union. Here in Lithuania, the first victims of the government’s (rather Soviet-style) “genocide industry” are the hard-working people of the country who deserve more judicious disbursement of their nation’s resources. The state-sponsored Genocide Center has just released three simultaneous editions (English, Lithuanian and Russian) of a new book on the Vilna Ghetto by historian Arūnas Bubnys, its own “director of the Genocide and Resistance Research Department.”

Dr. Bubnys is also a member of the state-sponsored “International Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania” (known for short as the “red-brown commission”). He was one of a minority of members of the Commission who refused to sign the (in the opinion of some, inadequate) letter of 14 October 2013 to Dr. Yitzhak Arad.

How Has Post-Soviet Lithuania Used Holocaust Remembrance to Project a “New” European Identity?

O P I N I O N

by Rachel Croucher (Melbourne, Australia)

Lithuania declared its restoration of independence from the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) on March 11, 1990. The country then began to immediately seek closer ties with established Western European institutions as a means to consolidate its national and economic security. After centuries of subjugation at the hands of various foreign powers, this need for national and economic security was seen as being of primary and urgent concern to the fledgling democracy. This race to join as many Western European institutions as possible was also a way to prove to the rest of the world that Lithuania was now in practice a true European country, part of the post-1945 Western European order. The sentiment behind this is best expressed by Czech-born and naturalized French writer Milan Kundera when he stated in 1989 that

If Israel Can Honor the USSR’s Unquestionable Role in Bringing Down Hitler, Why Can’t France and the European Union?

O P I N I O N

by Didier Bertin

From the very beginning, the source of our problems is to be found in an inaccurate narrative of World War II that is rather widespread here in France. This can be explained in part by France’s position as a de facto ally of the Axis at first, starting from the time of Petain’s surrender to Hitler’s forces in 1940. It was rather late in the war that a substantial segment of society in the country per se (as opposed to the heroic resisters who had joined the Allies outside surrendered France’s borders) became a stalwart ally of the United States and Great Britain, at a time when that was by a confluence of circumstances most convenient for all three countries.

Efraim Zuroff Critiques Vilnius Genocide Center’s Latest Attempt to Massage Figures (and Ethics) of Local Holocaust Perpetrators

In a statement issued in Jerusalem today, the Simon Wiesenthal Center’s Israel director Dr. Efraim Zuroff noted two major flaws in a recent report issued by the state-sponsored Genocide Center in Vilnius, Lithuania. The report’s key findings, presented by the Center’s Dr. Alfredas Rukšėnas, were published by the Lithuanian news portal Delfi on 25 October 2013 (English translation available in Defending History).

According to Dr. Zuroff:

“The findings of the report, as presented by the coordinator of this project, are clearly part of a systematic attempt by the Lithuanian government to minimize the role of ethnic Lithuanians in the mass murder of Jews during the Holocaust. Based on the records in our archives, I can unequivocally state, that the figure of 2,055 Lithuanians whose direct and indirect participation in Holocaust crimes was confirmed by this study, is a gross underestimate of the number of Lithuanians complicit in Shoah crimes, designed to deflect blame from local collaborators and hide the extensive scope of Lithuanian involvement in the mass murder of Jews, both in Lithuania and outside her borders.

“Also highly objectionable is the assertion by Dr. Rukšėnas that those Lithuanians who indeed murdered Jews really had no choice but to do so, having received orders to commit murder from their superiors. Besides the fact that in many cases, these superiors were themselves Lithuanians, such arguments have been consistently and unequivocally rejected by courts all over the world, starting with the Nuremberg Trials.”

Genocide Center in Vilnius Responds to the List of Alleged Holocaust Perpetrators Published by the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel

Editor’s note: The following is an English translation by Geoff Vasil of an article that appeared on Delfi.lt on October 25, 2013. The images that appeared with the original Lithuanian text are not reproduced here.

In 1999, The Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel published Crime and Punishment, compiled after many years of work, by its chairman, Tel Aviv attorney Joseph Melamed, a native of Kovno (Kaunas), Holocaust survivor and veteran of the Jewish partisan resistance in Lithuania and of the Israeli War of Independence. In the late 1990s, Mr. Melamed wrote repeatedly to Lithuanian prosecutors, explaining that some Holocaust perpetrators and witnesses were still alive and investigations could be pursued.

Questions and Answers on the Holocaust-Gulag “Competitive Martyrology”

O P I N I O N

by Michael Shafir (Cluj-Napoca, Romania)

1. Approximately when did the drive to equate the Holocaust and the sufferings endured by people under Communist regimes start?

It is very difficult to pinpoint an exact date. In the West, a number of Sovietologists have long driven attention to the fact that the horrible crimes perpetuated by Stalin and his henchmen in East Central Europe deserved the attention and the opprobrium that Nazism met with after the Second World War. Due to Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s famous book Gulag, these crimes soon began to be referred to under the synthetic name of that book. The collapse of the Communist regimes in the region in 1989 and the implosion of the Soviet Union in 1991 intensified that drive, which also found an impulse in the once popular (but later criticized) “totalitarian model.” That model was now revived, finding support particularly in the eastern part of Europe that had suffered under Soviet domination. Western historians were (and still are) quite divided over this issue. For example, Robert Conquest, who produced several important books on Stalinist crimes, was reluctant to place the Holocaust and the Gulag on the same footing. On the other hand, Stéphane Courtois, who edited and contributed to the Black Book of Communism, not only embraced the comparison, but insisted on

Yehiel Zilberman’s Memoirs (excerpt)

M E M O I R S

by Yehiel Zilberman

Translated from Russian by Olga Gorelik

This is a chapter from the memoirs written by Yehiel Zilberman, translated from Russian by Olga Gorelik (© Yehiel Zilberman & Olga Gorelik). The chapter appears in Defending History by permission of the copyright holders, with thanks to the good offices of Victor Shifrin (Los Angeles).

Yehiel (Yekhíel) Zilberman was born in Lithuania in 1922. In 1940 he graduated from the H. N. Bialik Hebrew High School in Shavl (Šiauliai) and was admitted to the Institute of Commerce in the same city. In June of 1941, one year after Lithuania fell under Soviet rule, Yehiel along with his parents and brother Moshe (Mikhail) was exiled to the Altai Region in Russia where he lived until 1945. In 1949 he graduated with Honors from Gorky Industrial Institute and became a chemical engineer. Yehiel worked in both manufacturing and scientific research. In 1954 he received his PhD from the Moscow Institute of Chemical Technology. In 1965 Dr. Zilberman received the title of Professor. From 1970 to 1990 he taught at Gorky Polytechnic Institute.

Yehiel (Yekhíel) Zilberman was born in Lithuania in 1922. In 1940 he graduated from the H. N. Bialik Hebrew High School in Shavl (Šiauliai) and was admitted to the Institute of Commerce in the same city. In June of 1941, one year after Lithuania fell under Soviet rule, Yehiel along with his parents and brother Moshe (Mikhail) was exiled to the Altai Region in Russia where he lived until 1945. In 1949 he graduated with Honors from Gorky Industrial Institute and became a chemical engineer. Yehiel worked in both manufacturing and scientific research. In 1954 he received his PhD from the Moscow Institute of Chemical Technology. In 1965 Dr. Zilberman received the title of Professor. From 1970 to 1990 he taught at Gorky Polytechnic Institute.

Dr. Yehiel Zilberman has been resident in Haifa, Israel, since 1990.

English Translation of the Lithuanian Text on the Vilna Ghetto Provided by the Office of the Chief Archivist of Lithuania…

The following is an English translation, by Geoff Vasil, from the original Lithuanian text that appears on the website of the Office of the Chief Archivist of Lithuania concerning the Vilna Ghetto, on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of its liquidation on September 23, 1943.

In an important article that appeared in Lithuanian in Bernardinai.lt, and in English in the Lithuania Tribune, author Sergejus Kanovičius pointed out the remarkable disparity of tone between the Lithuanian version on the Chief Archivist’s website (that appears below in English translation), and the English version provided on the Chief Archivist’s website…

Inclusion and Occlusion

O P I N I O N

A REVIEW OF THE PRAGUE PLATFORM’S TRAVELLING EXHIBITION “TOTALITARIANISM IN EUROPE” PAID FOR BY THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION (CURRENTLY ON SHOW AT TUSKULĖNAI PARK IN VILNIUS, LITHUANIA)

by Geoff Vasil

At the edge of downtown Vilnius, along the river Neris where the buildings suddenly turn old and worn and bushes, trees and grass take on unmanicured forms, across the bridge whose entree is gated by the Danish and British embassies to Lithuania, there is a strange park nestled in between some very empty Soviet-looking and much older buildings.

Chersonski Replies to Aleksandravičius on the 2012 Kaunas Reburial with Full Honors of 1941 Nazi Puppet Prime Minister

Who’s Afraid of Defending History Dot Com?

O P I N I O N

by Dovid Katz

It is gratifying that numerous scholars from different parts of the world, and indeed of differing opinions on the contentious issues that lie at the heart of Defending History, have on occasion found it a useful resource for data and views on various topics, including the Double Genocide movement, the Prague Declaration (2008), the Seventy Years Declaration (2012), the politics of memory, Holocaust Obfuscation, glorification of Holocaust perpetrators (and attempted criminalization of resistance heroes), East European antisemitism, racism, homophobia, and Litvak identity theft (more on contents and quick intro page).

Free Speech and Holocaust Remembrance in the Eastern European Union

O P I N I O N

by Geoff Vasil

NOTE: This was written in response to “Foreign countries use far-right operations to undermine Lithuania’s image” published on June 7, 2013, on the Lithuania Tribune website.

Initially the editor-in-chief of the Lithuania Tribune agreed to publish the following reply in the Lithuania Tribune, but then changed his mind and finally refused, only informing the author a month later…