O P I N I O N

by Milan Chersonski

Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij) was for a dozen years (1999-2011) editor-in-chief of Jerusalem of Lithuania, the official quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. He was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania. The views he expresses in Defending History are his own. Photo: Milan Chersonski (image © Jurgita Kunigiškytė). Milan Chersonski section.

Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij) was for a dozen years (1999-2011) editor-in-chief of Jerusalem of Lithuania, the official quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. He was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania. The views he expresses in Defending History are his own. Photo: Milan Chersonski (image © Jurgita Kunigiškytė). Milan Chersonski section.

Real Heroes and Supposed Heroes

Who Protested and Why?

In May 2012 solemn funeral events were held in Kaunas: the ashes of the interim prime minister of the Provisional Government of Lithuania (hereinafter PG) Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis were transferred from the state of Connecticut in the United States, where he was buried in 1974, to Kaunas, the former temporary capital of Lithuania. There the ashes were reburied.

The day after the reburial the country’s largest newspaper, Lietuvos rytas, published an interview with Professor Egidijus Aleksandravičius conducted by journalist Valdas Bartusavičius (English translation). The subject of the interview was the reburial of Ambrazevičius’s ashes with state honors, about which almost all the media of the country were writing daily.

“This wasn’t the academic community but a decision of the VMU administration which became frightened that they were going to get hit over the head with a club by the Jews.”

— Professor Egidijus Aleksandravičius

Though it may seem strange, Aleksandravičius’s interview passed almost unnoticed, but considering he is a prominent scholar and historian, professor, author of numerous academic publications, director of the Institute of Emigration, known in his homeland and abroad, and on the published program of the September 2013 Fourth World Litvak Congress dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the destruction of the Vilna Ghetto, it makes sense to return to the subject of that interview which remains current as ever.

Before starting the interview, Bartusavičius provides an introduction, in which, foregoing the interviewee’s opinion, he shares with the readers his own thoughts:

“The ceremony for the reburial of Brazaitis gave rise to protests by Jews who judge negatively the activities of the Provisional Government of 1941, which published antisemitic statements. This led to the decision by Vytautas Magnus University not to allow a conference on Brazaitis which had been planned there.”

Which Jews were “annoyed” so much that they protested? How can modern Jews have any connection with the reburial of a man who died almost forty years ago? There is no answer.

After complaining to the readers about the Jews, who are often used as a convenient target in the Lithuanian media, the Lietuvos rytas correspondent asks Professor Aleksandravičius:

“Are the Jews justified in being angered by the idea of honoring Brazaitis by reburying his remains in his homeland?”

The question itself called for a simple and clear answer: “Yes, they are,” or “No, they are not.” Aleksandravičius did not find it necessary to clarify the question, although he knew that the protest against the state’s participation in the reburial of Ambrazevičius was expressed not by “the Jews,” that is, a gray mass of phantoms, but by a particular person, whom, by the way, Aleksandravičius has known well and for a long time: chairman of the Jewish Community of Lithuania Simon Alperovich (Simonas Alperavičius), who headed the community for twenty years, until mid 2013. He was elected head of the community by Lithuanian Jews six times and is now the community’s honorary chairman. His direct responsibilities include protecting the interests of the community and each of its members. Therefore, it would be more ethical to talk not about “the Jews” in general, but about the head of the organized and officially acting community, the Jewish Community of Lithuania, restored in our country thanks to the restoration of Lithuanian independence, and about a specific person, Dr. Simon Alperovich. (There were of course other protests too, both domestic and international.)

Alperovich protested not against the fact of the reburial, but against granting the reburial official status. As a citizen of this country and as the head of his organization, he has the right to express not just his own opinion, but the opinion of the community as well. From the point of view of the Jewish community and its chairman, Ambrazevičius has no moral right to be honored and commemorated by the Lithuanian state, because some of his 1941 government’s decisions were antisemitic and helped implement the “final solution of the Jewish question,” that is, the complete annihilation of the Jews as a people.

The most shocking part of the interview comes near the end. Instead of being relieved that his beloved Vytautas Magnus University (VMU) in Kaunas was spared the international shame of an event honoring a major Nazi collaborator in this part of the world, the professor is bitter that it was cancelled! Bitter that “the Jews” somehow prevented such a glorious event from gracing his university and that “they” wielded some mystic power over his university’s administrators.

“This wasn’t the academic community but a decision of the VMU administration which became frightened that they were going to get hit over the head with a club by the Jews.”

Turning now to the finer points of the exchange, Bartusavičius’s allegation that Jews judge the Provisional Government negatively because it made “antisemitic statements” misrepresents the facts: every document adopted by the Provisional Government is not just a “statement,” but a regulation, a resolution, i.e., a binding document of distinct importance. The Provisional Government adopted seven major and many lesser resolutions whose purpose was to implement the Nazi genocide of the Jewish people in Lithuania. (See Lietuvos laikinoji vyriausybė: posėdžių protokolai. 1941 m. birželio 24 d. – rugpjūčio 4 d. Vilnius, 2001 . Parengė dr. Arvydas Anušauskas; [Protocols of the Sessions of the Provisional Government of Lithuania, June 24 – August 4, 1941.Vilnius, 2001. Prepared by Dr. Arvydas Anušauskas]).

◊

Provisional Government’s Records Give Testimony

There is no doubt that both interlocutors are familiar with the Provisional Government’s protocols. According to the documents, the activities of the PG in respect to the so-called “Jewish question” are not as innocent as made-to-order “experts” may seek to represent. They claim that the establishment of the PG was an attempt to restore the independence of Lithuania. The genocide of a people or any section of a people because of their nationality is incompatible with the restoration of independence.

From the protocols of the Provisional Government of Lithuania:

Pages 17-18, Protocol #5, June 27, 1941:

“Minister Žemkalnis reported unusual atrocities committed against Jews at the Lietūkis Garage in Kaunas.

Resolved: Despite all the measures that should be taken against the Jews for their Communist activities and the damage they are inflicting upon the German military, partisans and individual citizens should avoid public executions of Jews. It has been found out that those acts were committed by people who have nothing to do with the staff of the activists, partisans’ headquarters, or the Provisional Government of Lithuania.”

The resolution does not prohibit killing Jews, it only recommends that public executions of Jews be avoided. About 240,000 Jews lived in pre-war Lithuania. According to the absurd belief of Ambrazevičius’s Government, they all were engaged in “Communist activities.” It isn’t known what evidence the government used to conclude that the murders were committed by some “aliens” and that partisans of the Lithuanian Activists Front were not involved in the massacre.

Page 19. Protocol #6, June 30, 1941:

“Having heard Kaunas city commandant colonel Bobelis on the formation of an auxiliary police battalion (Hilfstpolizeidienstbatalion) and a Jewish concentration camp, the Cabinet resolved:

1. To provide advance payment for the maintenance of the battalion for 10 days, calculating this at 7,492 rubles per day; later, to allocate funds for this purpose in accordance with estimates to be provided.

2. To approve the establishment of a Jewish concentration camp and to assign the direction of its creation to vice-minister of public works Mr. Švilpa in cooperation with colonel Bobelis.”

Colonel Jurgis Bobelis was in charge of the creation of a concentration camp in Kaunas’s Seventh Fort and a Lithuanian Police Battalion. This special police battalion was responsible for guarding and exterminating Jews. The Provisional Government paid the battalion for its service. Battalion officers carried out the murders. From the establishment of the extermination camp till its closure on September 10, 1941, battalion officers killed up to 5,000 Kaunas Jews.

Page 135. Appendix #1 to protocol #31 of the Cabinet of Ministers of Lithuania, August 1, 1941. The document named “Regulations on the Status of the Jews” was adopted.

The “Regulations on the Status of the Jews” adopted by the Provisional Government, regulating the life of the Jews in Lithuania, were in essence similar to the Nuremberg racial laws passed in Nazi Germany in 1935. Under these regulations the Jews of Lithuania were deprived of all human and civil rights. The adoption of this misanthropic resolution was the last chance for the Provisional Government to convince the Nazi administration of the PG’s loyalty to occupational authorities. But it was too late: the attempt to be two things at once – both Nazi and national Lithuanian – failed: the PG was caught in the middle and forced to resign by the Nazi administration. Since it was not anti-Nazi, however, its ministers did not face any reprisals.

◊

“Our Heroes” are Not “Your Heroes”

Prof. Aleksandravičius did not reject the journalist’s words about the peculiar role of “the Jews” who were allegedly protesting against the reburial with full honors of Ambrazevičius. The academic interpreted Bartusavičius’s statement in his own way:

“This was caused by a disconnect in the memory of Lithuanians and Jews. By reburying Brazaitis, we wanted to show that the drama of Lithuanians hasn’t ended yet. All of our heroes who during that tragic period of history attempted to raise the flag of Lithuanian independence were forced into compromises with stronger powers. These circumstances enable people to portray them in terms of the great evil of those times.”

It turns out that the problem is not in “our heroes,” but in the fact that Jews and Lithuanians understand the same historical events differently, and someone “paints” the gleaming white robes of our heroes with grotesque colors.

So, whom does Aleksandravičius call “our heroes?” The Prime Minister and PG ministers? Police Battalion officers in the Seventh Fort?

Doesn’t historian Aleksandravičius know that “our heroes,” i.e., the PG, made a criminal decision to establish an extermination camp at the Seventh Fort? That the Lithuanian police began the “orderly and planned” murder of the Jews? That from that moment on a new phase in the Holocaust – the organized massacre of the Jews – began? With his signature on the documents, “our hero” Ambrazevičius turned the mass murder of Jews into a legalized procedure which was performed by other of “our heroes” dressed in Lithuanian national police uniform with the tricolor stripe of the Lithuanian flag on their sleeves. Ambrazevičius did not admit his guilt in the mass murder of the Lithuanian Jews to the end of his life.

Who knows what those “heroes of ours” thought during the sacrifice of the lives of thousands of Jews? Did they think only of “raising the banner of independence,” as historian Aleksandravičius affirmed? But in so doing they turned their country into one of the European factories for exterminating the Jews, into a vast cemetery of wholly innocent people of both sexes and all ages, from very old men to babies. The results indicate that this prospect did not scare “our heroes,” neither in the PG nor in the police battalions.

Who exactly, according to the historian, tried to “raise the banner of independence?” Is the scholar not familiar with the Lithuanian Activists Front instructions called Guidelines for the Liberation of Lithuania, dated March 24, 1941? These instructions were published in the Lithuanian language in Liudas Truska and Vigantas Vareikis’s book The Preconditions for the Holocaust. Anti-Semitism in Lithuania. The book is published in English, too (Liudas Truska, Vygantas Vareikis. Holokausto prielaidos. Antisemitizmas Lietuvoje, “The Preconditions for the Holocaust”. Margi raštai, Vilnius, 2004).

These Lithuanian Activists Front instructions, these Guidelines for the Liberation of Lithuania, dated March 24, 1941, stated:

“It is important to use the occasion and get rid of the Jews. Therefore, you should create such a heavy atmosphere for the Jews in the country that not a Jew could dare even think that he can still have rights or the opportunity to live in the new Lithuania. The goal is to force all the Jews to flee from Lithuania along with red Russians. The more of them that disappear from Lithuania on this occasion, the easier it will be to get rid of them completely in the end. The hospitality to the Jews in Lithuania once provided by Vytautas the Great is abolished forever for their recurring betrayal of the Lithuanian people.”

The author of these instructions was Kazys Škirpa, founder of the Lithuanian Activist Front, whose task was to organize the anti-Soviet uprising and assist Hitler’s approaching troops. Škirpa was the first to come up with the idea to create the Provisional Government of Lithuania and to establish a Lithuanian dictatorship similar to those in France, Norway and the countries of central and southern Europe (Slovakia, Hungary, Bulgaria). He also outlined the requisite members of the government he was to head.

German troops moved into Lithuania lightning-flash-like, blitzkrieg-style. Anti-Soviet rebels were the first to massacre Jews in settlements not yet occupied by the Germans.

Trying to dress “their” rebels in white, those among the current crop of Lithuanian historians who carry out political agendas claim that the Nazi secret services prepared “their own rebels” to carry out provocations and pogroms, and they allegedly instigated the massacre at the Lietūkis Garage and in Vilijampolė (Slobodka), even though there is no convincing evidence for their version of events. In the scenario they paint, the PG and LAF should even have stopped the provocations, pogroms and atrocities…

Prof. Aleksandravičius has no illusions about the prospects for somehow “forgetting” the Holocaust, for shielding and not remembering anything about this tragedy. This attempt recalls attempts by right-wing and radical-right politicians of our time to equate the Holocaust with Stalinist repressions.

One can do nothing but agree with Aleksandravičius when he says:

“The Holocaust is and will remain at the center of the memory of Lithuanians, even if we try to avoid talking about in all sorts of ways.”

But it’s not about just how long the Holocaust will stay in the core memory of Lithuanians. “Family folklore” has huge importance in historical memory: family stories and oral transmission of life experience are of great educational value. What did past generations tell their descendants about the Holocaust? What sort of memory did they generate in their children and grandchildren? What do today’s parents tell their children and grandchildren about the Holocaust? What will today’s children and grandchildren think when they learn that the facts from the history books and their teachers do not coincide with family stories?

Apparently, today’s formalism, constituting “a reasonable, rational lie” mixed up with the truth in history books, is taking control of schoolchildren’s consciousness and conception of the time and events of World War II; it allows them to talk of the events of 72 years ago easily and without any problems. It is evident how it will affect the future of the country. Instead of acknowledging the bloody nightmare of 1941-1944, which has no analogues in the long history of Lithuania, they will be presented with delirious tales and an explosive cocktail of lies and truths mixed up together in the textbooks.

Aleksandravičius remains silent about this. At the same time the doctor issues a prescription: “Lithuanians and Jews need to learn to understand better the memory of one another.” What does “understand the memory of one another” mean? This is a controversial issue: the murderers and their apologists find justification for themselves. Their memory is shorter and more pliant to their masters. But how, for instance, can one teach family and friends to respect the memory of the killers? What do parents, children, grandchildren know about the past of the murderers?

The professor’s following words seem even weirder:

“I understand the Jews’ reaction, it is based on a simplified, schematic opinion of the Provisional Government. But we can not weed its anti-Semitic statements out of the history.”

Let’s ignore the historian’s remark about the “simplified” opinion of the Jews for the moment. It is indeed strange to hear this doctor of social sciences call the resolutions “statements.” A statement might appear to be mere foolishness, but a resolution is an unforgivable crime.

Bartusavičius reminds the historian:

“But Brazaitis in his memoirs told about how he even tried to oppose the wave of antisemitism.”

The professor reasonably rejects the journalist’s “hint”:

“Those memoirs were written after World War II, in emigration, so they are only a secondary source of information.”

And then he immediately agrees with the journalist, surprising readers:

“But later activity by Brazaitis showed that he was no anti-Semite. He didn’t even enter into compromises with the Nazis to the extent Lithuanian Activist Front founder Kazys Škirpa did.”

Thus the professor and the journalist find common ground. But who is interested in the question of whether the interim Prime Minister was an antisemite or not, whether he compromised with someone or not, since in placing his signature on them, Ambrazevičius made legal the documents that doomed the Jew minority to death?

The executions of Jews at the Seventh Fort began on the first day of his “work.” It’s not important at all whether Ambrazevičius wept over his signature on the resolution or rubbed his hands with glee. The PG’s resolution on the establishment of the Lithuanian Police Battalion and the extermination camp was a death sentence for Jewish citizens. This resolution was tantamount to legal permission to murder Jews.

But then, Aleksandravičius also calls the Provisional Government’s resolutions verbal compromises. He says:

“I only see the drama of a person who was not able to foresee that it was dangerous to even enter into verbal compromises with the great powers of evil for the sake of the ideals of Lithuanian freedom.”

What “verbal compromises” does Aleksandravičius find to justify Ambrazevičius? Of what ideals of freedom does a person dream, when he signs the death sentences of people who called Lithuania home for seven centuries?

Aleksandravičius undertakes the role of PR agent for a defendant:

“This was an extraordinarily cultured person, but the cataclysms of history fated him to become the head of a government that had no power, in whose documents it is possible to come across inscriptions that violate principles of humanitarianism.”

Well, he has already come to “an extraordinary cultured man,” as if the great culture of Bach and Goethe prevented, say, the PhD Goebbels from committing horrendous crimes! What documents, except these texts, has Aleksandravičius found? What does “fated him to become” mean? Who dragged him by the hand or at the point of a gun to the prime minister’s chair? Among the PG members he was probably the only one who had neither administrative experience nor specific knowledge of the situation: if his head had not swollen at the prospect of becoming the savior of Lithuania. If he hadn’t wanted to become “king for a day,” no one would have forced him.

◊

How Ambrazevičius Became Prime Minister

The name of Ambrazevičius was not among the PG members announced by Leonas Prapuolenis from the studio of Kaunas radio on 23 June 1941. Kaunas radio technician Vytautas Bagdonavičius simultaneously recorded on a vinyl gramophone record the list of ministers, in this way saving it for the history of Lithuania. The surname Ambrazevičius was absent from that list. Kazys Škirpa, former chief of staff of the Lithuanian army, former ambassador extraordinaire and plenipotentiary minister of independent Lithuania to Nazi Germany, was declared the PG’s prime minister; he was known throughout Lithuania. There is no evidence to suggest that Ambrazevičius enjoyed the most authority among the ministers.

At first there was need for this head of the government, but Škirpa did not appear in Kaunas on June 23, 1941. His absence sent a very disturbing signal to the rest of the PG.

In Škirpa’s absence the situation became uncertain and an atmosphere of confusion set in. They felt the lack of prospects for the further work of the government. Circumstances required good knowledge and strong connections among the upper Nazi echelons where the fate of occupied Lithuania was to be decided.

Škirpa was an insider in the Nazi secret services and the German ruling elite. He was acquainted with Ribbentrop and Hitler and met with them more than once as the ambassador of the independent Republic of Lithuania.

Certainly, none of the ministers were eager to take on responsibility for the fate of the national government in Lithuania, all the more so because it was supposed to be only a temporary substitution for Škirpa himself. It was clear to all ministers that Škirpa was going to appear in Kaunas. After creating the Lithuanian Activist Front, preparing a revolt against the Soviets, developing the strategy of the revolt, creating the provisional government and preparing its proclamation, he couldn’t just stop at the very beginning of the road and, as athletes put it, “throw the game.” Ambrazevičius was chosen interim prime minister. Putting the least experienced at a disadvantage is a common ploy by experienced bureaucrats.

So Ambrazevičius took on the duties of the PG’s prime minister. Why did he agree to head the government, having no foundation for doing so? Most likely it was due to his inexperience.

◊

Back to the Interview

Out of the blue, the Lietuvos rytas correspondent throws Aleksandravičius a life belt:

“Perhaps it should have been stressed first of all that the person being reburied was an individual who sought an exit from the complex plight of history, rather than the head of a government?”

Aleksandravičius latches on to the prompt as if it were a life belt.

“Truly it should be stressed that at that time we did not have a state which was capable of protecting its citizens even minimally. The Provisional Government issued a declaration of independence, and in so doing seemingly also declared the state of Lithuania was being restored, but in fact it had no control whatsoever.”

But then he catches himself. After all, as a trained academic, he should understand that if a group of people make a declaration of independence but possess no authority or independence in reality, it means they are simply lying to the public.

So the scholar quickly changes the subject and says indignantly:

“It is as if our right to have heroes who could be judged simply as heroes has been taken away from us.”

He adds:

“We are not unique in this respect. The Ukrainians, for example, built a monument to Stepan Bandera, he fought against the Nazis and fought against the Soviets, though he was involved in the mass murder of Jews and Poles.”

Indeed, Bandera, as they say now, was “cooler” than Ambrazevičius. He killed left and right, everyone who came within eyesight. His sharp saber cut off а lot of heads. This Ukrainian “hero” bothered himself particularly much with Jewish heads. Unlike him, “our hero” did not kill anyone personally, did not even fight against the Soviets, spoke to the Germans in a very civilized manner, did not touch Poles. Well, it was just the Jews…

Overall, nothing became clearer after the conversation between Lietuvos rytas correspondent Bartusavičius and Professor Aleksandravičius. Bartusevičius’s phrase that “the Jews’ reaction” led to the decision by Vytautas Magnus University not to allow a scheduled conference on Brazaitis there stands unrefuted.

Some twenty days later an “Open Letter” was published, signed by 41 prominent scientists, artists and public figures, criticizing the reburial:

“We, the undersigned, citizens of Lithuania, are definitely against the decision by the Government of the Republic of Lithuania, the Seimas of the Republic, Kaunas and other executives officials to honor the memory of Juozas Ambrazevičius, the head of the Provisional Government of Lithuania June-August 1941, who called himself Brazaitis in exile.”

The names of those who signed the protest are listed in alphabetical order, and therefore the name Aleksandravičius happens to come first. Such is the fate of history.

◊

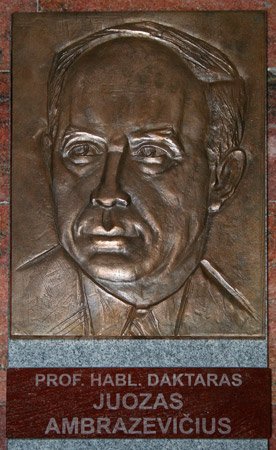

Lithuanian president Dalia Grybauskaitė didn’t participate in the reburial ceremonies, yet on behalf of the country she expressed her opinion on Ambrazevičius, posthumously awarding Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis the Order of the Cross of Vytis, first degree, by her decree of June 26, 2009. Lecture hall 608 at Kaunas’s Vytautas Magnus University is named after Ambrazevičius. A bas-relief was erected in his honor in the same building. His name was bestowed upon streets in Kaunas and Marijampolė.

Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius and his government made up of Homeland Union / Conservatives and Lithuanian Christian Democrats did not participate in the official reburial events, although, despite public protests, they allocated the money to conduct this solemn sanctification of his memory. The government was, as they say, “with him with all their hearts.”

A similar reburial took place eighteen years ago, in 1995, marking the 100th anniversary of Kazys Škirpa’s birth. The ashes of the author of the “Guidelines for the Liberation of Lithuania,” a document saturated with antisemitism, were brought from the United States to Kaunas and solemnly reburied at the Petrašiūnai cemetery. Then-prime minister of independent Lithuania Adolfas Sleževičius and defense minister Linas Linkevičius (now minister of the foreign affairs) gave speeches during the ceremony. The lowering of the ashes into the grave was accompanied by the Lithuanian national anthem and a gun salute. Today Škirpa’s grave is adorned with one of the richest and most impressive of the monuments there, always attracting visitors’ attention. Škirpa’s name was immortalized in a street name in central Vilnius and a street in Kaunas. Moreover, a memorial plaque marks house no. 25 on Gedimino Street, in the center of Kaunas, bearing the following inscription:

“In this house in 1925-1926 Kazys Škirpa worked, the creator of the Lithuanian Armed Forces, participant of the struggle for independence, a member of the Constituent Seimas, Chief of Staff, diplomat, leader of the Lithuanian Activist Front, President of the Provisional Government of Lithuania, Knight of the Cross of Vytis, Colonel of the General Staff (1895-1979).”

This is the reality of political life in Lithuania.

◊

A Word about the Real Heroes

Aleksandravičius states: “All of our heroes” who during that tragic period of history attempted to raise the flag of Lithuanian independence “were forced” to make comprises with stronger powers.

Nevertheless, there really were self-sacrificing people in Lithuania, people who did not raise or lower any flags, but also did not compromise with “stronger powers,” as the historian delicately calls groveling before the Nazi occupiers. At all times of Lithuanian history there have been people who did not compromise when it came to their own conscience and humanity.

They are humanists, people of great soul and nobility. They did not even suspect that at that creepy time they were real heroes of their country and their people. Ordinary people from different strata of the non-Jewish population of Lithuania saved the doomed Jews. Their feat was not one of minutes or hours: for months, day after day, for three years, they risked their own lives to save the lives of Jews. They defended the honor of their people, not of “our heroes” imposed “from above” on Lithuanians. In terrible times these heroes shared their shelters, food and the warmth of their souls with the persecuted Jews, risking not only their lives but also the lives of all members of their families. At all times these rescuers have remained the true heroes of Lithuania, those who selflessly resisted Nazism, violence and fear. Sadly, there are so few of them, but, fortunately, these holy people exist! They do! They are the honor and conscience of the Lithuanian people in the era of the Holocaust.

During the Cold War, when the Soviet Union with Lithuania as part of it was separated from the whole civilized world, the employees of Yad Vashem (the National Institute of Victims of Nazism and the Heroes of the Resistance in Israel) miraculously managed to find out the names of more than 150 people who saved Jews. Rescuers were awarded the highest distinction: Righteous among the Nations. This title is given to people who risked their own lives to save others from death.

After the restoration of independence, Lithuania managed to track down more rescuers of Jews, known as Righteous Among the Nations.

In Lithuania, the rescuers of Jews, Lithuanian Righteous among the Nations included, are awarded the Life Saving Cross. Presidents of Lithuania Algirdas Brazauskas, Valdas Adamkus, Rolandas Paksas and Dalia Grybauskaitė have presented this award to 1,246 people so far.

Yad Vashem on its website recognized 844 rescuers from Lithuania as of 1 January 2013. The number has been growing this year.