O P I N I O N

by Roland Binet (Braine-l’Alleud, Belgium)

When I was in New York last year, I saw an extraordinary exhibition of paintings by Marc Chagall, “War, Exile and Love” at the Jewish Museum. The focus was on the works he produced during his years of exile in the United States. This exhibition, well attended, shed an interesting light on what the artist knew about the horrific events unfolding in Europe at the time of his sojourn in the United States.

Chagall had always been a kind of visionary painter. He had never hesitated before World War II to tackle political matters dealing with his home country, Russia (his native towns are in today’s northeastern Belarus) or the fate of the Jews. Already, in the 1930s, some of his most reputed paintings showed feelings of despondency, a foreboding of horrid events to occur in the future.

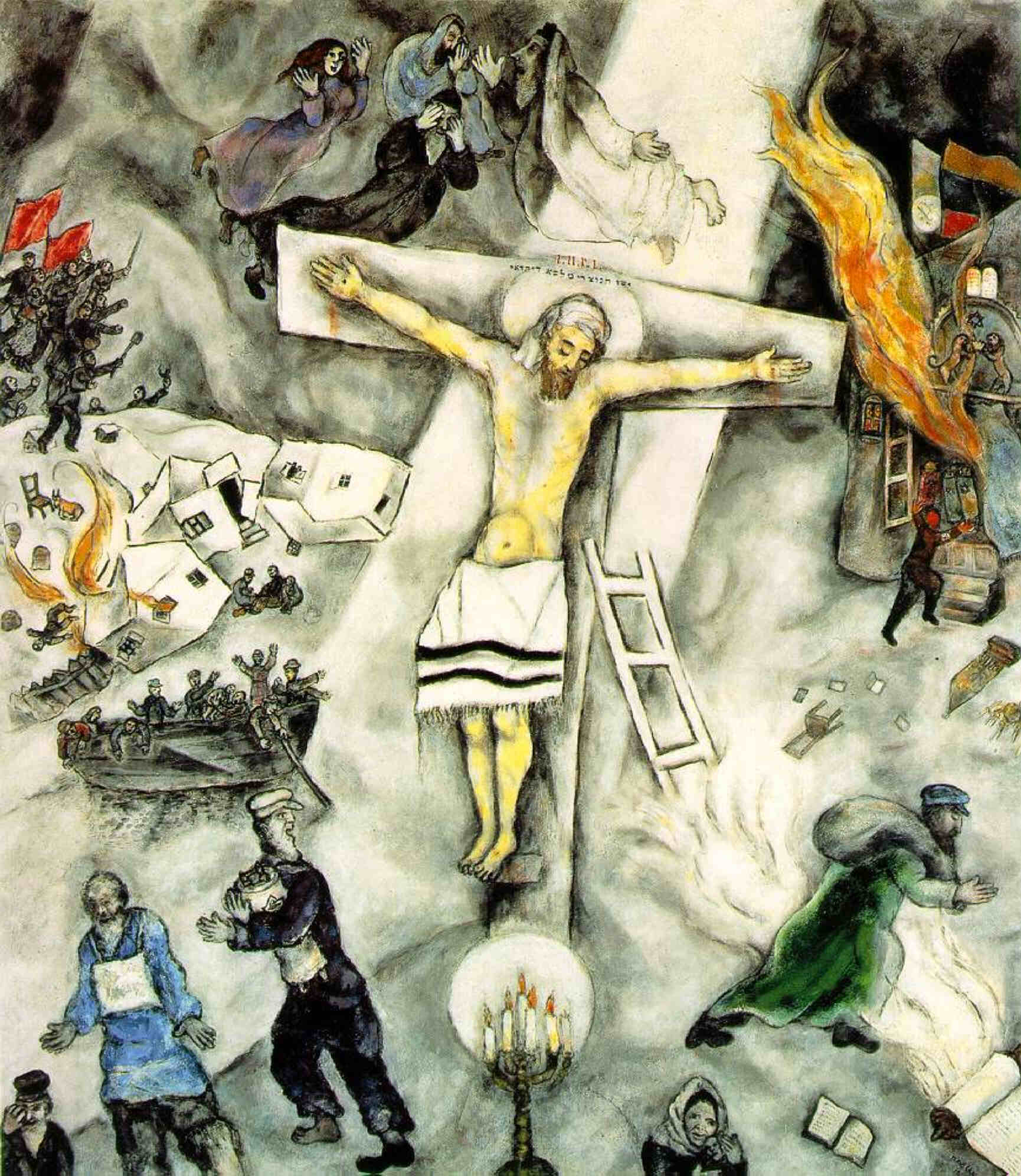

This gift to illustrate a past that is also a portent is genuinely awe-inspiring in such paintings as “Solitude” (1933/34) and “The White Crucifixion” (1938). The Crucifixion has the figure of the Christ symbolizing the suffering inflicted on the Jews. In that work, the main horrifying pictorial symbols directly relate to a pogrom and destruction of villages. In this particular painting, it is the red-flag waving revolutionaries who commit acts of violence against the Jews. But this painting alone can also symbolize the living hell the Jews had to go through, mostly in the Eastern European countries, where parts of the local populations sometimes resorted to pogroms.

On a wall in the Jewish Museum, we can read what Chagall thought of the savagery the Germans unleashed on Europe:

- I see them: trudging alone in rags,

- Barefoot on mute rods,

- The brothers of Israels, Pissarro,

- Modigliani, our brothers, — pushed

- With ropes

- By the sons of Dürer, Cranach

- And Holbein – to death in the

- Crematoria.

Numerous paintings in that remarkable exhibition dealt with the fate of the Jews in Europe during World War II. A recurrent symbol is the figure of a mother holding a child in her arms. What better example to describe the helplessness of persons about to be killed? Most works, though, were outstanding depictions of pogroms, people fleeing from danger, fires, destructions of lives and properties.

But, a few weeks after having seen such an exceptional exhibition, I thought that in fact it was ironic but also sad that Chagall had learned of the fate of the European Jews, reacting in a typical artistic way by creating his pictorial visions of the horror the Jews had to suffer. Similarly, the German writer Thomas Mann — also living in the United States at the time — had also heard news of the pogroms and massacres of the Jews in Europe and he gave a speech on the radio about what would later be called the Holocaust. Others, however, even better informed of events on the ground in Europe kept silent.

There is now ample documentation about what the principal allied leaders of the United Kingdom and the United States knew about what really was happening on the killing fields of the USSR and in the killing factories in Poland during the war. Already at the beginning of the 1980s, Martin Gilbert had written a book about the shameful silence of the Allies related to Auschwitz. As early as 1941, the British authorities knew about what was happening in the killing fields of the USSR and the huge numbers of Jewish victims. They knew about the ghettos being erected, simply because very early British technicians had already cracked some German military codes and had been able to read dispatches from SS units (there is an example of such a document in the British archives which was kept for half a century years marked “MOST SECRET – to be kept under lock and key”).[1] But, there were also written reports that the Allies received. Jan Karski, a member of the Polish Armia Krajowa, was sent to the United Kingdom and to the United States and spoke personally with authorities at the levels of Secretary of State or Under Secretary of State. A special envoy from Poland’s Bund – Szmul Zygielbojm – went to the UK and spoke with Jewish organizations, describing the horrors that were being committed against the Jews in Poland. He was not believed. Disgusted and in complete despair about the silence of his own brethren, he committed suicide. Two men from Slovakia, Rudolf Vrba and Franz Wetzler, succeeded in escaping from Auschwitz. They wrote a precise report on April 25, 1944, which was sent to Churchill, the president of the United States and Pope Pius XII.[2] There had also been a report about the hell that was Beŀżec submitted to the Vatican religious authorities by the SS captain Kurt Gerstein, a Nazi with a conscience.[3]

Some would say that the Allies kept silent because they did not want the Germans to learn that they had cracked the “Enigma” as well as other military codes and knew everything the German troops, SD, SS and Einsatzgruppen units in the field did and cabled or radioed.

Let us remember first that prior to the Second World War, most West European countries, as well as the United States, refused entry to Jews who had succeeded in escaping from Germany or Austria. In Palestine, the British blockaded the entry for those Jews fortunate or rich enough who could have found a way to the Land of Israel via Spain, Portugal, Romania or Turkey. And in some countries, for the Jews who had received some authorization to stay, they remained foreigners. In Belgium, for instance, the local and German authorities in charge of Jewish affairs mainly deported the “foreign” Jews (non-citizens of Belgium),who fled Nazi Germany.

During the war, the Allies could have bombed the principal railways leading to the death camps and gas chambers, and principally Auschwitz-Birkenau which had been filmed by allied pilots. But most important, the leaders of the UK and the US could have taken a firm stand, very early in the war, at the end of 1941 (when the United States had declared war on Germany and Italy after having been attacked by Japan and Hitler’s declaration of war on America) or at the beginning of 1942. They could have said in essence that the German nation as a whole would have been held responsible for the crimes committed against the Jews and the other civilian populations in the USSR as well in all occupied countries of West Europe, and thus subject to massive retaliation if these massacres were not ended right away. The Allies could have targeted the symbols of power in Berlin, the lairs of the Nazi leaders Goering, Goebbels, Speer, bombed the Reichskanzlerei and killed Hitler before he chose to live in the underground bunker. They could have destroyed totally the headquarters of the Gestapo and SS, thus rendering the execution of the “task” of destruction of the Jews more difficult. They could have bombed Zossen south of Berlin, the Headquarters of the Wehrmacht, out of existence. They should have been creative and thought about ways to disrupt the mechanics of the massacres of Jews being perpetrated in Europe or, at least, ways of slowing them when it became known in 1942 that death trains were deporting thousands of Jews to the gas chambers from Western Europe or that round-ups in the Polish and Soviet ghettos led to mass massacres in the gas chambers or in the killing pits.

What lessons can we draw from such a criminal silence of the Allies?

Artists have a conscience and act accordingly in their own particular manner. Political leaders make political choices. Conscience does not play a role in what they decide, only realpolitik. They revert, in time of crises, to self-centeredness and to the protection of their ethnic populations. And the Jews, in whatever country they lived in at the time of the war had always been considered “foreign” in various demonstrable senses.

Of course, when the Allies put the Nazi leaders on trial in Nurnberg, they never mentioned what they had known during the war. They never explained why they kept silent.

And even now, most people in Europe do not know anything about that terrible and horrible reality: the Allied leaders, duly informed of what was happening to the Jews and other “sub-species” in occupied Europe kept silent while millions of innocent civilians were put to death.

This is a shame and a blot on the final victory against the Nazi beast. And it is a shame that so little is known about these historical facts.