O P I N I O N

by Eleonora Groisman

The author is president of The Ukrainian Independent Council of Jewish Women, and edits the newspaper Jewish Kiev. Authorized translation into English provided by the author is by Mr. Valery Novoselsky (executive editor of Public Diplomacy Network and of Roma Virtual Network). See:

http://evreiskiy.kiev.ua

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/Jewish_Daily_News/message/92

http://www.facebook.com/evreiskiy.kiev.ua

Appeal to the representatives of international governmental and non-governmental organizations by a group of social organizations and citizens of different countries concerned about the growth of antisemitism in Ukraine:

In the 2012 elections to the Verkhovna Rada the far-right nationalist Svoboda party passed. To date, the Svoboda fraction has 37 parliament members, within the total of 450 parliament members.

The last time I looked at the international petition site I set up

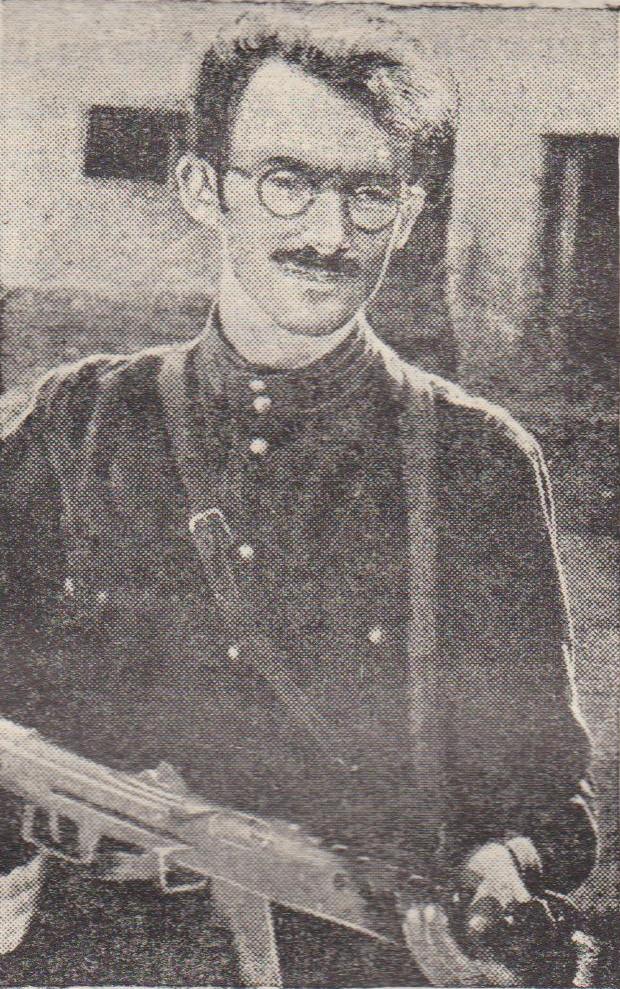

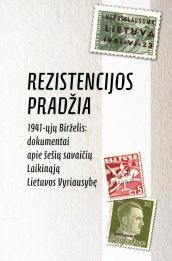

The last time I looked at the international petition site I set up  MEP Vytautas Landsbergis, former speaker of the Lithuanian parliament and leader of the Lithuanian independence movement in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, unveiled his latest polemic at a ceremony cum press conference held on the first floor of the Signatarų Namai building in Vilnius’s Old Town on September 11, 2012, the historic site where Lithuanian independence was proclaimed from the balcony to the street below sometime around February 16, 1918.

MEP Vytautas Landsbergis, former speaker of the Lithuanian parliament and leader of the Lithuanian independence movement in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, unveiled his latest polemic at a ceremony cum press conference held on the first floor of the Signatarų Namai building in Vilnius’s Old Town on September 11, 2012, the historic site where Lithuanian independence was proclaimed from the balcony to the street below sometime around February 16, 1918.