O P I N I O N / C O L L A B O R A T O R S G L O R I F I E D

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

◊

In the midst of this past summer’s heatwave here in Lithuania, Delfi.lt, one of the most popular news portals in the land, exploded with discussions on commemorations and memorials for Nazi collaborators in our country. Rimvydas Valatka, a columnist for the portal and signatory of the Declaration of Independence, started it all with his article of 26 July. The “current events background” was the recent removal of the controversial Soviet-era statues of soldiers on Vilnius’s Green Bridge. Valatka, a veteran of Lithuanian journalism with the rarefied street-cred of a Declaration of Independence signatory, appealed for removal of the memorial plaque for Nazi collaborator Jonas Noreika (“Generolas Vėtra”) from a central Vilnius library building, and wrote about a petition for its removal signed by a group of intellectuals and public figures, and addressed to the mayor of Vilnius as well as to the director of the relevant library (Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences), where the plaque hangs prominently in the heart of Lithuania’s capital.

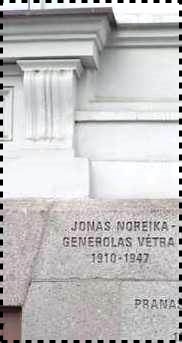

The stone honoring Holocaust collaborator Jonas Noreika tops the lot on the facade of the Genocide Museum on Gedimino Boulevard in the Lithuanian capital, a stone’s throw from the nation’s parliament. When are we going to stop glorifying those who helped annihilate Lithuanian Jewry during the Holocaust? When is this going to come down?

The stone honoring Holocaust collaborator Jonas Noreika tops the lot on the facade of the Genocide Museum on Gedimino Boulevard in the Lithuanian capital, a stone’s throw from the nation’s parliament. When are we going to stop glorifying those who helped annihilate Lithuanian Jewry during the Holocaust? When is this going to come down?

The text of the article is somewhat odd, almost as if Valatka was avoiding talking about the actual (to-this-day “secret”) text of the petition of the group of intellectuals. But the list of signatories is not secret. He mentions the document that was to have been (was? will be?) signed by “A. Ramanauskas, L. Donskis, V. Toleikis, D. Puslys, D. Udrys, A. Imbrasas, A. A. Jonynas, S. Sužiedėlis, S. Trilupaitytė, T. Venclova, V. Kelertienė, E. Bendikaitė, J. Lagas, J. Žilinskas, S. Kanovičius, Š. Liekis, V. Gaidamavičius, A. Žukauskas, D. Varnaitė, and other famous people.”

The article includes Jonas Noreika’s biography: pre-war activities; participation in the 1941 “uprising”; serving as the Šiauliai county governor; imprisonment at Stutthof; liberation and service in the Red Army; his postwar transformation into “Generolas Vėtra” (literally, General Storm). He was arrested by Soviet authorities and executed on 16 February 1947.

His modern accolades are mentioned, as well: “President Algirdas Brazauskas posthumously awarded him the Order of the Cross of Vytis of the first rank. Šukioniai Secondary School was named after him, and a memorial stone was unveiled in Šiauliai.”

The text of the Delfi.lt article continues:

But there are some unheroic facts even in the official biography. Noreika signed the decree to establish a Jewish ghetto in Žagarė on 22 August 1941. Joniškis mayor A. Gedvilas, appointed by Noreika, carried out his orders to move the Jews of Joniškis to Žagarė. Soldiers that arrived at Joniškis shot to death several hundred Jews of Lithuanian citizenship on the spot. The rest were moved to Žagarė. There, they were also executed, only later.

According to R. Valatka (and quite rightly!), “These facts are enough to de-heroize any person.” He then mentions the execution of Plungė’s Jews, described by A. Pakalniškis, and the accusations of massacring Plungė’s Jews, of which Noreika was accused by Der Spiegel. Accusations by A. Lipšicas of executing 5,100 Jews in Šiauliai county are also mentioned.

Historian Arūnas Bubnys’ doubts about the relation between Jonas Noreika’s “anti-Nazi activities” (such are the terms in these cases of the state-sponsored “Genocide Center”) and his imprisonment at Stutthof are here, as well. P. Narutis’s doubts about the activities of insurgents at Plungė in 1941 are recalled, as well as the antisemitic brochure “Head Held High, Lithuanian!” that was written by Noreika in the pre-war period. The whole array of facts is really similar to an article I wrote several years ago (the English version appeared here in Defending History), but Valatka does not mention any sources except the appeal (i.e. the still unknown text…) signed by the galaxy of intellectuals. The intellectuals allegedly “quote conclusions on Noreika’s wartime activities delivered by the director of the Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania (LGGRTC). This institution does not deny any of the facts of Noreika’s biography. However, for some reason it does not maintain that Noreika took part in organizing the Jewish genocide.”

A certain inevitable lack of clarity aside (he is talking about a summer 2015 letter from a group of intellectuals whose content is somehow secret), Valatka’s article is actually truily valuable. The author enjoys an authoritative position among journalists – he has been the editor-in-chief of a few major Lithuanian papers and portals – and his time as a politician is also remembered with high regard. Furthermore, Valatka is educated as a historian, which means he understands the historical nature of this problem and is able to unambiguously stress the most important points:

We must acknowledge and come to terms with the picture of Generolas Vėtra that Captain J. Noreika as he actually was. Although he enjoyed better conditions than most people in Nazi prisons, he still served time at Stutthof. He was a brave guerilla fighter and a victim of the NKVD. At the same time, however, he wrote antisemitic proclamations and collaborated with the Nazis at the highest level. He organized ghettos and, if we are to believe A. Pakalniškis – and no one has yet disproved his stance – arranged the massacre of Plungė’s Jews. Yes, Generolas Vėtra as he was can never be a Lithuanian hero. Memorial plaques and posthumous orders dedicated to him by the state are nonsense. Nevertheless, Generolas Vėtra as he was is our history. Actual 3-D history. His story is another horror tale about being near the gates of hell, and possibly even past them.

Of course, there are confusion-inducing bits in Valatka’s article that fuel the polemic fires, for example, the beginning of the article in which he compares the recent (actual) removal of the Green Bridge statues of Soviet soldiers to (hoped-for) removal of Noreika’s memorial plaque Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences.

I must admit I have not seen the secret document signed by these famous intellectuals. Hopefully it will finally be published even now, as summer turns to autumn. It was not for want of attempts to locate it. I asked Sergejus Kanovičius (Brussels), who organized the appeal, and he responded that the text of the appeal “will not be made public” (!) and that the letter has already been sent (!).

Since Valatka in his article mentions Birutė Burauskaitė’s — Genocide Center director’s — response to the appeal, we now have material for reconstructing the contents of the top-secret document. Or at least guessing. Perhaps the intellectuals who composed the secret document refer to sources referred to by Grant Arthur Gochin in his own blog in his appeal to the Vilnius mayor (and his subsequent article in the Jerusalem Post). Gochin references the article in Der Spiegel and my own article in Defending History. He also published Burauskaitė’s response to his inquiries on memorials to Noreika in the Lithuanian capital. In her response, the director assumes that Pakalniškis’ memoirs are “unreliable,” although she also reveals the historical data that proves that Pakalniškis was right on the mark. Burauskaitė admits that Noreika’s decrees existed but offers curious interpretations of them: “The surviving decrees signed by Noreika order Jews’ isolation and not organization of mass executions. Isolating the Jews and mass executions are not seen as historiographically identical.” The director also admits that “Noreika managed issues related to Jewish wealth” [emphasis added].

Genocide Center director Burauskaitė’s paragraph begins with something close to truth, but ends in an attempt to deny that very same truth in the usual spirit of the Genocide Center and our state-sponsored responsibility-deflecting official historiography:

Isolation of Jews, i.e., their ghettoization, meant that the Nazis were controlling the Jews through Lithuanian officials. This circumstance allowed the Nazi regime to proceed towards executions, i.e., elimination of the Jews as an undesired group. There is no information confirming that the Šiauliai county governor J. Noreika was related to organizing and carrying out mass executions. It was not possible for him to take up such tasks, since the German occupation regime did not rely on Lithuanian civil authorities to organize the Jewish elimination, and used police structures, auxiliary police, and the self-defense battalion instead. J. Noreika led a civil institution and not a police structure.

I have no doubts that the signatories of the unpublished appeal for the memorials to be removed had no trouble in realizing that these arguments by the Genocide Center director are woefully inadequate and do not do our country’s name a service. Nevertheless, they are clever people. Among them one can find such names as Saulius Sužiedėlis, professor emeritus of history at Millersville University, and co-author of The Persecution and Mass Murder of Lithuanian Jews during Summer and Fall of 1941, a research project commissioned by the state-sponsored Commission for the Evaluation of the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupation Regimes in Lithuania (the so-called “Red-Brown Commission”).

So it appears that the case was taken up by erudites. But that of course did not stop a debate erupting in Delfi.lt.

The first to join was independence fighter Jonas Burokas (on 29 July). His arguments are simple:

On 3 August 1941, Jonas Noreika was appointed governor of Šiauliai county not by Nazi Germany, but by Lithuanian Provisional Government, legitimately and legally formed after the successful anti-Soviet uprising.” […] “The Žagarė ghetto was established a month before Noreika was appointed. His decree simply repeated the Nazi orders, while personally he put all possible effort to stopping Nazi plans.

There is just one little thing missing: the smallest actual example of how Noreika tried to sabotage the extermination of the Jewish citizens of Lithuania, in which he himself played a documented part. Attempts are once again made at covering these by referring to the failed conscription to an SS forcein Lithuania, which happened a few years later and has no relevance to the massive 1941 participation in the annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry. Again, the part in which Noreika’s role in this would be clarified, is missing. And, as if once again amnesia-prone about Noreika’s decrees, Burokas states that “There is no genuine data in the archives that could prove Noreika taking part in the Jewish genocide.” As for Plungė, a backed-by-nothing nonsense statement from a dozen years ago is repeated as if repetition will help the case: “Noreika was not in Plungė at the time.”

After some time, Vytautas Sinica got involved (6 August 2015). He spun a polemic out of several not really related threads: the famous former dissident A. Terleckas’s unsuccessful court case against an anonymous internet commentator, the Green Bridge statues, and arguments presented by Burokas (the same arguments about Noreika’s supposed innocence rehashed in Burauskaitė’s own response). I would consider this a bit disrespectful to the readers and the general public, since the Genocide Center director’s response in full is still unknown to Delfi.lt readers!

The next participant in this conversation was Ramūnas Bogdanas (14 August 2015). He went so far as to declare “tarnishing” Noreika’s biography a part of some kind of Russian Putinist information warfare, and even as revenge for removing the Green Bridge statues. A paragraph directed at your truly (and by implication, Defending History) was duly included.

After Vilnius removed the four rusted statues that were so important to Moscow, the retaliation was aimed at our delicate spots. Less than a week later, there appeared a flood of articles about Lithuania’s post-war partisan fighter Jonas Noreika, a.k.a., General Vėtra. Our hero is allegedly a Jew-killer. The country’s most popular online news outlets republished materials from a little-known portal of doubtful repute where a colorful social democrat from Šiauliai had smeared General Vėtra. Previously, this same individual had put the blame for the the deaths of Druskininkai Jews on the partisan leader Adolfas Ramanauskas-Vanagas.

Well this time the text made it rapidly into English for the outside world! The English version of Bogdanas’s effective defense of national policy of honoring Holocaust collaborators was published prominently in the Lithuania Tribune (which doubles nowadays as English Delfi.lt), without any contrary views following, leaving readers with the impression that anyone who thinks it is a bad idea for Holocaust perpetrators in Lithuania to be honored as national heroes must be a part of Putin’s anti-Lithuanian information war “aimed at pillars of the state” [!]. I can only thank Mr. Bogdanas for popularizing my articles, although I am a bit baffled at how articles that were written several years ago (long before the removal of the statues and the current post-Ukraine crisis “information war”) can now be used to argue that objections to the glorification of Holocaust collaborators are “Russian” or “Putinist” or “part of the information war.”

Delfi.lt columnist Dr. Kęstutis Girnius went on to expand (on 18 August 2015) on the topic of information warfare, opened by Bogdanas: “Some commentators are apt to maintain that accusations towards Kazys Škirpa and Jonas Noreika, prominent in the recent weeks, are part of the ‘information warfare’”. He mostly defends Škirpa, after whom a street is named in Vilnius and in Kaunas, and whose role in the Holocaust has somehow come under the purview of the Department of Cultural Heritage lately. Girnius admits that “Škirpa’s personality is controversial. Critics point at antisemitic sentiments in proclamations spread by Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF), which was led by him: proclamations announced the revocation of the right to settle, originally granted to Jews by the duke Vytautas Magnus.” But, according to Girnius, “the call to kill can only be found in a few proclamations, so it could have been supplemented by someone outside of the LAF. Škirpa did not take part in executions, nor did he encourage them.” So much for hapless apologetics par excellence.

Girnius only mentions Noreika once, at the very beginning of the article, and there might be a reason for this partial silence on the prime focus of the multilateral summertime debate. One of Noreika’s tasks during the June uprising was to distribute LAF proclamations (printed in Berlin) in Plungė. If Girnius were to admit this, he would have no one else to blame for supplementing the proclamations with a call to kill…

As the discussion got heated, Markas Zingeris, writer and director of Vilna Gaon State Jewish Museum, decided to step in (19 August 2015), naturally on Valatka’s side. He presents an interesting comparison:

A few weeks ago in Lüneburg, Germany, Oscar Groening was tried. A 94 year old man is accused of being an accomplice in killing 300,000 European Jews from various countries. […] Why was he tried? Simply for book-keeping the wealth acquired from Jews, for being a tiny cog in a monstrous genocidal machine. He was listing “the portable property” of Auschwitz victims. He counted the money that dropped from the pockets of Nazi victims. The court understood and the witnesses agreed: had these “cogs” been missing, the whole industry of the Holocaust would not have been possible.

He also deigns to offer a moral approach to Noreika’s justifiers: “It might very well appear that defenders of Noreika think the decree to stock and redistribute belongings of those on the death row – basically, marauders’ loot – can, in some way, be moral. The only thing that was important here was that the elimination of Jewish citizens would follow the plan.” Zingeris’ article is also interesting in that he was virtually the last one to join the discussion, so he could provide a review of all the other disputants.

But Markas Zingeris did not succeed in having the last word.

Arvydas Anušauskas, politician, member of parliament, a prime initiator of the legal campaign against Holocaust survivor, scholar and veteran of the anti-Nazi partisans Dr. Yitzhak Arad, member of the commission on Nazi and Soviet crimes, also had some thoughts on the issue (20 August 2015). One can see what a fine politician he is, energetically proceeding in his article to relate the discussion on Noreika with another scandalous story from a separate historical exhibition, when late president Algirdas Mykolas Brazauskas’ name was mentioned in the context of Soviet KGB and nomenclature. Charming. (The late president and then prime minister Algirdas Brazauskas is of course hated by the ultranationalist camp; in addition to honoring Noreika he also honored veterans of the anti-Nazi partisans and tried to tell more of the truth about the Holocaust.)

Anušauskas’s thoughts on Noreika:

We must state everything we know about Jonas Noreika “Generolas Vėtra” – captain and lawyer in the Lithuanian armed forces, prisoner of Stutthof concentration camp, chairman of the “Lithuanian National Council” resistance group – and we must base it on facts. He might not have been among the organizers of armed resistance in 1945-1946 (he only attempted to establish connections with the armed resistance squads), but it was nevertheless enough to get him sentenced and shot to death on February 16, 1947. He was also the Šiauliai county governor on the last days of Lithuanian provisional government. Is that a crucial fact? Not really, for he was the county governor afterwards, as well. […] To assign all tragedies in Šiauliai county to him is not just, especially basing this on distorted or invented facts. Is a county governor morally responsible for his compatriots being executed by Nazi occupation government? I think he is. Even if the information was not shared with him. News from the parishes would reach him sooner or later.

After this, Anušauskas, who is today a member of the state’s commission on Nazi and Soviet crimes, starts telling a story of Jacob Gens, police chief in Vilna ghetto, and encourages us all to stop polishing biographies. But he says nothing about public memorials to Nazi collaborators.

But we should talk about them. The discussion cannot be satisfactory without realizing how many and what massive signs of state-sponsored public-space adulation for these people there are in Lithuania.

For example, the Department of Cultural Heritage suggested renaming Škirpa Street in Kaunas, but somehow forgot about Škirpa Alley right near Gediminas Hill in Vilnius.

There is a suggestion to remove the memorial plaque from the wall of the Wroblewski Library, but a much more prominent accolade to Noreika on the wall of the Museum of Genocide Victims, on Gedimino Boulevard, a stone’s throw from our parliament, is not even mentioned. This was pointed out in Defending History’s own brief intervention this summer (20 August 2015) which was not part of the local debate but more an effort to spread the word about Gochin’s article in the Jerusalem Post (of the same date) which succeeded to bring the clear picture about the honoring of a Holocaust collaborator to the attention of an international English-language readership. Gochin is the author of a recent book that includes a section on Noreika’s participation in the Holocaust and the current state-sponsored honors for the man across our land. Then (on 29 July) S. Kanovičius (Kanovich) followed up with his own cogent article in English in i24, highlighting for an international audience the issue of state-sponsored glorification of Holocaust perpetrators in Lithuania. But while the issue was being made clear to foreign readerships by both authors, the local debate, in Lithuanian, has been sinking into further obfuscation.

How about memorial plaques of Noreika in Kaunas district of Panemunė (Vaidoto 209) and Šiauliai (on Vilnius Street, on the former county administration building, where the Šiauliai district municipality is now based)? How about other Noreika Streets in Kaunas district of Aleksotas, Narsiečiai and Šukioniai in the Pakruojis district, the aforementioned school named after him, and a monument in Šukioniai? Will the authorities only remove one memorial (a plaque on a library) and leave the street names, the stone shrine outside the Genocide Museum and the others?

Or, perhaps, will they even produce more of them, in order to “win the information warfare” not against “Putin and Russia” but against the simple truth about the Holocaust in Lithuania?

So far, the answers to these questions remain unknown.