O P I N I O N

by Milan Chersonski

Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij), longtime editor (1999-2011) of Jerusalem of Lithuania, quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania, was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania, which in Soviet times was the USSR’s only Yiddish amateur theater company. The views he expresses in DefendingHistory are his own. This is an authorized translation from the Russian original.

Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij), longtime editor (1999-2011) of Jerusalem of Lithuania, quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania, was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania, which in Soviet times was the USSR’s only Yiddish amateur theater company. The views he expresses in DefendingHistory are his own. This is an authorized translation from the Russian original.

Photo: Milan Chersonski at this desk at the Jewish Community of Lithuania (image © 2012 Jurgita Kunigiškytė). Milan Chersonski section.

Can you imagine a European Union / NATO government investing millions in setting up a “Peace Park” in its beautiful capital city, in memory of people buried at the site of the park, when hundreds of them were Nazi collaborators who eagerly supported the annihilation of the Jewish population of their country?

Earlier this month, VilNews.com prominently published an article by Vincas Karnila, presented as the Introduction to a series called “The Mass Graves in Tuskulėnai.” It is a panegyric to the employees of the Museum of Genocide in Vilnius and the Center for the Study of Genocide and Resistance for their tireless efforts to establish the Tuskulėnai Peace Park. Readers are informed that six articles will follow. [Update: Subsequent articles in Karnila’s series can be found in www.VilNews.com.]

We know from official sources that Soviet KGB victims were buried at Tuskulėnai from 1944 to 1947.

Karnila tells us:

“I hope the information we share with you will provide some insight into the tragic events that took place at the KGB prison and Tuskulėnai during the Soviet occupation of Lithuania. I also hope it will give you some idea of how much effort many people have had to make to this day to honor the victims and try to bring some comfort to their families and friends. I strongly hope that the history we are discussing will bring us information which is still unknown.”

So we shall wait for Vincas Karnila’s six articles. In the meantime, we will react to the first, by outlining what is known about “Tuskulėnai Peace Park,” a major new tourist attraction in today’s Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania.

◊

For several decades after the war there were rumors that the Tuskulėnai (Tuskuleny) area located in the Žirmunai district of Vilnius, across from the Church of Saints Peter and Paul on the opposite bank of the Neris River, was home to a secret facility.

Increased interest in the park and buildings there, which had been a private estate in the early twentieth century, began in 1990-1991 when the government of independent Lithuania took possession of secret documents indicating that people shot in the basement of the KGB building at Gedimino Prospect No. 40 in Vilnius from 1944 to 1947 were buried at Tuskulėnai.

In early 1994 Tuskulėnai was excavated and human remains were discovered. On 25 January 1994, a state commission was established by Lithuanian presidential decree 216, and on 4 July of that year the exhumation of remains began. According to documents from the State Security Department of Lithuania 780 people were buried there. In the eight years leading up to 2002, archaeologists located the remains of 706 people.

On 2 February 1998, the Lithuanian government formed a commission to commemorate the Tuskulėnai victims. Under the proposal made by the commission, the Lithuanian government adopted resolutions 932 of 19 June 2002, and 322 of 28 March 2007, in which a program for establishing the Tuskulėnai Peace Park was approved.

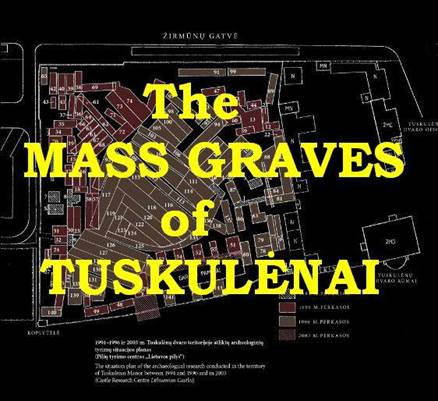

Section of the new “Peace Park” in Vilnius

It took more than ten years to set up the Tuskulėnai Peace Park. On 28 September 2011, the park officially opened to the public. To visit Tuskulėnai Peace Park, one must call during working hours in advance and register as a visitor, and duly be recorded on the list of visitors.

The main elements of Tuskulėnai Peace Park are the manor building and the chapel-mausoleum, where, as stated in the government’s decree, “victims of the NKVD-KGB repressions of the years 1944-1947 are buried.” Shot at the KGB building at Gedimino Prospect 40 in Vilnius, they were later buried in Tuskulėnai.

There are ample professionally landscaped grounds.

◊

When modern historians write about Lithuanian resistance from 1941 to 1953, the concept needs to be treated with caution. Official Lithuanian historiography does not make a clear distinction between participants in resistance and those involved in acts of terror against the civilian population under the guise of being members of the resistance. Therefore evidence that someone was at the KGB prison in that period cannot be regarded as evidence that this person was definitively a participant in the struggle for Lithuanian independence, rather than a terrorist and murderer of innocent civilians.

People who participated in World War II ended up in the NKGB-KGB prison in different ways. Some participated only in the six-day “uprising” in Lithuania (from June 23rd to 28th 1941), taking control of strategic sites and property abandoned by the Soviet army and administration. Some gave up their weapons and went home. Many, following directives from the Lithuanian Activist Front, considered all Jews to be Communists and started plundering, raping and murdering them from the very first hours of the “revolt.”

Around 20,000 volunteers had voluntarily served in Nazi units in Lithuania by the end of the war in so-called battalions of national labor defense. They guarded ghettos and concentration camps, escorted Jews to the murder sites (mostly shootings pits), did much of the actual murdering, took part in punitive operations against civilians, and were exported to Nazi facilities outside Lithuania as well. When the Nazis retreated from Lithuania, a significant number of well-armed police, equipped by the Nazis, the so-called “Forest Brothers,” went into the woods. They terrorized the local population and killed innocent people who did not resist Soviet authorities.

◊

The historians of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Resistance studied documents found in the Special Archive (the former KGB archive) and offered the following statistics of the people shot in the KGB building:

● 43 participants in the 1941 rebellion (the so-called “white arm-banders”).

● 8 criminals.

● 257 participants in the genocide of the Jews.

● 77 who served in the Nazi security police.

● 32 soldiers of the Polish Armia Krajowa (“Home Army” of the Polish wartime resistance).

● 157 Red Army deserters, members of Lithuanian resistance, and political prisoners.

● 1 chief military commander of the occupational Nazi army in Lithuania, who gave orders for the mass murder of Jews.

The Genocide Center’s English website omits all information on the fascists, Nazi collaborators and local Holocaust perpetrators who were buried at the site. A similar whitewash appears on the tourism site for the Vilnius municipality.

The ethnicities of those shot were also published: 559 Lithuanians, 56 Russians, 52 Poles, 38 Germans, 32 Belorussians, 18 Latvians, 9 Ukrainians, 3 Jews, 1 Estonian, 1 Uzbek, 1 Tatar, 1 Ossetian, 1 Chuvash and 1 Udmurt.

Remains found at Tuskulėnai were to be housed temporarily by the Catholic Church, but the church refused to accept the remains even for temporary storage, on the grounds that those executed were not all Catholics.

The pits at Tuskulėnai for burying those killed were dug beforehand and some pits were used repeatedly. In such cases, first lime and then diesel fuel were poured over the victims’ corpses, and roofing felt was then placed on top. The corpses of subsequent victims were thrown on top of the layer of roofing felt. Tuskulėnai was used as a burial site until the spring of 1947, when a 26 May 1947 decree by the Supreme Soviet substituted a 25-year prison sentence for the death penalty.

◊

Dalia Kuodytė, the former director general of Lithuania’s Research Center for Genocide and Resistance, now a member of the Lithuanian parliament, had herself opposed the plan to turn the grave site into a memorial. She apparently had good reason to believe that among those executed in the KGB cellars were many murderers of Jews as well as people who terrorized local populations. She warned MPs and Government ministers:

“By erecting a memorial to them we will encounter protests by the world Jewish community.”

But then Deputy Minister of Culture Ina Marčiulionytė objected to that consideration, contending that “all are equal in the face of death.”

Shimon Alperovich, chairman of the Lithuanian Jewish Community (LJC) said it was not the first time he had heard such horrible statements from government officials. In his opinion,

“The creation of Tuskulėnai Memorial Park means paying tribute not only to resistance participants, but to the executioners who were justly punished for their direct participation in the extermination of the Jews in Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. This kind of attitude towards the memory of genocide victims can be found in no other country which experienced Nazi occupation, neither can it be found in Germany.”

Despite these protests, Lithuania’s current leaders have decided to preserve and honor officially the memory of those murdered in the KGB basement, without regard to what they did. In 2002 Severinas Vaitekus published a monograph called Tuskulėnai: Execution Victims and Executioners (1944-1947) [Tuskulėnai: egzekucijų aukos ir budeliai. 1944-1947]. A cell used for the shootings is now an exhibit in the Genocide Museum.

◊

The idea of commemorating the persons buried at Tuskulėnai, the so-called Forest Brothers, was actively promoted by Lithuanian MP Antanas Napoleonas Stasiškis. On 12 September 2000, he, along with 47 other MPs (there were three abstentions and 90 MPs absent) pushed through a law under which the pro-Nazi declaration of the Lithuanian Provisional Government’s “Declaration of the Restoration of Independence” of 23 June 1941, was recognized as a legitimate legal act by the Republic of Lithuania. Thus, thanks to A. Stasiškis and his cohorts, Lithuania assumed moral responsibility for the pro-Nazi actions of the Lithuanian Provisional Government.

Under the pressure of protests by Lithuanian public organizations and world public opinion, the then Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus declined to sign this act into law, but it was not and has never been repealed. Instead, the parliament declared the law “adopted [for further consideration] on the first reading.” Thus the Lithuanian parliament still has the opportunity to return to this issue and finally adopt (or reject) the bill on a second or third reading.

A. Stasiškis went on to take revenge for the foiling of his attempt to legitimize the Provisional Government two years later, in 2002. He said confidently then: “The government will endeavor to perpetuate historic memory at Tuskulėnai.” And that is precisely what they went on to do.

Here is the opinion of a competent person on whence and whither, in both cases, the “wind was blowing in the sails” of Stasiškis’s career. On 24 August, 2011, the website http://www.politikosaktualijos.lt published an article by former resistor and dissident Juozas Ivanauskas called “The Spirit of Tartuffe in our History,” in which he asserted that the “dissident” Antanas Stasiškis “did not demonstrate his worth practically in any clandestine activities, he followed all of Vytautas Landsbergis’s instructions implicitly, and hardly by accident later became one of Landsbergis’s closest associates. For example, Antanas Stasiškis fulfilled Vytautas Landsbergis’s instruction to squeeze the real dissident Vytautas Skuodis out of the post of director of the Genocide and Resistance Center.”

Ivanauskas wrote:

“That’s why we, unfortunately, have no real history of resistance in Lithuania, because the archives were looted and destroyed, and the cases were stolen.” [emphasis added]

◊

With new parliamentary elections now approaching and the standing of the Homeland Union and Lithuanian Christian Democrats coalition extremely low, a tried-and-true recipe for cheering up the coalition’s disappointed electoral base is to stir up interest on the issue of demanding compensation from Russia for the oppression of 1940-1941 and the 1944-1953 period. Another foolproof way to strengthen and unite this electoral base is the stirring up of pseudo-patriotic feelings by manipulating public opinion regarding the graves of Soviet soldiers who died fighting for the liberation of Lithuania from Nazi occupation. But they must hurry. There are, after all, only about two months left to go before the election!

MEP Vytautas Landsbergis, formerly the chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania and formerly the head of the Homeland Union/Conservative Party, took up the case. He showed a sudden interest in the graves of Soviet soldiers, and offered to have the remains of Soviet soldiers (who in fact gave their lives for the liberation of the resort town Palanga from Nazi rule) dug up from their cemetery and removed from the city center to somewhere out of sight. “If it is agreed that Palanga city authorities are now working well, I do not understand why they have not taken care of the graves yet,” the MEP said with a measurable modicum of irony.

The attempt to move the soldiers’ graves and the monument in their memory to somewhere out of sight is not merely an expression of contempt for the people who gave their lives to liberate Lithuania from the Nazi occupation.

The desecration of the graves of Red Army soldiers who fought against Hitler has proven to be, over two decades of Lithuanian independence a pre-election gambit that successfully rallies that certain electoral base in the struggle for seats in next session’s parliament.

Still, the most reliable method to rally voters — and it, too, has proven itself to be effective — is to seize control of Lithuania’s historic memory. The history of the country and its people is built not through a rigorous and comprehensive study of historical records and documents, but through making it up, and misrepresenting the wishful as real.

RELATED:

- Articles by Milan Chersonski

- The Genocide Museum

- The Genocide Center

- State honors for 1941 collaborators

- State honors for the 1941 Nazi puppet prime minister

- Section on glorification of collaborators in Eastern Europe

- Dark tourism