OPINION | VILNIUS JEWISH LIFE | LITVAK AFFAIRS | HUMAN RIGHTS

◊

by Dovid Katz

◊

VILNIUS—Rabbi Sholom Ber Krinsky, Vilnius’s Chabad rabbi, has served Jewish people here and the city’s diverse cultural mosaic for some twenty-two years. And sure, he has had his share of issues, run-ins and errors over the decades, just like everyone else in town. His numerous packed Jewish holiday celebrations have become part and parcel of the city’s remarkable twenty-first century Jewish footprint, most famously on Chanukah. But yet again, he was denied entry to the Jewish community building for daily prayer services this morning by the burly security guards at the official Jewish Community building, who seemed highly adept at avoiding frontal photography. Services were abruptly moved there on Friday evening because of a mysterious “plumbing problem” (heating, in some versions) at the city’s Choral Synagogue. Then, on Friday evening 28 October, police were called to evict from the makeshift prayer address Rabbi Krinsky and his children, pupils and co-worshippers (reports by R. Bloshtein, Z. Olickij, and J. Piliansky). A sad date in the modern history of Jewish Vilnius.

Observers have been stunned because, unlike situations over a decade ago when there were serious synagogue disputes and disruptions of arguable vintage, the decision, just over a year ago, for the two prayer groups (minyónim, Israeli minyaním) to pray together in the main synagogue building — the Choral Synagogue at Pylimo Street 39 — has led to a delightfully harmonious service every day for just over a year now, and this following over a decade of peace between the two groups (the one recent exception, on a weekday, being part of the current series of events, when the then gabbai [Yiddish gábe] or synagogue administrator was dismissed after asking Rabbi Krinsky to blow the shofar on a day when no other rabbi was present). Indeed many of the “official worshippers” (who receive a stipend) at the main synagogue are themselves frequent participants also in Rabbi Krinsky’s Sabbath meals and other events, with no ill will or harm to any party. Disturbingly some have reported being warned that they would lose their stipends if caught attending any of Rabbi Krinsky’s events at Chabad House.

Moreover, there has been complete agreement by all sides, including Rabbi Krinsky and his congregation, that in the main synagogue all public prayers and rites are conducted strictly according to the Lithuanian Misnagdic rite, not the Chabad rite (which differs slightly, but for traditionally religious worshippers in both traditions, very significantly).

SEE UPDATES

One of the best examples of the harmony came a few months ago, when Sabbath fell on the yórtsayt (death anniversary) of Rabbi Krinsky’s late dear mother. The official rabbi, Rabbi Samson Daniel Izakson, and the universally beloved cantor Shmuel Yusem, graciously arranged for Krinsky to lead the main Sabbath morning prayers, and say Kaddish as per Jewish tradition for a worshipper’s yórtsayt. Rabbi Krinsky adhered aloud to the exact same Misnagdic (more exactly: Núsakh Ashkenaz) rite as the official rabbi and cantor, reading from the same prayerbook on the bimah (he naturally follows the Chabad rite when he leads prayers at Chabad House). It was a show of Jewish harmony in Vilnius that was regarded by regular worshippers as a symbolic milestone in the successful growth of the synagogue under the leadership of the official religious community, itself under the auspices of the official Jewish community. Much credit on the day was accorded the official head of the religious community, Simas Levinas, who had publicly announced on the Sabbath morning last winter when the new official full-time resident rabbi, Rabbi Shimshon Daniel Izakson, was introduced, that he and Rabbi Krinsky would both be giving their sermons and participating together in an atmosphere of inclusiveness and unity. There is also a second official rabbi who comes periodically from Riga, Rabbi Kalev Krelen.

There are in a sense two sets of issues, one practical and one ethical. On the practical side, the synagogue had been failing for years now, at least in appearance, to attract sufficient numbers of people beyond the “subsidized mínyen” even on Friday evenings and Sabbath mornings, to give the place the ambience of a genuine vibrant congregation. Once the merger was agreed last year, and all the wishing-to-pray Jews of Vilnius started to come to the same synagogue — the historic Choral Synagogue — the numbers doubled, the women’s prayer balcony (Ezras Nóshim) was no longer empty, and guests from around the world were impressed at the dramatic growth of prayer services, notwithstanding the demographic challenges faced by the Jewish community. They were also impressed by the harmony achieved.

On the ethical side, there is the phalanx of human rights issues raised by intra-community intolerance that reflects poorly not only on the official leadership of the community, but on all of the Jewish community in Lithuania, now numbering under three thousand (despite various spin-maestros’ inflation), and by extension, on all the minorities in the country who, as in any country, have human rights issues to air from time to time. There has been considerable concern that the chairperson has over a few short years managed to deprive the community of its beloved long-serving young executive director, Simon Gurevich (Simonas Gurevicius), who was inexplicably dismissed in 2015 during a wave of “Lithuaniazation” by which a de facto policy took hold of considering local Jews unfit for the “good jobs,” with, it seemed, replacement by ethnic Lithuanians in what is the Jewish community (imagine an African-American Community Center in the USA where the drive is toward lily-white appointments throughout). One of the most stupendous wastes of funds has concerned the PR-based “Bagel” project, representing the interests of certain elements in the Lithuanian government much more than those of the small number of living local Jews who are the bona fide Jewish community here. The eminent chief rabbi of eleven years, Rabbi Chaim Burshtein was also dismissed in 2015 after he declared that he would adhere to the unanimous rulings of all the world’s great Litvak, Misnagdic rabbis in opposing the new congress center project on top of the old Vilna Jewish cemetery. In fact, local dark humor had it, that after dismissing Rabbi Burshtein, a search was on specifically for so-called “Litvak rabbis” who would support, not the integrity of five hundred years worth of Vilna Jewish families paying for their loved ones’ graves, but the business and political interests determined to have the new national congress center where revelers would clap, cheer, sing and urinate over those graves. The signs so far have been ominous, even though such luminous Litvak scholars as the Be’eyr HaGóylo (Be’er HaGolah), the Chayei Ódom (Chayei Adam) and the Rashásh are still buried there, something that touches any bona fide Lítvishe neshóme (Litvak soul). On a lighter note, the ever-active Vilna Jewish humor circuit produced another quip: “They are looking for new rabbis who will be not the AntiChrist but the AntiKrinsky.”

These disturbing events serve as backdrop to this week’s efforts to banish and delegitimize yet another Vilnius Jewish figure, Rabbi Krinsky. The movement to “Lithuanianize” the Jewish community may be molding it into a PR fantasy playground for government manipulation and the fiefdom of a handful of well-heeled compliant Jewish elites. At times, that rarefied group seems lately to include perhaps only the chairperson (in professional life the nation’s top EU citizenship lawyer for foreigners and a widely admired brilliant attorney) as the one ostensible “real Litvak in the world.” The communidrama is causing growing damage and disquiet, and making for not a little dark Litvak humor among the increasing number of local Jews who no longer feel comfortable even entering their own community center (they are warmly welcomed when visiting just about any church in town). It was announced last year that the (of course, non-Jewish) head of the Jewish restitution foundation that disburses funds deriving from the religious Jewish property of Lithuania’s murdered Jews has married (wishing the new couple only mázltof and all the very best in the world!) the prime minister’s assistant for Jewish affairs who played a key role in the “rabbinic permission” to desecrate that same 500+ plus year old Jewish cemetery for the profits to come from the congress center (the “permission” came from a London Satmar Hasidic affiliated group in some opinions exposed, in the Jerusalem Post and JTA, for offering permissions, effectively, for hefty sums of money). The disturbing trend of a city full of “Jewish institutions” that avoid Jews appointees (when there still are Jews) has been the subject of comment more than once. But the official Jewish Community itself? But there has been an even weirder twist in recent months: Those Jewish-culture focused institutions that have become safe haven to a healthy diversity of Jewish views and people, are themselves under threat from the same campaign of exclusion and delegitimization disturbingly emanating from the “official Jewish community.”

◊

Of course anyone who disturbs a prayer service, or who rejects the rite established by a given synagogue can be barred legitimately. But this was not the case. Two Defending History correspondents were on hand throughout the long Simchas Torah service on the morning and afternoon of Tuesday, 25 October 2016. The Litvish Ashkenazic rite was adhered to meticulously and without the slightest objection from anyone. In fact, such things have not been on anyone’s mind as this has not been challenged for over a decade. Moreover, it was a beautiful service, at which both rabbis on hand, Shimshon Daniel Izakson and Sholom Ber Krinsky, gave their own excellent short sermons as always, offering the assembled a double dose of delightful Jewish festival enlightenment. Both interacted freely with everybody present. What happened from “Tuesday” the 25th of October and its successful Simchas Torah service, to “Friday” the 28th of October, when security guards and the police ejected from services (that had been moved because of “plumbing” or “heating” to the community center) Rabbi Krinsky and his pupils and children?

Internationally, on the religious side of things, while truly religiously observant Misnagdic Litvaks (before the war the vast majority of religious Litvaks) and Chabad (the great survivor group of Lithuanian Hasidism), continue to adhere to their own, slightly differing rites, there has been pan-Litvak religious peace and harmony in the Lithuanian lands since the earlier nineteenth century. Back in 1843, Isaac of Valózhin (Reb Ítsale Valózhiner), the spiritual head of Misnagdic Litvaks, traveled in the same wagon with the then Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (der Tsémakh Tsédek) to plead with the authorities in St. Petersburg to abandon their plans for forced “modernization” as demanded by Haskalah proponents. Nearly all the Lithuanian shtetls around Vilna had their (minority, to be sure) Chabad prayerhouse alongside the dominant Misnagdic prayerhouses (though in a handful of cases, famously Rákishok, now Rokiškis, there may have been a Chabad majority among the Jewish population). Come to think of it, Marc Chagall was from a Chabad family, so are we going to delete him from the celebrated pantheon of Litvak artists and the various fine books on Litvak art published in Lithuania?

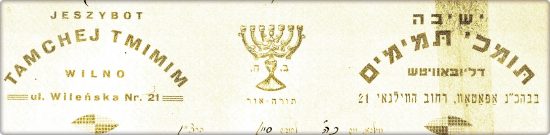

Letterhead (dated 15 June 1936) of the famous Chabad Lubavitch Yeshiva (a branch of Téymkhey Tmímim [Tomechei Temimim]), in Opatov’s Synagogue at Vilna Street 21 (Vilniaus gatvė today in Vilnius; the building did not survive). In Vilna Yiddish folklore, the preeminent humorist Motke Chabad often plays tricks on the wealthy magnate Opatov himself. From September 1939 onward, Vilna’s Lubavitch yeshiva played precisely the same role as the other yeshivas in Lithuania: establishing for yeshiva scholars and students from Nazi occupied Poland a path to escape in the hope of saving their lives. Photo credit: Leyzer Ran, Jerusalem of Lithuania, New York 1974, vol. II, p. 294. By permission of Faye Ran (NY).

For Jews in Vilnius, it was shocking to read on the official website of the Jewish community a botched description of Chabad Judaism by a Lithuanian scholar who is occasionally rolled out at government conferences on “the Jews” and may not realize how, on this occasion, she has been manipulated to sow discord where there is none. By stressing episodes that defame one group of Litvaks (all long-time groups on the planet have their historic dark spots), she has been weaponized as part of an effort to exclude part of the congregation from prayers. Would she have any part of that kind of endeavor in her own religious denomination?

The formal head of the Religious Community, Simas Levinas, is one of the most admired people in the Jewish community. He was on hand throughout the harmonious hours-long holiday service on the Tuesday. Again: What happened between The Tuesday and The Friday? His many wellwishers await a rapid clarification of some very sad and self-inflicted blows of recent days that represent a setback for the wider Jewish small-c community, in Vilnius and far beyond. As more than one local person has put it, calling the police to evict most of the people who come to pray voluntarily (without receiving stipends) is no way to build a religious community. Has the plumbing (or heating) been fixed yet? The decimated, remnant tribe of Litvak Jewry in the once-upon-a-time Jerusalem of Lithuania deserves better. Much better.

◊

The author, a staunch Misnaged, is at work on his book Vilna Jewish Culture to complement his earlier Lithuanian Jewish Culture (revised edition Baltos Lankos 2010). His website lists a number of his writings on Litvak Jewry. The shorter Seven Kingdoms of the Litvaks (Vilnius 2009), published by Lithuania’s Ministry of Culture, is available gratis online, as is his Yiddish book Tales of the Misnagdim of Vilna Province. He is currently translating the Bible into Lithuanian Yiddish. Some of his Yiddish short stories, focused on the Misnagdic tradition of old Jewish Lithuania, have appeared in translated anthologies in English, German, and Italian (with Russian versions in progress and individual stories appearing also in Lithuanian). His map of the Litvak lands was featured in 2015 on the banner of the Lithuanian Jewish Community’s website.

◊

SEE UPDATES