O P I N I O N

by Geoff Vasil

And the Lord God said unto the woman, What is this that thou hast done? And the woman said, The serpent beguiled me, and I did eat. Genesis 3:13

And he said, What hast thou done? the voice of thy brother’s blood crieth unto me from the ground. Genesis 4:10

Driving east out of Rokiškis, fields give way to forest, and the lake country leads on to strange and wild hills in an abandoned quarter of the country bordering Latvia. The lake country is beautiful, almost alpine in its effect, and spotted with small settlements and villages of varying sizes, some even boasting gas stations and schools.

It is here, outside Rokiškis (Rákishok in Yiddish) towards the east, that we join the story, in a village called Obeliai by the Lithuanians, and Abel by the Jews, once upon a time. There is no “right way” to say the name, it is odd in both Lithuanian and Yiddish, and perhaps hails back to some Latvian dialect rather than a Lithuanian one, although the general sense is “apples” in the Baltic languages.

See also

Evaldas Balčiūnas on the Obeliai monument

The Lithuanians of Rokiškis and the neighboring lake district to the east joined in to help the cause of the Holocaust early, even before the Germans arrived, according to eye-witnesses with whom I’ve spoken. While the Lithuanian Nazis set up a holding-pen for Jewish men in Rokiškis proper, other members of the LAF (Lithuanian Activist Front) in the lake district acted autonomously and began murdering Jews almost immediately, leaving the corpses of men, women and children in ditches along the rutted roads.

Abel, which was perhaps half Jewish by population, perhaps a bit more at times, had its share of Nazi collaborators as well, and not all of them were ethnic Lithuanians. One of these non-Lithuanian Lithuanian Nazis was named Guriy Kateshchenko. He was one of what are called Old Believers, a sect of Russian Orthodox who fled Russia after reforms effected several centuries ago, many of whom settled in Lithuania, traditionally a tolerant land willing to accept political and religious refugees. His name, Guriy, reflects this fly-in-amber quality of the ethnic minorities in Lithuania; in modern Russian it would have been the familiar Yuri.

Guriy wasn’t from Abel, but fell in with a group of Lithuanian Nazis already operating there. They weren’t simply misguided youths or misdirected Lithuanian patriots who fell for the Third Reich’s propaganda; they were actively harboring and aiding Nazi infiltrators who had parachuted in at least several weeks before the outbreak of Soviet-Nazi hostilities, and were sending detailed information back to Berlin. The LAF underground cells in Lithuania, Lithuanian Nazis essentially, were planning to act as soon as the Nazis crossed the Soviet border, and had secured weapons for that purpose, and were basically in control of the railroad throughout Lithuania. In Abel they had no problem finding weapons, and the LAF set up a machine-gun nest in the belfry of Abel’s only church, with the knowledge if not blessing of the priest there, to fire at the backs of the Red Army.

The history of the Holocaust of Rákishok, Abel and surrounding towns and villages is too involved to treat fairly in a short article, so we skip ahead to early 1942, when Guriy Kateshchenko, ensconced in a railroad job as was his brother Ivan in Abel, comes up with the idea of building a monument to six fallen Lithuanian Nazi martyrs, six LAF members who died in some manner or other as the local LAF was firing on retreating Soviet troops, and rounding up and murdering Jews.

The fact of the matter is that the Kateshchenko brothers did design and build a small monument to fallen Lithuanian Nazis in early 1942. After the war the Soviet authorities decided it should be destroyed, but never got around to actually tearing it down. Over the decades it was vandalized and used as a source of construction materials, until it finally became such an eye-sore that local schoolchildren were told to take care of it during the day that used to be allotted in the Soviet Union for communal “volunteer” work, things such as picking up trash in parks, cutting weeds and so on, back in the 1980s. It wasn’t really voluntary, it was compulsory, but citizens usually pitched in cheerfully since there wasn’t any choice and the subjects of the talka were usually directly beneficial to the local community.

Controversy has only come up recently over the long-forgotten Nazi memorial because local activists in Abel and other Nazi apologists in the Lithuanian Center for the Study of the Resistance and Genocide of Residents of Lithuania have been trying to resurrect the monument in Abel. “Genocide” has even coughed up a large chunk of state money for the project. Defending History has reported on the project before, most recently in the piece by Evaldas Balčiūnas, where he points out that the original monument was almost certainly funded by property taken from local Jews after they were murdered. Without dwelling on that point too much, it is worthwhile noting a real conflict existed between the German and Lithuanian Nazis over how to divide up the loot, the Germans claiming it for themselves, while the Lithuanians had, in many cases, “got there first.” A scheme to “re-invest” some of it in, ostensibly, a public works project, would have provided an opportunity for the classic construction industry kickback scam, although there are no records available to confirm that took place.

Instead, the proponents of the plan to resurrect the Nazi shrine in northeastern Lithuania make much of the supposed selfless sacrifice during war time to honor fallen Lithuanian freedom fighters by comrades who paid for it out-of-pocket. They deny its tie to the Nazis completely and attempt to situate the object in an historical vacuum, evidently believing the white-washed version of history they’ve been fed which holds Lithuanian Nazis were not Nazis, at least not in a bad way, and fought to save their country from invasion from all sides.

Not only were Lithuanian Nazis really Nazis, in a bad way, and NOT interested in stopping the invasion and occupation of their country, but the monument in Abel was conceived and built in emulation of similar monuments set up by the Third Reich in Germany.

◊

The Nazi 9/11

The monument in Abel is part and parcel of a push by the Nazis to create a new tradition, cult, some would even say religion, of commemorating Nazi martyrs. When one hears the Nazis and the events of September 11, 2001, mentioned in the same breath, it’s usually in reference to the Reichstag fire as the pretext for Hitler’s seizure of total power through so-called anti-terrorism enabling legislation, but there is a more literal connection that bears on the issue at hand.

Many people know about the Horst Wessel song that was Nazi Germany’s alternative official national anthem, complementing the better-known “Deutschland über alles.” A fewer number know who Horst Wessel was, why he was so important to the Nazis in their drive for domination, and the cult of blood represented so aptly in rituals surrounding what was called the blood-flag.

Wessel was adopted as a martyr by the early Nazis, although it’s unclear whether he really died for political reasons at all. He wrote songs and poetry, and the Nazis back in their early career set his final song, his swan-song as they used to say, to music, and used the arrangement to reinforce morale. When Hitler was appointed chancellor in 1930, the Horst Wessel song was sung by delirious storm troopers who marched by torchlight throughout the night in Berlin.

Wessel was parlayed into a legend by Reich propaganda minister Goebbels and became a hero and role model for youth. He was killed in February of 1930, seven years after the seminal event in the Nazi cult—or religion—of martyrdom. Here’s how William Shirer, the American reported stationed in Berlin who was an eye-witness to the rise of the Third Reich, although not this particular event, describes it:

About a quarter to nine on the evening of November 8, 1923, after Kahr [the state commissioner of Bavaria] had been speaking for half an hour to some three thousand thirsty burghers, seated at rough-hewn tables and quaffing their beer out of stone mugs in the Bavarian fashion, S.A. troops surrounded the Buergerbräukeller and Hitler pushed forward into the hall. While some of his men were mounting a machine gun in the entrance, Hitler jumped on a table and to attract attention fired a revolver shot toward the ceiling. Kahr paused in his discourse. The audience turned to see what was the cause of the disturbance. Hitler, with the help of Hess and of Ulrich Graf, the former butcher, amateur wrestler and brawler and now the leader’s bodyguard, made his way to the platform. A police major tried to stop him, but Hitler pointed his pistol at him and pushed on. Kahr, according to one eyewitness, had now become ‘pale and confused.’ He stepped back from the rostrum and Hitler took his place.

‘The National Revolution has begun!’ Hitler shouted. ‘This building is occupied by six hundred heavily armed men. No one may leave the hall. Unless there is immediate quiet, I shall have a machine gun posted in the gallery. The Bavarian and Reich governments have been removed and a provisional national government formed. The barracks of the Reichswehr and police are occupied. The Army and the police are marching on the city under the swastika banner.’

This last was false; it was pure bluff. But in the confusion no one knew for sure. Hitler’s revolver was real. It had gone off. The storm troopers and their rifles and machine guns were real. Hitler now ordered Kahr, Lossow and Seisser [the Bavarian state commissioner, the commander of the Reichswehr in Bavaria and the head of the state police, respectively, forming the triumvirate ruling Bavaria at that time] to follow him to a nearby private room off stage. Prodded by storm troopers, the three highest officials of Bavaria did Hitler’s bidding while the crown looked on in amazement.

After pointing a gun at the three and trying, and failing, to get them to join his new provisional government, Hitler left them locked up and told the audience in the beer hall they had come over to his side, but escaped as soon as they were able, and Hitler’s declaration remained just that, neither Munich nor Bavaria were taken over by the Nazis and the coup failed. Rather than give up, though, Hitler marched the three-thousand storm troopers at his command from the beer hall towards the center of Munich on the morning of November 9, 1923, which was anniversary of the proclamation of the German Republic, following closely on what was German Veterans’ Day on November 4. Goering, Röhm, Hess, even Julius Streicher—all of whose names have come infamous to history—were there that day. The police were having none of it, despite Hitler’s wild shouts, “Surrender! Surrender!” Someone fired a weapon and the police began mowing down the largely symbolic fighting force. Those who didn’t flee clung to the pavement stones for dear life, according to Shirer. Hitler ducked so quickly he dislocated his shoulder, and was the first to get back up and run away, according to eye-witnesses. Sixteen Nazis died from gun shots and so did four police. Göring and Hess fled to Austria and the rest were arrested.

Someone managed to recover a swastika banner dropped by the marchers and covered in the blood of one or more of the dead. This became known in the Third Reich as the Blutfahne, or Blood-Flag, which the Nazis imbued with mystical powers and used to consecrate every “official” Nazi swastika flag.

As soon as Hitler and the Nazis came to power in Berlin, they made the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch a national holiday. They called it “die Neunte Elfte,” or “the ninth of the eleventh,” meaning, the ninth day of the eleventh month.

Here’s a passage from wikipedia under the entry for Beer Hall Putsch:

‘Die Neunte Elfte’ (the ‘Ninth of the Eleventh’) became one of the most important dates on the Nazi calendar, especially following the seizure of power in 1933. Annually until the fall of Nazi Germany, the putsch would be commemorated nationwide, with the major events taking place in Munich. On the night of November 8, Hitler would address the Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters) in the Burgerbräukeller (after 1939, the Löwenbräu, in 1944, the Circus Krone Building), followed the next day by a re-enactment of the march through the streets of Munich. The event would climax with a ceremony recalling the 16 dead marchers on the Konigsplatz.

The anniversary could be a time of tension in Nazi Germany. The ceremony was cancelled in 1934, coming as it did after the so-called Night of the Long Knives. In 1938, it coincided with the Kristallnacht, and in 1939 with the attempted assassination of Hitler by Georg Elser. With the outbreak of war in 1939, security concerns caused the re-enactment of the march to be suspended. It was never resumed. However, Hitler continued to deliver his 8 November speech through 1943. In 1944, Hitler skipped the event and Heinrich Himmler spoke in his place. As the war went on, residents of Munich came increasingly to dread the approach of the anniversary, concerned that the presence of the top Nazi leaders in their city would act as a magnet for Allied bombers.

Every Gau (administrative region of Germany) was also expected to hold a small remembrance ceremony. As material given to propagandists said, the 16 fallen were the first losses and the ceremony was an occasion to commemorate everyone who had died for the movement.

On 9 November 1935, the dead were taken from their graves and to the Feldherrnhalle [the site of the shooting in 1923]. The SA and SS carried them down to the Königplatz, where two Ehrentempel (Honour Temples) had been constructed. In each of the structures eight of the martyrs were interred in a sarcophagus bearing their name.

The passage doesn’t quite do justice to the sheer scale of the event. So that no one might accidentally forget to commemorate the Nazi martyrs, loud speakers were set up on streets throughout Germany to broadcast the event live. Munich became a sea of torches sweeping down its broad (and narrow) streets with jack-boot clicks precisely coordinated so as to sound as a single monstrous footstep. The Nazi leaders participated in wreath-laying ceremonies, but this was nothing compared with the roll-call ceremony, where the Nazis “read out the names,” to throngs of soldiers and the public. The idea was that someone in the audience, spontaneously and anonymously, was supposed to answer the roll-call of dead names with “here!” The various events were solemn to the point of verging on the creepy with a real Halloween atmosphere, as if the dead might walk the earth again.

The roll-call and other ceremonies followed the motto at the earliest memorial to the blood martyrs, “Und ihr habt doch gesiegt!” which translates loosely, “And they won anyway!”, and the whole commemoration can be summed up as, “they fought, they died, they won,” as indeed the Nazis themselves summed it up. This is crucial to understanding the full propaganda effect of the spectacle. This goes much deeper than Hillary Rodham Clinton’s glib yet macabre “We came, we saw, he died.” To give credit where it’s due, the Nazis were quite ingenious here.

The Anglo-Austrian Jewish historian of Nazi Germany Richard Grunberger has pointed out the Ninth of the Eleventh ceremonies in Munich were actually a copy of and surrogate for the Easter procession in Jerusalem to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre through the Stations of the Cross, and calls this Nazi copying of Christian ritual “obvious.”

What might not be obvious at first glance is the holistic approach the Nazis were taking towards their ultimately nativistic revitalization movement to forge a reich that would last a thousand years over the course of just one decade, an holistic approach very well illustrated in their newly formed cult of the blood martyr dead. Grunberger is exactly right that this was a Passion play enacted on the streets of Munich, but it is much more than that. It is more than a Nazi innovation on Catholic Christianity, and more than a Nazi usurpation of same, because it includes pagan, millenarian and occult themes which have occupied Europeans for centuries up till almost the present day.

First, it was the successful synthesis of Nazi and Christian themes in a form acceptable to the Germans of the 1930s, creating a broader base of support for the Nazi regime. It fudged over the schism already present within Nazism between Christians and neo-pagans by Christianizing Ragnarok and Nazifying Calvary, Ragnarok being the pagan equivalent of Armageddon. Called Gotterdammerung in German, it comes from Norse myth and is supposed to be the final battle in this world in which the forces of good and the forces of evil completely annihilate one another, after which a new cosmos, or new world order if you prefer, is supposed to come into being. The Nazis put this “total war” of extinction, with the forces of light represented by the racially superior Aryans and darkness the Jews and assorted other “darker people,” the Nazis’ Holy War, into practice, and we know it by other names: World War II and Holocaust.

The idea of total sacrifice, of sacrificing one’s life for a higher cause, and achieving victory in death, is at once very Christian and very much at the core of the Nazis’ philosophy and strategy. This underlines the second way in which it was so much more than a mere compromise with Christianity and even more than syncretism combining Teutonic/Norse mythology and Christian beliefs. Remember the summation of the essence of the Ninth of the Eleventh rituals: they fought, they died and they won.

This goes back to an occult credo, or formula, current in Europe for several centuries before the Nazis appeared, and was known to their predecessors engaged in all manner of occultism in the Thule Society. Indeed it was even used during Hitler’s lifetime by his sworn enemy, Rudolf Steiner, founder of the Anthroposophy movement, and is still used by his followers today. It is this Latin phrase:

Ex Deo nascimur, in Jesu morimur, per Spiritus Sanctum reviviscimus.

It’s all first person plural:

Of/From God are we born, in Jesus we die, through the Holy Spirit we live again.

The formula is reported to have come from the grave of the legendary Christian Rosenkreutz, a secret mausoleum reportedly discovered by his followers, the original inner circle of Rosicrucians, about a century after his death. Some sources put “In Jesu morimur” on the lips of tortured Templars, or as their final utterance as they were being burned at the stake. This might be a later interpolation intended to give the Rosicrucians a Templar pedigree, but there are reasons to believe the phrase might have come from Templar contacts with some form of Oriental or Coptic Christianity, which in turn might have “re-encoded” a pre-Christian formula in terms acceptable to Christianity. It is perhaps topical at the current moment to recall that the original Rosicrucians, the Gold and Rosey Cross, gave rise both to the modern movement and an occult society called the Golden Dawn, in addition to numerous smaller cults such as Rudolph Steiner’s. While the Rosicrucians in America were largely a media creation before they became a real phenomenon, with rumors of white-togaed disciples inhabiting secret underground villages inside Mount Shasta in Northern California, European Rosicrucians were a fairly serious group which endured the vagaries of masonry, freemasonry, republicanism and other historical shifts right up until the advent of the Third Reich.

Another reason to assign a pre-Rosicrucian origin to the phrase is that it so well harmonizes with an early Christian heresy which might be called dispensationalist or millenarian, but according to whose eschatology God represents an aeon, Christ the following aeon and the Holy Spirit the final aeon. The Law of the Old Testament/Torah according to this school of thought was abrogated by Christ, whose second coming is to usher in the final and perfected age of the spirit. Aeon here carries more than the meaning of epoch and spills over in space, forming a sort of cosmos unto itself, or a distinct phase-change in the physical universe. This idea of the three ages fits in very well with the Nazis’ ideas of the coming ubermensch living in the new age of the spirit. In the Nazi version, however, the age of the spirit isn’t bestowed from above, but is won in blood in the final apocalyptic struggle, Ragnorak, Armageddon or something akin to battle in the Bhagavad Gita, for which Catholic occultist Himmler displayed a distinct preference at times.

Aleister Crowley, the infamous Golden Dawn occultist who occasionally issued reports to British intelligence as agent 666, discusses the ex Deo phrase in several of his works. No slouch when it comes to religious scholarship, Crowley views the formula as cognate with the Gnostics’ IAO mnemonic as well as the Hindus’ system of a triumvirate godhood with a creator, a destroyer and a preserver.

In terms of Nazi ideology and religion, beyond a belief in warfare for warfare’s sake, the idea of total krieg and annihilation followed by posthumous victory serves as a species of jinx, a “we win either way” stratagem to fake out and discourage their enemies, draw young and stupid recruits and impress future generations of historians and the laity with their Crusader-like sacrifice. There is no doubt in my mind that the Latin motto was old hat to the occultists who formed the base belief for what was to become the Nazi cult, was known to Nazi occultists in the Third Reich and had currency with the various philosopher-cheerleaders of National Socialism in Europe, including Mussolini’s favorite court jester Julius Evola, who found Italian fascism a little too timid and sought greener pastures in Hitler’s Germany, and friend of and apologist for the Iron Guard in Romania, Mircea Eliade. The idea contained in the tripartite formula resonates with other pet ideas of the Nazis, such as Nietzsche’s “In the beginning was the deed,” Goethe’s idea hidden forces rush to the aid of the decisive man, warped interpretations of the opera Parsifal and so on. It wasn’t a coincidence Hitler and the other leaders of the Third Reich called the 16 martyrs “the Immortals,” for they had followed the path laid out by the formula to immortality, snatched up by the valkyries for endless recreation and entertainment in Valhalla. The Nazis propagated the notion of the nobility of fighting and dying for a doomed cause. I don’t subscribe to the nobility of it all, but they were right about the doomed part of their own cause. The “hidden forces” which they could have marshaled were the ethnic groups in the countries they conquered, many of whom in Eastern Europe and Western Russia were perfectly willing to go along with the Nazi program, but whom Hitler and other decision makers relegated to the class of subhumanity, preferring instead to believe in the secret aid of fairies and valkyries, shifting to solemn intonations about a new generation of miracle weapons about to emerge from the war industry when the gnomes and elves failed to appear on the battlefield marching under the swastika banner and the war was almost lost. It was Hitler’s greatest strategic mistake and cost him the war. From his point of view, though, countries such as Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, and even Czechoslovakia, were creations on paper which emerged by League of Nations fiat. Lithuania was no more a sovereign country in Hitler’s eyes than the Isle of Man or the Shetlands were independent of Britain at that time. It was political fiction and window-dressing to Nazi policy makers who, needless to say, weren’t intent on a multicultural Europe with a glut of small states to represent all the ethnicities. Beclouded by the “wealth of nations,” so to speak, on the geopolitical map, the Nazis lost their opportunity to consolidate Eastern Europe for the long march into Russia by paying lip-service to nationalist and statist sentiment, which would have cost them nothing. Not that it mattered so much in Lithuania specifically, because the only anti-Nazi resistance to arise was that of Soviet and Jewish partisans, despite claims made by the Lithuanian Nazi leader Brazaitis and others they had somehow engaged in “telegram resistance” and waged a war of pseudonymous attrition against Nazi poor judgment in the Lithuanian-language underground press. In the larger region, however, the Nazis could have built a base of at least temporary support, probably sufficient to tip the scales at the gates of Moscow, at Leningrad, or later at Stalingrad, or Kursk.

◊

The Other Crusade

While the Templars and Hospitalers have reasonable name-recognition, and the Leper Knights remain obscure, there was an entirely different crusade waged against infidels in the Middle Ages, one that doesn’t get much press even now, and one that didn’t take place in the Middle East.

The history of Lithuania is bound up with this crusade, the Teutonic Knights harrying the western borderlands and the Order of Sword and Cross in Livonia (Latvia) and points north along the Baltic coast.

How it happened that Lithuania supposedly defeated the Mongol hordes and took possession of Ukraine and Belarus, while a few German knights in East Prussia were immune to defeat at the hands of the soldiers of the vast Grand Duchy, no one quite knows, but it probably involved a sort of “Mouse that Roared” scenario among the Eastern Slavs in Belarus and Ukraine, who preferred to surrender to Lithuanians over Mongols and Tatars, as well as peace treaties between the grand dukes and khans.

Whatever the case, as every Lithuanian pupil knows, or at least knew in the recent past, the tide turned at Žalgiris, where the Germans were trounced by the Lithuanians and went to lick their wounds in their crusader castles in East Prussia, never to bother the peasantry again. Žalgiris is the Lithunian literal translation of Grunewald, also known as Tannenberg, located somewhat unintuitively in the former East Prussia, now in Poland. Recent scholarship has questioned what role the Lithuanians really played in the multinational force arrayed against the German knights at Tannenberg, who quit the field early, whether this was a strategic withdrawal and so on and so forth. The real history doesn’t concern us here, but the symbolic does.

Tannenberg carried deep symbolic significance for the Germans as well, so much so that they called a different World War I battle at a different location Tannenberg II, which they happened to win “against the Slavs.” Hindenburg even had a gigantic memorial complex erected at Tannenberg where the battle hadn’t taken place to celebrate the German victory in the rematch, restoring Germany’s honor tarnished several centuries earlier.

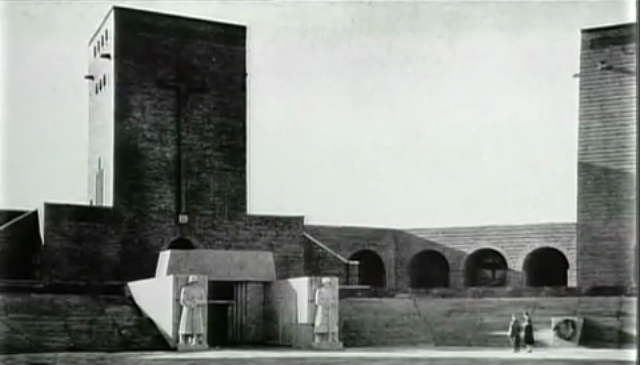

The Tannenberg memorial is important to this story, because it served as the model for the much smaller edifice at Obeliai. When Hitler came to power he had the Tannenberg complex redone in Nazi fashion using his personally selected architects. He attended the ceremony there on Hindenburg’s death. Hindenburg was entombed there as a centerpiece. One of the main features of the complex was a portrayal in figurines or bas-relief—the complex is now gone and information is scanty—of the final victory of the Germans over the Slavs and Balts in the East.

The Third Reich contained many other such necropolises, including the much-better preserved Totenberg memorial in what is now SE Poland, and the romanticism the Nazis attached to the Templars, the Teutonic Knights, the Holy Grail and similar subjects is well known, from Himmler’s reconstruction of Wewelsburg castle to include a round table with twelve places to Nazi archaeology at the site of the former Cathar castle in Languedoc. It might strike us as ironic in hindsight that some occultists consider the Latin formula provided above as the true message of the Holy Grail, a formula for immortality rather than a tangible vessel, and it is also ironic, through the distance provided by time and without any disrespect for the victims of Hitler’s Holocaust, that the Nazis identified themselves so closely with the Knights Templar, whereas the actual Templars were rounded up and murdered in order to steal their money and assets, a story not unfamiliar in Nazi-occupied Eastern Europe. It is no less ironic that Lithuanian pseudo-patriots in 1942 and 2013 are rallying around a monument based on the monument at Tannenberg commemorating Lithuania’s defeat at the hand of the Germans.

Teaching German youth about Hitler as Crusader Christ, from Nazi propaganda film, subtitles by American monitors

◊

Surely You Must be Joking, Mr. Vasil

Surely the little concrete monument at Abel, not much bigger than a headstone at some cemeteries these days, is innocent of association with Albert Speer’s vast Nazi Disneyland projects in the Third Reich. Any similarity is superficial, and down to architectural practices of the time. And surely the Latin inscription over monument, Rest in Peace, places this firmly within the Catholic rather than pagan realm. Where are the swastikas? There are none. Isn’t this apples and oranges, Mr. Vasil?

I’m glad you asked me that. Let’s look at these points individually and let’s take a look at the photographic evidence.

First, size: think globally, act locally. Lithuanian Nazis were mainly volunteers and carried out their work in the spirit of volunteerism. They didn’t have access to great resources and made do with what they had at hand.

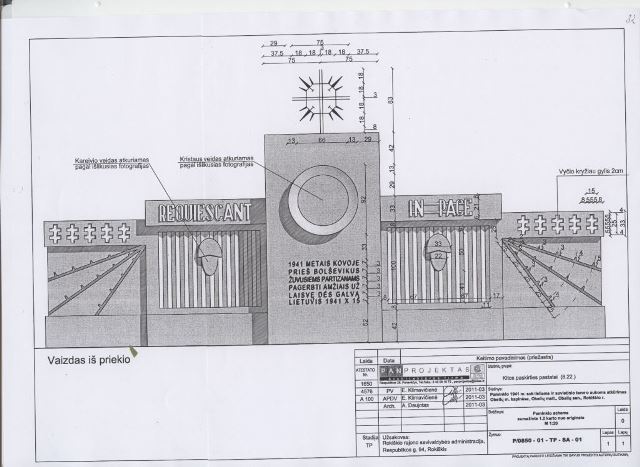

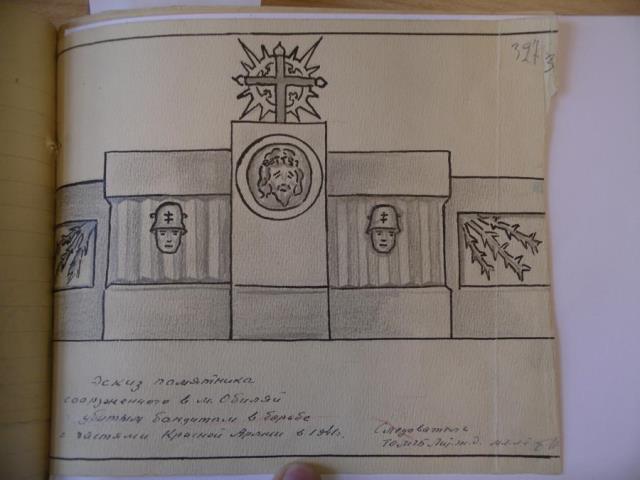

Second, similarity in architecture: look at the photographs and decide for yourself. All architecture is somewhat similar, employing right angles and corners commonly, but there is something in common at a deeper level here. Notice the inscription on the central plaque in the best available resolution of the single good photograph of the Obeliai monument. While the words are still illegible, they are clearly inscribed very close together almost with no breaks, almost in Greek koine style. Compare their superficial appearance with the Nazi plaque shown below. Compare the use of helmeted soldiers on either side of the center with Tannenberg. Notice the runic lightning on either side, very similar to the Nazi SS rune.

Third, the Catholic inscription: Himmler was Catholic, and the Nazis weren’t allergic to Latin. Why an Old Believer, a sect of Russian Orthodoxy, would use Latin in the monument he designed isn’t very clear, but it’s probably down to local mores.

Fourth, lack of swastikas: note the use of the double cross, a favorite runic symbol of Lithuanian fascists and pseudo-patriots to this day, on the helmets of the two soldiers. If the runic symbol didn’t suffer from association with Lithuanian Holocaust perpetrators in 1939, it does now.

Stylistically the Abel monument seems to follow the Nazi prototype. The six “martyrs” mirror the sixteen at Munich. The creator and builder was a Nazi sympathizer, fled the city for the countryside during Soviet rule and was tried and convicted, and sentenced to the Siberian gulag, after the war for painting “portraits of Nazi leaders.” The monument itself was likely funded through assets stolen from murdered Jews. The people involved all worked for the Lithuanian Railroad, which was notorious as a hotbed of Lithuanian Nazis, including former president Valdas Adamkus, a Nazi veteran, who wrote about its role in his autobiorgaphy, Likimo vardas — Lietuva [Destiny’s Name: Lithuania]. According to Herman Kruk the railway station in Vilna was the first location in the city to boast a sign claiming it was Judenrein, “Jew-free.” The final trains out of Vilna filled with people fleeing the Nazi invasion were hindered from leaving by ethnic Lithuanian railway station personnel, even as Luftwaffe aircraft hovered in the air to bomb the place, according to eye-witnesses. The Lithuanian Nazis in Abel were not just Hitler sympathizers, they were actively involved in gathering intelligence for the Abwehr before the German invasion of the Soviet Union and were harboring more than a dozen Nazi intelligence agents who were parachuted in behind enemy lines several weeks before the invasion.

This is no joke.

Postcard from 1916: Greetings from Abeli — the high-street

Entrance to central shrine within the Tannenberg complex, now completely gone

Hitler at Tannenberg ceremony, from the August 27, 1933 New York Times

Central shrine, Tannenberg

Another view, central shrine, Tannenberg

Best available photo of the monument the Lithuanian Nazis built in Abel, 1942. Note the text on the central object under the Aryan Jesus. It’s illegible in the photo, but is patently NOT what the restoration project has for its central text. Further, note the way the words run together with no spaces, similar to the Nazi monument in Munich, shown below

One of the monuments in Munich to the “blood-martyrs” of the Beer Hall Putsch

From the plan for the restored monument at Obeliai

Poor-resolution black and white photo of visitors to the cemetery at Obeliai, with fascist monument in background

Sketch of the original monument at Obeliai with notes by Soviet prosecutors at bottom

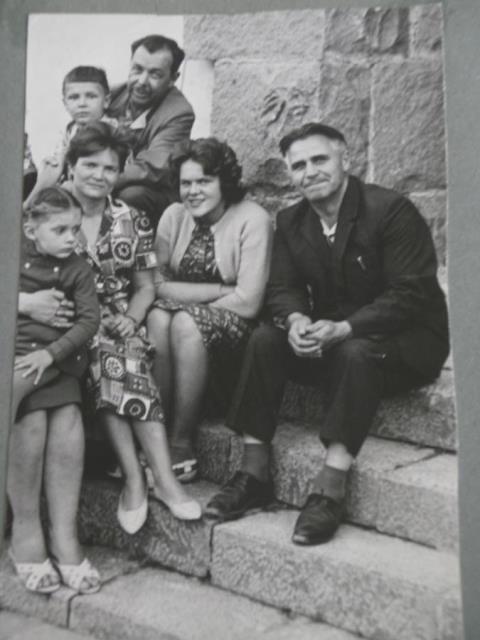

Guriy Kateshchenko and his family after he returned from Siberia, where he’d been sent for pro-Nazi propaganda and other crimes

Group picture of Jewish summer camp participants from Abel and surrounding towns and villages, August 13, 1928. The Katshchenko family survived World War II and the Soviet Union, while the Jews of Abel with very few exceptions did not.

◊

Doublespeak, Doublethink, Doublecaust

How is it that the Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of Residents of Lithuania, a body funded by the Lithuanian state from tax revenues, a state body within the European Union, supports through the major financial grant to date a project to resurrect a Nazi memorial which, although slated for destruction, actually expired through several decades of neglect? One of the Center’s major historians spoke at a fund-raiser for reconstructing the Nazi memorial monument in Obeliai.

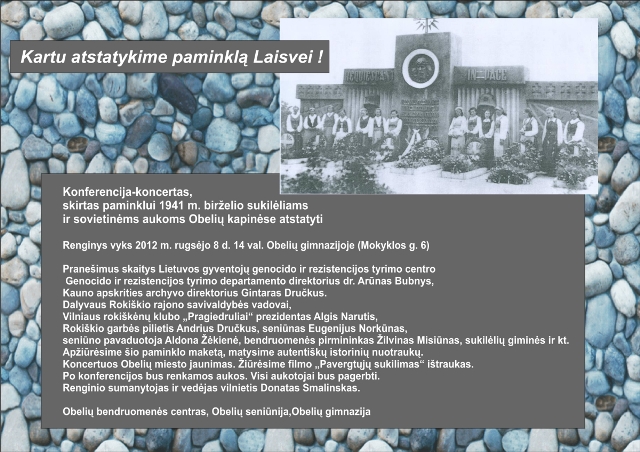

Advertisement for the fund-raiser: “Let’s rebuild the statue to Freedom together!” Event billed as a conference/concert, at the Obeliai Gymnasium, September 8, 2012

More fund-raiser agit-prop: “Let’s restore the statue to Freedom destroyed by the occupiers! Let’s memorialize the memory of the June Uprising in Obeliai”

The answer is not surprising. It is, as they say nowadays, that they “drank their own Kool-aid.” In other words, the majority of Lithuanians, including officialdom, don’t know what happened during World War II in Lithuania. They don’t know because it was “too dangerous” to know in former times. They don’t know who the Nazi gangsters and volunteers really were nor what they did. A vacuum has been created, a white-wash of history that only applies domestically, that only affects the Lithuanian public, who have been robbed of their own history by their own political and academic representatives.

In order to defend nativistic Lithuanian history as a pseudo-academic discipline, Lithuanian historians and other social engineers have set up a straw-man called memory, or narrative, or any number of other terms, to account for the discrepancies between their version of the empirical facts, and the rest of the world’s version of the events of World War II. (“Memory” is a euphemism for subjective history, since almost none of the people involved in the discussion were alive at the time or actually witnessed anything they could possibly remember personally. “Memory” sounds good, though, and strikes the right chord, especially at international conferences.) In this way it is possible to shunt inconvenient facts into the category of subjective recall, to juggle fact and belief and to keep the official version of Lithuanian history untainted and pristine from contact with the real world. It is part of the nationalist project and the nationalist religion, Lithuania’s only official religion, Statism.

So much of what passes for Holocaust research by Lithuanian researchers is a product of belief rather than facts. Writers use qualifiers and the subjunctive mood to cloak what boils down to, “I don’t think Lithuanians would do that.” Both nebulous “Memory” and the academic discipline of history are brought under the sway of and serve the belief systems of the people in power. George Orwell calls this phenomenon doubtlethink, the subversion of empirical reality to conform to the beliefs of authority figures.

The contradictions, however, threaten to tear apart the pseudo-patriotic nationalist “narrative,” obvious logical contradictions. First, to call upon all good patriots to support the rebuilding of the Abel monument means to accept the Third Reich’s “narrative” of victory at Tannenberg. It’s no cabal of Belarusian scholars in Minsk claiming they fought and won Žalgiris, it’s Lithuanians themselves saying the Germans actually won. Second, to claim the quisling Lithuanian Nazi self-appointed provisional prime minister Juozas Brazaitis aka Ambrazevičius actually represented the Lithuanian state or even the Lithuanian aspiration to statehood means to deny and renounce any tie between the interwar Lithuanian Republic and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, because that was the essence of the Lithuanian Nazi program, to break completely with the past and create a new racial state within the framework of Hitler’s New Europe and New Order. The Lithuanian Nazis made this abundantly clear numerous times, including in the LAF circular calling for the murder of Lithuanian Jews, where they claim to abrogate the ancient rights and privileges granted by the Lithuanian grand dukes to which Lithuanian Jews were accustomed, and according to which they could settle in perpetuity in Lithuania. Third, rehabilitation of the LAF is untenable because their role was to facilitate foreign—Nazi—occupation of Lithuania, murder the Jews and then disband, a role they played willingly and even cheerfully. No amount of word-play, no series of volumes of pseudo-academic studies will ever obfuscate that basic fact, that they did not raise a hand against the foreign occupation of Lithuanian territory and were the instrument for that occupation, as well as inspiration for the Nazis to go forward with the total extermination of all Jews in Europe. Fourth, attempts to export the “Doublecaust” fail because the numbers aren’t there. Compare 96-98% of Lithuanian Jews murdered in cold blood to Soviet support for Lithuanian language and philology projects and a net increase in the Lithuanian ethnic population under Soviet rule, and all attempts to posit a double genocide fall flat, including the attempt to reserve a special meaning for genocide in that same Lithuanian language the Soviets fostered so carefully over the decades as a value in its own right.

In sum: the Lithuanian Nazis, also known as the Provisional Government, LAF, self-defense battalions, TDA, auxiliary police and special squadron, sought to destroy Lithuania in order to carve out a new niche within Hitler’s Greater Third Reich for themselves and their friends. They presumed to abrogate historical continuity linking the Republic with the Grand Duchy and to extinguish the Republic in favor of a new Nazi territorial unit in which they sensed prospects for the enhancement of their own personal power and wealth. The monument to the fallen Lithuanian Nazis at Obeliai was an emulation of shrines erected in Germany for the new cult of the blood martyrs. Attempts to resurrect the monument, lost to neglect rather than conscious intent, are predicated on historical ignorance as well as a desire to rehabilitate and glorify Lithuanian Nazis.

◊

The Way Forward

Friends of Lithuania within EU leadership positions need to give their Lithuanian colleagues the proverbial EU nudge behind closed doors etc. etc. and tell them this won’t fly. The Lithuanian state, now under Social Democratic Party rule, needs to disband the commissions and agencies set up by Nazi apologists in earlier administrations, including the Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance etc. etc. and the sometimes Presidential, sometimes Prime Ministerial but always funded by parliament Commission to Investigate and Assess the Crimes of the Nazi and Soviet Occupational Regimes in Lithuania. The employees and “dignitaries” of these two bodies need to get the boot and be thrown out unceremoniously. They are doing irreparable damage to Lithuania’s reputation in the world and doing it on the taxpayer’s dime. Feints at “Holocaust education” by the Ministry of Education and Learning need to be replaced with a “just-the-facts, ma’am” approach in textbooks at the appropriate grade level. Politicians who already understand and know Lithuanian history need to loudly and roundly condemn the Nazi Brazaitis as a Lithuanian quisling and the LAF and etc. as illegal and criminal organizations. Place-names, streets and alleys named after these Lithuanian Nazis need to be renamed, and it would be a nice gesture if they were to bear the names of Lithuanian rescuers rather than murderers of Jews. Finally, legislation making it a crime to deny some sort of Soviet genocide against the Lithuanian people need to be repealed, even if they haven’t ever been enforced, to rectify Lithuania’s projection on the international scene.

None of these points cost anything at all, with the exception of new street signs. In fact they save considerable money. All that’s needed is for the leaders to lead the way on principle without too much regard for the political fallout or gains to be had.

Real Lithuanian patriots aren’t Nazis and have never supported by thought or deed the foreign occupation of Lithuanian soil. A loud minority of historically ignorant pseudo-patriots have seized the agenda for a time, but their time is limited and the tide of history and civilization is against them. For those looking forward, to the future, these very basic measures, the points outlined above, are sufficient to place Lithuania firmly within what is called the Western framework of democracy, politics and history, and no one is demanding crocodile tears for people who were murdered long ago by people living Lithuanians do not remember.

§§§

Addendum: The psuedo-Catholic Lithuanian internet newspaper bernardinai.lt reported, after this article was written but before it was posted or published, that the monument at Obeliai has been restored. Whether this means it is back in the cemetery, or sitting under wraps somewhere, I have no idea. The report went on to say that while the project has been completed, funding it hadn’t, and the Nazi apologists and iconographers are still seeking donations from the public.