CEMETERIES AND MASS GRAVES | POLITICS OF MEMORY | LITVAK AFFAIRS

◊

by Julius Norwilla

◊

The Holocaust Mass Grave Site

The best way to reach the mass killing site in Garliava (Yiddish Gúdleve, Polish Godlewo), is to take a train from the central train station in Kaunas. It is just one stop. The railway runs south, through a picturesque valley of the languid river Jiesia. Garliava is a township historically in the Suwałki region. It is named after an ancient landlord and noble family Godlewski. It seems that twentieth century ethnic purity zealots renamed the township into Garliava to sever any obvious link to the personage commemorated by the town’s naming, thereby reducing the historical chronicle of the entire region to a narrow and assertively ethnonationalist narrative

When you step out of the old railway station in Garliava, the town itself is still one kilometer away. The train line and the station were built in 1862, and one can wonder, what the point was, with the then cutting-edge train technology of the time, to make a long detour around the town and build the station somewhere in the middle of the fields, or as one might put it, right in the middle of nowhere?

When you head on to Garliava itself, you see on the right the brown color landmark sign marking the Jewish killing site (Žydų žudynių vieta) 700 meters away. There is also a black stone sign, as we call it, one of the late Lord Greville Janner’s signs, erected in the 1990s. There is a road along the river that is accessible only for special all-terrain vehicles. The clammy and serrated valley is excluded from local farming. Locals do come here for barbeques.

The fenced-in Holocaust mass grave site in Garliava (Gúdleve) with the stone monument to the victims. Photo: Julius Norwilla / DefendingHistory.com.

The kilometer-long walking route has no further signposting, and an attempt to find the mass grave of the town’s Jews can be confusing and frustrating. But once on site the grave is on a slope, easy to find, fenced in and well kept-up. The mass grave is one big grave, 50 meters long, with a modest stone monument in the middle. The inscription is in Yiddish and Lithuanian, explaining that on the site on 28 August 1941, Hitlerist killers and their local assistants killed 247 Jews — children, women and men.

Bilingual (Yiddish-Lithuanian) monument at the Jewish mass grave at Garliava. Photo; Julius Norwilla / DefendingHistory.com.

The entry in the Lithuanian Holocaust Atlas relates the events thus:

“On the day of the massacre, a few dozen men were selected in the barracks of the 3rd Unit of the 1st Battalion in Žaliakalnis (in Kaunas city). The men led by Lieutenant Juozas Barzda (some witnesses also mentioned lieutenants Anatolijus Dagys and Bronius Norkus) boarded two trucks and set out for Garliava. Having reached the town, the trucks stopped at the synagogue where the Jews were being kept. Local police officers and white-armbanders forced the Jews from the synagogue to the site of the massacre. There were men, women and children. The policemen and white-armbanders surrounded the murder site and, group by group, led the Jews to the pit. First, they killed the men. They were lined up near the ditch and shot in the back from a distance of a few meters. The shooting was carried out at the officers’ command. The massacre began late in the afternoon and ended after dark. Some of the troops of the battalion had flashlights, which they used to finish off injured victims. … Jäger indicated that 247 Jews were killed in Garliava: 73 men, 113 women and 61 children.”

The perpetrators, official militia members, policemen, volunteers in military and paramilitary units were all local Lithuanian activists. Naming perpetrators as “Hitlerist killers and their local assistants” is a curious turn of phrase a little bit in the spirit of Orwell’s discoveries on the perversion of language for political and historical manipulation. The soldierly commands to shoot to kill the victims were all given in their native tongue. Lithuanian military and police officers were not some zombies, some brainwashed abstract “Hitlerist murderers,” but rather straight “Lithuanian patriots” to whom vast space is dedicated in Vilnius’s Genocide Museum, and many others, turning them into “freedom fighters and national heroes.” The massacres of Jewish communities all over Lithuania should be classified as an ethnic cleansing operation, under Nazi German occupational command, auspices, reassurance and inspiration.

In Lithuania, there are around 230 mass grave sites like Garliava. These massacres all over the country were carried out in the same professional manner and in an increasingly effective and efficient way. The monument in Garliava is a typical one. Bearing witness to a heinous crime of annihilation of the entire local Jewish community, it just states the fact, lacking even a word of empathy. Besides that, the Lithuanian inscription is grammatically wrong. In Lithuanian, when in plural accusative, a noun has a different ending than its adjective. That means three words for “children, women and men” need a correction. The one-sentence text was made by folks who do not know elementary Lithuanian grammar, and supervised by such as did not think correction was worth bothering with in this case. For inscriptions in an official state language, simple grammatical errors have an effect of detracting from seriousness, solemnity, and sincerity as viewers who are native speakers of the language rapidly see the errors.

After dozens of inspections of Jewish mass grave sites, I can confidently assure the readers that an inordinate number display a salient mistake of one sort or another. In each case, a letter should be sent to the Department of Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Culture. Working toward accuracy and dignity of signposting is one of the major motives for visiting such sites across the country.

◊

The Old Jewish Cemetery

The old Jewish cemetery is at the outskirts of Garliava, beside the busy ring road known here as KK 139. It is obvious that the biggest part of the old Jewish cemetery has been buried under the ring road at the time of its construction by the Soviet administration in the 1970s. The surviving part of the cemetery is fenced and well-kept-up. Unfortunately, there is rather little left of the original stones. The vast majority were stolen, and can be found, inter alia, in local foundations and road ballast.

The remnants of the Jewish cemetery in Garliava are now neatly fenced in (much of the cemetery and extant human remains lie outside the fence). Photo: Julius Norwilla / DefendingHistory.com.

In the middle there is an early 1990s inscribed stone, ordered by newly independent Lithuania for very many towns, denoting it as the old Jewish cemetery. The inscription is in Lithuanian and Yiddish, topped with a star-of-david. Like the vast majority of Jewish cemetery stones across the country, it came “from the factory for all of them” with no mention of the name of the town. A dozen broken concrete monuments and chunks of three broken matséyves (Jewish gravestones) are scattered all over the site. Are these three stones bearing Hebrew lettering from here or were they brought here from somewhere else? It is still possible to read a name of Yitskhok-Nakhshon [?] Sherira who passed away here in the mid 1920s, as well as of a woman Shéyne (see second image below).

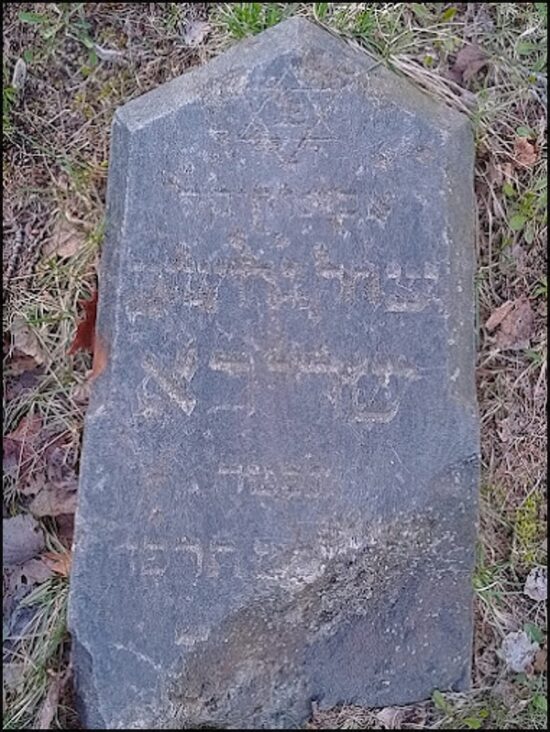

Gravestone of Yitskhok-Nakhshon [?] Sherira who passed away in the mid 1920s here. Photo: Julius Norwilla / DefendingHistory.com.

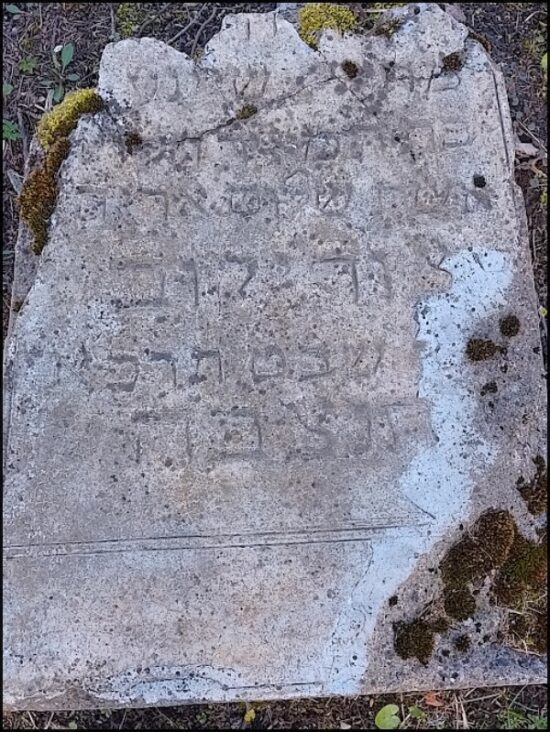

Remnants of the stone of the woman Sheyne, husband of Sholem-Aryeh [?]orilov. Photo; Julius Norwilla / DefendingHistory.com.

Within the town of Garliava, we could not find a single mention of the centuries of Jewish life in the town up to that fateful day in 1941. In Berl Kagan’s classic Yiddish Encyclopedia of Jewish Cities, Towns and Villages in Lithuania (New York 1991), four columns (pp. 59-60) are devoted to the town’s rich Jewish history and culture, which include a number of rabbinic authors of treatises that continue to be studied today. Kagan concludes the entry with a transcription of two gravestones from Jerusalem, from 1866 and 1767, which proudly state the deceased’s town of origin: Gúdleve.