OPINION | MUSEUMS | POLITICS OF MEMORY | SHTETL COMMEMORATIONS

◊

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

◊

This weekend, the new monument to 2,400 Biržai Jews, massacred on August 8, 1941, will be unveiled in Biržai, a town in northern Lithuania known in Yiddish as Birzh. On that fateful day in Pakamponys forest, German Gestapo officers and their Lithuanian accomplices murdered 900 children, because they were Jewish children, 780 women, because they were Jewish women, and 720 men, because they were Jewish, too. The locals call the site “the Biržai Jews’ grave”.

That day, more than one third of the inhabitants of that old historical city were massacred. A vibrant community was destroyed and trust in Biržai as a safe place to live was wholly undermined. This old wound had not been taken care of properly up until now. There is a memorial stone at the site of the massacre, the site itself is covered with tiles. There is a memorial inscription, too. However, all those people with their lives and their dreams remained but a number in stone. People behind the new memorial decided to fix this, and now we have more than five hundred names carved on a steel wall. This difficult task required a lot of effort. Alongside with the people, the murderers also destroyed the documents attesting to their lives.

◊

What does the Town’s Official Museum Think?

The first thing I did, when in Biržai, was to look for Jewish traces at the Biržai Region Museum “Sėla”, established in the Biržai Castle. The staff was pleasant and helpful. Although busy with preparation for the upcoming events and distinguished foreign guests, they found some time for me, too. I was given a Biržai map and directions to objects that may be of interest to me. The museum itself is very interesting, too. However, I did not find much information on my topic there. I am an atypical history lover in that I like to see the exhibition from “the wrong end”. Historians usually favor historical materialism and begin the story from the Stone Age (I always have questions about the sort of stone they used, where they got it from and how they traded in it…). But I am keen on a certain world creation theory: I believe that I received the world already complete and history should explain to me how this task was accomplished, therefore I approach the past from the present. Perhaps that is why, having freed myself from the museum staff’s care, I approached the exhibition from its end.

I found Biržai athletes’ achievements there, which were impressive, but I had already seen that on TV. Then came Sąjūdis and the struggle for independence; after them, the Soviet times with a Young Pioneer’s uniform and the main attribute of a Soviet grocery store: the scales. Of course, I am slightly joking here. The stands are many and full of diverse materials: for example, “The Chronicle of the Catholic Church in Lithuania” (“Lietuvos katalikų bažnyčios kronika”) samizdat, published as a book, and a collection of Soviet newspapers, including a copy of the “Banner of Stalin” (“Stalino vėliava”). Compared to the Soviet times, there really is more freedom and pluralism.

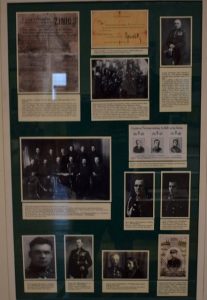

Then come the deportations, the partisans, the occupations, and… here, I stopped for a moment. At the center of the stand telling the story of the Soviet-Nazi war, there was a white armband of the “Lithuanian Auxiliary Police” (“Lietuvių pagelbinė policija”, “Litauische Hilfspolizei”).

Yes, the stand is full of photos. Some people in uniforms, a German bomber dropping bombs. Jews, marked with yellow stars. Documents, attesting to the Lithuanian suffering. Firearms, graves marked with Lithuanian patriotic symbols. I wanted some explanations. As is appropriate in the digital age, some important information was provided by the stand. I “learned” of the LAF “insurrection”, of the Provisional Government, established on June 23, and about the massacres of the Biržai Region Jews. Two parallel worlds. The Provisional Government operated from June 23, 1941, to August 5, 1941; Jews were massacred during July and on August 8, except for Vabalninkas Jews, who were murdered on August 26. The time period is the same, but the relation between these two events is not explained by the museum. I proceed to a stand that tells the story of the annexation to the Soviet Union, but my grim thoughts stand in the way of understanding the notion, popular among Lithuanians, that the Soviet occupation destroyed Lithuanian-Jewish relations and led to the Holocaust.

Questions hover over this weekend’s festivities:

Will the exalted foreign visitors —wined, dined, medalled and photo-opped with high gov. officials — have the courage to speak up in public about the town museum continuing to honor Holocaust collaborators? Can you — ethically and logically—honor both the victims and the perpetrators? How can one prevent even the best of memorials from serving as deflection for glorification of the collaborators? What is the larger meaning of “truth out in the forest” vs. “obfuscation in the city center”?

Although upheld by many famous historians researching the period, to me it seems like a work of propaganda and an attempt to justify those who took part in the Holocaust. Memoirs of those deported in 1941, in which the friendly relationship between Lithuanian and Jewish deportees is emphasized, stand as evidence that that brutal violence did not destroy the trust between the peoples. Yes, this relationship ended with the catastrophe in Lithuania. But there were other influential actors beside the Soviets in Lithuania at the time, and Nazi propaganda was dominating during the catastrophe, so perhaps it would be honorable to stop shifting blame and admit that Lithuanians who took part in the massacres gave in to the Nazi propaganda and that, even before, antisemitism had not been a concept foreign to them, either.

◊

Holocaust Collaborators are Glorified, Too

On the first floor, I found a hall dedicated to the interwar Independence. My mood was ruined by Kazys Škirpa, featured in a stand for the Wars of Independence.  He was the leader of the LAF Lithuanian Activist Front), whose 1941 “insurrection” had such horrible consequences to Lithuania and, especially, Jews. Yes, the Christian tradition does teach us to forgive a repenting sinner if they try to redeem their sins with subsequent good deeds. But when it comes to attempts to cover subsequent crimes by previous merit, we usually call that manipulation and falsification of history. I would understand if Škirpa was featured in that other stand, next to the “Lithuanian Auxiliary Police”, accompanied by an explanation that the LAF not only organized the “insurrection”, but was also inciting Lithuanians to “get rid of Jews”; especially when Škirpa’s influence upon the latter events was much more prominent than to the Wars of Independence. Perhaps there was a lack of prominent soldiers from Biržai who took part in the Wars of Independence? Next to the museum, I found not even one, but two monuments to these struggles. They had both Lithuanian and Jewish names inscribed on them: eleven Knights of the Order of the Cross of Vytis and forty-six volunteers, including non-Lithuanian names of Jokūbas Chaitas, Mitelis Kaplanas, Viktoras Štreitas.

He was the leader of the LAF Lithuanian Activist Front), whose 1941 “insurrection” had such horrible consequences to Lithuania and, especially, Jews. Yes, the Christian tradition does teach us to forgive a repenting sinner if they try to redeem their sins with subsequent good deeds. But when it comes to attempts to cover subsequent crimes by previous merit, we usually call that manipulation and falsification of history. I would understand if Škirpa was featured in that other stand, next to the “Lithuanian Auxiliary Police”, accompanied by an explanation that the LAF not only organized the “insurrection”, but was also inciting Lithuanians to “get rid of Jews”; especially when Škirpa’s influence upon the latter events was much more prominent than to the Wars of Independence. Perhaps there was a lack of prominent soldiers from Biržai who took part in the Wars of Independence? Next to the museum, I found not even one, but two monuments to these struggles. They had both Lithuanian and Jewish names inscribed on them: eleven Knights of the Order of the Cross of Vytis and forty-six volunteers, including non-Lithuanian names of Jokūbas Chaitas, Mitelis Kaplanas, Viktoras Štreitas.

Replacing Škirpa’s figure for those of, say, martyrs of the Wars of Independence Jokūbas Chaitas or Mitelis Kaplanas would only make the exhibition more impressive. But it seems that the time is not yet ripe for such changes.

The museum also houses an interesting exhibition on the religious diversity characteristic to the Biržai Region. After exploring all the exhibitions, I still felt like something is missing. So I asked the staff once more: perhaps there is something more to the museum, something I did not manage to see, something about the life of Biržai Jews? After all, they would comprise more than a half of the city’s population during various historical periods. The response was simple and unapologetic: “You are not the first one to complain about that…” It seems that, so far, the narrators of history are happy with Jews peacefully lying in graves. But can such history, Lithuanianized by convenient omissions, really ever be complete?

Having visited the museum, I went to the Biržai Jewish and Karaite cemeteries. I wanted to see the monument to the dozen Jews who were shot in July. It is not yet their time to get their names back, they remain but a number above the tombstone.

Every visit to a cemetery is an encounter with history. Another tombstone, right next to this one, caught my eye: “Bezemacher Hirš [Hirsh], 1884-1945” written on it. How horrible, I thought to myself, an old Jew survived the horrors of the War and died right after its end. I asked around and learned the whole story, which is even more horrid. After the war, food in the city was scarce. Hirsh would walk around the surrounding villages, trying to get some food for his family. He was old and did not hear well. On that fateful day, armed “protectors of the people”, the “istrebitels” [members of the USSR “destruction battalions”], saw him and ordered him to stop. Hirsh, however, really could not hear them and continued walking. The “istrebitels” were young men and could have run after him and stopped him, if only they wished to do so; but that appeared too dangerous to them. Shooting was a simpler option, so they shot Hirsh down. Such were the times, indeed: people were being arrested, deported, murdered. The Republic of Lithuania has an institution that talks a lot about the “genocide” of the Lithuanian nation carried out back then. Hirshš’s death does not fit into this historical concept… So I am talking about it to keep us from forgetting. Forgetfulness enables all sorts of manipulators.

◊

The New Memorial

From the Jewish cemetery, I headed to Pakamponys to check out the new memorial. I found it impressive. The quantity of names is impressive, too, at first one could even forget that it is but one-fifth of the massacred. Black plaques with a short history of Biržai Jews in Lithuanian and English stand next to the memorial. The English version reads:

The first Jews arrived to settle in the Duchy of Biržai at the end of the 16th Century. They were invited by the Duke of the House of Radziwill (Radvilos), who promised them protection from their neighbors. There are documents from the 1600s which mention Jews settling in Biržai and receiving the rights of settlement.

Jews made a living trading in flax and wood. There were weaving and knitting factories, flour mills, furniture manufactories, tanneries, a winery, a dairy industry, a pottery factory, an electric station, and several other small industries as well as a Jewish bank.

The daily activities of the Jews of Biržai were filled with normality, social awareness, and religious devotion. There were Rabbis, synagogues, houses of Torah study, a kindergarten, a Tarbut—secular Hebrew primary and high school. There were charitable organizations, a home for the elderly, an orphanage, a health clinic, Jewish sports clubs and a number of Zionist organizations. There were two musical groups which were famous throughout Lithuania. A Jewish photographer immortalized images of Biržai.

One month after the Germans entered Biržai, Jews were evicted from their homes and forced into a ghetto. A Jewish doctor, renowned for his care of all citizens, rich and poor, was the first of the fifteen victims, who were shot by German soldiers and buried in the Birzh Jewish cemetery.

On the Eighth of August 1941, 2400 Jews, 900 children, 780 women, and 720 men were brought here and brutally murdered, shot by Gestapo officers and about 80 Lithuanian collaborators.

Here, in this forest, is buried the once vibrant, pulsating Jewish community of Biržai, ordinary people, men, women and children, annihilated because they were Jews.

Hundreds of names of victims of the mass murder are not known but we mourn their loss.

“Never forget.”

Both the Lithuanian and English texts end with “Never forget” in the Jewish alphabet.

Another plaque, on the other side of the memorial, tells us that it was erected by the efforts of the Society for History and Culture of Biržai Jews, aided by a number of persons from South Africa, the US, France, Israel, Lithuania, and the UK. These people did a good deed and brought back an important piece of the history of Biržai Jews. Those who look for, but cannot find it in the exhibitions of the museum, will find something here.

“On the other hand, it is not a problem that foreign Jews should be expected to take care of.”

I also remembered that it was not only Jews who were murdered at that spot, but also some people who were deemed “Communist” by the Nazi collaborators. There is no monument to them.

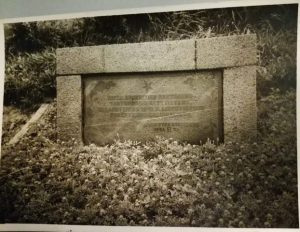

Next to the stairs leading to the stone on the “Jews’ grave”, remains of a concrete foundation can be seen. In Soviet times, a memorial stone to those several dozens of murdered people was standing here. The government of independent Lithuania decided to destroy the memorial stone and now one can only see it in old photos. Yes, the wording of its inscription was very “Soviet”, but was razing it to the ground really the best option?

A grave is a grave, it should be marked, and a plaque with the victims’ names is needed. On the other hand, yes, it is not a problem that foreign Jews should be expected to take care of. It is the Lithuanian government that cannot yet construct an honest narrative about it, even in monuments far from city centers.

◊

Translator’s note: The Lithuanian version of the text reads about the same as the English one, but, for purposes of precision, its full translation is provided here.

The Jewish community was established in the Duchy of Biržai in the late 16th century, during the years of rule of Prince Kristupas Radvila Perkūnas (“Thunder”). The community grew in the 17th century. In the 1630s, Kristupas Radvila II took up the initiative to settle the city Jews in one spot and gave them a permission to build a synagogue. Jews would build their houses on the two streets leading to the market square.

In 1765, the Biržai Jewish community was comprised of 1040 Jews. In the late 19th century, it was already 2,510 people, i.e., 57 percent of the city’s inhabitants.

Jews made their living as small-scale businesspeople, usually in trade and crafts. Weavers’ and knitters’ shops, flour mills, furniture and pottery manufactories, tanneries, a winery, a power station, and other small industrial enterprises operated in Biržai.

In the interwar years, the Biržai Jewish community was concentrated on contemporary Žemaitės, Dagilio, Karaimų, Vilniaus, and Kęstučio streets. There was a Jewish people’s bank, three Jewish sports clubs, a Zionist organization “Mizrachi”, several synagogues, Javne and Tarbut schools, a kindergarten, a health clinic, an orphanage, a shelter for the poor, and other organizations. Out of 228 shops, 160 belonged to Jews. One of the photographers who immortalized the images of interwar Biržai was also of Jewish ethnicity.

On July 28, 1941, the Biržai Jews were evicted from their homes and forced into a ghetto, formed around a synagogue and a Jewish religious school. A Jewish doctor, renowned for his care of citizens of all ethnicities and social strata, was the first victim of the Nazis.

On August 8, 1941, the mass extermination of Jews began. Here, in Pakamponys forest, around 2,400 Jewish citizens of Biržai were brutally murdered: 900 children, 780 women, 720 men. They were shot by German Gestapo officers and their Lithuanian collaborators.

The Biržai Jewish community is buried here. Common people—men, women, and children—murdered for being Jewish.

We mourn the loss of all of them, including the hundreds whose names we do not know.

Let us not forget them…

Let Us Never Forget