E Y E W I T N E S S R E P O R T / O P I N I O N

The ceremony today to commemorate Lithuanian Holocaust victims at Ponár, the country’s largest mass murder site, outside the capital city of Vilnius, on the day officially known as Day to Commemorate the Lithuanian Jewish Victims of Genocide, went off pretty much as most official commemorations do here: inappropriate and with seeming desperation to focus on any topic except the circumstances of the actual Lithuanian Holocaust—the massive collaboration and participation that led to the country’s having the highest proportion of Holocaust murder in Europe.

Ponár is the site’s Yiddish name. It is today Paneriai and is known as Ponary in Polish.

The official date, the 23rd of September was marked this year on the 24th, apparently so officials wouldn’t have to interrupt their weekend break.

Holocaust survivors and advocates have pointed to more appropriate dates, such as 23 June when the genocide was first unleashed by the pro-Nazi Lithuanian Activist Front and other nationalists in 1941, or 29 October which marked that year the murder of some ten thousand Kovno Ghetto Jews in a single day (following the previous day’s “Great Action”; it was the largest one-day massacre in the history of the Baltic states). Instead officials chose the 23rd of September presumably because the liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto on that date in 1943 can be packaged as a purely German decision (though the Ponár shooters were, as ever, mostly or entirely local nationalist volunteers). Still, an official remembrance day observed each year acquires its own momentum.

Parliamentary deputy chairman Erikas Tamašauskas delivered an inappropriate speech without even a hint of understanding what took place in Lithuania during World War II. He claimed certain people were inflaming Jews and exploiting the Holocaust and that he was especially concerned that these people include younger people who have no direct knowledge of the Holocaust. He then called on Jewish Holocaust survivors to stop competing with Lithuanian deportation survivors for attention and sympathy, and called on Holocaust survivors to build bridges of understanding with Lithuanians.

The right wing “Jewish MP” Emanuelis Zingeris, a talented philologist and master political tactician, now head of the Lithuanian parliament’s foreign policy committee, used the occasion to launch into a speech on Iran, scaring the aging survivors who gather each year. He told them he hoped they wouldn’t meet next year around a stone monument similar to the one at Ponár (he turned to point at it theatrically) to commemorate the State of Israel. Iran is obviously a very vital issue, and Mr. Zingeris is to be thanked for his concern. But it is an issue that he could perhaps most productively raise in Prague, Brussels and Strasbourg where his efforts seem to be instead in the cause of the 2008 Prague Declaration calling for universal acceptance of the equivalence of Nazi and Soviet crimes. He was the only Jew in Europe to sign the declaration.

He also delivered a message from his mother, a Holocaust survivor, calling for peace, love and understanding (but didn’t mention his late father, a heroic Soviet war veteran of the campaign against Hitler). In some views, he has been the x factor distinguishing Lithuania’s role in exporting Prague Declaration politics, and particularly, in persuading the United States State Department and the Israeli Foreign Ministry to acquiesce in some degree, presumably in a diplomatic quid pro quo for support, in the case of both countries, on major geostrategic issues. Some participants in a recent DC Holocaust Museum tour reported to DefendingHistory that US embassy officials tried to dissuade them from being in touch during their time in Vilnius.

But there were appropriate speeches too. They were brief, but commemorated the victims, and showed how straightforward it is to do that without entering into political discussions on the debates currently raging.

The Israeli ambassador to Lithuania and Latvia, Hagit Ben Yaakov, paid her respects to the victims. She was the only speaker to mention local collaborators.

Misha Jakobus, director of the Sholem Aleichem school in Vilnius, delivered a short and solemn address in Lithuanian and in Yiddish.

Inna Frishman, a pupil at the Sholom Aleichem school in Vilnius, speaking at the Ponár memorial. Photo: Jewish Community of Lithuania information service.

The most memorable speech of the day was delivered by one of his high school pupils, Inna Frishman, who recounted the Holocaust history of her grandmother from Slutsk (Belarus). Although her particular family history happens to be rather far from the actual historic narrative of direct relevance for the Lithuanian Holocaust, and there was no mention of the killers from Lithuania who were voluntarily dispatched to Slutsk, it was moving and deeply relevant to the Holocaust, and how it can be remembered by young people today ever more removed in time from the events. Ms. Frishman’s detailed talk was an outstanding example of how Holocaust commemoration can be part of broad intellectual education and growth, contributing significantly to humanism, empathy and concern both for one’s family past and for a better world for all.

The official chief rabbi of Lithuania Chaim Burstein delivered a memorial prayer in Hebrew. The Chabad rabbi, Sholom Ber Krinsky, was among the dignitaries in attendance.

The school pupils at the event conducted some sort of elaborate and sincere performance involving cardboard boxes whose meaning no one seemed to understand, but in comparison to the performances by Zingeris and Tamašauskas, it was more relief than theater of the absurd. For those who managed to get close and see the display (difficult to see because of its horizontal layout near the ground), it was actually imposing and indicated that a huge amount of work had been invested: thirty five boxes put into place to make a large star of David, half silver and half red, over the words in Lithuanian for “The Shoah in Lithuania.”

None of the tiny number of ghetto survivors present was asked to speak this year, as if they have been written out of the script while yet they walk this earth. But the prominent and beloved survivor, resistance veteran and educator Fania Yocheles Brantsovsky laid a wreath on behalf of the Association of Ghetto Survivors, concurrent with the Jewish community’s wreath.

There were calls to attention and perfectly executed wreath layings by the ample military honor guard (plus women in ethnic attire), which had earlier this year done the same—actually a lot more—to welcome the remains of the 1941 Nazi puppet prime minister whom the government reburied with full honors and glorified in a series of state sponsored events financed by order of the prime minister and the culture minister. Equivalent, symmetrical, double. Double genocide, double games, double talk.

There were calls to attention and perfectly executed wreath layings by the ample military honor guard (plus women in ethnic attire), which had earlier this year done the same—actually a lot more—to welcome the remains of the 1941 Nazi puppet prime minister whom the government reburied with full honors and glorified in a series of state sponsored events financed by order of the prime minister and the culture minister. Equivalent, symmetrical, double. Double genocide, double games, double talk.

Dr. Rachel Margolis outside her home in Rechovot.

Nobody mentioned Dr. Rachel Margolis (Rechovot), whose rediscovery and 1999 publication of the long lost diary of the Polish Christian eyewitness Kazimierz Sakowicz made way for the truth about Ponár to become widely known. Nearing her 91st birthday, she is afraid to return to her native Vilna for a final visit because of the campaign of prosecutors and others to defame her and other survivors for having joined the anti-Nazi partisan resistance. She has been called “the most tragic Holocaust survivor.” In fact, Lithuania is the only country to have targeted Holocaust survivors for “war crimes investigations” because they escaped Nazi ghettos to join the partisan resistance in the forests.

Nor was there any mention of the first such target of prosecutors, Dr. Yitzhak Arad (Tel Aviv) who edited the English edition of the Sakowicz diary for Yale University Press in 2005. In addition to Arad and Margolis, a third Israeli citizen, Joseph Melamed (also now a Tel Aviv resident), head of the last active association of Lithuanian Holocaust survivors, was targeted by Lithuanian prosecutors, not for war crimes but for “libel” against Lithuanian heroes in his 1999 book, Crime and Punishment. He was visited by liaison officers of Interpol in 2011.

Arad, the founding director of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, was the first Holocaust survivor to become a target of “pre-trial investigations” here. In a gesture of trust and good will, he was persuaded to join the Lithuanian government’s commission on Nazi and Soviet crimes and was then himself accused of war crimes for having joined the anti-Nazi resistance. The commission (called up to place a wreath before the monument today) was recently relaunched and expanded without him (or any apology to him), and is expected to play a key role in a new effort planned for 2013, during Lithuania’s presidency of the EU, to persuade the European Union to accept Double Genocide as “unified European history.” Holocaust survivors in Israel, and in the United States, have expressed their robust opposition to renewal of the so-called “red-brown commission.” Over the years, it has attracted widespread opposition, principally because of its active role in publicly supporting the Prague Declaration of 2008 and similar “double genocide” documents which continue to adorn its website. It has to this day failed to publicly condemn the prosecutorial and media campaign against its own former member Dr. Arad.

Keeping with the day’s theme of often striking the wrong note, a rather jazzy—sleazy 70s jazz—version of the Jewish partisan anthem, Zog nit keynmol, closed the ceremony.

Nevertheless, the event had its own profundity and gravitas because the living Jewish Community of Lithuania was so well represented. The community’s leaders were all in the front rows among the ambassadors and foreign diplomats in attendance, with the exception of chairman Dr. Shimon Alperovich, who is recovering from serious illness.

The gravitas came from the crowd that turned out, virtually entirely from the community, from toddlers in their mothers’ arms to the very aged. In a sense their presence and genuine ambiance of brokenheartedness over a murdered people outweighed, or even rendered irrelevant, much of what was coming from the podium.

By contrast, almost none of the “Jewish” institutions that figure in state PR in classy downtown Vilnius bothered even to send a representative. There were no groups of foreign tourists to impress this week. Nobody came from the Vilnius Jewish Library, the Vilnius Yiddish Institute, the Kabbalah Center, or the Center for East European Jewish Studies. The one exception was the Jewish Culture and Information Center, whose director was, as ever, proudly on hand to show solidarity with the living Jewish community.

◊

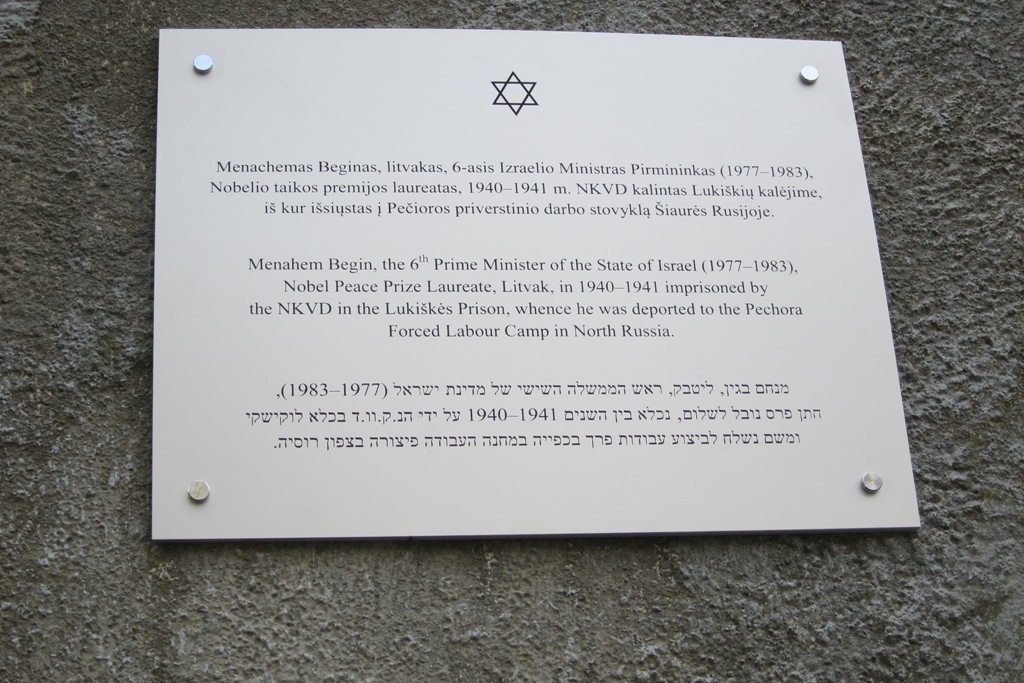

Earlier, Menachem Begin Plaque Inaugurated at Vilnius Jail in Typical Attempt to Deal With Soviet Crimes on the Same Day as Shoah Commemoration

But this was in one sense Part Two. Earlier today, Lithuanian and Israeli officials unveiled a plaque on the wall of Lukishkes Prison in central Vilnius marking the 1940 imprisonment there of Menachem Begin, Israel’s sixth prime minister. The justice minister, Remigijus Šimašius (at left of photo, in gray suit), honored the event with his presence.

Mr. Šimašius has yet to retract his 2009 remarks effectively denying the extent of local collaboration and trying to deflect blame onto the United States and other Western powers. In response, World Jewish Congress president Ronald Lauder said the minister’s statements were “disingenuous” and “totally misleading and unacceptable.”

Moreover, the justice minister has yet to publicly comment on the now six-and-a-half year old campaign by his own prosecutors to defame Holocaust survivors (a campaign that has cost Lithuania dearly in international good will). Would a nice public letter of apology and respect for life achievement to Yitzhak Arad, Fania Yocheles Brantsovsky, Rachel Margolis and Joseph Melamed really be too much to ask?

Incidentally, two of Mr. Šimašius’s prosecutors’ targets, Arad and Melamed, are veterans of Israel’s 1948 War of Independence.

What would Menachem Begin think about that, and about this particular justice minister, who presides over these kangaroo investigations, being on hand to inaugurate the Begin plaque on the jailhouse wall?

Moreover, the new plaque unveiled today, bizarrely pegged to a prison wall, curiously calls Begin a Litvak (his native Brest is on the Jewish border of Ukrainian and Lithuanian Yiddish; his family can perhaps recall whether he considered himself a Litvak as per the plaque put on a prison wall in Vilnius in 2012). Its unveiling today of all days seemed yet another effort to shift focus to Soviet crimes, to the glory of Litvaks of old (in some general “usable past” PR sense) and away from anything that could add to understanding of the Holocaust in Eastern Europe. Government instrumentalization of the Litvak label has been a growing ethnic identity-theft issue for a number of years now.

The plaque on the prison wall about “Menachemas Beginas, litvakas”

In fact, the Soviets released Begin a year later, under the terms of the 1941 Sikorski–Mayski agreement, enabling his migration to the Land of Israel and subsequent pivotal role in the history of the new state.

By contrast, Begin’s immediate family back in Brest were all murdered by the Nazis and their local collaborators at the Bronaya Gora mass murder site. No equivalence. No symmetry. No Double Genocide.

Jailhouse Rock: A few hours later, when the diplomatic glitter had dissipated, the prison wall plaque for Menachem Begin seemed even more out of place.

As one survivor put it today, “From Menachem Begin in a Soviet prison to the latest news from Iran, it’s amazing what they come up with to talk about anything and everything but the Lithuanian Holocaust on the day of remembrance for the Lithuanian Holocaust.”

Elderly survivors in the crowd did not forget Rokhl Margolis or Yitzhak Arad. For them the attempt to turn Holocaust survivors into criminals, in effect for the crime of surviving, while the same government invests heavily in glorifying local perpetrators (considered “anti-Soviet heroes”) is just too much to swallow.

One comment had a particular sting: “Sure, we know the Lithuanian government’s box of tricks, games and commissions about the Holocaust. But we expected the State of Israel to be more loyal to its own citizens.”