O P I N I O N

by Julius Norwilla

◊

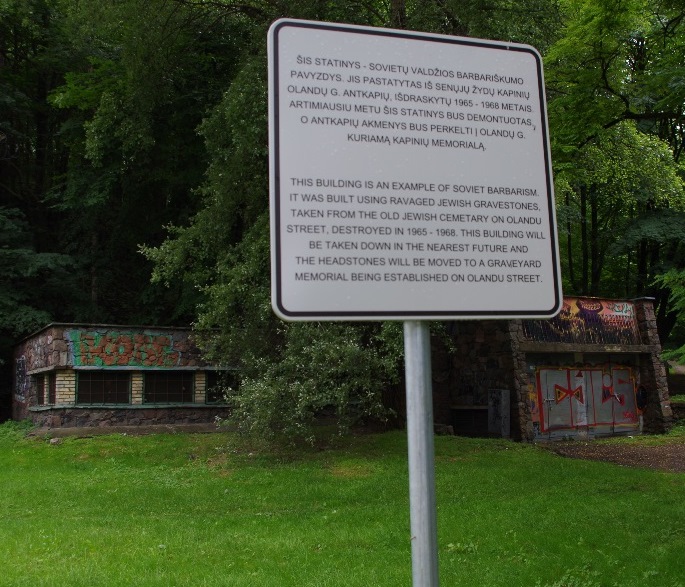

Back in May, the story broke about an electrical station on an uninhabited hillside by a highway here in the Lithuanian capital, Vilnius, being made out of pilfered old Jewish gravestones. It quickly spread to the international press, including London’s Daily Mail. The city’s recently elected mayor, Remigijus Šimašius reacted with lightning speed, getting the city’s sign-making maestros to create and mount a handsome solid-metal smartly round-edged bilingual sign condemning the “example of Soviet barbarism” and promising the rapid removal of the stones to a place of dignity where they will form part of a memorial. A PR disaster was spun into a rapid reaction force’s PR triumph against discrimination that could only do our great city proud.

Photo: Julius Norwilla

All very well, but what about the similar issues that have not made it into the Daily Mail?

For example, what does the mayor think of the new project to erect a twenty-five million dollar convention center in the heart of the old Jewish cemetery at Piramónt, at the abandoned “barbaric” Soviet-built sports center in Šnipiškės, surrounded by and held up by perhaps tens of thousands of graves of Jewish residents of the city? Their gravestones were barbarically pilfered by Soviet authorities but at least many of their remains are preserved intact under the earth of old Vilna precisely where they were laid to rest. Indeed, those small individual graves were honorably purchased by hard-earned savings over some five hundred years of our city’s history. Will our new mayor now be moved to respond to his constituent Pinchos Fridberg, a Vilnius-born, Vilnius-resident Holocaust survivor who suggested in a recent Times of Israel op-ed that “it is a bad idea for our old cemetery to be the foundation for a convention center where people will be cheering, dancing, jumping, singing, and drinking in the convention center’s bars.”

And what does the mayor think about the dozens of places in Vilnius where pilfered matséyves (Yiddish for Jewish gravestones) are built into every kind of architectural edifice, including schoolyards and even the steps to a city-center church (see my earlier article on that ongoing genre of barbarism).

But we live in times where the media can drive the precise focus. Following the report in the capital’s top daily, Lietuvos rytas by Artūras Jančys on 2 July 2015, about a municipality-financed storehouse for reclaimed Jewish gravestones on the grounds of a privately owned plant-and-tree nursery in northeastern Vilnius, a small team from Defending History rushed to inspect the site. Indeed, on Ateities Street, on the property of the excellent “Vilniaus žaluma” nursery we immediately saw the piles of hundreds of matséyves. In early July, the flora there is so vibrant and climbing that the stone dump readily provided me a mental image of ancient Angkor Wat or the Mayan pyramids. A few stones carry readable Jewish characters facing outward, and of course we didn’t turn any over or otherwise disturb the pile, that frankly seemed to be thrown together without the least bit of care or respect (and some were seemingly smashed in the process). The pile is up to 1.5 meters high and is interspersed with trees, bushes, and some tires, wooden landscape framing and other garden house junk.

The soil in Lithuania is black earth or sand, excellent for plant life, but with little stone of construction quality. Stone for construction often needed to be imported from Poland, Sweden, Ukraine or further afield. Over the centuries, fine stonework such as for gravestones for loved ones of any faith or community required great expense for the loving family members of the departed.

In the fifties and sixties, the Soviets liquidated the historical Jewish cemeteries of Vílne, as the city is called in Yiddish, and bulldozers pushed the matséyves away to make the space for new city development. Instead of importing new stone for various municipal construction works, local authorities preferred to scratch out or place facing away from view the layer carrying burial inscriptions, yielding these excellent “free” building stones.

With the declaration of our national independence in 1990 and over the early years of state building, the public cases of desecration of matséyves were rightly condemned as culturally barbaric. In 1992, the (in)famous steps to the Soviet Labor Palace, all pilfered matséyves, were duly removed. It seems they landed here on the grounds of the nursery. But it seems there was no plan of what to do with them, and almost a quarter century later they are lying in a weird heap eerily viewable by those who covet a bush for their garden or an exotic plant for their apartment.

The Lietuvos rytas report informs readers that the municipality is about to move the stones from there, but without details of where or to what purpose. Well, here’s a suggestion based on the idea that philosophical and theological reflection can help provide ready solutions to reversing and making good past profanation.

Instead of just using the matséyves as a political football to put up fancy bilingual signs about Soviet barbarism, a project could be initiated whereby all the lost-and-found Jewish gravestones of Vilnius would be taken to the grounds of the old Jewish cemetery at Piramónt and erected there as a permanent memorial to all those thousands of people who were buried there. Instead of a convention center where people will dance, clap, cheer and visit washrooms on their graves.

Photo: Julius Norwilla

Photo: Julius Norwilla

Photo: Julius Norwilla

Photo: Julius Norwilla