OPINION | VILNIUS | OLD VILNA JEWISH CEMETERY | CEMETERIES | LITVAK AFFAIRS

◊

by Julius Norwilla (Vilnius)

◊

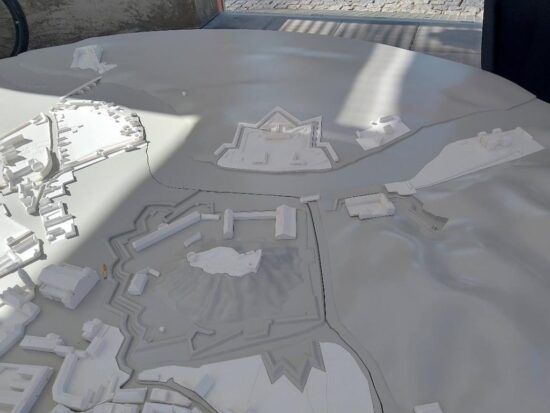

Model of 19th century Vilna: Russian citadel — there. Old Jewish cemetery — not there. Just empty moonscape.

VILNIUS—Last month, the major Baltic news service BNS reported that a dynamic new outdoor exhibition, called “Pavilion: Vilnius 200 Years Ago” would open at the National Museum of Lithuania. Indeed, a handsome new webpage on the museum’s website gives more detail.

A model (“maquette”) of the city two hundred years ago is now to be enjoyed at the foot of Gediminas’s Hill, in the square right in front of the museum. The scale model is based on Imperial Russia’s 1830s plans for the development of the city after the suppression of the 1830 uprising, known as the November Uprising.

But instead of the half-millennium old Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery (at Piramónt, in the district right across the river called Šnipiškės, Yiddish Shnípeshok), on the right bank of the Neris River (the Viliya), in front of Gediminas’s castle mount, there is a disproportionately large citadel. The huge cemetery and its numerous mini-housletsare not marked at all. The citadel of the imperial Russian army is the largest and perhaps the most prominent object in the entire layout.

That citadel was not built to defend the city and its inhabitants from destruction by external enemies. On the contrary, the citadel was designed to keep the city in tight grip and the inhabitants in constant fear. Cannon barrels were pointed at the center of town! In the event of resistance in the city, Russian artillerymen are ready to destroy the city. In other words, to turn a European city of Baroque churches and many synagogues are conceptually regared as a kind of Russian prison. The inhabitants of the city must not forget who rules here. They should stop dreaming of the European way of life of previous generations and forget about independence from the Russian Empire, and accept that instead of personal freedoms, they and their children will live in fear and humiliation.

The current Kremlin warmongers, eager to replicate the victorious campaigns of the imperial Russian army centuries ago, would undoubtedly be delighted by this scale model of urban reconstruction.

But why does our modern Vilnius, celebrating its 700th anniversary, need such a city reconstruction now, especially one that replicates the intentional distortions of the nineteenth century czarist stooges in charge of the city, which does not even bother to include the the world renowned Old Vilna Jewish Cemetery, most of which was left intact even after the forced “sale” of a portion to the Russian authorities for their citadel?

Without ascribing any ill will to the producers of the scale model, we can nevertheless approach them with this proposition: While exposing the imperial Russian view of “the Vilna desired,” a modern scale model must not replicate the occupiers’ desire to wipe off the map the sacred city-center testament to half a millennium of Jewish life, extraordinary creativity and history of Jewish Vilna.