O P I N I O N / F I L M R E V I E W

by Milan Chersonski

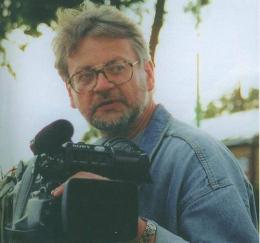

Vilnius film director Saulius Berzhinis

There has recently been extensive Lithuanian media coverage of a conflict between the authorities of the city Jurbarkas, Lithuania, and the film company Filmų Kopa, founded by film director Saulius Berzhinis (Beržinis) and managed by Ona Biveinienė.

To mark the seventieth anniversary of the beginning of World War II in Lithuania and the beginning of the total annihilation of its Jews, the Jurbarkas regional museum commissioned a documentary about Jews who lived in the town before World War II, paid for by the Ministry of Culture and the budget of the municipality. Filmų Kopa was awarded the commission and made a documentary called “When Yiddish was Heard in Jurbarkas.” The town’s name in Yiddish is Yúrberik or Yúrburg.

As the film has become a matter of sharp conflict, it is worthwhile in the first instance to take a good look at the actual product that Filmų Kopa delivered to the residents of Jurbarkas.

Obeliai (Abél), Zarasai (Nay-Aleksánder), Anykščiai (Aníksht), Tauragė (Távrik), Molėtai (Malát)… Somewhere far away in the background we hear a quire singing, and on the screen the names of Lithuanian shtetls (Yiddish shtétlakh) pass by, inscribed in Hebrew and Lithuanian on the stone walls of the Communities Valley at the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem. The announcer’s voice lists the names of shtetls softly and solemnly.

What Lithuanian heart won’t perk up with love and nostalgia at the mention of names dear and familiar from childhood days, places where you were born and grew up, where your nearest and dearest lived for centuries! What Litvak’s heart won’t wring with nostalgia, sharp pain and sadness when remembering these names. For Jews every name of a shtetl now refers to a ravaged, neglected and overgrown Jewish cemetery, houses left abandoned forever by their rightful owners during the Holocaust, and — far more shocking — 20-30-meter-long grave mounds, near the shtetl or in forest clearings, mounds under which lie the remains of the people who, until June 22, 1941, had been citizens of Lithuania, enjoying full civil rights, who were born and lived in these very places.

Berzhinis’s documentary about life and death of the Jews of Jurbarkas is called “Kai apie Jurbarką skambejo jidiš” in Lithuanian (“When Yiddish was heard in Jurbarkas”). The announcer recalls slowly and softly when and how Jews came from the west to Jurbarkas, how they received permission to live here, how they settled in this new place fully and for all time. Jewish people are not nomads. Six centuries ago they settled here and were confident their descendants would live in the same place, and they did.

By the rhythm of the narration the sections of the film pass by. Ordinary life goes on peacefully. Jews were skillful craftsmen and merchants and enjoyed long-established contacts with the local population, new streets appeared, the town grew, and Jews became an integral and indivisible part of the town.

Or so it seemed to them. They didn’t imagine that they were living on top of a volcano that could erupt at any time. The reality was ferociously violent to the Jews. Which of them could ever imagine that at one point all of them, from the very oldest to newborn babies, would be ferociously shot and hurled into the ground, dead or wounded, by their own neighbors, and that then the life of the town would then go on as if nothing had happened, only now, without them?!

The narrator says: “Jurbarkas, conveniently situated for trade and crafts, attracted Jews. Which Lithuanian shtetl could do without Jews? Jurbarkas couldn’t any more than any other. It became a real city with the help of Jews.”

At the beginning of the seventeenth century, especially after Jurbarkas received its Magdeburg rights, its Jewish community became numerous and influential. On September 9th, 1642, Jews received “the privilege” and got the opportunity to all civil rights: to buy land and build houses on it. City streets appeared and the main street, Kaunas Street (Kóvner gas in Yiddish) was built. Residential quarters sprang up, as well as an unusually beautiful synagogue, and a Jewish cemetery was established and tended to for centuries.

The history of the city and its Jewish community passes before the eyes of the viewer. By the middle of the nineteenth century there were no crafts or specialties needed by the citizens that had not been mastered by the local Jewish citizens. From 1918 to 1920 Jews courageously fought in the struggle for Lithuanian independence.

◊

A new episode: the viewer is introduced to a beautiful young woman in the very old Jewish cemetery. She is the current Jurbarkas resident Rita Mažeikaitė. As she tells it, the mysterious world of the Jewish cemetery has attracted her since childhood. She liked to come to this quiet corner of the city and read books, surrounded by the silence. After finishing high school she studied psychology at Vilnius University. Once she came across an advertisement for Jews planning to move to Israel to attend a free Hebrew course. She enrolled in the Hebrew course, although she was a Lithuanian who didn’t plan to move from her native Jurbarkas. She didn’t know herself why she needed Hebrew, but somehow knew that she certainly did need it, and studied it comprehensively.

Image from the film: Rita Mažeikaitė

After returning home, Rita tried to read the inscription on one gravestone. And she did it! So her old dream came true, to read what was written on the gravestones about the people buried in the cemetery in her town. She read in some cases short accounts of their lives with the help of these gravestones. Next, she decided to put the old cemetery in order and restore the gravestones.

There is endless work at the cemetery, but Rita keeps at it persistently. Why? Because this is the history of her city. Rita puts it like this in the film:

“After all, these are not only Jewish gravestones, these are my city’s gravestones. If I can’t express my respect for the people who built our city in any other way, I will do it as I am able.”

For many years now she has been tending and restoring the gravestones, untouched by human hands since World War II. There are perhaps more than 220 cemeteries such as this one in the country, but Rita Mažeikaitė is the only person in Lithuania (and perhaps in Europe) who devotes her free time to the restoration of a deserted Jewish cemetery.

Jurbarkas is a small town where Lithuanians and Jews mixed and mingled all the time. Now the elder cultured people remember with nostalgia the irreplaceable pre-war period “when Yiddish was heard round about Jurbarkas.”

Two natives of the town, Aldona Ogorodnikova and Irena Černiavičienė recollect the names of their Jewish acquaintances, their classmates, and go over the details of their lives and relationships. They were friendly, always attentive to their neighbors’ requests, lent money without demanding guarantees or interest, and were always ready to help in whatever way they could. The old women remember that the Jews knew Lithuanian very well and paid a lot of attention to their children’s education, they strove for Jewish children to know the language of the people among whom they would live their entire lives, and never regretted spending money on education.

◊

Against the background of a song performed by the founder of Lithuanian variety music, Daniel Dolskis (Dolski), the sights of pre-war Jurbarkas appear. There are group pictures of members of Jewish organizations; such organizations were very popular during the two decades between the wars. Historical cinema chronicles about Jewish professional activities and modern episodes alternate, bringing events closer to home for the audience.

A modern play about the Jews who once lived here is shown in the theatre. The passion on the stage is palpable and the actors are playing their parts splendidly. Lithuanian is heard from the stage, because, as is well known, the language of the Jews died here seventy years ago. It was killed in July 1941 in pits filled with warm blood. Their Yiddish language was gruesomely transformed into the moans and cries of inhuman despair, the pain and suffering of those who had been executed but were not yet “fully dead.”

Yiddish stopped being heard in Jurbarkas suddenly, in the summer of 1941, because it was the language of a people who were murdered, mercilessly torn to pieces, although they were innocent and had lived there for ages, never hurting anyone.

The main role is played by actress Lijana Kriaučiūnienė. When she was born there were already no Jews left in Jurbarkas. Liana tells the viewer how she worked with the part, how much love toward the Jewish girl, purity of soul and understanding she put into the role she is playing. The actor Alvydas Šimaitis saw Jews in his childhood and speaks fondly of how he remembers them. The play’s director, Danutė Samienė explains how the play about Jews excited her, and how she worked on the performance.

Retired teacher Vladas Andrikis remembers how before the war on Friday evenings the Jews who lived nearby used to ask him, a schoolboy, to light the Sabbath candles, and always paid him five cents, a hefty sum for a boy in those times. From those faraway years of childhood he remembers how many local people, both Jews and Lithuanians, used to throw coins into the pit dug for the foundation of a city monument.

The young people who became brutal murderers didn’t realize that they were not just murdering living people, Jews and Lithuanians, but their own future. After exterminating the people, they robbed their houses and stole their belongings, still incognizant that the stolen property belonging to the people murdered in their town would not bring happiness to them or their children.

Image from the film: monument to Vytautas the Great, by sculptor Vincas Grybas

Soon, as if springing up from the coins tossed into the ground, a monument to the Lithuanian Grand Duke Vytautas the Great rises up, becoming a classical work of modern Lithuanian sculpture. Its creator, the renowned Lithuanian sculptor Vincas Grybas was among those shot by the “friendly forces”: the local killers. Andrikis’s brother was also among the Lithuanian anti-fascists who were murdered by the same “Jew-shooters” whose victims were mostly but not only Jewish.

In the eighteenth minute of the film a long episode of historical newsreel is shown. To bombastic military marching music Nazi troops are entering the town while locals greet them joyfully with flowers. The streets are decorated with Lithuanian tricolors and Nazi flags. Within a couple of days the Lithuanian flag would disappear for forty-eight years. And as it was in Jurbarkas, so was it throughout Lithuania.

Elderly viewers who haven’t succumbed to the poison of antisemitic propaganda and who know the history of Lithuania, not from modern textbooks, but from their own experience, from their parents’ stories or thorough historical research, know that the “uprising” against Soviet power was prepared by the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) which was founded under the supervision of Nazi intelligence agencies in Berlin. Local LAF cells distributed leaflets calling upon the Lithuanian public to receive the German army warmly.

LAF “government” representative Leonas Prapuolenis addressed the Lithuanian people over Kaunas radio on behalf of the “Provisional Government of Lithuania,” which declared itself the legal government on June 23, 1941, with Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis as its prime minister.

◊

The objections by the present administration of Jurbarkas over the film “When Yiddish Was Heard in Jurbarkas” are in no way a result of deficiencies in the professional quality of the film. Saulius Berzhinis is one of the most distinguished modern Lithuanian documentary film directors, director of some forty documentaries, winner of national and international prizes, and his name is on the list of forty directors who through their creative work promoted the destruction of the Soviet empire. In 2004 he was awarded the title Man of Tolerance. Of course, talented people do sometimes produce a failure, but in this specific case the issue is not about the creative or professional merits of the film.

Representatives of the city’s municipality are demanding that the director interpret certain sections in the film about the history of Lithuania from 1939 to 1990 as primitively and incorrectly as Lithuanian school textbooks are prone to do. The participation by white-armbanders and other Nazi collaborators in the annihilation of Lithuanian Jewry is one issue which the school books address only briefly and casually. There are also serious distortions in explaining the role of Lithuanians in “The Final Solution to the Jewish Question” in historical works by some Lithuanian historians. It is apparent through their domestic policy that the governing elite want to justify the large-scale Lithuanian collaboration with the Nazi regime during World War II.

◊

Jurbarkas residents A. Ogorodnikova and I. Černiavičienė remember the Nazis capturing a Jewish boy and girl and forcing them to show them the houses of Jews. The Nazis walked along the street and painted six-point stars with oil paint on houses belonging to Jews. On the sun blinds they painted them inside and out so it would be seen always (when sun blinds were either opened or closed). The women’s story is combined with the frames of newsreel footage. Apparently, there was something similar to Kristallnacht in Jurbarkas, too.

Against the background of the sad Yiddish song, Shtíler, shtíler, lómir shváygn (“Quiet, quiet, let’s keep silent…”) a photograph from Soviet times appears on the screen: six Jews are standing at an obelisk at the murder site. One thousand two-hundred and twenty-two (1,222) Jews of Jurbarkas were killed here. These six standing at the monument are the only Jews who survived.

The song Shtíler, shtíler connects the visual composition: the obelisk commemorating those murdered in Jurbarkas with the Wall of Honor at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem. Nine-hundred and sixteen names of Lithuanian Righteous Among the Nations (righteous gentiles) are inscribed in the rock of the Wall of Honor. These people risked their own lives and that of their family members to save Jews from otherwise inescapable death. The Lithuanian names and surnames appear across the screen before the eyes of the viewer: Petronelė and Jonas Zaronas; Petronelė and Bronius Beleckas; Petronelė, Ona, Dominikas and Pranas Toliuša; Jonas Gudavičius; Pranas Švestis; Bronislava and Izidorius Paulauskas… In some cases the names are accompanied by photos of the rescuers. In other cases there are only names.

Berzhinis’s documentary accurately describes the time when Yiddish was heard in and all around Jurbarkas, based on historical documents, photos, historical and modern reminiscences and testimonies. The film lasts forty minutes, stirring up uneasy feelings and thoughts about the tragic pages in Lithuanian history, and about its present.

◊

After watching the film, the head of the culture department at Jurbarkas city hall, Daura Gedraitienė, referring to the opinion of members of the commission for forging the city image (there are even such commissions!), with the lack of ceremoniousness characteristic of certain bureaucrats, stated,

“We thought we were buying a film, but we ended up buying a pig in a poke” [in the original: a cat in a sack, i.e. something purchased sight-unseen — Trans.].

Full translation of article available here

If Gedraitienė intended to insult the director, she succeeded without a doubt. But this was just the beginning. An assessment was made that resembles more closely a verdict of guilty in a trial of an accused: “The film not only does not encourage love of Lithuania, it distinctly parts with historical truth.”

This is quite surprising. How is it that officials know the only correct “historical truth,” a truth that they so jealously guard and propagate?

Not so long ago when Lithuania was part of the USSR, formulas such as “the film doesn’t give rise to love for the motherland,” “the film distorts historical truth about Soviet reality,” “the film slanders the Soviet government and Soviet people engaged in building communism,” and the like were often heard coming out of many administrative buildings, from those of collective farm leaders, from ministers of culture, all the way to the secretary-general of the Central Committee of the Communist Party.

In those Soviet days there were many such officers called “art critics in civies,” i.e., they were employees of state security organs, Communist-Soviet supervisors of creative people. They acted without ceremony with artistic and creative workers: if, in their opinion, a film “distorted historical truth,” “slandered the Soviet people, the builders of Communism,” etc., the film was either destroyed outright, or — the preferred method — put on the shelf along with those banned from public consumption. The fate of makers of these kinds of films was tragic. They were at the very least subject to severe repressions and for many years barred from working in their profession.

So how did it come about that in today’s independent Lithuania, politicians and administrators interfere in the work of historical researchers, and decide how these or other historical documents, periods and events, historical figures and events are to be judged and conveyed, in scholarship, education, or art? At times these officials, exceeding the bounds of their authority not only by ordering the creation of art works, also assume the right on behalf of the people to judge them and reject them if they don’t suite the right “image.”

◊

Andrikis, who is 88, testifies on screen:

“Jurbarkas’s death squad was made up of white-armbanders, members of the Riflemen’s Union members [a paramilitary organization in pre-war Lithuania – Trans.] and the police whose chief was phys-ed teacher Mikolas Levickas, my former teacher. Police, riflemen and white-armbanders under M. Levickas’s command caught the Jews and others who were doomed to death, arrested them and killed them. […] There was Romka Levickas, and his brother, rifleman Vincas Ausiukaitis, Engelaika, Pranas Bakus, Almonaitis, policeman Krengelis, Urbonas, Kriščiūnas, Martinkus, Nivis and others. And the Hitlerites [i.e. Germans] didn’t shoot there, they just filmed and took photos, but didn’t take part themselves. The Lithuanians managed it all on their own.”

Image from the film: some of the white-armbanders in Jurbarkas

The fact that Andrikis, a Communist in Soviet times, took part in the film especially irritates representatives of the Jurbarkas administration. They complain that Andrikis names the names of the murderers in “the tone of a prosecutor.” Apparently they feel that one should speak of murderers in a different tone…

Speaking for the city administration, Daura Gedraitienė declared:

“The Lithuanians in this film are called Jew-shooters (žydšaudžiai). Not directly, but by naming those who shot by name, though historical documents show that the execution was organized not by the Jurbarkas police or the Jurbarkas riflemen, but was carried out by the Tilsit [town in East Prussia, now Sovetsk in Kaliningrad oblast in the Russian Federation – Trans.] SS detachment located in town. It was the Germans’ work. Since the film was made with the state’s money, it seems to me we shouldn’t show it to an audience, because it has become an anti-state film.”

Although nobody accuses the Lithuanian people of anything, and doesn’t call them murderers, the chief of the city’s culture department uses a tired and hackneyed technique: she is attempting to suppress names of the specific perpetrators named in the film by equating them with the whole of the Lithuanian people, a tactic or goal not apparent in any part of the film under discussion.

Upon hearing the accusation that he is the author of an anti-state film, Berzhinis countered that he had checked all the names appearing in the film in the Lithuanian Special Archive and in authoritative published academic works. To preclude further speculation on this topic, he put full sources of historical works and archive documents confirming the names named in Andrikis’s testimony as text on the screen right above the moving images.

The Regional Jurbarkas history museum employee Adelė Meizeraitienė said after viewing the film:

“Whether someone likes it or not, we’ll keep the film, just as we keep other exhibits. Museum staff don’t belong to any particular political party and are not engaged in carrying out the decisions of any party. If they continue to accuse us of having ordered a film against Lithuania, we’ll ask the Ministry of Culture to evaluate the film’s artistic merits.”

This museum employee’s words have the ring of professional dignity, of someone who knows and loves their profession. They introduce museum visitors to the history of their own town and its people, who have built the town over the centuries. The Nazis invaded this country and this town, awakening the most violent and base instincts of thousands of Levickases who became monsters; they inflicted irreparable harm on Jews, on their own homeland and on their people. It is so very reprehensible that protectors of these monsters appear under the guise of supposed public servants.

We should offer special thanks to the staff of that museum for making sure the film “When Yiddish Was Heard in Jurbarkas” isn’t gathering dust on a shelf, that is being shown to the people for whom it was intended. They are doing the work of education among the people of Jurbarkas courageously. It has long been necessary to tell the truth about the genocide that was perpetrated in Lithuania and to name the names of the local perpetrators of Hitler’s plan for the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question.”

On 3 July 2012, the anniversary of the murder of 1,222 Jews of Jurbarkas, museum employees intend to show the film all day, non-stop, in commemoration of the residents of the town who were brutally tortured to death and murdered.

◊

What will happen now? Will the public of the town and of Lithuania continue to blame the annihilation of the Jewish community on foreigners and the Jews themselves, or will they come to understand the bitter — but absolutely necessary, for the country and its people — truth, which continues to be suppressed, but even worse, also adorned, turning murderers into martyrs and heroes and “freedom fighters”?

All of Jurbarkas’s media, print and webpages discussed Berzhinis’s film. The national newspaper Lietuvos rytas also published an article called “The Bloody Jewish History: Like Salt in the Wound” by Erika Baronaitė. None of the articles expressed any complaint or criticism concerning the professional quality of the film.

Many comments by readers appeared on webpages dedicated to news in Jurbarkas, but Baronaitė’s article attracted the most. I would like to cite one, comment number 537, signed by “Rasa”:

“I feel deep pity for those commentators who think Berzhinis demonized Lithuania. The demonizers are those of you who demonize it with your stupid comments. The director only showed the facts in his film. Is it not a fact that some Lithuanians voluntarily took part in the killing of Jews? Instead of admitting this cruel fact and condemning the criminals, you seek justifications. Did Jewish children have to die because some of their parents served in the NKVD? Weren’t there also Russians and Lithuanians in the NKVD? According to you, the heads of Russian and Lithuanian children had to be smashed with rifle butts, too? Wake up. Let’s at last become honest people who condemn their murderers and take pride in their heroes.”

Translated from the original Russian by Ludmilla Makedonskaya (Grodno). Edited by Geoff Vasil. This English translation has been approved by the author.

OTHER ARTICLES BY MILAN CHERSONSKI