E V E N T S / O P I N I O N

by Defending History Staff

VILNIUS—For many years it has been a source of deep pain to many Lithuanians, Jews and others that the capital (and cities and towns around the country) continue to have street names honoring Holocaust perpetrators and collaborators but none for the true heroes of the Lithuanian Holocaust — the Lithuanian rescuers, who risked their and their families’ lives to “just do the right thing” and rescue some person or persons of a minority marked for rapid murder on the basis of Jewish birth. In the Baltics, the rescuers had to have much more courage even than in many other countries, because they were regarded as enemies of nationalist patriotism, as then constructed, not only as defiers of the German occupying forces’ program of extermination. They were regarded here as “enemies of Lithuania” (or Latvia, or Estonia), and sympathizes of communism who could expect no mercy if found out either by the German authorities or the local Lithuanian forces.

In 2013, Defending History objected to the plan to name a street for Ona Šimaitė in the boondocks and pressed for her street to be right in the city center.

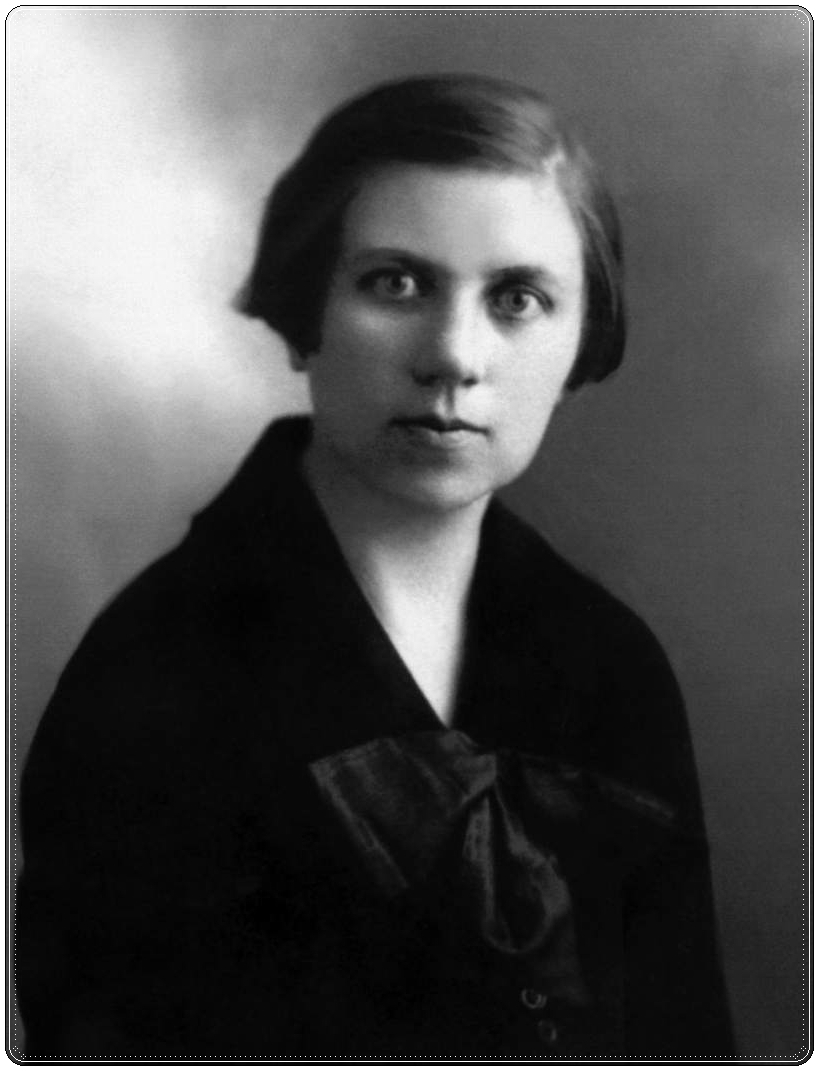

It was therefore with a feeling of genuine exhilaration that on Tuesday, 22 September, a modest-sized group came to see the dashing, handsome new young mayor of Vilnius, Remigijus Šimašius launch the new street name Šimaitės gatvė (Shimaite Street) in honor of the inspiringly courageous Vilnius University librarian, Ona Šimaitė (often known in the war years as Anna) who rescued numerous Jews from the Vilna Ghetto. She arranged for their rescue by other righteous people, smuggled children to the safety of Christian foster homes in town, arranged for the forging of identity documents, and helped smuggle provisions into the Vilna Ghetto as well as carrying letters between ghetto inmates and residents of the city outside the ghetto gates. Her life has come to new and deserved attention thanks to Professor Julija Šukys’s important book, Epistolophilia: Writing the Life of Ona Šimaitė.

The mayor spoke eloquently and with precision and gave his listeners much reason to hope that this is the start of a new and inspiring chapter in the history of one of the culturally great multicultural cities of Europe. Elected only last spring, he is seen to have a grand opportunity to change things in a big way, independently of various national-level government bodies, particularly those constituting the local Holocaust Obfuscation industry, as it is often called.

Vinius mayor Remigijus Šimašius launched the city’s Shimaite Street. Photo: Julia Rets for DefendingHistory.com.

Šimaitė (1894 – 1970) was betrayed and arrested during the war’s last months in 1944. She was tortured by the Gestapo, but saved from execution by the intervention of the head of Vilnius University’s library. She was sent to Dachau, survived the war, and settled in France for the remainder of her life, except for several years in the new State of Israel in the 1950s. In 1966, she was named Righteous of the Nations by Yad Vashem. It is difficult in all of Vilnius’s wartime history, to find many more who did even a fraction of what this one incredible woman achieved for humanity in Lithuania’s historic capital, something that should be much more central in the city’s consciousness, history and image.

Mayor Šimašius graciously turned a new leaf in his city’s history with this first gesture, which has been many years in the making. The proposal for an Ona Šimaitė street name was mooted some years ago, but various of the powers that be designated a street kilometers away from central Vilnius in an outlying area where it would have been quite meaningless for the city’s residents, the nation’s young people, and visitors from around the world. It would have backfired, leading to feelings that “someone doesn’t want this in the center of town.” Defending History (among others) pointed out the inherent flaw in the project, and as happens frequently, played a role, howsoever modest and unacknowledged, in contributing to a wider change in thinking on an issue. It is heartwarming to see such progress in Vilnius. Although not in the very center, the street is a very short distance away, between the popular Bokšto Street (Yiddish Baksht) and the banks of the Vilnelė River (known in Vilna Yiddish as Di Vilénke). It is part of a favored walking route from Užupis (Zarétshe) uphill to the old town center.

◊

In the folklore of many a fine city, a street name or corner that commemorates a famous person can take on a kind of life of its own. Let it be for the blessing of Ona Šimaitė’s place in Vilnius history that several conversations among the Vilnius residents and visitors who had come to see the launch of her street — a bus was organized from Ponár, where the day’s previous event was held — dealt with issues of today and tomorrow.

One set of conversations revolved around the current circumstance that the Jewish world’s eyes are currently on Mayor Šimašius concerning a burning present issue in the heart of his city. Last month, a group of top Litvak rabbis from around the world came to Vilnius to plead with him and other high officials to move the new $25,000,000 convention center project away from the old Jewish cemetery at Piramónt, in the Šnipiškės (Shnípishok) district, where it would cause pain and strife for generations to come and where it would be a permanent scar on the face of Vilnius and the international reputation of Lithuania, all the more painful for having been inflicted by free, democratic EU/NATO Lithuania, not the Soviet occupational authorities of another era.

Vilnius mayor Remigijus Šimašius listens to pleas from several of the group of Litvak rabbis from three continents who came to beseech him last month to move the new convention center project away from the old Jewish cemetery to a new venue where it can do Vilnius proud. There is a mounting international furore over the “convention center in the Jewish cemetery” project.

There are high hopes that the new mayor will stand up to the dodgy property developers, the ultranationalist establishment, and a group of notorious, compromised-to-the-point-of-comedy “grave-trading hasidic rabbis” from London to stop a central Vilnius travesty where thousands will clap, cheer, revel, use bars and toilets atop and surrounded by thousands of Vilna Jewish graves going back to the fifteenth century, this in a city where close to 100% of the city’s Jewish population was massacred in the Holocaust with vast voluntary collaboration from the contemporary Lithuanian nationalist establishment. The international opposition to the “convention center in the Jewish cemetery” is rapidly growing.

As the mayor was speaking, one elderly local Jewish woman at the Ona Šimaitė event cast her gaze down the sloping hill framed on one side by the newly named street for Ona Šimaitė, and on the other by open hill space. After a long hard look she said (in Yiddish), “What a perfect place for that new convention center! The incline for the rows of seats and the perfect spacing have been waiting since before there was a Vílne!”

On another long-standing painful issue, the memorials and street names and plaques honoring Holocaust perpetrators, the mayor last summer received a petition from a group of Lithuanian intellectuals calling for the removal of at least one of the central Vilnius plaques that honor a notorious Holocaust perpetrator. Many hope he will start by calling for removal all the shrines in town to this particular Holocaust perpetrator, J. Noreika, starting with the stone block overlooking Gedimino Boulevard a stone’s throw from the Seimas (parliament).

◊

But within Vilna Jewish lore, the opening of Shimaite Street (as it is already known to the city’s international and diplomatic community) on Tuesday, the eve of Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), holiest day in the Jewish calendar where people ask forgiveness of each other and of God, had another unintended memorable moment. The top of the street and the new Shimaite Street sign is smack opposite Chabad House, the de-facto major religious Jewish community in Vilnius where thousands have come to celebrate Jewish holidays and to receive religious guidance and assistance for family events. Ever since the sensational autumn 2005 court case a decade ago pitting the Jewish Community against Vilnius Chabad, relations between the two have been rocky. A long period of refreshing improvement seemed to be backsliding in recent months with various snide references to the religious group on the main community’s website.

The Chabad rabbi, Rabbi Sholom-Ber Krinsky, who settled in Vilnius twenty-one years ago, and whose track record has not been without its own controversies, has been the city’s only truly full-time resident rabbi for virtually all that time. He and his colleagues were “naturally” not invited to the event, even right in front of his own premises which includes the city’s de-facto second active synagogue that is on many Jewish holidays much better attended than the Choral Synagogue. Last week, in a portent of reconciliation between the communities, on the Jewish new year, the official community’s head of its own religious community, Simas Levinas (Shmuel Levin), himself attended the Chabad celebration that came a day after the eve-of-holiday celebration that he helped direct at the Choral Synagogue.

During the Ona Šimaitė street sign launch, Rabbi Krinsky was rushing with several of his sons to and fro in preparation for the Yom Kippur fast day to start only hours later. But when he saw the gathering he came to shake hands with the mayor and others and to exchange pleasantries. It so happens that for the second year in a row, the Chabad community is having some difficulty in obtaining the necessary city permit for construction of the annual sukkah (Yiddish súke). At some point, it occurred to several of the assembled to use the occasion to approach the mayor to ask for a rapid issuance of the permit for the outside sukkah for the annual Succoth (Súkes) festival, which is beloved of hundreds of Jewish people (and many non-Jewish guests) in today’s Vilnius, but before anyone could make the move, the event was over and the officials had rapidly dispersed. Still, rapid discreet contacts with the mayor’s office in the last few days will hopefully fix everything in time for the sukkah to be up and running by this Sunday’s sundown start to the biblical Feast of Tabernacles.

After the mayor’s speech, the second speaker, who also delivered an excellent talk, was Fania Kukliansky, chairperson of the official Jewish Community of Lithuania. Under the aura of the handsome new street sign designating Shimaite Street, Ms. Kukliansky and Rabbi Krinsky had a conversation in public for the first time in quite a while. It is now hoped that a full reconciliation between the two small but vibrant Jewish communities of twenty-teens Vilnius will come soon.

Faina Kukliansky, chairperson of the Jewish Community of Lithuania since 2013 with Rabbi Sholom-Ber Krinsky, the city’s Chabad rabbi since 1994, at the gathering outside Chabad House for the launch of Ona Shimaite Street in Vilnius by the city’s mayor on 22 September 2015. Photo: DefendingHistory.com.