OPINION | HUMAN RIGHTS | LITHUANIAN-JEWISH RELATIONS | CEMETERIES | OLD VILNA JEWISH CEMETERY | OPPOSITION TO CONVENTION CENTER PROJECT | PETITION

◊

by Andrius Kulikauskas

On July 2, 2018, at 11 AM, Lithuania’s state property bank, Turto Bankas, led an open meeting to discuss the rental terms for the operator of the Vilnius Concert and Sports House, previously known as the Soviet Sports Palace (Sporto rūmai), which the Soviets built on Vilnius’s oldest Jewish cemetery. The search for an operator is part of a plan by the Lithuanian government to remake the decrepit building as a modern convention center and a symbol of Vilnius. According to critics, the plan is senseless and the symbol shameful.

◊

The hourlong meeting at Turto Bankas, Vilnius g. 16, Vilnius, was led by project leader Karolis Maželis and his colleagues. The eleven participants included representatives of UAB Infrastruktūra LT, Seven Entertainment, UAB LITEXPO, the law firm GLIMSTEDT, journalists Julius Norwilla and Andrius Kulikauskas, and concerned citizen Ruta Bloshtein, the organizer of a petition which close to 44,000 people have signed online to respect the cemetery and to build the convention center at another location. Turto Bankas publicized the meeting through its website, along with a draft of the rental terms and answers to comments and suggestions received from interested parties.

At the meeting, Turto Bankas noted its goal of selecting an operator by the end of the year. A separate process is determining the company that would renovate the building. Turto Bankas subsequently announced on July 4 that it will be purchasing an architectural plan for the building’s reconstruction and for oversight of the project. The term “reconstruction” (rekonstrukcija) as opposed to “renovation” (renovacija) goes against the spirit of earlier agreements with the Lithuanian Jewish Community which intended to limit disruption of the grounds around the building which to this day are, in fact, a cemetery. According to a TV3 report on May 7, 2018, reconstruction is scheduled for the start of 2020, and the center should open in 2021. Turto Bankas seeks to rent out the building for a ten year term. The convention center will host up to 2,500 participants in 10 transformable spaces occupying 16,000 square meters. Lithuania does not have companies with the resources to both build and operate such a center.

◊

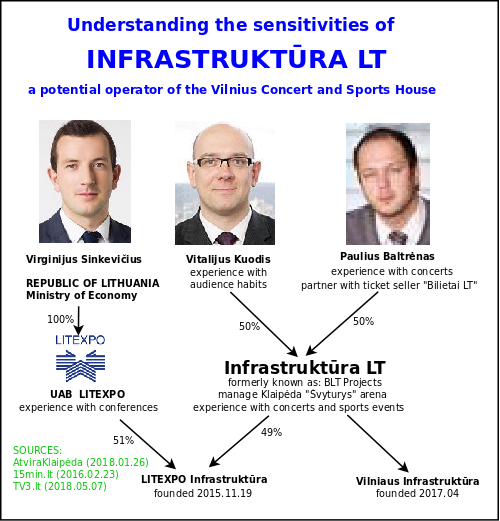

The Lithuanian press, namely TV3 on May 7, 2018 and 15 min on February 23, 2016, has shed some light on those interested to operate the convention center. UAB Infrastruktūra LT, owned by Vitalijus Kuodis and Paulius Baltrėnas, originally teamed up with Lithuania’s state owned UAB Litexpo, which manages a large center for international conferences. However, last year, UAB Infrastruktūra LT set up its own company, Vilniaus Infrastruktūra, for which, apparently, it is seeking foreign partners.

Vitalijus Kuodis of UAB Infrastruktūra LT was most active in the July 2 discussion. He was especially concerned about the article 18.6 in the rental terms, which stipulates that the rentor have executed at least three contracts, within the last three years, as the basis for conducting international conferences in a building that they manage and/or own. An international congress must last at least two days, have at least 500 participants, the speakers must be from other countries and the client must be a foreign entity or the Republic of Lithuania. UAB Infrastruktūra lacks experience serving international conferences and so may look for a foreign partner.

◊

Another question which arose concerned the purchase of equipment by the rentor. Depreciation of such equipment typically is for a period greater than 10 years. Turto Bankas is open to a concession arrangement of at least 15 years. The advantage of a rental agreement is that the rentor could be chosen within the current year, which is to say, before reconstruction is underway. Both Turto bankas and UAB Infrastruktūra LT were curious what the lowest rental price might be, but both declined to offer figures.

◊

◊

Soviet Heritage: Palanga vs. Vilnius

UAB Infrastruktura LT is competing with Seven International, which manages the Siemens Arena in Vilnius. The two companies recently competed for rental of the Palanga Concert Hall, which can be meaningfully compared to the Vilnius Concert and Sports House. UAB Infrastruktūra LT owns UAB Pajūrio infrastruktūra, led by Paulius Baltrėnas, which won the rental agreement and started to manage the center on March 29, 2018. The 2,200 to 3,000 seat concert hall is almost 5,000 sq.m. It will host at least 77 events per year, including classical and pop music, with at least 137,900 attendees per year. Theater performances will be shown for the 550 seats in the parterre. There will also be two bars and perhaps a museum to Lithuanian singers such as Stasys Povilaitis. UAB Pajūrio infrastruktūra will pay 154,000 euros per year to the city of Palanga for the 20 year rights, making a total of 3.1 million euros. The brand new concert hall was opened in 2015 at a total cost of 9.4 million euros, of which 4.4 million were invested by the city of Palanga, 2 million came from Lithuania’s investment program, and 2.9 million from EU structural funds.

The numbers suggest that building a brand new convention center away from the Vilnius cemetery might cost substantially less than immortalizing the Soviet Sports Palace in Vilnius.

◊

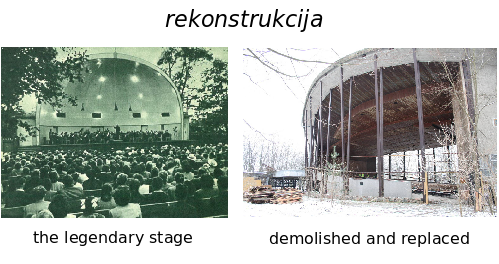

The Palanga Concert Hall also illustrates what “rekonstrukcija” can mean in Lithuanian. The open air “Summer Stage” (Vasaros estrada), which seated 1,200, was built by the Soviets in 1971. This coincided with the completion of the Soviet Sports Palace in Vilnius in 1965-1971, which seated 4,400 spectators. Indeed, both buildings employed the same steel-beam construction. In 2011, the city of Palanga stepped in and took over the “Summer Stage” from Lithuania’s National Philharmonic. The building’s value at the time was 35,000 euros. As reported by Vakarų ekspresas, the city was afraid that the decrepit building would end up with Turto Bankas and get auctioned off to developers, who would inevitably build high-rise apartments at the location. No sign of the “legendary” Summer Stage and its exalted steel-beam construction was left after its “rekonstrukcija”, which is to say, demolition and rebuilding. The public has embraced a completely modern concert hall which is competing to host the European Brass Band Association’s Championship. Any lingering nostalgia for the Soviet stage will be satisfied by a small museum on the premises or perhaps a few photos on the wall.

Meanwhile, Lithuania has placed the Soviet Sports Palace in Vilnius on the registry of national heritage. Which is to say, the registry contradicted itself, by preserving the building which desecrated a Jewish cemetery which is on that same registry. Apparently, Soviet heritage becomes attractive if, like an old rug, it can cover up Lithuanian Jewish heritage, which is not appreciated as it once was and someday might yet be again.

◊

Business Risks in Desecrating a Cemetery

As befits a democracy, participants of the open meeting at Turto Bankas had the opportunity to ask questions about the rental terms. I asked whether the terms would address which party would absorb the various risks involved. For example, the terms require the rentor to organize at least ten international conferences per year. Who assumes responsibility if an international boycott is organized because of the desecrated cemetery? Or if associations simply respect the sensitivities of all of their members? Or if competing venues emphasize that point to their advantage? What if Lithuania’s banks, which are based in the Scandinavian countries, decide not to sponsor conferences there?

◊

What if the Lithuanian government realizes that this particular building speaks against its efforts to attract international conferences in medicine, bioengineering, finance and other areas which may be more sensitive to ethical issues than the current administration, Turto Bankas and the event managers?

And what happens when the Lithuanian government has realized it has made a great mistake? What if US President Trump points to the investment in Soviet heritage as evidence that Lithuania belongs to Putin’s sphere of influence? What if his high-ranking son-in-law Jared Kushner, an American Jew, condemns the building as antisemitic?

◊

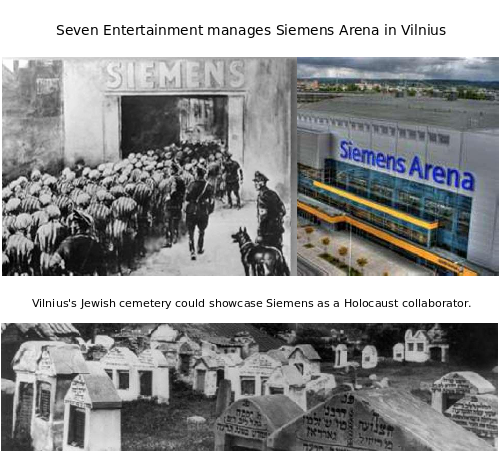

What if a company like Siemens withdraws its name from the Siemens arena because it can’t afford to be tarnished by an event manager’s insensitivity to Jewish concerns?

What if Lithuania runs out of excuses for desecrating the cemetery? What if the Lithuanian Jewish Community elects a new leadership which condemns the building? What if the United Kingdom determines that the only rabbis to approve of Lithuania’s actions, the London-based CPJCE, are corrupt and fraudulent?

What if Lithuania’s state policy of distorting the Holocaust is finally confronted with the truth? What if the world comes to know that so-called anti-Nazi heroes like Jonas Noreika in Telšiai were Holocaust perpetrators? What if the point is made that, in fact, Lithuania is anti-Nazi only to the extent that it cares for Hitler’s greatest victims, the Jews?

◊

What explicitly in the rental terms will ensure that activities respected the sensitivities of religious Jews and all who likewise care?

The representatives of Turto Bankas were visibly moved by the questions but they offered no answers, except to say that they themselves would decide all matters of sensitivity. They also said that a meeting should be arranged with the Administration’s Chancellor.

I also asked whether Turto Bankas was making any effort to measure the spiritual capital of Vilnius’s oldest Jewish cemetery, which if restored as a symbol of empathy for Lithuania’s Jews, might rival the spiritual capital of the Hill of Crosses. I shared the abstract that I will give in Riga, Latvia, on that subject. I also shared a declaration, “In 1,000 years” (Už 1,000 metų).