O P I N I O N

by Evaldas Balčiūnas

◊

The modern Republic of Lithuania has been creating a cult of the partisans. Statues are built to memorialize them. There are commemorative plaques and streets are named after them, as well as schools. One of the most prominent to be hallowed by the cult is Jonas Žemaitis, also called Vytautas, Luke, Matthew, the Silent and general as well as president. His biography is a tapestry of events and adventures. One could write an adventure novel about them, except that… Žemaitis isn’t necessarily a hero.

Some twenty-five years ago only a handful of Soviet security personnel, a few of his comrades who survived and perhaps a few historians knew of this man. He was not known in wider society. Over the course of a quarter of a century, the legend of the man grew from an unknown figure into, at first, the noble leader of the military, then he even became the president. The reasons for this are rather obvious: this person’s comrades, a half century after his death in the Republic of Lithuania, became part of the dominant political force. A source of support for those who wanted to form a foundation out of pre-Soviet Lithuania and the underground who fought the Soviets.

The official version of his biography is certainly heroic:

The lionization of the partisans can be read on the webpage of the so-called Genocide Center:

http://www.genocid.lt/datos/zemaitis.htm

And on the webpage of the Jonas Žemaitis Lithuanian War Academy:

http://www.lka.lt/index.php/lt/194837/

Of course there are few facts in these biographies. They are limited to brief and incomplete details. There is more focus on the partisans and the declaration of February 16, 1949.

http://www.genocid.lt/UserFiles/Image/Muziejus/Virt_parodos/signatarai/20090205_deklaracija.jpg

It is surprising, but this declaration, signed in 1949 and basically forgotten for fifty years, became at around the same time, on January 12, 1999, an icon of “the fight for freedom.” It was recognized as a legal act of significance to Lithuanian statehood and was equated with the February 16, 1918, Lithuanian Declaration of Independence.

To understand how this was achieved, it’s worthwhile quoting several passages from N. Gaškaitė-Žemaitienė’s “monograph” on Jonas Žemaitis. N. Gaškaitė-Žemaitienė is a correspondent of the so-called Genocide Center. Her book is called Žuvusiųjų prezidentas [“President of the Fallen”], published in Vilnius in 2005 by the so-called Genocide Center. It’s worthwhile and all the more so because it speaks to certain principles:

“And nonetheless, there are too few surviving documents and fragments of memoirs to reveal fully not only this noble person, but also that difficult period and its burden. As J. Mockūnas noted, each author fills in the empty spaces in a biography using his own imagination. … This book is no exception.” (pp. 13-14)

Based on this sort of principle, an entire pantheon of heroes has been created. Of course, to lend more contrast and nobility to the picture, the so-called Genocide and Resistance Research Center has tended to omit as well as create facts to add to these imaginary tales…

Efforts at lionization are spoken in the name of all Lithuania. This has been done in turning the adventurer of questionable morality, Jonas Noreika, into “General Vėtra,” about which I’ve written previously. The idea of turning individual partisans into a centralized and legal government is so important to the modern mythmakers that they are not bothered by the fact that the rebels of the 1941 Uprising bear the responsibility for the brutal murder of tens of thousands of their fellow citizens. We even know more about J. Markulis—complicit in the death of several hundred of his fellow partisans whom he turned in to the Soviets—for his efforts to centralize partisan activities than we do about the people he betrayed. The search for whom to assign the spectre of “legitimate” government has made official “historians” blind, and it is all but forgotten how the Soviets exploited this idea, not only in Markulis’s circle, but in those of “General Vėtra” and J. Žemaitis, some of whose formations were led by commanders who went over to the Soviet side.

But let’s leave talk of “betrayal” for another time. Right now, let’s look at what was left out in the making of the legend of Jonas Žemaitis. This is all the easier, since these details are rather striking, and probably don’t seem appropriate for the governmental heroization project, or even contradict it outright. The legend is held together by gossamer threads and it’s only a matter of time before it falls apart.

◊

Žemaitis was a captain when World War II began. He only became a general in a declaration signed by people whose military rank was below his. Fifty years later, on February 14, 1997, the Lithuanian president promoted him to retired general brigadier. The foundation for the making of the legend was laid, and a few years later, on March 11, 2009, the legend was completed with the announcement that Jonas Žemaitis was the fourth president, that came around the same time as various monuments and celebrations.

This adds to the man’s biography which has sufficient twist and turns already. Beginning in childhood. He was born in Palanga to a manor estate servant and modern dairy superintendent. He began school in Lomża, Poland. And if not for the destruction of the World War I and the revolution that toppled the Russian Empire, the future president likely would have become a member of the young Polish bourgeoisie. Because of the ruin and confusion caused by the war, his parents returned to their former home [which was now in Lithuania] and the future president completed six grades at the Raseiniai Gymnasium. The family was not well-off and when he was a young man and was seeking further education, he matriculated at the War Academy in 1926, and was graduated in 1929.

It would appear he left school with more than just a sense of patriotism: he also carried with him pompousness and an inflated ego as an officer. In 1935 the second artillery unit was deployed to Klaipėda. It was at this time that there were court proceedings against Nazis who were agitating in this originally German city, previously called Memel. Relations were strained between the “Žemaitijans” and the Memel-landers. Locals had harsh words for Lithuania and representatives of its government. In May of 1936, either because of an affront to J. Žemaitis’s “dignity” as an officer, demanding total obedience, or perhaps simply due to youthful arrogance, he lost his composure and joined in street-fighting to defend “the honor of an officer,” and got a bullet in the chest. It all ended well, though, and the future president survived. Surgeon Juozas Žemgulys operated on him.

The wound didn’t prevent him from passing his exams and here we have an as-yet unwritten and new turn of events in the novel: Jonas Žemaitis goes to the French artillery academy to improve his skills. He uses the opportunity to improve his French and German skills. The classes pass easily and he has time to travel around, but this change of scene in the biography of the future president has remained without any greater description. Several photographs have survived, but there is nothing exceptional about them. After completing his education and tourism in 1938, our hero returns to Lithuania.

The year of 1940 brought many changes in the life of the nation. Many soldiers retired. Many were arrested. J. Žemaitis seems to have been unaffected by those changes. He successfully pursued a career, now in the Soviet “people’s army.” The captain took an oath to serve the Soviet Union and was appointed director of training for the 617 artillery unit of the 184 division. He prepared he next generation of soldiers in the “people’s army.” Social changes were mirrored in changes to Žemaitis’s personal life: he got married. He married a beauty from Lentvaris named Elena Valionytė. It was an ironic twist of fate that led to his meeting his future wife, for which he must have been thankful to the Soviets for giving Vilnius to Lithuania. Another possible twist in the novel. As with the life story of his son, Laimutis, raised by other people.

◊

In the summer of 1941, Lithuanian units of the People’s Army were stationed at the Pabradė military base. And this is where the war caught up with Žemaitis. Žemaitis didn’t want to tear himself from his mother’s apron strings (or his beloved homeland) and flee east. Canon pulled by horse got stuck in sand, it was hot and difficult. Žemaitis forgot he was a commander and, as the so-called patriotic sources tell it, “consciously remained” and surrendered himself to captivity under the Germans. There are several variations on this story, though. According to one, he did this with a group of soldiers. Another version has it he did this with a group of officers. People with an understanding of legal terminology would simply say “with a group of deserters,” but this is unacceptable to the crafters of this man’s biography, although it is needs to be said. The Lithuanian War Academy is named after a deserter, and as we will see, although this was the first time, it wasn’t the last time Žemaitis ran away from the military.

What sort of traditions does a military academy named after a deserter hold dear? Perhaps the tradition of the pre-war Lithuanian officers corps, renowned for their enormous salaries, military coups d’etat, “patriotic manifestations” and… a real lack of desire to actually do battle with the enemy. It ought to be recalled that the Republic of Lithuania at that time shamefully accepted the ultimata of neighboring states—Poland demanding and receiving the re-opening of diplomatic relations with Lithuania (1938), Nazi Germany’s demand for the return of Klaipėda/Memel (1939) and finally the Soviet Union’s demand for the nullification of national independence (1940). It would be naive to hold out hope the bureaucratic hack writers might admit the existence of such a tradition, but this “twist” in the story can turn any of their writings into real news, or at least it provides a nice needle for letting some of the air out of an over-inflated patriotic balloon.

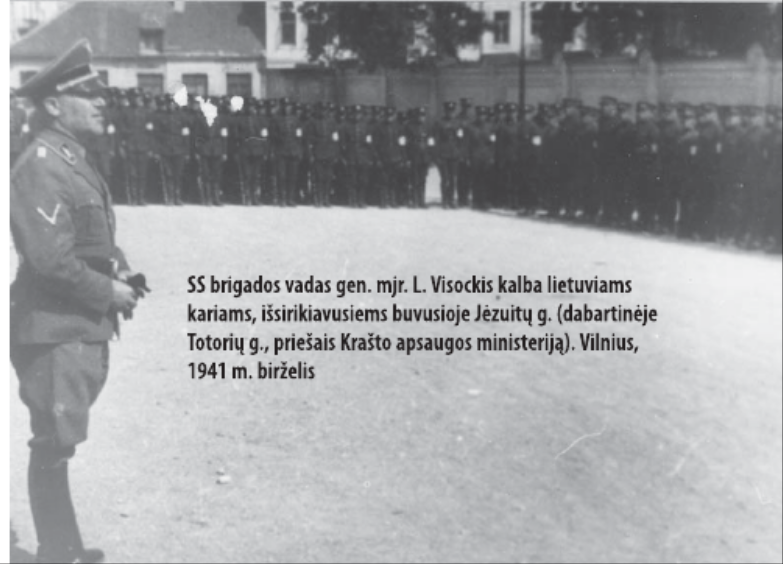

Let’s get back to the story. The deserter or captain known as J. Žemaitis surrendered at Valkininkai on June 24, 1941. [He was at] a prisoners’ camp at the same place until June 29. Then there was a march of Red Army prisoners to a camp in Vilnius. The patriotic version has it that “all Lithuanians were removed to the military facilities on Kalvarijos Street” from that camp. It is known Lithuanians who refused to serve the Nazis were held at POW camps until summer of 1942. I believe those who were moved to those military facilities and their commanders must have agreed to serve the Third Reich. This belief is reflected in the photograph featuring a column of soldiers ready to serve the Reich, before whom stands an SS officer, which seems to have been taken at exactly the place where now stands a pompous column with a bust of Žemaitis on top, right in front of the War Ministry.

Photo is from Kariunas no. 89 (2006), where the caption translates: SS brigadefuehrer maj. gen. L. Visockis addresses Lithuanian soldiers assembled at the former Street of the Jesuits (now Totoriu street, next to the Ministry of National Defense). June, 1941, Vilnius.

The Germans wanted simple and clear agreement:

According to historian A. Bubnys, the oath those agreeing to serve in the Auxiliary Police Battalion took went like this:

“I, upon entering voluntarily the Auxiliary Police Service Battalion for six months and [sic?] in the leadership of the Leader Adolf Hitler of the Great German Reich, creating a New Europe, swear to perform the tasks assigned me conscientiously, to adhere to military discipline, to stand before Military Justice to answer for crimes and transgressions committed during service, to keep secrets sacredly and not to belong to any banned organizations; not to provide any information to enemies, and to report immediately to my superiors anything I learn about them [the enemies].

(Date, signature)”

Even after the period of service ended, however, police battalion troops were compelled to continue. By order of Heinrich Himmler on September 28, 1941, police battalion troops were sworn in to serve for a period of unlimited duration. The procedure for the new oaths was explained in a directive from the chief of police in Lithuania on October 15, 1941. Under this directive, all officers, petty officers and enlisted men who had served in the police battalion for four weeks were to give the following oath:

“As a member of the self-defense units, I swear to be loyal, brave and obedient. And also to perform all my duties, and especially in the war against Bolshevism, the murderer of nations, conscientiously. I am prepared to give my life for this oath. So help me God.” (from http://www.genocid.lt/Leidyba/3/arunas2.htm )

Which of these oaths captain Žemaitis took or administered isn’t known. Under interrogation, he said he gave the oath to soldiers housed in barracks, i.e., he was under the command of lieutenant colonels Antanas Špokevičius and Karolis Dabulevičius. He himself returned to live with his family in Lentvaris after some time.

◊

Who are these colonels? Lieutenant colonel Antanas Špokevičius of the general staff of the Lithuanian military has been titled the commander of the Vilnius garrison. On June 28, 1941, he ordered the formation of a general staff headquarters for the Vilnius garrison. N.Gaškaitė-Žemaitienė has bestowed the title of burgermeister of Vilnius upon lieutenant colonel Karolis Dabulevičius.

Here is what historian A. Bubnys wrote about these military units in his article “Lietuvių policijos 2-asis (Vilniaus) ir 252-asis batalionai (1941, C1944)” [“The 2nd (Vilnius) and 252nd Lithuanian Police Battalions”]. The citation is long, but telling:

“On July 7, 1941, A. Špokevičius gave the last order (No. 8) to the Vilnius staff of Lithuanian military units. Starting July 9, Lithuanian military units in Vilnius were to be called ‘Lithuanian Self-Defense Units.’ On July 14, German field commander lieutenant colonel Adolf Zehnpfennig ordered Špokevičius to creat a ‘Vilnius Restoration Service’ (VRS) and stated ‘the Lithuanian military no longer exists.’ The VRS was to be divided into security, public order and labor services. Lieutenant colonel Špokevičius was appointed commander of the VRS and lieutenant colonel Karolis Dabulevičius of the chiefs of staff was appointed chief of staff [of the VRS].

The VRS services were the father to the three police battalions being created in Vilnius. Some Lithuanian troops were released from service and sent home. Under Zehnpfennig’s directives, the VRS security service was responsible for guarding the city of and area around Vilnius against ‘bandits and remnants of the Red Army,’ the public order police were to be used as ‘auxiliary police in internal service in the city of Vilnius’ and the labor service were to be used for ‘building and repairing important roads and bridges, and for urgent tasks and cleaning in the city of and area around Vilnius.’ Špokevičius’s order no. 1 of July 31, 1941, named who served on the VRS general staff and in the separate services. Among others named, there are lieutenant colonel Petras Vertelis of the [Lithuanian Vilnius unit] general staff, appointed advisor to the public order service; captain Aleksandras Kazakevičius, commander of the 4th platoon [?] of the public order service and lieutenant Ignas Račkus, commander of the 5th platoon [of the public order service?]. These people are closely connected with the history of the future Vilnius 2nd Police Battalion.

“On August 1, 1941, VRS was renamed “Self-Defense Service,” and the security, public order and labor services were renamed battalion 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Public order service advisor lieutenant colonel P. Vertelis was appointed commander of the 2nd Battalion and maintained this post until the beginning of October, 1941. Later he was appointed commander of the 14th Police Battalion in Šiauliai and commander of the self-defense units in the Šiauliai military district.

Captain A. Kazakevičius became the new commander of the 2nd Battalion. The 2nd Battalion was fully formed in mid-October, 1941. Even then it was clear the Germans planned to send the battalion to Lublin, Poland. There were 18 officers and 450 soldiers in the 2nd Battalion in mid-October. The battalion was composed of the chiefs-of-staff (battalion commander captain Kazakevičius, adjunct lieutenant Antanas Bražiūnas) and three platoons. Platoon commanders were lieutenant I. Račkus (first platoon), lieutenant Pranas Sakalas (second platoon) and captain Antanas Mėšlius (third platoon). Platoons were subdivided into units, and the units into chapters. Before leaving for Lublin, the 2nd Battalion mainly guarded military stores and patrolled the city and environs of Vilnius. Battalion soldiers also received further military training. They wore independent Lithuanian uniforms with a white armband on the left arm, and were armed with pistols and Russian rifles. The 2nd and the other two battalions were housed at the military facilities on Jėzuitų street.

“There is information the 2nd Battalion moved Jews from their apartments into the ghetto and took arrested Jews to Lukiškės Prison (late August and early September, 1941). According to the testimonies of some of the convicted soldiers from the battalion, the second platoon of the battalion, under the command of lieutenant P. Sakalas, took 500 Jews from Lukiškės Prison to Paneriai at the end of August or beginning of September. These Jews were reportedly shot by German security police and SD troops

“It is known from a German security police report and other sources that there was a mass murder carried out at Paneriai on September 2, 1941. On that day, Jews were marched in columns from Lukiškės Prison to Paneriai and shot. About 80 police did the shooting and another 100 formed the guard. Posters were hung up around the city with an announcement by gebietskommissar Hans Hingst proclaiming Jews were being punished for supposedly shooting at German soldiers on August 31. The mass murder operation went on for an entire day. According to the report by SD commander in Lithuania Karl Jäger, 3,700 Jews were shot in Vilnius on September 2, 1941, including 864 men, 2,019 women and 817 children.

“Some convicted battalion troops testified that around the end of September, 1941, 2nd Battalion soldiers escorted a column of about two thousand Jews to Paneriai and guarded the site during the mass shooting. Reportedly the Ypatingasis burys, or Special Unit, [made up of Lithuanians] under the German security police shot Jews that day. The Jäger Report entry for October 4, 1941, indicates 1,983 Jews, including 432 men, 1,115 women and 436 children, were shot in Vilnius that day. According to the information available, the 2nd Battalion didn’t commit mass murder during other operations to exterminate Jews.”

This is how Žemaitis himself recalled ending his participation within these groups:

“At the end of July in 1941 we were called into headquarters where Špokevičius ir Dabulevičius worked. The headquarters were set up in a building near the cathedral. Here we were told a Lithuanian unit was not to be formed.” (Interrogation of J. Žemaitis on July 2, 1953, conserved in the Lithuanian Special Archive, folio K-1, case 33960/3, tome 1, pp. 98-103 [?].)

◊

The people who suffered from these soldiers paint a somewhat different picture. Incidentally, Jonas Žemaitis figures in their testimonies as well. Let’s take a look at the work “The Battalions of Death and Destruction” by Joseph A. Melamed:

“Additional battalions were formed later on. Among the senior Lithuanian officers in command of the Vilnius battalions were Colonels Antanas Spokevicius and Karolis Dabulevicius. Among the battalion officers reputed for their cruelty were Majors Jonas Zemaitis-Vytautas, Misiunas, Kulikauskas, Daneitis, Pachiebautas, Jurksas, and Levizkas.

“Once the formation of the battalions was complete Spokevicius and Dabulevicius published the following directive to their troops:

“‘To all the valiant soldiers of the auxiliary battalions.

“‘Under the leadership of the great Adolf Hitler, the mighty German army has destroyed the forces of the Jewish Bolshevik bandits and liberated Lithuania from bondage and Jewish terror. We have now been given the historic privilege to fight alongside our German comrades, the finest soldiers in the world, and make our sacrifice in the cause of our civilization and culture.’”

and further on:

“Several other points should be stressed with regard to the Second Vilnius Battalion. After murdering thousands of Jews in Vilnius and the surrounding areas it was dispatched to Poland to continue its work there. The unit was commanded by Major Jonas Zemaitis, who having proved his efficiency and diligence in murdering Jews, was rewarded by the SS and promoted to the rank of Colonel.

“Although Lithuanian, Zemaitis was born in the town of Lomza in Poland and spoke Polish and thus proved a very able assistant to the SS in the genocide of Polish Jewry. At a later stage, the Battalion was transferred to Warsaw where, together with the Seventh Battalion, it assisted the German troops in destroying the Warsaw Ghetto following the uprising of 1943. After this task had been completed, it moved again to Lublin and continued to murder Jews at concentration camps in Poland.”

There are some unclear details in the above citations: the author calls Žemaitis a major who was promoted to colonel by the Germans. Lomża is presented as the city of his birth, whereas he was only raised there. On his part in the mass murder of Jews, the official position of the director general of the so-called Center for the Study of the Genocide and Resistance of the Residents of Lithuania, Teresė Birutė Burauskaitė, was voiced publicly in June of 2012:

“Partisan commanders did not take part in the Holocaust.”

Over the last year, the center has neither made explicit which commanders did not take part, nor published the more than one thousand names of people who, according to research conducted by the center’s own staff, did contribute to these crimes. Although this is hardly surprising, since, after all, the study resulted from a request by politicians in parliament who asked for a denial to counter so-called slander against certain partisan leaders who were said to have contributed to the mass murder of the Jews.

Many different questions arise from reading all this. I believe the time will come when historians fear no longer persecution by politicians and prosecutors, and then we will have answers to those questions.

Let them remain for now unwritten, as a mute testimony and accusation against those who should be doing the research, but do not research the bloody massacres committed in Vilnius more than 70 years ago. There is no statute of limitations for these crimes. There are other archives outside this country, where the archives suffered horribly after the restoration of independence, when some people who came to power had a vested interest. Those archives are gradually becoming accessible, and the historians who are studying their materials do not have any sort of clear instruction to “counter the slander.”

◊

But let’s go back to the version of events according to N. Gaškaitė-Žemaitėienė for a moment. She says Žemaitis went to Kaunas in August [1941] and stayed on Perkūnas Alley. He allegedly got work as a peat-mining technician on the board of administration of Kaunas Energy. I tend to think this is an interesting job: POWs and Jewish prisoners were massively exploited at this time in peat mining. But what Žemaitis actually did, what his job was in the administration, hasn’t been made public. And these interesting pages in the biography of the future president are left blank. Only prosaic matters are known. Work within this administration didn’t provide an adequate salary. Food was expensive in the city. The family grew in December, 1941, with the birth of his son Laimutis. In June, 1942, the family went to live at his parents’ native Kiaulininkai village in the Raseiniai district. Somehow the historians manage to omit that this was when the Nazis began to experience a lack of cannon fodder and mobilizations of men began. Žemaitis was surely a brave soldier and would not have deserted, rather he would have “gone to defend the homeland.” But this is what actually happened, he went to the countryside.

There, in the area around Šiluva, Žemaitis got involved with resistance activity. Together with general S. Zaskevičius he founded “units of freedom shooters.” Event followed up event quickly and soon the Nazi general Plechavičius and others developed a need for “anti-Nazi resistors.” On February 16, Lithuanian Independence Day, 1944, lieutenant general Povilas Plechavičius addressed the Lithuanian people over the radio. Men inducted into the underground were routed to formations called “vietinės rinktinės,” essentially “local select units.” The future president generalissimo became commander of the 310th local select unit and made the “freedom shooters” of Raseiniai district one of that battalion’s units. The soldiers were gathering, so one would expect a battle to erupt. But no battle did. The army called up by Plechavičius were not itching for a fight at the front. The Germans had a difficult time understanding the devotion of the Lithuanian officers corps (remember the priorities I listed earlier: a good salary, rubbing out domestic enemies, patriotic manifestations and a lack of desire to take on external enemies in battle). The Nazis decided to disarm them. Povilas Plechavičius was sent to Salaspils concentration camp to learn military discipline. Maybe the idea was that the Latvian SS troops at the camp would inspire bravery in the general, or perhaps they just wanted to keep such a valuable asset close at a place they might need him later. Perhaps an address to the Lithuanian people would have to be made again on February 16, 1945.

At the front, things went from bad to worse for the Nazis, and by February 16, 1945, the Soviets were back in Lithuania, so a Nazi address to the nation was no longer needed…

It’s interesting how things turned out for Žemaitis in this part of the story. If we give credence to Gaškaitė-Žemaitienė’s version of events, he turned command of the battalion over to his aid captain Romas Gintautas on April 1 and went on vacation. Then he went to Kaunas to have a look around. The epic and grand oil-paint mural could be titled “The Brave General Undertakes Surveillance.” He learned on May 9 in Kaunas the command of the “select local units” had been arrested by the Nazis, so… he didn’t return to his battalion. Our hero again deserted, leaving those under his command in darkness. Or perhaps he did not desert. He just went back to the Šiluva area. He was not in hiding.

It is known that at the end of the war he was recruiting people for training at Abwehr schools in the arts of social disruption and terrorism. We know Povilas Lukšas and L. Žukauskas were invited to attend. With the front drawing close, these two declined to go. Usually when people recruit others for spy school, we call them recruitment agents, so perhaps Jonas Žemaitis did not actually desert his command in the select local unit formed by the Nazis, perhaps he was simply given different orders to do a different task. But this part of the story is interesting if only for that one interesting dilemma: did he desert again, or was he an Abwehr stay-behind spy/soldier on the “hidden front?”…

The second Soviet occupation [of Lithuania] found Žemaitis in Kiaulininkai village. Maybe he hoped no one would notice him. Such hopes were dashed when the NKVD several weeks later began asking neighbors about the captain who deserted from the Red Army. He hid on his parents’ farm for a while, then went to stay with a relative near Dotnuva. When the weather turned cold, he returned to his parents, built a hiding place and hoped to remain there.

Near the end of January, 1945, partisans who had operated heavily in the area “discovered” Žemaitis, and asked him to join and, allegedly, lead them. Žemaitis politely declined, claiming he was waiting for orders from his superiors. Was he awaiting orders, or simply hoping something would turn up? On February 9, the Soviets made an address to those in hiding and called upon them to legalize themselves.

The partisans didn’t surrender and after wintering over, on April 23, Žemaitis once again took an oath on his sacred honor and became a member of the Lithuanian Freedom Army.

There has been a tremendous amount of information disseminated about Žemaitis the partisan. It’s just that there seem to be no major operations, all he did was hide, escape ambushes and make lists of enemies of the Lithuanian people, being a proponent of the idea of “punish them later.” Later when? One can guess from the instructions drawn up by the general on what to do when Lithuania would again be liberated from the Soviet enemies… How that punishment was meted out in 1941, Žemaitis’s underlings already knew. Many had experience in the mass murders of summer, 1941. But their liberators kept failing to show up. Paper armies and headquarters were drawn up and then passed into oblivion without any real operation at all. Communications between partisan groups broke off due to betrayals. In order to hold out and survive as long as possible, they tried to refrain from active hostilities. They avoided active fighting and limited themselves to agitating against Soviet elections, and confiscating Soviet documents. What happened to those villagers from whom they took documents seems not to have overly concerned the general and his subordinates. There is another interesting “routine” activity in which the partisan leader engaged: he regularly promoted and decorated outstanding partisans. They carefully recorded all this information. They didn’t stop writing everything down even after Soviet troops captured these sorts of documents several times. Finally the noose of betrayal brought the NKVD to their bunker hideout, apparently in the person of a partisan who had been in hiding together with them for less than six months.

Having been arrested by the NKVD, he could feel important again. At least according to Gaškaitė-Žemaitienė. Without being asked, he delivered a history of the partisans. Be was interrogated by Beria himself. Why this one prisoner was so important is hard to say. By 1953 there were almost no partisans left. The official story, that Beria wanted to end the post-war armed conflict through “negotiations,” is, to put it gently, strange. There is no information that they hoped to make a valuable asset out of Žemaitis. Furthermore, there is reason to doubt that such an asset was even necessary for their aims at that point. The Soviets had been doing this already for some time and there was no one left in the Lithuanian forests to trick. Nor was there any sense in compromising the already-defeated partisan movement. Jonas Žemaitis was sentenced to death and was shot at the Butyrka Prison in Moscow on November 26, 1954.

◊

After that followed a period of darkness and forgetting for several decades, when even his own son didn’t know about the president generalissimo’s activities. Happily, a bit later, Lithuanian patriotism had need of this legendary individual, and he was resurrected, at least as the name of the Lithuanian military college, and was rehabilitated as president and father of the nation by Lithuania’s Conservative Party, who indulge a habit of lightly spraying themselves from an atomizer filled with “eau de President” from time to time. The Conservatives’ toilet water isn’t a purely cosmetic application, however, for they wantonly and willingly ignore the admixture of the blood of two hundred thousand dead Jewish men, women and children.

◊