Protesters against ultranationalist groups must face police and prosecutors

O P I N I O N

by Lina Žigelytė

Lina Žigelytė

A spectre is haunting Lithuania — the spectre of feminism. All the powers of far-right Lithuania (this includes also far-rightists who know how to present themselves as center-right) have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre: puritans and watchful police officers, bloggers and self-described patriots.

The word “feminist” has become the most recent label to define the enemy of the state. This is because grassroots strategies — theatrical protests, DIY media, art projects, and solidarity with social minorities — are rapidly changing the landscape of local feminism. What is important, these strategies also invigorate the broader fight against neo-Nazism.

Over the years, a number of Lithuanian leftist thinkers, such as the philosopher Nida Vasiliauskaitė or MP Marija Aušrinė Pavilionienė used feminist perspectives to criticize far-right politics, Lithuanian Comstocks, and annual neo-Nazi processions. On numerous occasions they made clear to the public that sexuality and gender representation were part and parcel of nation building. Historically this was particularly evident with the rise of Hitler’s regime. The New Woman, because of her financial independence, sexual habits, and cultural tastes, was castigated as unwomanly and demonized as a reincarnation of the materialist Jewess. Misogyny, antisemitism, and homophobia go hand in hand.

In Lithuania, feminism as a movement that demands advancement of social equality for women has tackled the sexualized character of nationalism. Yet, especially during the past few years, the growing influence of far-right groups and their powerful connections with certain state-sponsored agencies, and increasing conflation of a generalized attempt by high society, including the president, Dalia Grybauskaitė, to identify all this with a putatively harmless patriotic stance gave rise to a number of initiatives that have now taken feminism an important step further:

Back to the streets.

This is an important shift, because public protest culture here in Lithuania is negligible and stifled by strict public assembly laws. However, some recent antifascist actions that brought together anarchists, queers, dykes, and artists were deemed as possibly too radical not only by people who openly express neo-Nazi views, but also by local authorities.

This response is the outcome of a tragic situation. Whereas annual neo-Nazi processions in Vilnius have grown from a few hundred in 2008 to 3,000 this past March 11th (celebrating the restoration of Lithuania’s independence in 1990), public antifascist protests in Lithuania are almost non-existent. Five years ago no one openly protested in the streets against the procession. This year only some thirty protesters were dispersed along the entire route of the procession. At the earlier February 16th event in Kaunas (celebrating establishment of Lithuania’s independence in 1918), less than ten protesters faced the crowd of over a thousand so-called patriots.

Over the course of the past year I participated in a few public actions that decried the rise of neo-Nazism in this country.

The only explanation I can give in response to such lopsided figures is this: it is scary to stand in public against neo-Nazism; moreover, local authorities discourage such attempts by regarding any protester as a potential criminal.

By law in Lithuania no more than fifteen individuals are allowed to participate in a public demonstration without a permit (until November 2012 the figure stood at nine). This also means that if the demonstration is larger, someone must take up the responsibility, which inevitably puts pressure on the organizers. Yet even when these protests do not exceed these limits, the police mostly regard their participants with acute suspicion and threaten to disband meetings unless identities and contact phone numbers are provided. Additionally, since some activists do not know their civil rights, they are not aware when police officers abuse their authority [see Geoff Vasil’s report on the February 2013 Kaunas independence day neo-Nazi demonstration].

None of the above encourages active citizenship.

Which is why after a small antifascist protest in Vilnius this past January a group of women put together a video about the aftermath of the protest. We wanted to demonstrate that the reactions to the protest were grounded in the sexualized character of nationalism. The protest consisted of ten individuals and more than half of them were women, queers, dykes, and anarchofeminists (uniformly nonviolent, unarmed, non-threatening, and non-interventionist in anyone else’s life). Subsequently, after the protest these activists were mocked with sexist and homophobic jokes in a rather extensive online hate speech campaign, and some women were harassed by the neo-Nazis.

Activism of any sort is a rather lonesome endeavor here in Lithuania. Especially if one is not part of some NGO. And some human rights NGOs lack the courage to stand up for much of anything. To make matters worse, quite a few local pro human rights folks do not favor small public protests, claiming that they make no or little difference.

Yet in March 2012 in Vilnius, when four women blocked the neo-Nazi procession of more than 1000 participants for a few minutes, the world noticed [see Defending History‘s report of the event]. However, even some human rights activists harshly criticized them. Their little protest action was allegedly too short, contained too few participants, and its content was ill matched for the occasion. But what these four women did was fundamentally different from previous antifascist activism in Lithuania. It was captured on film, and in many photographs.

Four women blocked the neo-Nazis’ progress up Gedimino for several moments on March 11th 2012. Photo: Defending History

Media rush to record melee as police forcibly removed the four women protesters at the March 11th 2012 neo-Nazi march on Gedimino Boulevard. Photo: Defending History

Instead of merely saying No to the neo-Nazi procession, these women became the mirror image of this crowd and showed how distorted and fear-driven it was. These women appeared in public dressed as pregnant Roma, pressed two fingers with black nail polish above their lips to invoke Hitler’s mustache, and cried out to the neo-Nazi crowd “Freedom to Lithuania!” Their standoff lasted less than three minutes, but effectively appropriated the most abject image of strangeness to a xenophobic hate-driven Lithuanian patriotism ― a pregnant Roma woman who breeds ever more “strangers” and is supposed to have black magic powers.

After the protest, which they called “Get knocked up for Lithuania and stand against Nazism,” the women ran as fast as they could in fear of possible persecution. By the way, one of them has been volunteering with the Roma of Vilnius Parubanka settlement for a couple of years and still does. Later in 2012, some of the participants of this street performance continued to participate in other protests that confronted nationalist beliefs. One of them initiated a protest in front of the Russian Embassy against the trial of Pussy Riot members.

Protest in support of Pussy Riot. Photo credit: Benediktas Januševičius

Women’s active participation in public protests against far-right ideology in Lithuania is a direct response to the fact that this ideology has always targeted women and still does. Debates about the so-called family values haunted the parliament throughout the Conservative rule of 2008-2012. Currently, religious and conservative organizations are lobbying against the European Council’s Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, because the convention states that gender is socially constructed. Domestic violence in Lithuania is double the EU average, a statistic ignored by the government’s spin-meisters, and not something to be proud of, or to be proud about hiding, on the event of the country’s assumption of the rotating European Union presidency in July.

Nationalism imposes ideas of supposedly morally proper behavior upon women and treats them as secondary to men, because nationalism is an ideology of rigid hierarchy and power. That is not to say that all women always oppose nationalism. A number of women historically demonstrated that in spite of nationalism’s masculinist rhetoric, women always actively participated too in the establishment of far-right political regimes. For many such women participation in far-right groups offered an opportunity to secure an active social role and a sense of importance. Perhaps that explains why in Lithuania each year the front line of neo-Nazi processions contains more and more women. These women help to give the impression that these marches are peaceful and therefore the mainstream media mostly fails to cover incidents when participants of these marches verbally assault or threaten those who protest against neo-Nazis

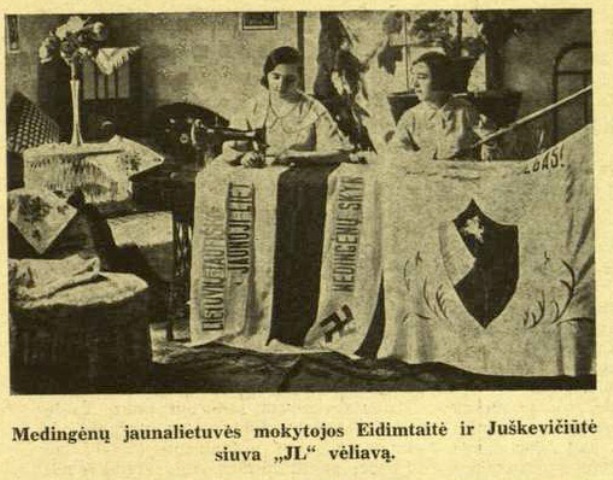

Historically in Lithuania some women also actively supported far-right groups. Interwar images of a Lithuanian youth organization “Young Lithuania” which imitated the Hitler-Jugend to mobilize local youth, show women sewing the organization’s flags with swastikas and other fascist symbols.

From the magazine “Jaunoji karta” (no. 20, 1935). Members of the Medingėnai section of Young Lithuania, Eidimtaitė and Juškevičiūtė, are sewing the flag of Young Lithuania…

Another symbol of the same organization is currently used by the Union of Lithuanian Nationalist Youth, the same organization that has from 2009 to this year organized neo-Nazi processions in Vilnius and supported an openly homophobic and xenophobic party during last autumn’s local and parliamentary elections. Their symbol, called “three flames” visually evokes a swastika type image, which in any case it has empirically become by virtue of being the symbol of choice of those who flaunt swastikas when it is convenient for them to do so.

When in January 2013 I attended an antifascist protest in Vilnius with a poster where this symbol (some call it “the flaming swastika”) was crossed out along with a Nazi swastika and the words “No more 1933 in Europe” I was asked to go to the police station, because the fascist group, the Union of Lithuanian Nationalist Youth, wanted to press charges against me for instigating hatred and physical violence against members of this organization. The office of the prosecutor general actively considered but eventually decided not to pursue these charges.

Antifascist protest in Vilnius, January 2013. Sign at left says No Pasaran to three symbols: a medieval national symbol in recent years hijacked by the neo-Nazis (causing police and prosecutors to turn their attention to the protesters rather than the neo-Nazis who pursue them); the swastika; the symbol of the Greek neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn. The full text of the sign at the right (only partially visible on the photo) reads: “Better shit on the head than Nazis in the government.” Photo: Benediktas Januševičius

Far-right regimes always target women who fail to fit the image of a patriotic woman: whether they look unfeminine, use contraception, or appear to be too emancipated. In response, far-right regimes have always met with daring opposition from diverse groups of women.

And they always will.

This opposition might not immediately gather a multitude, because the mustering of multitudes requires resources both financial and organizational. Small-scale, bottom-up, and DIY action is the fuel of a society where individuals are conscious and daring. Such action sustains social movements and produces a sense of belonging to an ethical community.

Lina Žigelytė is an LGBTQ activist, interdisciplinary artist, and art critic. She is a graduate student in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester (NY).