M E M O I R S / O P I N I O N

by Monica Lowenberg

In 2011, I made my first journey to Riga, the capital city of Latvia.

A few months before, I had been tracked down by two distant cousins on a genealogy site, quite out of the blue. I remember the strange feeling I had when one of them asked me if I felt “Latvian.” Latvian? German Christian, German Jewish, British, yes — but Latvian Jewish? No.

It was a question I had never asked myself for the Latvian side of me had for forty-seven years lain buried behind an invisible, dark curtain where no roads led and only ghosts travelled. With the disappearance of my paternal grandfather David Loewenberg or Levenbergs, who had been born in Libau/Liepaja, Latvia in 1875 and the disappearance of my uncle Paul Loewenberg/Levenbergs, born in Halle an der Saale on 20 January 1922 and last heard of in Riga, Latvia was a country that was simply not spoken about in my parental home.

A visit to the state archives in Riga in October 2011 led to a roadmap that clearly signposted the entrances and exits my Levenbergs family were forced to take. It is a map I hold today with a story that I and other second generation children feel compelled to narrate until, I suppose, it is heard, formal apologies given and perpetrators and collaborators no longer honored.

The first personal story here was “Latvia — A Personal March through History” first published in 2012 by the Association of Jewish Refugees and Second Generation Voices. The second is a short film, A Tale of Three Monkeys (video) a very recent piece of work, published on Vimeo on 25 October 2013, part of a challenge posed by Sony and Kino London where ten strangers including myself were put into three groups, generously given equipment by Sony and asked to do a six minute film in two weeks on the topic… “Monkeys make best friends.”

As Sony is a Japanese company, I decided to play on the Japanese proverb, “See no evil, Hear no evil, Speak no evil.” Focusing on three talking heads, the third based on my grandmother Marianne Loewenberg nee Peiser, I wanted to explore the idea of what is actually evil. Is evil simply supernatural? Is evil what people do to each other? Is evil what governments have done and do to their citizens? Is evil simply turning a blind eye? You decide.

I make absolutely no claims of being a film maker.; But just making A Tale of Three Monkeys made me realize how incredibly skilled a profession it is. I did the film because the opportunity arose and it seemed interesting.

My persevering, committed team and I had some horrible technical hitches where at the first screening, due to problems with the sound, we had no music or sound effects which in many respects perfectly matched the dilemma my grandmother and then I experienced regarding speaking about the past and playing the violin, in particular pieces by Beethoven (a composer appropriated by the Nazis). However, at the end of the day and as a team, we felt strongly that music and sound effects had to be put into the film, not to diminish the trauma, give “a happy end” by breaking the spell of silence but by showing that music, in particular the Beethoven piece used in the film and one my grandmother used to play with Henri Hinrichsen (the famous music publisher of CF Peters and the man who saved her life), is not just an evocative, pleasant piece of music but one that holds and can conjure simultaneously, due to the knowledge of history we have, memories of “beauty” and “evil” at one and the same time.

◊

Latvia – A personal march through history. . .

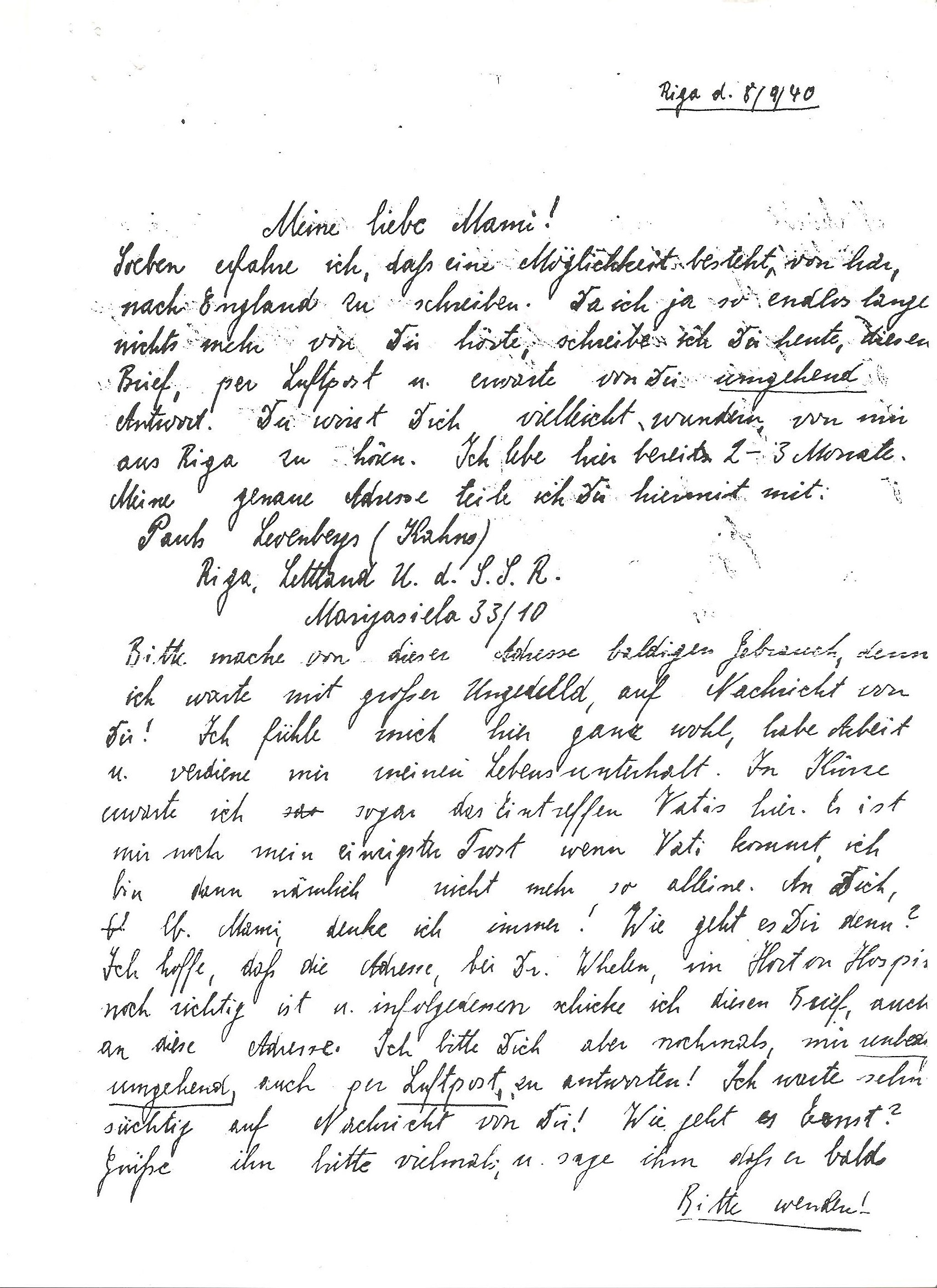

Riga, 8 September 1940

Dear Mami!

I have just found out that there is an opportunity to write letters from here to England. As I haven’t heard from you for such a long time, I’m writing this letter to you by airmail and I’m waiting for an answer by return of post.

You might wonder why you are hearing from me from Riga. I’m living here for the past 2-3 months now. My exact address is:

Paul Loewenberg (Kahns)

Riga, Latvia USSR

Marijas iela 33/10

The last letter Marianne Loewenberg ever received from her son Paul

“Marijas iela no 33, Apartment 10. Do you know where it is, Aleksandrs? Is it this street?” I ask and I point to Marijas iela on the free town map I was given in my hotel. “No, the streets are different to what they were before,” Aleksandrs replies, “Come, it is not far now” and dutifully I follow him as the Baltic wind kicks leaves around our feet.

I can still see the fish market and the golden sprats flapping their fins and crying for the sea; the oldest wooden house in town, standing defiantly in the midst of a busy street and dwarfed by Stalinesque administrative buildings; the regal white opera house and the less regal production of Don Giovanni with singers flirting in bikinis; the State archive with its classroom seating which introduced me to my Latvian family over the last few days; the amber sellers; the flower sellers; the burlesque night clubs; the pastel-colored buildings; the cobbled streets; the town hall with its impressive spire with a view of the Daugava (Dvina) river and the house of the Black Heads — a group of unmarried merchants.

And then I think back to my discoveries in the Latvian State Archives on Slokas Street the day before, the names of my Latvian family. They are names in black ink on time stained pages, in Russian, in black leather bound books. I have ten piled up in front of me and a piece of paper that the archivist has kindly given to me with the Russian spelling of the name Levenbergs. I search the names and scrutinize every sweep of a pen.

Over three days I find them, they come alive and wave to me from the pages, they open a window into a patriarchal world that nurtured traditional roles, dates telling me when they were born, married but not where they died…

“Your grandfather’s father was called Lazzers Levenbergs, he was an omem,” the archivist says, “a soldier”. A soldier? Yes, a soldier who fought for his country and probably proudly and then he married Minna, Minna Bernstein and they had eight children and they lived by the sea in Libau and they ran a furniture shop.

They worked hard and they traded as commercial merchants and they hoped that their business would do well so that their children could be educated. They helped my grandfather David go to Dresden University to study engineering and their eldest twin boys Moyshe and Abraham, born shortly after they married in 1867, left Latvia as well. Moyshe went to Paris and Abraham to Tehran, and their daughter Tante Gertrud married a German solicitor called Schindler and lived in Switzerland. But their other children, Joseph and his three other sisters Zlato, Rivka and Judith and his aunts, Lazzers’ sisters, Miriam and Deborah, stayed in Libau and they lived in Libau and they had children in Libau and they lived by the sea and they played in the dunes and they kicked the sand.

Did Roland, the legendary knight who proudly surveys all who pass him in St. Peter’s Church, protect them, being the patron of merchants and the protector of peace and merchants’ rights?

I am tired, my feet hurt but we can’t stop, it’s way past lunch time and most of the restaurants and cafes are no longer serving látkes with sour cream. A hot coffee would be welcome to fight off the cold and I am grateful that I have got two pairs of thick socks on but we can’t stop. Before I fly back to London tonight I have got to see the place where my uncle had lived, before he was sent to the Riga Ghetto.

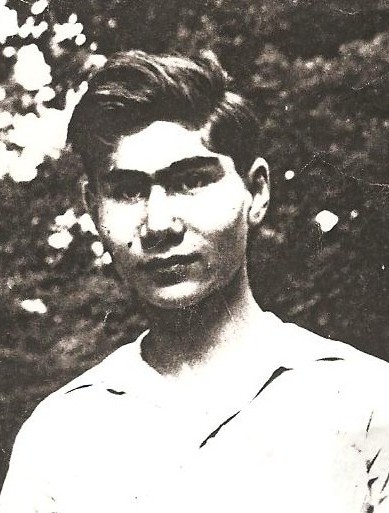

Paul Loewenberg (Levenbergs)

I am hoping as I walk down the cobble streets of old Riga that I will have a moment of revelation, that the stones will suddenly speak to me and help me to understand why; why a 19 year old young man who was born in Halle an der Saale, Germany on 20 January 1922, one year before my father, a young man whose father, David, a self-made man, a hardworking man, an engineer who was born in Libau in Latvia 29 November 1875, whose factory in Berlin was taken away from him in 1935 and had to place his sons into an orphanage, who in early 1941 left his last address in Berlin Altonaer Strasse 16 to head a tool factory in Moscow and disappeared; whose mother Marianne an opera singer and violinist born in Leipzig in 1893 and with the help of the Hinrichsens of CF Peters, despite managing to escape to England in April 1939, never sang again? Why was he taken from his lodgings in Marijas iela to a ghetto? Who would do such a thing to a young man, still really a boy, away from home, homesick, lonely and scared? Who would do this? When they came to collect him on the 4th of October 1941 from Apartment 10, Marijas iela 33, when they knocked on the door what did Frau Kahns say? Did her heart stop still as they knocked on the door, when Paul was told to leave the building with them? Did he put his beret on to one side as my father remembers him always doing? Did he wear thick socks, did he take anything with him or did he have to leave everything he owned behind, behind in his small bedroom in Apartment 10, no 33 Marijas iela? Did he put on a brave face but secretly yearn to have his mother’s arms wrap him warm? Who would do this to a boy? Did the men who collected him speak in German or in Latvian? Even though my grandfather was Latvian Paul and my father had been born in Germany.

Paul would not have understood them if they had spoken to him in Latvian. When they saw him, did they not see that he could have been just like one of their sons, one of their nephews, one of their cousins? Did he look so strange, so alien, so dangerous that they needed to collect him and take him to a ghetto? Did he perhaps tilt his eye in such a way that said subhuman or dangerous communist sympathizer?

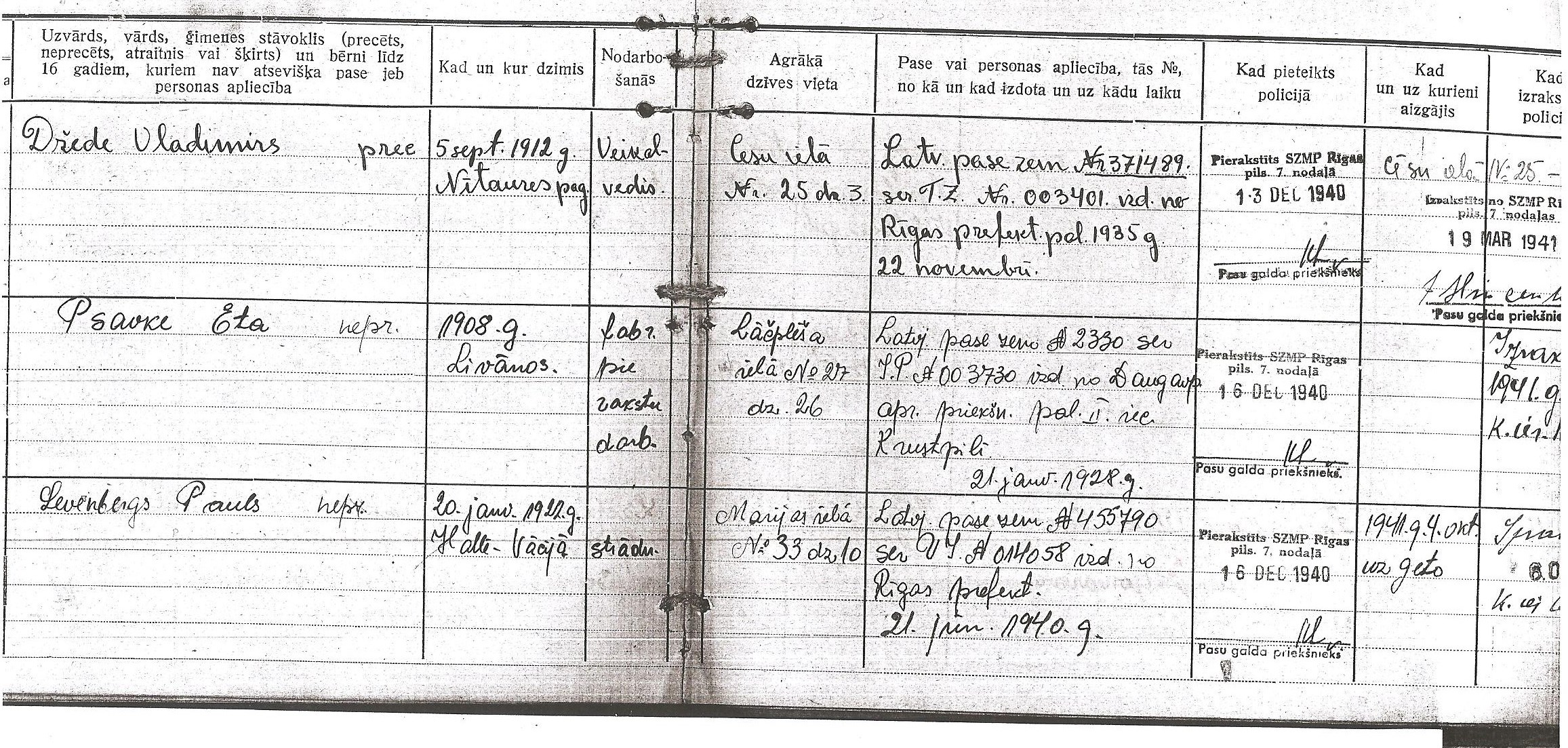

Document confirming that Paul Loewenberg (Pauls Levenbergs) was sent to the Riga Ghetto

“This is Lacplesa Streeet,” Aleksandrs calls out. Paul lived here as well. “Yes, it was part of the ghetto.”. It’s a long street; we walk along it with traffic rushing past. Maskavas St., Vitebskas St., Ebreju St., Lauvas St., Liela Kalna St., Lazdonas St., Kijevas St., Jekabpils St., Lacplesa St., the original boundaries of the Riga Ghetto, officially announced on August 23, 1941. October 25th 1941: its gates were locked and 29,602 Jews were driven together under strict custody behind barbed wire in the area where about 13,000 people had lived before. Among them 5,652 children, 8,300 invalids, 9,507 women, 6,143 men and my uncle. “What day is it today?” I ask Aleksandrs, “Wednesday 26 October 2011.” When did the archivist solemnly hand me a small rectangular book with Paul’s name in it, the black book that neatly listed his address 33 Mariajas iela , his date of birth and the word “Geto” underneath the date 4 October 1941? Yesterday, 25 October 2011. Time stands still and I freeze.

“How many people were killed?” I asked Aleksandrs,” Paul was a workman, he was 19, he was young, he could survive, did he survive? Do you think he survived?” “Perhaps, I don’t know,” he replied.

On 29 November and 8 December 1941 the large ghetto was annihilated in murderous actions. Approximately 25,000 inhabitants of the ghetto were brought to Rumbula to the woods, a few kilometers outside Riga, where over a thousand Latvian Ārajs commandos robbed them, accompanied them, guarded them before SS soldiers shot them and packed them into pits in the ground like sardines.

This is the first Jewish secular school, 141 Lacplesa Street. It was run by Rabbi Dr. Max Lilienthal. A German translation of the Torah made by the famous Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn was one of the main teaching aids used at this school. Up until the Holocaust, Riga was a thriving hub for artists and musicians, composer Oscar Strok, violinist Sarah Rashin and even Wagner worked here. Only one in ten Latvian Jews survived, only one. This is a photo of the famous historian, Prof. Simon Dubnow, whose last words in the ghetto were, “Write, Jews, write.”

Aranka, David, Israel, Jossel, Mark, Modechai, Rebecka, Rivka, Fanny, Jenny, Lilia, Minna , Rafael, Rosa, Rachel, Wiliam, Abram, Selig, Scheine, Sore, Rosa, Paul. Albert, Benjamin, Eugenia, Haim, Judith, Lia, Minna, Paul. Their names and plaques in the ghetto museum flash past me, all Lewenbergs, all taken to the ghetto. I stare at them and they look back at me in black straight suits made of capital letters. Look at this photo: it is the burning of the synagogue, where 300 people, 300 Jews were burnt alive iside. Look at this man: “He looks as if he is laughing.” “Yes.” He is not a German soldier, he looks like an ordinary man, a man who buys furniture and sits and sleeps in it.

“Here, this is no 33 Marijas iela.” Aleksandrs points to a beautiful old art deco building in a street that used to be a thriving hub for tailors; the street is now called Aleksandra Caka Iela. I would never have found it. Inside, a sweeping banister dominates the landing and on the wall a list of businesses located in the building can be seen. Located in Apartment 10 a company called Manol now does its work. The walls around their office are neon yellow, we knock on the door, no one is in but somewhere behind that yellow door, Paul wrote the last words his mother ever received from him.

Please use this address soon, because I’m waiting for an answer from you with eagerness! I feel quite well here, I work and earn my living. I’m expecting Vati to arrive soon. It’s my only comfort that Vati is coming, because then I won’t be so lonely anymore. I’m always thinking about you, dear Mami! How are you? I hope that the address at Dr. Whelen at Horton Hospital is still the right one. In case it is not I’m sending the letter to this address as well.

I beg you again to answer as soon as possible, by airmail! I’m longing for an answer from you. How is Ernst? Best wishes to him and tell him, that he will hear from me soon. Dear Mami, I’m so happy that I can finally write to you. My heart is full of worries because of the long separation. If I can even hope to see you again, How happy I would be if I could be with you. In my thoughts I’m always with you dear Mami. When I hear back from you I’ll give you more details about me. Until then, this short greeting.

I greet and kiss you many times, your loving son, who always thinks of you!

Paul

“Who always thinks of you,” those words they rush through my mind and I can’t let them go and I think of a photo a friend of mine sent me of a plaque inside the oldest ghetto in the world, in Venice, created in 1516, the very place where the word ghetto originates from. The plaque reads, “Perché le nostre memorie sono la vostra unica tomba, [for our memories are your only graves].” Did we see a plaque in the former Riga Ghetto? I can’t recall.

I first visited Riga in October 2011, seventy years after the Riga ghetto had been formed and when Latvia officially commemorated 450 years of Jewish life in Latvia. In the same year, the Jewish community commented on an increase in antisemitic attacks. As has been tradition since 1998 in Riga, on March 16, 2011, in the heart of a NATO and EU country, more than 2,500 people paid tribute to Latvians who fought on the side of Nazi Germany in Waffen SS detachments during World War II. Close to 70,000 Jews, or over 90 per cent of Latvia’s pre-war Jewish population, were killed in 1941-42 by German SS and Latvian collaborators, many of whom later joined the 15th and 19th divisions of the German SS in 1943. The brutal murder of Latvian Jews using the “Sardinen Packung” method, was the second worst atrocity in the Holocaust, yet the Museum of Occupation in Riga only devotes a couple of stands to their deaths.

As a direct consequence of my visit to Riga and what I discovered is occurring there today I started the petition “Stop the 16 March marches in Riga and Latvians revising history!” as I sincerely believe glorification of pro-Nazi armed forces during World War II has no place in a European Union / NATO / OSCE capital, a city that in 2014 will be declared the European capital of culture in the country that from January 2015 will hold the rotating presidency of the European Union.

The petition, launched 20 January 2012, ninety years to the day from the date of birth of my uncle, Paul Theodor Loewenberg, a native of Halle an der Saale, who at age 19 was sent to the Riga Ghetto on the 4 October 1941, is as much an act of commemoration of the victims of Nazism as it is a tribute to the European parliamentarians, including a number from Latvia, who wisely and courageously signed on the 20 January 2012, the Seventy Years Declaration, commemorating Wannsee, a declaration which specifically rejects glorification of Latvia’s Waffen SS, along with Estonia’s Waffen SS and the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) in Lithuania.