OPINION | LATVIA | BELGIUM | COLLABORATORS GLORIFIED | HISTORY | POLITICS OF MEMORY

◊

by Roland Binet (De Panne, Belgium)

◊

Before my initial Defending History article last March on the monument to the Latvian Hitlerist Waffen SS on Belgian soil, there had only been one Belgian trying, from December 2020 onward, to get attention to what he deemed an infamy. Wilfred Burie, president and founder of the “Belgians Remember Them” association, alone compiled a list of names of more than 4,000 personnel of Britain’s Royal Air Force, whose planes were shot down in Belgium and, for each person, what became of them. There had been a parliamentary question to the Federal Belgian Minister of Justice to no avail, and, also, some articles published in minor French-speaking newspapers as well as outcries from Belgian Jewish organizations, also without consequences. On April 28, an article of mine was published in the French-speaking newspaper “La Libre Belgique” under the title “Why This Monument in Honor of the Waffen SS in Zedelgem?” with quotes from Lev Golinkin’s pioneering study on Nazi monuments around the world, published in New York’s Forward.

Then, on May 20 of this year, Michel Bouffioux from the weekly Paris Match Belgium, published his well-documented “Latvian Waffen SS celebrated in Flanders” including interviews with Dr. Efraim Zuroff (Simon Wiesenthal Center) and Dr. Leanid Kazyrytski (University of Gerona in Spain). He subsequently published sequels to his initial article with among other international reactions comments from Lev Golinkin.

Unfortunately, all reactions to that point had been only in the French-speaking part of Belgium. Then, on May 31, the website Apache.be, a Dutch-speaking media outlet, published a well-informed article with the flamboyant title “Great Damage for Zedelgem’s Image from the Latvian Waffen SS Monument,” with interviews of established Flemish historians. And finally, Jan Vanriet, a well-known Flemish painter, son of a Resistance fighter, who had previously been featured in a film about the resistance in Belgium, whom I had contacted on that matter, alerted Flemish-speaking media, and two articles were simultaneously published in Flanders on June 25, in Het Nieuwsblad (“A Sudden Realization: This is a Nazi Monument!”) and De Standaard (“Zedelgem Hhonors 12,000 Latvian Collaborators”).

But the town council of Zedelgem refuses to demolish or remove the monument, saying repeatedly that it is a monument to peace and assuring that a plaque will be added to it, explaining that “there shall be added an extended text in accordance with historical specialists, in order to avoid all susceptibilities” (Het Nieuwsblad, 25 June, 2021).

But, as the old saying goes: Whoever sleeps with dogs gets up with fleas. It seems to me that I should explain why I think that the link between the town council of Zedelgem and the Museum of the Occupation in Riga smacks of distortion of history, rewriting of history, plain revisionism and veiled far-right antisemitism.

During his inauguration speech on the unveiling of the Beehive Monument in Zedelgem on September 23, 2018, Mr. Nollendorfs, Chairman of the Board of the Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, in a surge of enthusiasm and romanticism quoted some lines from the famous poem John McCrae had written during World War I, in May of 1915:

- In Flanders fields the poppies blow

- between the crosses, row on row

- that mark our place and in the sky

- the larks still bravely singing fly

- scarce heard amid the guns below.

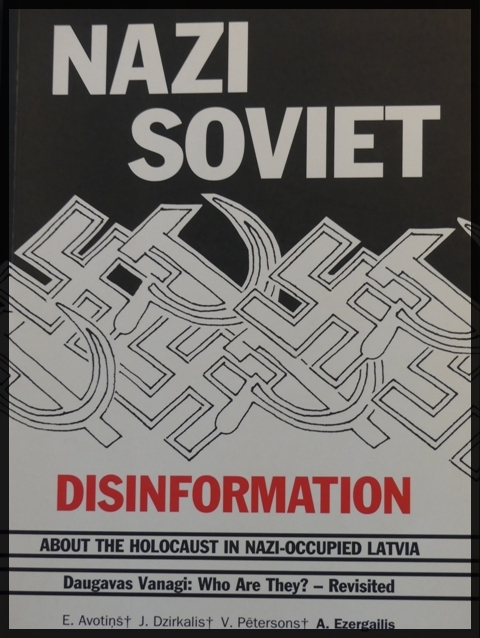

He had beforehand made clear that “Zedelgem and Flanders are no strangers to occupation and the violence, destruction and suffering of war.” Let us remember that McCrae was a Canadian army doctor who in April 1915 saw and treated allied wounded soldiers in Flanders’ Fields victims of the first gas attacks by the Germans, on the Canal embankment. He died in 1918 at the hand of German soldiers, the forefathers of the comrades in arms of the Latvian Waffen SS men honored by a monument in Zedelgem. Mr. Nollendorfs’s comparison displays a twisted, perverse and unseemly logic; but at the same time, it allows us to understand how intricate, tortuous and illogical propaganda and the rewriting of history operate in our own times: make victims out of the perpetrators of war crimes and genocide of the Jews, and let us forget that in fact there had been real victims who lost their lives. This well-oiled machinery is perfectly brought to bear in a propaganda tool where we find the name of Mr. Nollendorfs as Copy Editor. That is the book: Nazi-Soviet Disinformation about The Holocaust in Nazi-Occupied Latvia. This book was published in Riga in 2005 and financed by the “Latvijas 50 gadu okupācijas muzeja fonds” (Fund of the Latvian Museum of 50 Years’ Occupation).

Its author and supposed defender of Latvia’s cause and honor is the historian Andrew Ezergailis. He is the famed author of the well-know classical study of the Holocaust in Latvia , The Holocaust in Latvia 1941-1944”. As explained in my June 2013 opinion piece in Defending History, “Tone and Moral Judgment in a Famous Book on the Latvian Holocaust,” this historian never ceased to defend the Latvian Nazi collaborators, sometimes with aberrant and illogical, nonhistorical statements. Three such statements will illustrate his biased logic.

(1): “It is tempting to speculate that without alcohol there would not have been a Holocaust; assuredly there would not have been an Arājs commando. It was alcohol that broke down the inhibitions of the young men and enabled them to kill for the first time, and it was alcohol that brought them to the killing pits.”

(2): “The participants felt that there were levels and degrees of involvement in the killing.”

(3) “The Jews of the ghetto did not go gently to Rumbula.”

In the preamble of this new book Nazi-Soviet Disinformation (page XV), Ezergailis sets the tones and hues of what he will write: “Why is the folklore about the Holocaust believed more than histories of it?” Thus, it seems that Ezergailis wants to go a step further and to completely disregard everything about the Holocaust in his view tainted by the Jews. He has an entire chapter entitled “Holocaust Folklore” (p. 84 ff.). He is in top form on that subject and he writes in rampant ideological flights of his fertile imagination; let us take a few examples of his biased prose:

“Upon Hitler’s orders with the help of Holocaust folklore and revisionist historians, the Germans have almost gotten away with murder of the Baltic Jews (…) There is the viewpoint that I have characterized as folklore that originated already during the Nazi occupation and was started in large part by the Fuehrer’s pronouncements. And there is history that bases its conclusions on a smorgasbord of sources that include Nazi and Soviet documents and does not exclude the eyewitness accounts of survivors.”

“One must note that all of the pictures and film clips that today are used to illustrate the Holocaust, were taken by German public relations crews, to prove that it was the ‘natives’ and not the Germans who did the killing.”

Apart from the KGB and its agents as being one of the two sources of misinformation about Latvia’s role in the Holocaust, Ezergailis does not spare one of the most revered and known survivors and esteemed author on the Holocaust in Latvia, attacking him without pity and frontally:

“…but as far as the accusation of collective guilt against the Latvians goes there are two sources. The first one is Max Kaufmann’s Die Vernichtung der Juden Lettlands, published in 1947.”

In other chapters of this most recent book one can find a fund of historical and verifiable facts about the Holocaust and sometimes very-well thought out theories, alongside and intermixed with the far-right revisionists’ staple statements that cast doubts on what many unbiased West European and American historians wrote about the Holocaust in Latvia. Here are a few examples:

“The folklorists of the Holocaust have claimed that atrocities began during the so-called interregnum, the spell of time between the Red Army’s retreat and the arrival of German forces. But to date those statements have remained in the realm of assertions, lacking documentation.”

Let me quote here what author Myriam Zalmanovitch writes, accurately, in the chapter “The Holocaust of the Latvian Jews” in The Extermination of the Jews in Latvia 1941-1945, wrote on the subject of the interregnum:

“The armed units (…) were created at the end of June 1941. They were formed by farmers, workmen, students, members of the local intelligentsia, officers from the professional army. It is no wonder that they volunteered to work for the Nazis (…) Availing themselves of the vacuum of power, they entered in the houses of Jews, stealing their possessions, brought the men with them whom they almost immediately shot, insulted and beat the families. At the beginning of the German occupation, the situation got worse. Attacks against Jewish homes were organized, accompanied by pogroms, murders, the burning of synagogues and places of worship.” (translation from the French edition).

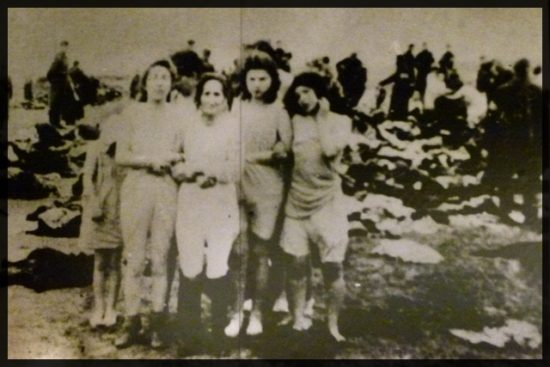

Ezergailis proceeds to deconstruct some icon pictures of the Holocaust in Latvia; let us look at some examples: the picture of the Epstein family moments before they were killed in the dunes of Šķĕde near Liepāja on December 15, 1941 (prominently displayed on one of the walls of the Museum of the Jews in Riga). He notices that “…its background illustrates the role of rifle-toting Latvians. The picture is conspicuous for the missing Germans…” Then, there is the picture of male detainees marching on Brivibas Boulevard, escorted by armed civilians, taken on July 2, 1941 (this picture was one of those exhibited in The Extermination of the Jews of Latvia 1941-1945). Ezergailis’s explanation? “The picture could not have been taken on 2 July 1941, because the people in the picture are dressed too warmly for a hot July day. One does not wear overcoats in July in Rīga.”

Another one of Ezergailis’s “historical” rebuttals concerns the burning of the Synagogues in Riga on July 4, 1941. This is what he writes: “It is true that synagogues in Rīga were burned on 4 July, and it is possible that some religious Jews were incinerated. The story of hundreds of Jews being burned, however, belongs to the folklore of the Holocaust.” Note the use of the words “religious Jews,” clearly an antisemitic slur. Let us look at the undeniable facts: On 15 October 1941, the leader of Einsatzgruppe A sent this report to Berlin

“…Even in Riga it proved possible by means of appropriate suggestions to the Latvian auxiliary police to get an anti-Jewish pogrom going, in the course of which all synagogues were destroyed and about 400 Jews killed.”

(report by Einsatzgruppe A in the Baltic Countries – October 15, 1941).

Another interesting impartial eye to the burning of the synagogues belongs to an ethnic Latvian who helped save more than 50 Jewish lives, Žanis Lipke, who remembered that

“On the evening of 4 July, Arājs and his cronies burnt down the Riga Great or Choral Synagogue on that same street. About 300 Lithuanian Jews, mostly women, children and old people had found refuge in its basement (…) As the synagogue went up in flames, they shot and threw grenades at mothers who were trying to throw their children out of the windows of the burning building. All these people died a horrible death. On the same day, two other synagogues were destroyed.”

(from: Lipke’s List – The story of Žanis Lipke and the Jews he Saved, published with the support from the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia, and the Riga City Council).

In order to understand the true scope of Latvian participation in the extermination of the Jews, either by individual killings or by slayings committed by organized units, you have to bear in mind that at the time of the Second World War and even until now, many Latvians who had seen their independent country occupied by the USSR in May 1940 equated the Jews with the Soviets. The well-known British historian Ian Kershaw has described what happened at the time the Germans invaded the Baltic States:

“When the Germans came through the Baltic States at the beginning of operation Barbarossa, it had absolutely no difficulty in finding willing collaborators among the nationalists in Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, who considered the Germans as liberators who delivered them from the yoke of the Soviet domination. Tens of thousands of citizens from these countries had been deported by the Soviets to the Gulag during annexation {approximately one week before the start of the war. The repression by the Soviets had reached entire communities. […] Many in the Baltic States were ready to believe that the Jews and bolshevism were not to be differentiated, and that the Jews were responsible for the suffering that the Soviets had caused (…) the Germans and their collaborators could stir up Jew-hatred among extreme nationalists without too much difficulty.”

Ezergailis also offers a new definition of “collaboration,” making a dialectical difference between the collaborators of Western Europe and the others in Eastern Europe:

“‘Collaboration’ is another word that has confounded the historians of Eastern Europe. One must remember that the concept originated in the context of the Nazi occupation of Western Europe and Scandinavia. In Eastern Europe, where the Nazis deemed entire populations racially inferior, Untermenschen, the concept does not have the same application as in the West. In Latvia, the Germans rejected all offers of ‘collaboration’, and all ‘collaborative’ projects were organized by the Germans.”

This is of course historical hogwash and pure propaganda. The men who joined the Arājs Kommando, the Schutzmannschaften, the Police Battalion units, the auxiliary police, the volunteers of the Latvian Legion, the Latvian civilians who killed Jews in small rural towns (mainly in July and August 1941, as described in the standard work ‘The Extermination of the Jews of Latvia 1941-1945) crept from under their social status of Untermenschen and suddenly all the hatred they felt towards the Jews of their country got a nearly God-given sanction: they were free to kill anyone they wished, steal, maim, beat, humiliate with or without the fiat of the Germans and without any risk of ever being brought to justice for the crimes committed.

Let us look at two facts.

First: during World War II in Latvia, the names of 662 rescuers of Jews are known: 813 were hidden, 594 survived, 219 were found and shot, a bit more than 50 were saved by Žanis Lipke alone (source: Lipke’s List). this is very little for a country of over two million inhabitants.

And second, what Ezergailis never mentioned is the veil of silence that took hold of Latvia and allowed that more than 100,000 Latvian and foreign Jews being murdered on its territory without any qualms of conscience from the largest part of the Latvian population. The Jewish survivor Bernhard Press has perfectly expressed this opinion in his classical work The Murder of the Jews in Latvia 1941-1945:

“It was not only a sea of hatred that surrounded us, it was also a sea of silence. Tens of thousands and hundreds of thousands were witnesses of the most horrible crime in human history and remained silent about it. The politicians also remained silent, the same ones who had granted us our civil rights twenty years before (…) Why didn’t they try to bring their own countrymen to their senses? This would have been the task of the country’s intellectual leadership. But, it was just this leadership that did nothing. Why not? Because most of the intelligentsia, together with the majority of the Latvian people, were entirely in favor of the ‘elimination’ and not only encouraged the mob to shed blood but also actively participated themselves.”

The book Nazi Soviet Disinformation about the Holocaust in Nazi-Occupied Latvia, of which Mr. Nollendorfs was Copy Editor and Riga’s Occupation Museum is publisher is in part a work of abject propaganda, pseudo-historical arguments, rewriting of history, and veiled antisemitism. It is as if from the early beginning of the slaughter of the Jews of and in Latvia, there had been a well-thought-out plot to put the blame on the poor innocent Latvians, the victims of this world-wide disinformation campaign. And some of the villains were Hitler of course, and later the KGB and its disinformation agents but also that Jew Max Kaufmann. What did he know about the Holocaust, just because he had been through the process, did that give him the right to accuse the Latvians of mass voluntary participation?

Now, we also have the town council of Zedelgem rewriting history, telling the world that the monument unveiled in 2018 at Brivibaplein is “for peace.” In Zedelgem, it is not a monument representing 12,000 poor Latvian Waffen SS souls that should be honored, but instead the memory of the more than 100,000 Jewish victims of that horrible barbarity in Latvia with a plaque bearing as epitaph “For us, all of Latvia is a huge cemetery – a cemetery without graves or gravestones,” as the author of integrity, Max Kaufmann, put it in his Churbn Lettland: the Destruction of the Jews of Latvia.