[UPDATE]

OPINION | LITVAK AFFAIRS | LITHUANIA

◊

by Dovid Katz

Note: An earlier version of this comment appeared on Dovid Katz’s personal Facebook page on 31 Dec.

◊

Each year on New Year’s Eve, when the clock strikes midnight (Vilnius time), our Defending History community publishes its Person(s) of the Year, in most years, and this year once again, chosen from among the most inspirational and eternal of Lithuania’s 20th century heroes: the amazing people who risked everything, starting with themselves and their children and families, to just save a Jewish neighbor and fellow citizen who was targeted for death by the Nazis and their local collaborationists and lackeys. Most years, and this year again, we are fortunate to have an authoritative summary of the achievements of the folks we are honoring prepared for the Persons of the Year series by Danutė Selčinskaja, longtime director of the Project for Commemoration of Rescuers of Jews at the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History in Vilnius. With brevity, authority and humanity, Danutė tells the tale of our 2022 Persons of the Year: Tadas Pocius and Barbora Urbonavičiūtė-Pocienė; Antanas Volskis and Stanislava Volskienė;Leonas Vaidotas and Stanislava Vaidotienė — all of the tiny speck of a village Karalgiris… All simple people of the land whose heart and soul stood entire heavens and firmaments above so many with education, jobs, money, authority, and all the rest.

See Defending History’s Persons of the Year

This year, I had the additional personal joy to learn that the Lithuanian Rescuers chosen to be our Persons of the Year 2022 are those that rescued from certain death my own mentor, editor, teacher and friend from the years of my New York youth (and beyond), Berl Kagan (known as Berl Kahn), and his wife, along with the small group of friends with whom they escaped the Kovno Ghetto.

Now Berl Kahn (1908-1993) was not just any old Litvak: he created and published, in Yiddish, the one-volume encyclopedia of Jewish towns and villages in interwar Lithuania (N.Y. 1991) that remains a classic. It is available online and can be found on the book market (Berl Kagan, Jewish Cities, Towns and Villages in Lithuania. Historical-Biographical Sketches, N.Y. 1991. 805 pp folio [791+v+ix]).

Alas, this indispensable Litvak resource has been shamelessly cannibalized and plagiarized by unscrupulous hacks more than once. It is high time this classic be produced in English in an edition authorized by his heirs. By contrast, an authorized Lithuanian translation was indeed commissioned by Vilnius’s beloved Center for Jewish Culture and Information, thanks to Algis Gurevičius, and completed by Goda Volbikaitė; hopefully it will be published one day soon, individual town entries can sometimes be obtained online, please contact the Center.

Berl Kahn also coedited the classic Yiddish yizkor book for Lithuania (“Líte”, founding editor Mendl Sudarski, 2. vols.), and edited various yizkor books, including the one for Suvalk (Suwalki).

Berl Kahn also edited the final volume of the eight-volume encyclopedia of Yiddish literature, alone produced a ninth volume of addenda (N.Y. 1986), and at the time of his death was nearing completion of a second volume of addenda. Another of his published works was a huge compendium of prenumerántn (pre-publication subscriptions to enable Hebrew and Yiddish books to appear), which provides a vast resource for local Jewish culture going back generations.

To tell the truth, I knew Berl Kahn as an exacting editor, teacher and boss (I worked for him in my student years, writing biographies for the encyclopedia volumes he edited). Upon his death, I wrote a short memoir cum obituary that appeared in 1993 in Itche Goldberg’s New York magazine Yídishe kultúr (“Der sóyfer iz shoyn oykh nitó” in the July-August 1993 issue [vol. 55.4], pp. 54-57). A PDF is available online. I mention there that he had also written a Holocaust memoir, but it was years later that I actually read Kahn’s Yiddish book, “A Yid in vald” (A Jew in the Forest, N.Y. 1955). If I’m not mistaken, it was my first Vilnius mentor, Prof. Meir Shub, founder of post-Soviet Judaic Studies at Vilnius University, who gave me the book after I told him about my having worked with him in my student years. I was shocked that this “shtreynger Litvak” (strict Litvak) Berl Kahn, whose encyclopedias were full of facts, facts, facts, could write such an intimate work of the heart. The one scene that kept returning to me over the decades was at the end. The Soviets (the only force seriously fighting the Nazis in Eastern Europe) come and liberate the surviving Jews in hiding in the summer of 1944. They are free! But at that moment, Berl finds it difficult, for a while even impossible, to say farewell to the simple Lithuanian village folk who risked everything to hide him and his little group all that time to feed and protect them, to be on lookout day and night, to save their lives to take them in as true members of the family in a profound sense of the concept.

Indeed, the recent (2019-2022) history of the English translation commissioned by the Kagan (Kahn) family of A Jew in the Forest, which was translated by Max Rosenfeld in 1996 is itself very important. When Kagan’s nephew Marc Katz, working with his daughter Miriam Kagan Lieber, visited Vilnius in 2019 and presented Ms. Selčinskaja and her colleagues with a copy of the English translation, Ms. Selčinskaja and her team got to work and found the individual rescuers cited hundreds of times in Berl Kagan’s book (where they are referred to by first names only), as well as their grandchildren and relatives who are now alive in the same area where the rescue of the group of Kovno Ghetto escapees was meticulously planned and carried out by their recent forebears over the entire period between the escape from the ghetto in 1943 and liberation by the Soviet army in 1944. This is one of many major discoveries of rescuers by Danutė Selčinskaja based on meticulously copious and clear testimonies such as the book of Berl Kahn.

Many years after Berl Kahn had passed away and I was settled in Vilnius in the aughts, one of my closest friends was Berl Glazer (1924-2013) who lived around the corner from me, Vilnius’s (more or less) only prewar Litvak Orthodox Jew at the time. See in LYVA under his native town Namóksht (Nemakščiai), some of the interviews with him. I’ll never forget nearly falling out of my seat when he told me that his best teacher before the war was a young educator from Kóvne who had been sent to Namóksht to teach. His name? Berl Kahn (and Kagan’s Namóksht stint as teacher is indeed mentioned in his biography). Being a Litvak myself, I insisted Berl Glazer give me a description of his childhood teacher, and by jove, it was definitely the same Berl Kahn….

Returning to the main point, our naming as people of the year those 1943-1944 angels of a village called Karalgiris:

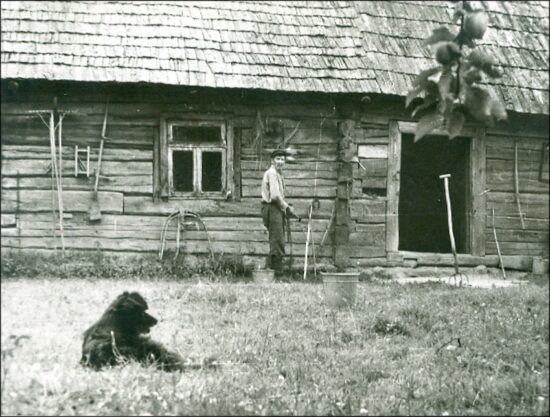

Tadas Pocius and Barbora Urbonavičiūtė-Pocienė; Antanas Volskis and Stanislava Volskienė; Leonas Vaidotas and Stanislava Vaidotienė. Well, Danutė’s article has, as ever, photos of the rescuers and the rescued. Still, there is one photo that in its own haunting way tells the story of the Rescuers with singular dramatic resonance. That’s the photo of Leonas Vaidotas going about his daily life near his house, the simple wooden kháta that became in his blessed and almighty hands the vessel of lifeblood for his fellow human beings, fellow Lithuanian citizens, a house of refuge from certain death. This is what a magnificent humanist hero looks like…