O P I N I O N / E Y E W I T N E S S R E P O R T

by Geoff Vasil

In the tradition of totalitarian societies, a certain segment of the Lithuanian political spectrum found it inconceivable there should be protests over the repatriation and reburial of Juozas Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis, the Nazi puppet prime minister of Lithuania in 1941.

The reburial ceremonies took place earlier this year with state support and accompanying civil and church ceremonies.

DefendingHistory and a number of Lithuanian politicians, writers and public figures protested against the reburial, while many “formers”—foremost former Lithuanian president Valdas Adamkus, who himself served under Nazi command in Lithuania in 1944—conspicuously attended the reburial in Kaunas.

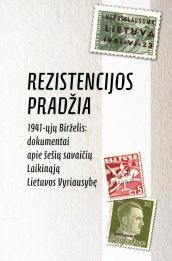

The “protests” this series of events occasioned—again, only in cyberspace and print—seem to have struck a nerve with the Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis supporters, so much so that MEP Vytautas Landsbergis, usually credited with leading Lithuania out of Soviet captivity, has seen fit to issue a rebuttal in the form of a small book, called Rezistencijos pradžia. 1941- ųjų Birželis: dokumentai apie šešių savaičių Laikinąją Lietuvos Vyriausybę [“The Beginning of the Resistance – June of 1941: Documents on the Six-Week Provisional Government of Lithuania].”

The “protests” this series of events occasioned—again, only in cyberspace and print—seem to have struck a nerve with the Ambrazevičius-Brazaitis supporters, so much so that MEP Vytautas Landsbergis, usually credited with leading Lithuania out of Soviet captivity, has seen fit to issue a rebuttal in the form of a small book, called Rezistencijos pradžia. 1941- ųjų Birželis: dokumentai apie šešių savaičių Laikinąją Lietuvos Vyriausybę [“The Beginning of the Resistance – June of 1941: Documents on the Six-Week Provisional Government of Lithuania].”

Landsbergis chose to personally launch the book at the House of Signatories in Vilnius on 11 September 2012. This venue is a museum and event space centering around the building where Lithuania declared independence in 1918.

◊

The conference hall on the first floor of the building was full to overflowing before the first speakers began the book presentation. Vidmantas Valiušaitis, the journalist who presided over the “academic conference” held at Kaunas city hall to honor Brazaitis earlier in the spring, acted as master of ceremonies here, too. Historian Kęstutis Girnius, infamous for his glorification of the local Nazi collaborators of 1941 (and just a few weeks ago announced as a new member of the state-sponsored “red-brown commission”), spoke first, followed by historian Mindaugas Tamošaitis, who delivered a series of facts and opinions in a staccato, rapid-fire fashion.

When Landsbergis began to speak the ambient silence of the audience raised a notch and the listeners became attenuated. This was the man they came to see. Landsbergis seemed to know this and teased the large audience by speaking quietly.

The substance of what was said from the podium was that certain “clichés” had been repeated in the denunciations of the Brazaitis ceremonies, clichés which needed addressing. Girnius distanced the Provisional Government from the Lithuanian Activist Front, although both were part and parcel of the same movement started by the same individuals. Paraphrasing Tamošaitis, he felt Brazaitis had been targeted unfairly, but that Kazys Škirpa, the Provisional Government/LAF’s first choice to lead the Nazi puppet government, had been pursuing personal ambitions and sought to make a career for himself within the Nazi hierarchy. Landsbergis claimed the very act of proclaiming the Provisional Government went against the desires of the Third Reich, and therefore it had been an anti-Nazi organization from its very inception.

Girnius and Landsbergis claimed the damning Provisional Government (PG) resolution for setting up a concentration camp for Jews in Kaunas and signed by Brazaitis was probably a misunderstanding, and that “concentration camp” probably had a different meaning for the Lithuanians from the sense in which the Nazis used it. Without addressing the real etymology of the term—it first came into English in parliamentary debates about the Boer War in South Africa in 1901, but derives from the reconcentrado camps set up by the Spanish to deal with the Cuban guerillas—the historical argument against Lithuanian understanding of the term was that there had been something called a concentration camp already in operation in Lithuania before the Nazi invasion, a concentration camp which, presumably, was much kinder and gentler than the Nazi conception.

Landsbergis quibbled over why the PG chose the Seventh Fort to house a concentration camp in Kaunas, but then admitted Jews had been murdered there, rendering his own argument purely semantic.

Just before the Q&A Valiušaitis took the opportunity, as he had done as well at the Kaunas “academic conference,” to make some points of his own. He tried to make what is usually now called a “straw-man argument,” but failed. He claimed that nay-sayers during the Brazaitis reburial controversy had managed to post on the internet an audio recording of the LAF’s Prapuolenis addressing the public in Kaunas over the radio and proclaiming the existence of the PG. In fact, as far as I know, no one did re-post this during the Brazaitis controversy, but such a recording reportedly does exist and a copy was obtained by a now-defunct Lithuanian-American magazine several decades ago. Valiušaitis then tried to point out that there was no way to record a radio program in 1941, and therefore the recording must be counterfeit. Of course there were ways to record radio in the 1940s, and they were routinely employed by radio stations, including transcription discs and wire recordings. Reel-to-reel recording on Mylar tape, of course, did come out of Nazi Germany and became popular in the United States after the war.

Landsbergis and the others also mentioned supposed proof the NKVD and Gestapo had conspired against LAF cells in Lithuania. Landsbergis also said he regretted he had not pressed his father, a minister in the PG, for the full story before his father died. His father signed the notorious PG resolution “Regulations on the Situation of the Jews,” which, of course, meant something else entirely. A concentration camp is not a concentration camp, antisemitic laws aimed at the physical destruction of Jews aren’t antisemitic, the documents lie, the eye-witnesses are KGB agents and besides, the Provisional Government didn’t really have any power, anyway.

It all seemed to play well to the audience of true believers, and this was the point of the presentation and probably the book as well: to maintain plausibility in denying what really happened in Lithuania in June, 1941, using sophistic arguments and speculation. The target audience didn’t seem to include foreign observers, this was and is intended for domestic consumption.