Some eighty people gathered at midday today, in an eerie mix of wind and autumn sun, at the forest mass grave memorial site just outside the town once known in Yiddish as Svintsyánke (or Nay-Svintsyán; now Lithuania’s  Švenčioneliai, interwar Poland’s Nowo-Święciany). Such is the custom every year on the first Sunday in October, to remember the eight thousand Jewish civilians murdered there after a gruesome ten days of imprisonment, deprivation of basic human needs, and torture, in makeshift barracks here at the site, in October 1941. The eight thousand Jews were marched (with the lame and the old transported on wagons) from their hometowns in the area to the site on September 27th. They were all shot over a two-day period on the 7th and 8th of October 1941.

Švenčioneliai, interwar Poland’s Nowo-Święciany). Such is the custom every year on the first Sunday in October, to remember the eight thousand Jewish civilians murdered there after a gruesome ten days of imprisonment, deprivation of basic human needs, and torture, in makeshift barracks here at the site, in October 1941. The eight thousand Jews were marched (with the lame and the old transported on wagons) from their hometowns in the area to the site on September 27th. They were all shot over a two-day period on the 7th and 8th of October 1941.

About half of the victims were the Jews of Svintsyán itself (now Švenčionys, some 47 miles northeast of Vilnius). The remainder were from an array of towns and villages in a circumference straddling the current Lithuanian-Belarusian border. In addition to Svintsyán and Svintsyánke, the Jewish populations of Dugáleshik, Haydútsetshik, Ignalina, Podbródzh, and Tseykín were among the victims.

The murderers were virtually all local volunteers and auxiliaries working under Nazi command, but with rather more autonomy of action and cruelty than in many other locations, where the mass shootings generally occurred upon arrival at mass grave sites.

The mass grave site is hard to find. It is not marked at all from any main road. The small stone marker installed as part of a British-funded project is located well within the forest and is of no use in finding the site from any paved road in the area.

The mass grave site is hard to find. It is not marked at all from any main road. The small stone marker installed as part of a British-funded project is located well within the forest and is of no use in finding the site from any paved road in the area.

There is however a single wooden marker in the (culturally inappropriate) shape of a cross near the side road where the wooded area begins, which says in Lithuanian: ‘Site of Mass Murder’. The culturally appropriate and dignified proper multilingual monuments are all located at the mass grave site itself.

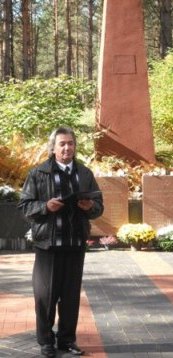

The ceremony was ably organized and chaired by Meyshke (Misha) Shapiro of Podbródzh (Pabradė), who is the head of the tiny Jewish community that remains in the region, an affiliate of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. Mr Shapiro conveyed the greetings and words of support from the leaders of the community in Vilnius, Dr Shimon Alperovich and Ms Faina Kukliansky.

The ceremony was ably organized and chaired by Meyshke (Misha) Shapiro of Podbródzh (Pabradė), who is the head of the tiny Jewish community that remains in the region, an affiliate of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. Mr Shapiro conveyed the greetings and words of support from the leaders of the community in Vilnius, Dr Shimon Alperovich and Ms Faina Kukliansky.

Mr Shapiro is the son of the late Ziske Shapiro (1918-2003), a beloved personality in the region, who was born in Ignalina, one of the towns whose Jewish population was force-marched here under brutal armed guard to this mass grave site known as Poligón (a term deriving from its pre-war Polish-era use as a military base). Also sorely missed was the late Blumke Katz (1913-2006), a veritable living encyclopedia of the Jewish culture of Svintsyán and its environs. After Lithuania gained its freedom from the Soviet Union, she embarked, in a one-woman campaign, on a years-long effort to have this gravesite properly marked in addition to discovering, with the help of local witnesses, many smaller mass graves throughout the region.

Speakers at the commemoration ceremony included Vytautas Vigalis, mayor of Švenčionys; Piotr Vdoviak, counselor at the Polish Embassy in Vilnius; Fania Yocheles Brantsovsky, Vilna Ghetto survivor and partisan veteran; Natalija Alinauskienė, high school principal in Pabradė; Valeri Yemelianov, a leader of the Polish community in the region; Dovid Katz of the Litvak Studies Institute, this journal’s editor, who read a short poem by his late father, Svintsyán born Menke Katz (1906-1991); a group of children from the Russian speaking school in Pabradė, and, an instrumental quintet from Pabradė’s musical school. Greetings were conveyed from the ambassadors of Norway and the United Kingdom.

Misha Shapiro, chairing the event, paid tribute to three landslayt, natives of Svintsyán, who died since last year’s meeting here: Sonia Boyershtein and Rokhl Matzkin in Vilnius, and Jacob Abilevitch in Israel.

The mass grave at Poligón is very long.

The mass grave at Poligón is very long.

It has been a tradition since the war that at the end of the annual commemoration, the assembled walk all around it, on the way stopping to reflect at two very different trees. At one end, there is a tree that the murderers used to smash the heads of babies and toddlers against in order to save ammunition. It was left with a visible indent from the many children’s heads slammed against it. It used to be marked by a sign that disappeared however some years ago. A second tree, near the other end, is a birch planted by Blumke Katz after the war, near the spot where she imagined her mother, Frumke, fell into the pit, wounded and naked, to be buried alive along with all the other Jews of the town and its region.

A colorful personality who passed away in recent years was Shimke Gurvitch (1913-2006), who was the last in a long line of wagon drivers (after the war, which he survived by serving heroically in the Soviet army’s 16th Division, he was a bus driver). He was always proud that his children spoke Yiddish. His daughter, Riva Gurvitch Davidovits, and her husband Abraham, came specially from Stockholm, as they do every year. Son Moise (at right of photo), an engineer, and his family from Vilnius were on hand as well.

A colorful personality who passed away in recent years was Shimke Gurvitch (1913-2006), who was the last in a long line of wagon drivers (after the war, which he survived by serving heroically in the Soviet army’s 16th Division, he was a bus driver). He was always proud that his children spoke Yiddish. His daughter, Riva Gurvitch Davidovits, and her husband Abraham, came specially from Stockholm, as they do every year. Son Moise (at right of photo), an engineer, and his family from Vilnius were on hand as well.

As is the custom, the region’s tiny handful of Jewish survivors and a few guests then adjourned to Svintsyán’s warm-and-welcoming Café Arka, to talk about old times, and about how the memory of the town’s annihilated Jewish people and their lore and culture can somehow, somewhere, be preserved.

Today, three Jews live in Svintsyán: Meyshke (Misha) Preis, a native of Kovno (Kaunas), who survived the Kovno Ghetto, Stuthoff and Auschwitz; and his wife Zoya, who was a ‘rescue child’ given to a Polish couple just before her birth parents perished.

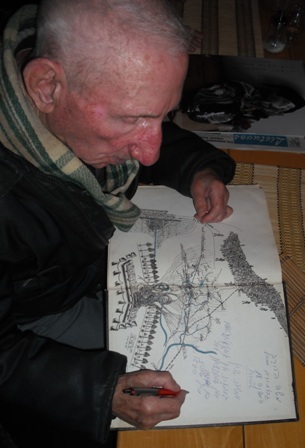

The third is Meyshke (Misha) Shein, a native of Duksht, near Ignalina, who grew up here in Svintsyán. He survived the war by fighting with the Soviet army and is a much decorated veteran in the battle against the Nazis. Virtually his entire family was murdered and lies buried here at Poligón. He is verily today the last Jewish Mohican of Svintsyán, who grew up here and still lives here. One person.

and lies buried here at Poligón. He is verily today the last Jewish Mohican of Svintsyán, who grew up here and still lives here. One person.

At the café following the forest ceremony, Mr Shein, in his late eighties, was happy to comply with a request to write his family data into a copy of the large Svintsyán yizkor book (commemoration volume) that appeared in Tel Aviv in 1965, and which contains eyewitness pitside memoirs, in Yiddish, that remain to be translated, so that the final days of Svintsyán’s Jews will finally be known to readers of other languages. He chose the page which contains an artist’s conception of the great Exodus to Death of Svintsyán Jewry: the long forced march from a famous Jewish town of hundreds of years’ standing, to the long-long death pit at Poligón, right across the bridge that traverses the Zhemyáne River.

♦

[Sources on Jewish Svintsyán and its Holocaust history: 1, 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7.]