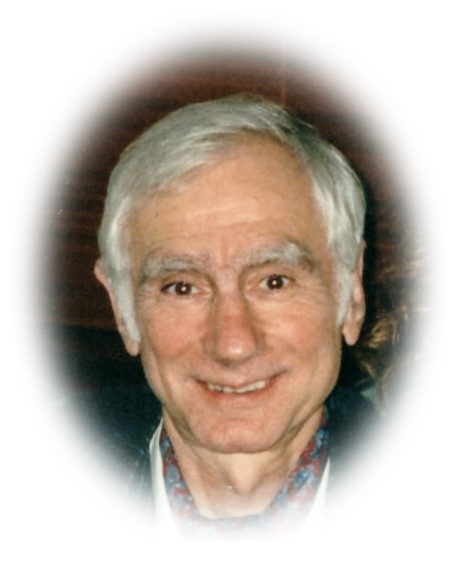

VILNIUS—While some biographies cite 1937 as the year of Professor Valerijus Čekmonas’s birth, many of his numerous students and admirers both here in Vilnius, and internationally, who were heartboken by his untimately death in 2004, are taking the 1936 year as definitive and celebrating his life this season on the occasion of what would have been his eightieth birthday.

A master philologist and dialectologist, and at the same time an unwavering staunch humanist, Valerijus Čekmonas (Valery Chekman) demonstrated how unswerving loyalty to modern Lithuania’s independence and democracy is wholly compatible with love of the region’s many cultures and languages. Always seeking to expand the tent with new talent, and bring under the roof of philology and cultural studies people who may disagree with each other vehemently on all sorts of other questions, he singlehandedly made the Philology Faculty, and at times the History Faculty, of Vilnius University into internationally acclaimed centers of academic excellence, diversity and tolerance that were pioneering the way for minority studies far beyond the borders of Lithuania. Well aware that ultranationalists have a way of sidelining minority cultures and languages, Čekmonas became a champion of Lithuania’s minority languages. He was instrumental in setting up the Center for Stateless Cultures in 1999 that in one fell swoop brought Karaimic, Roma, Russian-Old-Believer, Tatar, and Yiddish languages and cultures into Vilnius University in a partnership with the Soros Foundation and others. About a year later, he became a champion of the idea of a Yiddish Institute at Vilnius University, and was one of the prime personalities who enabled it to happen, sparing no effort in running around selflessly between administrators, donors, academics, politicians — you name it, he went there until the answer was “Yes”. . . He had a special place in his heart for the endangered Yiddish language in the region and for the sensibilities and dignities of the rapidly fading generation of Holocaust survivors. He spared no effort to help the progress of the ongoing informal and unfunded Atlas of Lithuanian Yiddish.

That Vilnius University was blessed with a Center for Statelss Cultures and a Vilnius Yiddish Institute is in both instances largely attributable to the energy, dedication and love of small cultures of that one philology professor, Valerijus Čekmonas. In the politically charged philological field of Balto-Slavic studies, Čekmonas was often the one voice of tolerance and respect for “both sides of the argument” (rather than a one-sided “loyalty test” political approach), as befits academic discourse in the framework of a great modern liberal university. His tolerance extended to political tolerance and understanding per se. And, it extended to personal courage. For all his hatred of Soviet oppression, he was until his dying day proud of his father who gave his life in the Red Army fighting Hitler, and would always dress up in his uniform and celebrate in style on May 9th, the anniversary of the victory over Hitler as celebrated in eastern Europe (it’s May 8th in the West). In fact, Valery’s practice was to invite young Lithuanian philology students to his home on May 9th, and to explain how the struggle to bring down Hitler and Nazism was a struggle for all of humanity, and for their generation too.

For all his love of his adopted country, Lithuania, and for the decades he spent mastering the intricacies, dialects and history of the unique Lithuanian language, and the risks he took supporting Sajudis during the days of the crumbling Soviet Union, there were always ultranationalist detractors who would not trust someone of foreign birth whose native language may have been Russian, who saw something suspicious in his embracing, particularly, of Jewish and Roma culture. When he was named the second director of the Center of Stateless Cultures, one famous Kaunas professor on the relevant Soros Foundation committee protested on the grounds of his “Russian” background (he was in fact born in Ukraine, and despite his surname ending in -man, had no personal Jewish background).

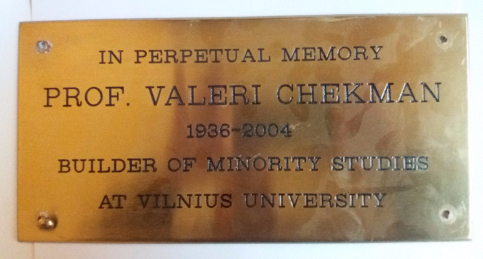

After the shock of his acute illness, which he bore with dignity and even bursts of extraordinarily courageous wit, followed by his passing, a number of the scholars he had helped become acclimatized in these new institutions at Vilnius University passed around the hat to enable two bronze plaques, one in Lithuanian, one in English, to be struck in his memory and placed in the Yiddish Institute. People of every age and background remember how he reached out to inspire each and every person to help them believe in themselves, to believe that they could and would achieve things that would make a difference, both for academia and the wider world. And he always did it with remarkable multilingual humor and good will that could of an instant split an ice-barge.

The Defending History community, which would not now exist in Vilnius if not for the years of help and encouragement from Professor Valerijus Čekmonas, salutes Vilnius University on holding a conference to mark what would have been his 80th birthday (conference program [also here]). We deeply regret, however, that all those removed from the university or effectively demoted in ultranationalist purges after his death, have been excluded from this conference in his memory. Those purges occurred in the wake of the absurd state prosecutor’s accusations of “war crimes” against the Yiddish institute’s Holocaust-survivor librarian who was the only member of her family to surive thanks precisely to her joining the anti-Nazi partisans who remain a pride to the free world. She continues to be defamed by the same state commission that purged the Yiddish institute and provided its Yiddish-free director. The international requests for apologies to all five defamed survivors continues to present the nation’s leaders with a golden opportunity.

Few of Professor Čekmonas’s closest students, colleagues, academic followers and admirers seem to have been invited to read papers at the conference in his memory.

In fact, there seems to be a negligible minimum of academic papers (euphimism for “absolute zero”?) in the fields of Karaimic, Roma, Tatar and Yiddish philology (none of which would have existed at Vilnius University, but for Professor Čekmonas). For that omission, dear Valery is spinning in his grave — or, we like to think, dancing with a toast in hand, high up in the Heaven of Philology — and asking the conference organizers: “Hey, chebra, but why, what’s up?”

As for the English-language plaque commissioned and erected after his death, perhaps the conference convenors could now at least arrange for replacement of three of the four bolts that have since been removed for other purposes by the new masters of the Yiddishless “Yiddish” institute, and give it a nice, fresh clean-up to mark dear Valery’s 80th? As for the matching Lithuanian-language plaque, the conference may undertake to locate its whereabouts and rededicate it on the occasion of Professor Valerijus Čekmonas’s eightieth birthday.