◊

in memory of

Roza Bieliauskienė (1946-2023)

◊

She died faster than a match burns out. Dumbfounded, we are trying to understand her place in our lives, and in Jewish culture, to which she devoted so much energy. The Jewish Museum in Lithuania has a long-suffering history. It burned, and was plundered, and ceased to exist, opened and closed many times… There were always experienced workers, Torah connoisseurs who knew Hebrew and, of course, Yiddish.

And suddenly, after World War II, only a few of these specialists remained alive. And in 1949 the museum, where writers, journalists and other cultural figures had already settled, the Soviet authorities again closed the museum and dispersed its collections, all that had miraculously survived during the war years, distributing it to various museums in Lithuania. Jewish culture was rapidly destroyed. Yiddish writers either went to camps, like all “rootless cosmopolitans,” or mastered some applied professions, while others began to write in Lithuanian. In a rare Jewish family did they continue to speak máme-loshn (Yiddish). Parents among themselves — yes, but with children in Russian or in Lithuanian.

The great exodus was just brewing, and it never occurred to anyone that there would be an opportunity to break out from behind the Iron Curtain. But yet that hour had come. Slowly, with a creak, the curtain began to rise. The Jewish survivors of the Holocaust were relocated from their places, repatriated with great difficulty, placing the surviving relics, dishes, blankets in specially knocked together boxes. By that time, Roza had graduated from an engineering university. She had become an expert in the engineering field of jacking! At home she, born in 1946, spoke Yiddish with her mother, which was rare. She married the son of a Lithuanian and a Jewess, which means a Halachic Jew.

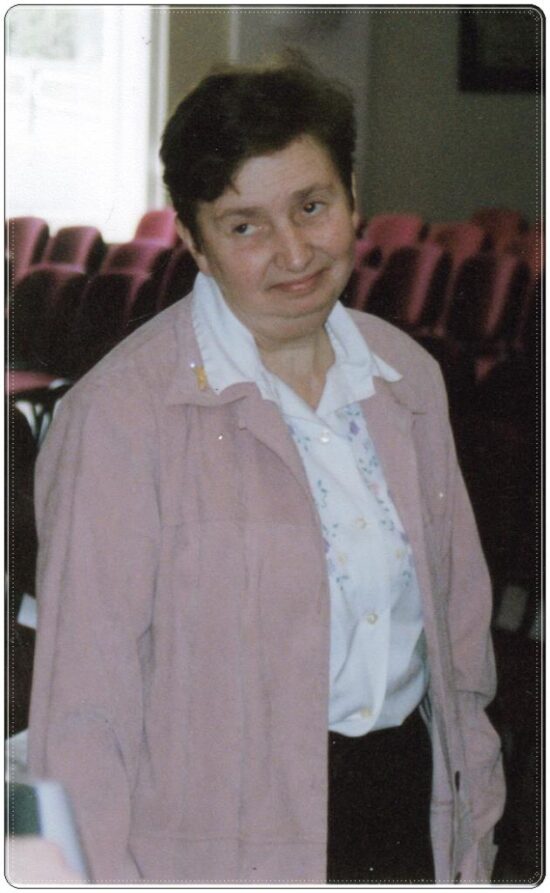

Roza Bieliauskienė during her time as curator of Lithuania’s Jewish museum, at its Naugarduko Street headquarters in Vilnius. Photo courtesy of the Vilna Gaon Museum of Jewish History.

The new Jewish museum in Vilnius opened in 1989. And then it turned out that there were simply no specialists in Jewish culture and history. Engineers, translators from foreign languages, physicists, teachers of the Russian language were among those who began to work in the museum. The historical department was headed in different years by a publishing worker, a biology teacher, and other people. The Holocaust Museum (“the Green House”) was run by a female lawyer who was an English speaker. All of them were far from knowledge of Jewish history and culture, but had a great and often tragic experience of the Shoah. The only professional museum worker and historian turned out to be a former employee of the closed Museum of the Revolution, but he was neither a specialist in Jewish history nor an expert in the language. Rosa Beliauskienė, a jacking engineer, became the curator of the museum’s holdings.

The exhibits arrived slowly. In antique shops, one could still buy Sabbath candlesticks, and other ritual and household items. Most often they were handed over for sale by those who took them from Jewish homes during raids. There were very few paintings, but there were plenty of photographs, mostly of unidentified persons, prisoners of the ghetto. Many of them are not identified to this day. Roza was a strict leader, no one knows where and how she filled in the gaps in her Jewish education. I remember that people rarely entered the premises of the holdings, and only on a serious occasion.

Roza was one of the few museum staff able to read Yiddish text. After retiring, she continued her research activities, searched for texts for publication, and translated. This was no easy task, since she did not have professional training in literary work. She approached everything with hard work and perseverance. These qualities were admirable. I was also a person of an outside profession in the museum, it was here that the meaning of the profession declared in my diploma was revealed to me: literary translation, literary work. I understood what a literary work is. It means everything! This is a historical and biographical study, this is a complete coverage of sources and, finally, a convincing embodiment.

From Roza we received translations of the stories of a previously unknown remarkable prose writer, Borukh (Baruch) Halpern, who worked in an engineering office, where nobody knew about working with a real writer. I have edited her translations of the short stories by Isaac Meir Dik and Jacob Dineson. I keep in draft a translation of an excerpt from Leyzer Ran’s book Ashes of the Jerusalem of Lithuania. We talked a lot about this author. It was difficult and exciting to translate the story of Dovid Katz, Journey to Levóneshok (Levoniškės), where there is both philosophy and symbolism, the colossal erudition of the author, and a large dose of humor. For a colleague, an art historian, Roza studied all the huge press of the 1920s and 30s, translating materials about Jewish art during this period of huge development of Jewish culture.

We lived across the yard from each other. We often met in the local grocery, then at the bus stop. Somehow it turned out that everyone knew about each other. I grumbled at her for exhausting herself with hard work. Roza thought she was doing well. That last Sunday, 29 January 2023, she was supposed to teach a Yiddish class at the community center. She didn’t show up.

If she failed to come, it means that something terrible, irreparable, happened.

We knew our Roza.