LATVIA | MEMOIRS

by Monica Lowenberg (London)

◊

“To remember would be to remember their life and their death. But that memory is forbidden, and one is afraid of thinking that something exists that is worth remembering, when one does not manage to remember this. All memory seems to be, ought to be, memory of that, all forgetting, forgetting of that. Like an unchanging symptom, the repeated pain caused by the realization that one constantly forgets places, moments, people, is like the simple reflection of the pain that finds in them its true name.”

N. Fresco, Remembering the Unknown

On the 18th of February 1960 my late father Ernest Lowenberg went to the German embassy in London to declare his brother Paul Loewenberg and Latvian born father David Loewenberg/Levenbergs dead.

Mein Vater, David Loewenberg, geboren am 29.11.1877 (sic 1875) in Libau (Lettland) fluechtete am13 Maerz 1941 von seinem letzten Wohnort Berlin NW87, Altonaerstrasse 16, nach dem Osten. Seither ist er verschollen. Alle meine Bemuehungen , besonders nach Kriegsende, etwas ueber das Schicksal meines Vaters in Erfahrung zu bringen, blieben erfolglos. Es ist daher mit Sicherheit anzunehmen, das er im Zusammenhang mit den Ereignissen des Krieges ums Leben gekommen ist. Ich beantrage daher seine Todeserlaerung von dem gesetzlich vorgeschriebenen Zeitpunkt und gehe davon aus, dass dies der 31.12.1945 ist.

Mein Vater hatte zur Zeit seines Todes die lettische Staatsangehoerigkeit.

◊

Translated:

My father, David Löwenberg, born on 29.11.1877 (sic 1875) in Libau (Latvia) fled on 13 March 1941 from his last residence in Berlin NW87, Altonaerstrasse 16, to the East. Since then, he is missing. All of my efforts, especially after the war, to establish what happened to my father have been unsuccessful. It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that he died during the war. I therefore request that his date of death be officially recognised as being the 31.12.1945.

At the time of his death, my father was of Latvian nationality.

My father never spoke to me about my grandfather or even gave me his name, that is not until 1992, when I was almost 30. I knew my grandfather’s name through snippets of adult conversation whispered late at night when it was assumed I was asleep, nearly always in German but I never personally probed my father further on the subject. It was an unspoken taboo. So my grandfather’s life and that of my Latvian Jewish family was never investigated, inquired about or indeed spoken about. Instead we buried them in a sea of silence where waves of grief quietly beat their fate.

See also Monica Lowenberg’s article on “The Long Arm of Antisemitism in Latvia”. Monica Lowenberg author’s section.

Until 2011 when my father asked me to go to Riga in Latvia and find out what had happened to them once and for all. My father had miraculously recovered from bowel cancer in 2008 and was told that he could have another five years to live; on hindsight it is clear that he had wanted me to help him tie loose ends up; he had nothing more to lose.

The Cold War was over. Since 2004 Latvia has been a member of the EU. Numerous visitors came to the small Baltic country to admire its quaint villages and richly ornate art deco buildings in the capital of Riga, the capital of a country whose history has been over the centuries forged in blood, with parts or all of its territory nearly always under the rule of German, Polish, Swedish or Russian invaders. [1]

◊

Whilst looking in the state archives in Riga, in the autumn of 2011, I discovered that my grandfather had had eight siblings. Like him they had all been born in Libau between 1867 and 1879. It was a moving and yet simultaneously frightening revelation. With their birth records in front of me it was clear that they had lived but it was at the same time clear that they and their children had not survived, for no one, no one at all had ever contacted my father over the years of searching for his father and brother. My father never changed his name so that relatives, perhaps just one, could find us. And with Google in 1998 I searched every week for family for my father and put out search notices on websites which gave our contact address. No one came. However, here in the archives, here they were, their births neatly recorded in black ink, in old Russian script. There was Rael who had tragically died in 1869, like many children at the time, of croup when a few months old. And then there were the two elder twin brothers Abraham and Moyshe who, like my grandfather, left Latvia at the turn of the century, prior to the first world: Abraham for Tehran, Moyshe for Paris. I could not find any birth record for my grandfather’s beloved younger sister Gertrude who married a solicitor called Schnitzler, moved to Geneva and later died there of natural causes around 1937. However, the other siblings whom we had never known existed, the sisters Zlato, Rivke, Judith and brother Josef, rose from the sweeping script like a phoenix from ashes.

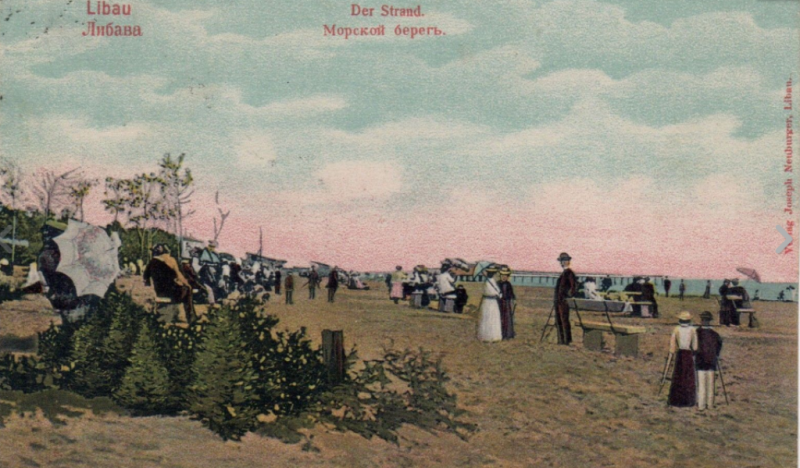

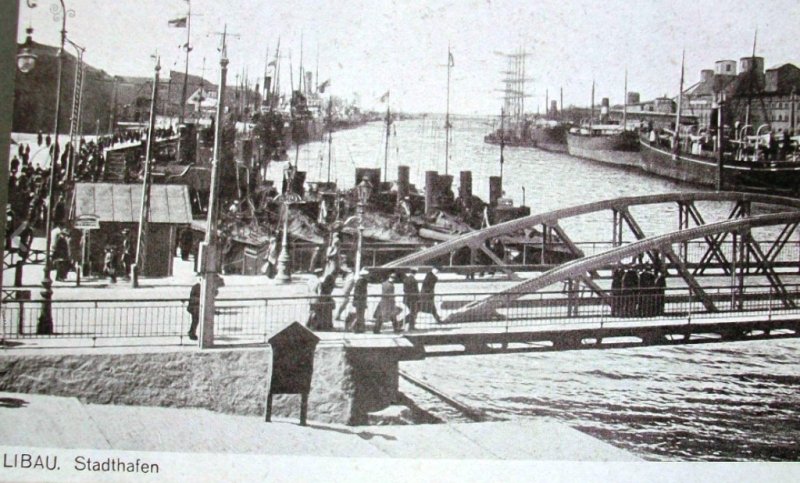

The port city of Libau, as it was known by the Germans, was called Liepāja in Latvian. It was occupied like much of the Baltics by Germany during 1915-18 and 1941-44 and by the Russians in 1940-41 and then again from 1944-91. Whilst under Russian rule, Liepāja became the home base of Russia’s large Baltic fleet and therefore was an area that the German’s deeply prized but were also were deeply wary of. As Immanuel Blaushild recalled,

Libau, founded in 1625, was until 1914 one of the main ports of the Russian empire. Along its spacious harbor there were rows and rows of warehouses where herring from the Atlantic was stored; timber, grain, butter was loaded on ships going to the West. After World War I, with the loss of its huge hinterland, Libau declined, its population was halved to about 60,000, factories stood silent, warehouses empty. During the 22 years of Latvia’s independence Libau was the second largest town of the country.

Compared with Paris, London, and New York, Libau might have seemed just a small provincial nest. But now, thinking back after half a century, we know that Libau was a beautiful city. There was a belt of parks between the town and the sea with its clean white beach.

Summer was a wonderful season. In the park, where mothers wheeled their babies and where lovers sat on benches, there was a fairy tale pavilion and a bathhouse built in neo-classic style. Here Jews would go every Friday afternoon for their weekly bath towards the Sabbath.

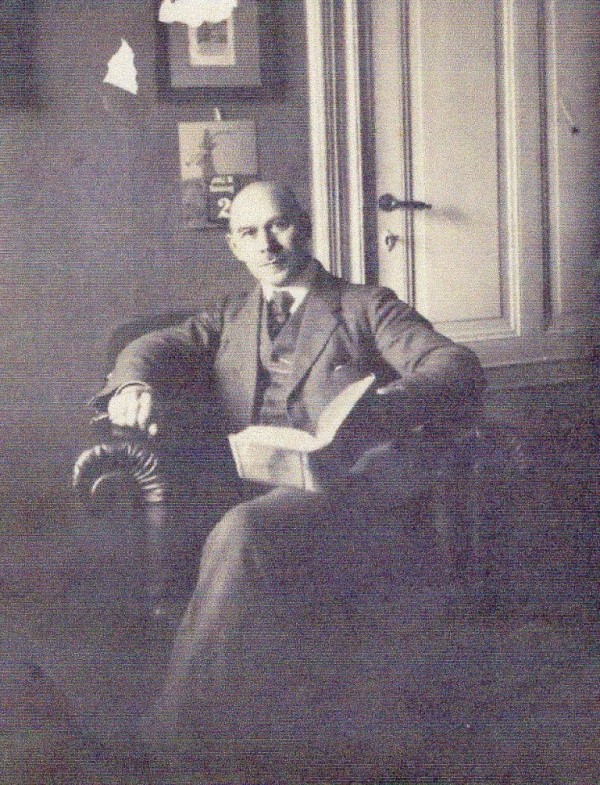

For some strange reason, in my mind’s eye I had always imagined Libau or Liepāja, as being some dark, backwater town by the sea where poor people tried to eke out their living, hobbled around in tattered clothes similar to those in a Brechtian Mother Courage production. I imagined it as a place where my great grandfather, Lazzers Levenbergs, a former soldier for the Russian empire, was content to make a little living out of the furniture shop he ran with my great grandmother Minna Bernstein and probably their children. And yet the few pictures and official documents I personally own of my grandfather reveal a man who lived an assimilated and relatively prosperous life until the Nazis came to power.

According to Feigmanis the custom at the turn of the century for a number of Latvian Jewish families was that they would very often share resources to enable one son, who was academic, to go to university. That honor became my grandfather’s and he went to Dresden to study. He was open to new ideas and even attended the first Zionist conference in Basel in 1897. He spoke and could work in five languages: Latvian, Russian, German, Hebrew and French. Clearly the education my grandfather had been fortunate enough to receive from the Rabbis in Libau, and then in Dresden, had served him well. It is true Libau was a provincial nest in comparison with London where I grew up but it was nevertheless an intellectually vibrant, lively and beautiful town.

After his studies David chose to stay in Germany and became an engineer. He invented an Abfuellmaschine (a machine that would fill bottles and cans with food such as fruit, soup and meat) and moved to Halle an der Saale and then to Berlin where in Berlin-Moabit he set up a factory called Ammendorfer Maschinen und Feilenfabrik Gmbh at Waldstrasse number 24. When the Nazis came to power his Aryan business partner Albrecht did the dirty on him and he subsequently lost his sole source of income. The loss proved too much for his second marriage to my grandmother Marianne Peiser, who after 1935 was unable to make a living as a musician. Economic necessity forced my grandparents to put their two young sons, my father and his brother Paul, into an orphanage , the zweites Juedisches Waisenhaus in Pankow Berlin and in 1939 they divorced. As my father explained:

In 1929 my father went to Berlin. He had for the past five years been separated from my mother, and my brother and I stayed with our father. Shortly after the takeover, my father’s business slowly came to a halt. Financially, it became impossible for him to look after my brother and me and so we were taken to the second Jewish orphanage in Berlin Pankow where I stayed until 1938’.[2]

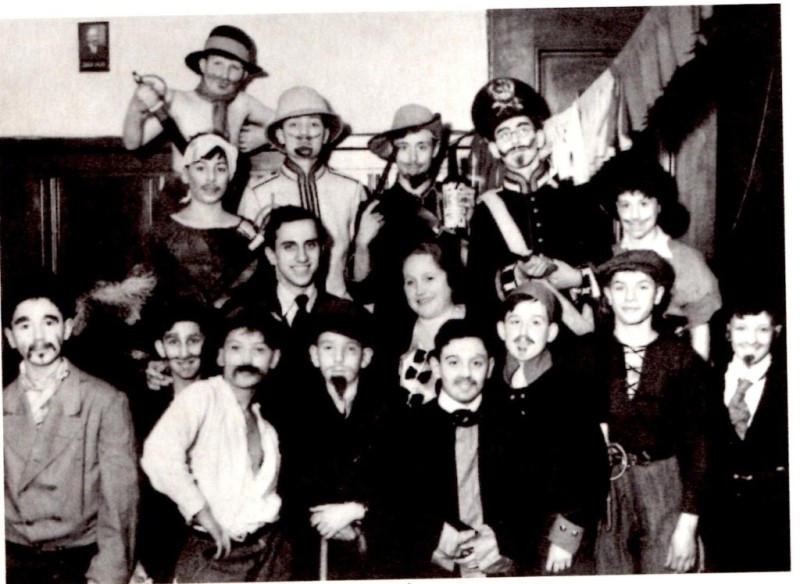

Director Blumenfeld with the little children 1933/34 left Miss Salinger and Siegfried Baruch, directly in front of Baruch, Paul Loewenberg (back row third from the left). Back Herta Kemper. Ernest Loewenberg is in the back row, eighth from the right.

◊

Paul (left) and Ernest (right) with their mother Marianne Loewenberg nee Peiser 1932 age 11 and 10. Paul was sent to the Riga ghetto age 19.

◊

Purim 1937 in the Jewish Orphanage with the cantor Julius Stolberg second row, to his left Frau Goldbarth. Ernest Loewenberg top row, far right dressed as an admiral in Schillers ‘Die Raeuber’ (The Robbers).

Many years later in 1992, after I noted scars on my father’s back, my father recalled to me his father’s angry outbursts and how David refused to say goodbye to him when he left for England with ORT on the 26 August 1939, three days before the outbreak of war. On hearing this story David seemed a monster who had terrorized his family but as I have grown older, I can now see he was simply a man, walking a tightrope that would soon collapse.

On the 26 of September 2012, the Baltic wind blew a letter to my door and with it my father’s search for his father ended. Dated the 5 September 2012 and from the Russian Federation, it stated that the Russian Government admitted to having falsely accused David Lowenberg/Levenbergs of having been a spy after having just escaped Nazi Germany and arriving in Moscow in March 1941 to head a machine tool factory. For three months he was imprisoned in a building annexed to the infamous Hotel Lux. Later in the July of 1941, David Loewenberg was deported to a gulag in Krasnoyarsk region, Siberia. He survived one winter and died age 67 on 26 May 1942 in Novosibirsk Oblast. Little did he know that he would never see his family again or that 47 years later on the 28 November 1989 his file would be reviewed by the military prosecutor’s office of the Moscow Military District and his name would be rehabilitated. It was a small token of comfort but nothing more. ‘At least they did that’ my father said.

◊

The following poem is dedicated to the Levenbergs of Libau, my great aunts and uncles and their children who were murdered in Libau in 1941, the Riga ghetto and my grandfather David Loewenberg/ Levenbergs.

◊

- A Place Near the Sea

- ◊

- As they hurried in line

- As the cameras clicked

- As they removed their clothes

- As the children cried

- As they whispered goodbyes with their backs to the ditch.

- ◊

- One can only hope.

- One can only hope.

- One can only hope that the wind softly sighed

- And sea spray kissed their hair.

- Die Gedanken sind frei.

- ◊

- Thoughts are free.

Photo of women being killed at The Šķēde dunes by Germans and the 21st Latvian Police Battalion. The massacres took place from December 15 to 17, 1941. Forced to line up in groups of 10 and with their backs to the ditch, (which Latvian police had dug during the preceding weeks), victims were then made to face the sea as a squad of 20 men fired at them from the other side. For further photos see: http://www.liepajajews.org/ shkede_web/index.html

◊

[1] When World War II started in September 1939 with the German invasion of Poland, Latvia had come under the Soviet sphere of influence in the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and its Secret Additional Protocol of August 1939. The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, was an extension of the Munich Pact (‘betrayal’ as the Czechs had named it) that Germany, France, Italy, and United Kingdom had signed on 30 September 1938 to determine the areas of influence in the East after Czechoslovakia had been divided between Germany, Poland and Hungary.

[2] For further details see Inge Lammel Das Juedische Waisenhaus in Pankow. Seine Geschichte in Bildern und Dokumenten (2012) Berlin, Hrsg vom Verein der Foerderer und Freunde des ehemaligen Juedischen Waisenhauses in Pankow e.V und der Vereiningung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes-Bund der Antifaschistinnen und Antifaschisten VVN-BdA Berlin-Pankow e.V.

◊

Acknowledgments

The article originally appeared in the May 2017 issue of Second Generation Voices published by the Second Generation Network in the United Kingdom. My sincere thanks to Dr. Aleksandrs Feigmanis of http://www.balticgen.com for providing us with photos of the Jewish community in Liepaja. Further images can be found on the following Bundesarchiv link. Search Liepaja 1941 at: http://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/cross-search/search/147897240/?search[page1=2.