MEMORIALS FOR JEWISH COMMUNITIES | MOLĖTAI (MALAT) | MUSEUMS

◊

by Viktorija Kazlienė

◊

Almost five years ago, an exceptional March of Jewish Remembrance took place in Molėtai, on 29 August 2016. On that occasion, an impressive monument was erected at the site of the mass murder of the Jewish citizens of Molėtai (known in Yiddish as Malát). For that, we are grateful to Tzvi Kritzer, a descendant of Molėtai Jews now living in Israel. Leonas Kaplanas, another son of survivors from the town, now living in Vilnius, also contributed significantly to organizing the March.

◊

◊

News about this march of reconciliation spread across the whole wide world. Lithuania’s famed playwright, National Prize winner Marius Ivaškevičius, born and raised in Molėtai, took up the role of the most wonderful influencer promoting the march. Seventy-five years after the events, for the first time, Lithuanians walked the road of Jewish suffering and death alongside Jews themselves, to honor the Holocaust victims and to try and apologize for the crimes committed during the Second World War.

Every year, on August 29, famous Lithuanian playwright Marius Ivaškevičius takes part in the events of the Remembrance Day of the Molėtai Jews. Photo: Alvydas Balanda

On the day of the march, a single large tombstone, a memorial to mark the site of the Molėtai Jews’ genocide, created by famous Lithuanian-Israeli sculptor Dovydas Zundelovičius (David Zundelovitch), was unveiled. The sculptor worked pro bono, the costs were those of the monument’s materials, transport, and erection.

The miltilingual monument created by Dovydas Zundelevich was unveiled at the August 2016 march. Photo: Alvydas Balanda

Exactly a year after the March, a documentary on the Holocaust in Molėtai, The Last Sunday in August, financed and produced by the same Tzvi Kritzer, was premiered in Tel Aviv and later shown in Vilnius and a number of cities around the world.

◊

This year marks the eightieth anniversary of the Holocaust in Lithuania. There are six additional sites of Holocaust atrocities in our Molėtai District, recorded in the registry of the Department of Cultural Heritage (DCH). They too deserve proper attention. This task requires resources, ideas, a lot of negotiation, and a lot of intelligent and sensitive work. The most exciting fact is that private persons are now also showing their attention to these sites and willing to offer material support for them to become sites of remembrance, truth, and reconciliation.

◊

Joniškis (Yiddish: Yánishok or Yáneshik)

The project to properly commemorate the burial sites of Jews of Joniškis was initiated by Vilnius businessman Vilius Navickas, who has a summer home near Joniškis. He got together on this project with his friends, the artist Saulius Paukštis, famous for his monument to the American rock legend Frank Zappa in Vilnius, and sculptor Šarūnas Arbačiauskas. There are two burial sites of the murdered Jews in Joniškis: one for the men and one for the women, who were murdered separately.

Both sites are in picturesque locations, on the shores of Lake Arinas.

To this day, there is a living story that one of the men escaped. This is in line with Efroyim Vainpres’ testimony in L. Kaniuchowski’s book. However, it was rumored that the man jumped into the lake at night and rushed to swim to a small island nearby. He was shot in the water, but it was still thought that he had sailed somewhere, both literally and figuratively.

Seventy Jewish men were murdered and buried here during a mass killing organized by Nazi German authorities and carried out by white-armbander batallions of Joniškis and Raša Manor. Some private individuals are planning a memorial that will memorialize each murdered person.

◊

Eighty-five Jewish women and children from Joniškis were murdered and buried here during a mass killing organized by Nazi German authorities. Here, too, there are plans underway to build a memorial that will symbolically commemorate each murdered person.

◊

A model of the monument by sculptor Šarūnas Arbačiauskas to the memory of the Jewish community of Joniškis destroyed during the Holocaust

◊

To properly and meaningfully commemorate our region’s problematic history is a truly complicated task. For that, one has to have knowledge and sensitivity and find a proper expression of the quest for truth: to get acquainted with and explore the situation, to search for remaining information, to apply a critical view, to find a relation with vibrant Jewish culture, to work the idea indo a doable project that can move good causes forward.

It is the view of Dovid Katz, the specialist on Lithuanian Jewish culture, there always needs to be a proper memorial in the town center in addition to those at mass graves in the forest. He believes the town center memorial needs to contain basic information including the numerical and cultural magnitude of the erstwhile Jewish population, as well as a summary of their fate. He mentions that he learned this from the last Jew of Amdur (Indura, near Grodno, in Belarus), Eli Goldfand, who imparted this wish on his deathbed, about the future memorialization of the Jewish people of his own town.

In 2020, an English translation of testimonies of the Holocaust in Lithuanian towns compiled by Leyb Konichowsky was published. Among the 121 testimonies is the one, on p. 237, about the massacre in Joniškis (Yiddish: Yánishok or Yáneshik). Fourteen-year-old Efroyim Vainpres, who escaped the site of the massacre, or, to be more exact, the grave pit that he had dug for himself and those selected to meet the same fate, told the world, and us, on how everything happened in reality.

◊

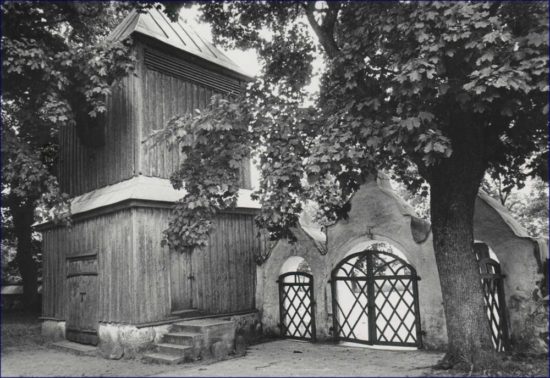

Inturkė (Yiddish: Inturik or Antúrke)

In the Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland and other Slavic Countries, published in Warsaw between 1880 and 1902, there is a short but informative excerpt on Inturkė. There is a lot of information on Lithuania in this dictionary, although Lithuania is not deemed to be a “Slavic country”. We find here that Inturkė is a town in Vilna Province on the shore of Lake Gieliotas (Golionas). We find its geographical location, as well as the presence of a Russian Orthodox Church here and the Catholic Church of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, founded by Queen Bona Sforza d’Aragona in 1555. Inturkė had 119 inhabitants. The Orthodox parish had 563 members, and the Catholic one — 3,382. It was a parish of the last, fifth class, it belonged to Giedraičiai Deanery and had a chapel in Rudesa. Inturkė had formerly been an eldership (as an administrative unit), but at the time of writing belonged to both churches and peasants. The village (non-urban) eldership of Inturkė had been governed by the Province of Vilna authorities. According to the property census, Inturkė and the surrounding villages had been permanent royal property since 1569. From 1766, Inturkė belonged to Towiansky, the Vilna Horoder (governor of provincial lands), with a quarter of Poland’s Hibernian (Irish) taxes paid by him. Later, the eldership was transferred to the Kontrymas family for fifty years, at which time, in 1866, Inturkė had 14 dūmas [households of manor-less nobles], 414 inhabitants, a manor, and 31 inhabitants in the inn.

A historical record on Inturkė cited on Jewishgen states: “Until 1923 the rabbi was Zalman-Tuvia Markowitz. After he left for Anteliepte (Antalept), no new rabbi was appointed; and regarding all matters of religion the Jewish community of Inturke was served by Rabbi Beilitsky of Moletai.”

Berl Kagan’s famous Yiddish Encyclopedia of Lithuanian Jewish Communities says, of Inturkė: “Starting from 1898, records of the town rabbi Yéysef-Kháyem [Joseph Chaim] Trop, born in 1872, are found; later he would become rabbi of Višintė. Another town rabbi was Reb Shléyme-Zalmen [Shlomo Zalman] Markowitz, born in 1887, previously rabbi of Kovarsk, rabbi of Inturkė until 1925, and then rabbi of Antalieptė, murdered in Kaunas.”

◊

Mysteries of the Parašė Forest

Another benevolent businessman, Česlavas Kovaliūnas, born in Joniškis but now living in Vilnius, has offered his support for commemorating the Holocaust sites of the Inturkė Jews. However, the Inturkė Jews were murdered far away from Inturkė, in the Švenčionys (Svintsyán) District, Labanoras Eldership, in a remote forest by the village of Parašė (source). This forest hides many a mystery. Three separate murder sites of the Inturkė Jews are known and included in the registry of the DCH. However, on page 174 of the book Protecting Our Litvak Heritage: A History of 50 Jewish Communities in Lithuania, published in 2009, it is stated that “The first week, following upon the German offensive, sixty Jewish youngsters were shot and buried in the swamps of Babulka, 500 meters behind the old palace.”

I became interested in finding these “swamps of Babulka.” Žanas Malčanovas, Head of the Lakaja Forest District in the Švenčionėliai (Yiddish: Svintsyánke) Forestry Enterprise, helped me find it. He took up the effort to go see the locals and ask them about it. Some people said that the swamps of Babulka are not far from the Raša Manor, next to which are the three burial sites of the Inturkė Jews. However, later, when trying to find out, which of the three burial sites is the closest to the swamps of Babulka, the story became even more convoluted. Witness Ona Leleivaitė Radzevičienė, born in 1931, confirmed that people would indeed refer to a certain place in the forest in those terms. She came to live there in 1950, after getting married. The real witness was her husband Rimgaudas, who is now deceased. Then it appeared that there is another person who could help us, grandson of Ms. Radzevičienė, Mr. Linas Vyšniauskas, now 41 years old, who remembers his grandfather telling him that there is another burial site, exactly at the swamps of Babulka, but that it was never marked nor commemorated, because when public interest finally came to include commemorating Jewish murder sites, it was allegedly impossible to point to its exact location. Everything was overgrown with scrub. Back then, his grandfather could not show where it was exactly, and the site remained unmarked.

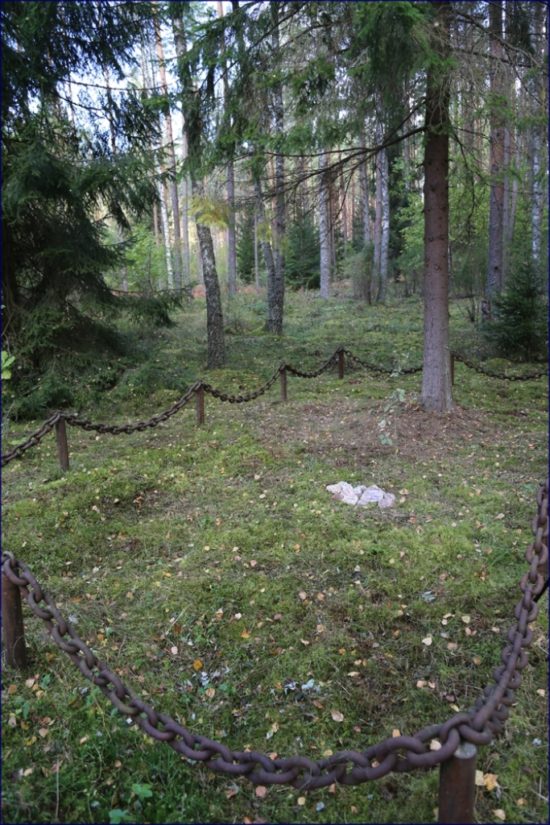

Mass grave site in the forest where Česlavas Kovaliūnas plans to build a monument to the Jews of Inturkė buried here

This way, a major event of the week of 22 June 1941 was brought into the daylight. Later it became clear that it was not only Jews from Inturkė that were murdered there. The owner of the Raša Manor, Algirdas Petronis (the son of Petras) was the one who carried out this mass murder. All these sites of murder and mass burial are in the former lands of the Raša Manor. Nowadays it is a state forest in the Lakaja Forest District of the Švenčionėliai Forestry Enterprise.

On page 411 of Mass Murder in Lithuania, we read: “Jews of Molėtai County were murdered in Ruoša farmstead, in the so-called Babulka meadow-swamp, 500 meters from the former manor.” Sadly, nobody ever had the idea to find out where precisely this Babulka meadow-swamp was, whether this location is adequately marked and taken care of, whether there is a plaque commemorating this event.

◊

“Janner’s Columns”

Since the year 2000, special markers have been erected to point the way to the sites of mass murder. Each is a short stele (column with its top severed diagonally) of polished black marble with the Star of David and the distance to the site of mass murder and burial on them. These were financed and built in Lithuania by former Chief Executive of the UK’s Holocaust Educational Trust, Greville Janner (Lord Janner, 1928–2015). There are more than 200 of these monuments that are known as Janner’s Columns. For some reason, one such Column in the Parašė Forest displays misleading information. It should be moved to another place to show the indicated distance to the site. And in Joniškis, Janner’s Columns are built right next to the massacre sites, defeating their function of showing the way from a nearby main road.

One of the “Janner Columns” pointing to the mass grave with an indication of the distance. In Parašė Forest

◊

What should be written on the monument for the Jews of Inturkė? The first idea that crossed my mind was that a web link to the names of the murdered Inturkė Jews on the website of Yad Vashem, itself the most beautiful monument in the world to the victims of the Holocaust, located on the Mount of Remembrance in Jerusalem. These are the names of more than four million, eight hundred thousand Jews, out of the six million murdered by the Nazis and their collaborators. The public is invited to supplement these lists with names of victims not yet included.

At the 2016 Molėtai March of Jewish Remembrance, descendants of the Inturkė Jews took part. They included the world-famous mathematician Prof. Mina Teicher and her brother Koby Sheftel. They wanted to pay respect to the murdered Inturkė Jews, but, in Inturkė itself, they found no information on where these burial sites were or how to find them. While looking for inspiration for the idea of the monument, businessman Česlavas Kovaliūnas and I contacted these people to inform them on this initiative and ask for their views and suggestions.

An author’s idea is always welcome, but people cannot help but think of the number of the innocent victims and compare a human’s life with a candlelight. And the exact number is still unclear.

According to the International Jewish Cemeetery Project, “Prior to World War I, 62 Jewish families (250 persons) lived in the village, but before the Holocaust only 40 families remained including the adjoining village, Raitarada. Others emigrated to South Africa, the USA, and a few to Palestine. In 1919 a great fire in the village destroyed almost all the Jewish homes. The population was reduced further during the period of independent Lithuania when Vilnius was ceded to Poland. The Jews worked as fishermen and petty merchants. Three annual market fairs took place annually. A bes-médresh (study and prayer house) and, before World War I, a small yeshiva existed. During Lithuanian independence, a small public library, but no school or khéyder existed, so children of Inturke attended schools at Moletai, Kaunas, and Ukmerge (Vilkomir). On the eastern side of one of the lakes about one kilometer away, was the village of Raitarada with a Jewish community of twenty families. A post office was opened in 1926.”

The book Jewish Communities in Lithuania states that 23 Jewish families lived in the town in 1939, but it could be that those from neighboring Raitarada were not included here.

Forty families could be comprised of 200 persons (families used to be bigger at the time), but there are three burial sites. Today we can only speculate, why and how the murderers divided the condemned into these three groups. One witness said that someone tried to “check” one of the burial sites, and left it somewhat uncovered, and reported seeing a child’s shoes at the site.

At present, only the first site included in the DCH registry has a metal plaque, fenced off by iron chains, on which it is written, in Hebrew and in Lithuanian: “For the commemoration of the Jews of Inturkė, killed by Hitler’s executioners and their local collaborators.” The other two sites remain bare, graves fenced off by thick iron chains, with no commemorative signs of any kind.

As stated by the witness in Leyb Koniuchowsky’s The Lithuanian Slaughter of Its Jews, the massacre in Joniškis was carried out on July 8, 1941. But the DCH online registry presents this version: “On July 24, 1941, 70 male Jews from Joniškis were murdered and buried during an execution organized by Nazi German authorities and executed by white-armbanded batalions of Joniškis and the Raša Manor.”

It is probable that the Inturkė Jews were murdered in July, too.

There is moreover testimony in Koniuchowsky’s book that “[…] seven men had been taken away had been shot that same Monday evening in the forest of Armenu [Arnėnų], at a polygon, about six kilometers from Joniškis in the direction of Podbrodz [Pabradė].” Now a military training ground occupies the site, already beyond the border of the Švenčionys District, the territory is fenced off, and the site is not included into the DCH registry. We should perhaps consider including the names of these seven men (they are all known) in the monument at the Joniškis Jews’ burial site memorial.

A suitable inscription on the monument for the Inturkė Jews could be:

“We remember you, forty families of Jews of Inturkė, who were murdered here in cold blood by local white armbanders in 1941 and buried in the graves numbered I, II, and III.” Each grave could be numbered, just like in the DCH registry. The text should be in Lithuanian, Yiddish, Hebrew, and English.

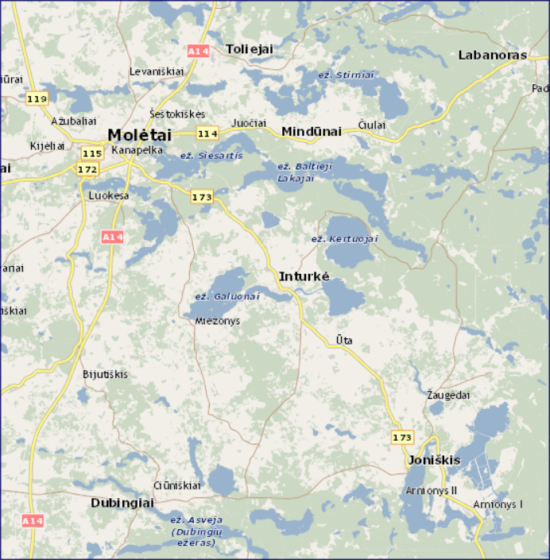

The region covered in the article. For reference: Moletai (Malát) is located around 60 km (37 miles) northwest of Vilnius.

Viktorija Kazlienė is the director of the Moletai Regional Museum.

◊