◊

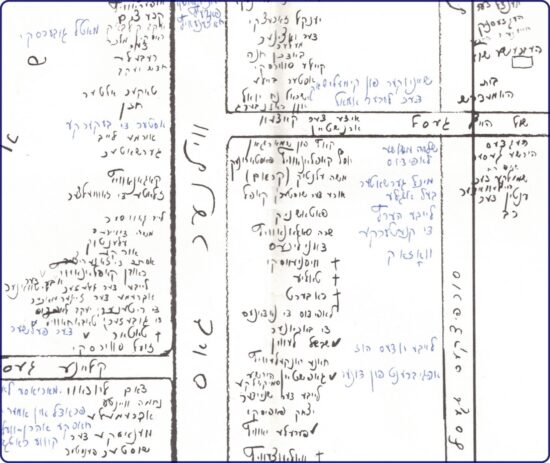

Names of Mikháleshik

Dveyrke I, Dveyrke II, Dveyrke III

At a Patched Window

On Your Name

On Hunting

A Shade Or Two

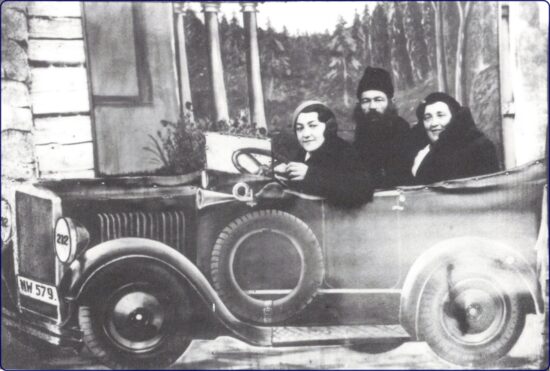

Eltshik and Dveyrke

Gold Diggers

Cry Wizards

Before Battle

Two Armies

After Battle

Children of Pig Street

On God’s Children

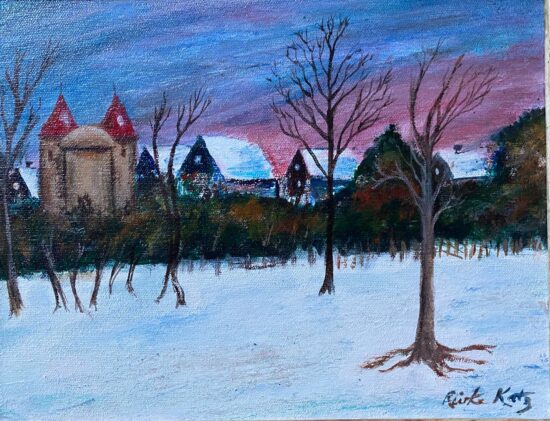

Snowfall in the Village of Mikháleshik

Neverland

Sundown on the Old Street

In the Year of Three Thousand and One

Return to the Village of Mikháleshik

Deserted Winter House

Visit to the Village of Mikháleshik

Dancer

Old New York Sundown

Race of Ghouls

◊

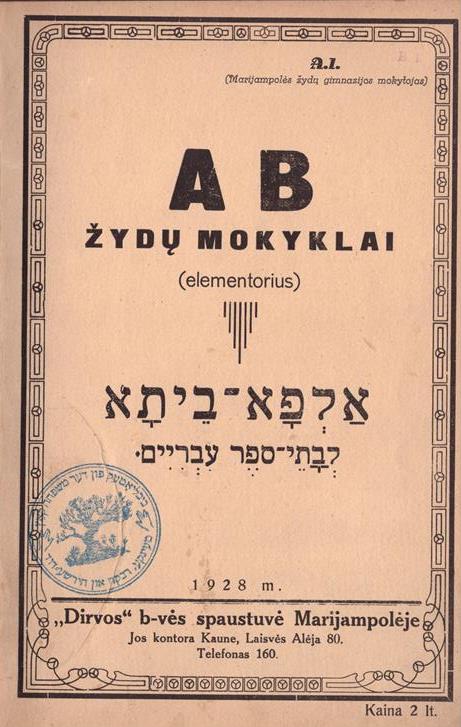

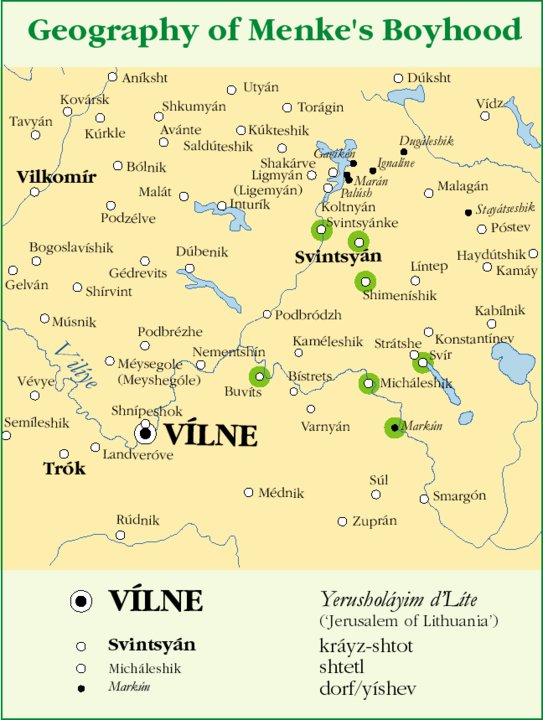

Part of the Mikháleshik Yizkor Book project. See also: Menke’s Yiddish poems on Mokháleshik translated into English by Benjamin and Berbara Harshav.

See also: Menke Katz resource page

Menke’s books, essays, autobiography, biography, 9 Yiddish books, 9 English books

◊

Names of Mikháleshik

- Mine are the names outmoded as the kindness of my mother,

- humble as the cool shadows in the evening woodland,

- where echoes do not pine away for the love of Narcissus,

- but in yearning for a yell of the vanished children of Mikháleshik.

- The restless rivulet roving through hankering Pigstreet,

- will repeat forever and a day the names of Mikháleshik.

- Listen:

Yeiske – Meishke – Blumke – Menke – Berke – Eltshik. - ◊

- Yeiske, real as this rhymeless prayer to love:

a thrilling chill from the snows of my childhood,

entrancing as Joseph through the dreams of Pharaoh,

not in dungeons of Egypt but on mudlands of Lithuania

cherished by a wish of a homeless, hunted Jew.

Yeiske, genuine as the light of my eyes. - ◊

- Meishke, a name moving as an oar of a home-made rowboat,

- rowed idly by a lone, love-wounded lad.

- longing for his barefoot maiden over the Viliya river,

- which hugged the townlet of my bearded forefathers:

- rich in mighty dreams, proud with hoary wisdom.

- The crude oar in lover’s hands, miraculous as Moses’ wonder rod.

- ◊

- Blumke, brisk as stray seeds flung into your face by a slapping wind.

Her hair braided with tough flowers growing out of the stones of a ruin.

Her fingers sore from plucking sorrel out of thornbushes.

Winter, she mellows by the light of cherubs on wings of icicles.

The sudden gust through frost-weeds rustled her in silks.

Blumke, sister of dandelions — O tear kissed sister of mine! - ◊

- Menke, laughworthy, not worth the eyehole of a needle, —

but my eyebrows are opulent, bushy as thoughts of life after death:

My father’ss eyebrows — the pride of the baretoed nights of Mikháleshik,

eager as expectant moments of a long-awaited beloved. - My walk is light and free as my mother’s laughter.

- I am dangerous as at twilight a falling day,

- daring as a newborn word, startling as a freshly molded verse.

- I am chatty as Yiddish, my mother tongue.

- I dallied with dreams as in a game of jackstones,

- when stars paved the crooked, unpaved alley where I was born.

- ◊

- Midnight.

- The candlelit house struggles with the night, blind as a mole.

Berke — a boy left all alone in the depths of a “kheyder” tale,

where a dark forest glares only with the eyes of a threatening bear.

The bear is shaken by the awe of the pleading boy:

“O, bear, bear, bearele, be timid and kind,

mamma will surely bring you tomorrow

a tasty cooky flavored with poppy-seeds.” - ◊

- Eltshik is the neighboring brother from the nearby cemetery:

a lad wrought on a windowpane of our age-weary house,

caressed by pitiless winter, pampered by bleak, freezing design.

Eltshik — a name scorched under the ashes of fire fiends.

Mikháleshik in flames toward a deaf, godless sky,

carries him to heaven, like Elijah, on horses of fire. - ◊

- The moon is a snow-apple of a delusive orchard,

- to tease hungry little brothers and a fright-skinned sister.

- Carved in traceries of frost-work appears Elijah of Gilead,

- seeking death, in vain, under a broom-bush,

- with God not in wind or fire, but in tender whisper.

- The smell of caves of the wilderness on his clothes.

- The kindness of a far lucky morrow in his eyes.

- Real and near as the next-door neighbor,

- he opens for the children a bagful of bread,

- brought to him by ravens at the brook Kerith.

- Eltshik is the light of his long shining beard.

- He scatters on the windowpane the three hundred bits of silver

- which Joseph gave to Benjamin in the land of Egypt.

- The cheery sister picks frost-beads for a fairy garland.

- The wealthy little brothers gather the fancied coins.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), pp 32-33. First published in Commentary (Feb. 1959).

◊

Dveyrke – I

- The dingy street — Zohar-lit, a wonderland.

Folks sing of the rarest gems found in tears.

Paupers give alms with Elijah’s blessing hands.

Splendor crowds the lurid lanes when you appear. - ◊

- Your steps in sandals are as Shulamite’s,

though you keep not the vineyards of En-gedi,

but the simple brooks — the wandering myths

of Lithuania. Your breath of En-gedi. - ◊

Kabbalists turn dust into flesh, bone into rays.

The moon frays the silver off its face with mud,

dreams and soot of the wistful alleyway.

Tales of princes bring a castle into each hut. - ◊

- Legends slumber in crumbs of light, in stones and thorns.

- Nearby‚ swim starry maidens, river-borne.

◊

Dveyrke – II

- The trance of sephiroth in the dying day. Mean

- winds bang the loose shutters of the old house.

- We vow to love ever-craving as the stream.

- Fresh from the stream the knit daisies of your blouse.

- ◊

- Dveyrke, coy, dimpled maiden of my childhood,

- with the yearning of my hometown in your eyes:

- comely as Mikháleshik, where my cradle stood,

- where beards are thick with pilpul and thumbs are wise.

- ◊

- My words to you untouched as kisses in a dream.

- Yours — the treasure-hunt by an unknown poet owned:

- a weeping flute playing for the stone-eared lost hymns.

- Mine — what is left of you: gold of days, never dawned.

- ◊

- Forlorn I stand — a cursed tree which gives no shade.

- Harvests yield the fragrance of your hay-scented braids.

◊

Dveyrke – III

- “Our day dream is a lone oasis through the crowds of New York.

- Tender as the light of unborn days you come with aurora.

- You walk through a golden Mikháleshik on streets of New York.

- O Dveyrke, your name: raw, strength of Yiddish, love of Deborah.

- ◊

- “The streets welcome you with carefree laughter of sparkling children.

- Nodding snowdrops in a schoolyard promise you the nearby Spring.”

- “I come from Oschwentchim, a strangled child of God’s chosen children.

- I know, white flowers are sisters of snow, the first tears of Spring.

- ◊

- My heart is a black orchid, spun of ashes, my touch might

- turn every stone into a tombstone, my dimples into scars.

- The first rays are shamed, untouched wine-cups for our marrying night,

- as I leave beyond dawn, dreaming of you in a bed of stars.”

- ◊

- I see Mikháleshik in heaven — the prettiest alley.

- O bride of my daydreams, O Zion’s lily of the valley.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), pp. 34-35.

◊

At a Patched Window

- I am a lover, a pauper, and a poet.

- My heart is clean beneath the threadbare shirt.

- I learned wisdom from the Talmudic skies of Lithuania.

- I am gracefully uncouth.

- I cleaved my grace from the slums of New York.

- ◊

- My father like Columbus dreamed of America, when I was born.

- My childhood wanned at a patched window,

- where I imagined a cake soaring like a cherub,

- where I saw candy, toys, and cocoa,

- under the wings of a nymph only.

- ◊

- The cruel hand of destiny led us through hunger, war and plague.

- We were four little brothers and a scrawny sister.

- In the autumn garret we heard the song of Spring,

- as crawling doves would hear the giggle of their craven victor.

- The wind through redolent meadows was a bleak laughter.

- ◊

- O our weary mother carried us

- through the prosperous thorns of our scared little town, Mikháleshik,

- From a fairy tale came the night — a spectral undertaker,

- to bury the thorny day of Lithuania.

- God was the baker from Eden who baked the tasty stars.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), p. 36.

◊

On Your Name

- O your name may be

- tender as the sore wing of

- a baby eagle;

- soothing — mother’s first refrain:

- — ai – le – loo – le, loo – le – loo.

- ◊

- Your name may be harsh

- as Yiddish — proud mother tongue

- of witch-hunted Jews;

- when words hit with the wrath of

- stones flinging against a foe.

- ◊

- Your name may be bleak,

as the house where you were born,

where I saw your first

light-hating dawn streaking gaunt

specters on the cold chimney. - ◊

- The walls — mossed humps, (were

once gallant birch trees.) gilded

by the gloom of a

timorous wick. I saw you

a newborn apparition. - ◊

- Our mother — tallow-

pale, fancy-stung. The rocking

cradle conjured the

shades of the haunted ruin:

the adjacent land of fiends. - ◊

- O Mikháleshik,

- our village in Paradise

- dreams of herring and

- potatoes. Our reveries

- twine through the twisted alleys.

- ◊

- The trees of Eden

- grow on frost fettered casements,

- crave in vain the ax.

- Your name — five frozen claws in

- assault: Y! E! I! SSS! KE!

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), p. 38.

◊

On Hunting

- I heard the legends

- of Mikháleshik at a

- brook in New England.

- I saw the deer take your moods

- in a dash to the unknown.

- ◊

- O leave for the armed

- coward the skill to

- vie with a trapped deer;

- the fun to pierce the heavens

- with the cry of a shot bird.

- ◊

- In the plundered nest

- only ghosts hatch their cursed eggs.

- Calm has a vile tongue.

- Even stumps are wounds in the

- twilight woods. Even stones bleed.

- ◊

- The cat bird — a pest

- mews odes to a craven ghoul.

- The wind strews baned seeds.

- O hear a dead bird with a

- broken beak peck someone’s skull!

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), p. 40.

◊

A Shade Or Two

- We will die singing

- Yiddish, heartrending folksongs:

- hoary lovers with

- the idle, witted delight

- of our kind-jawed grandfathers.

- ◊

- Let us say there is

- a Mikháleshik beneath

- its ashes, beyond

- our dust and we will play love

- on the coiled lanes with elf maids.

- ◊

- Let us say there is

- no end. The end is just an

- instant earlier

- than beginning. Darkness is

- just a world older than light.

- ◊

- Just a wound between

- thorn and violet, just a

- flare between frolic

- and gloom. Only a lightning

- between silence and thunder.

- ◊

- O let us say there

- is a bygone heaven not

- a bygone love. Death

- is simply a shade or two

- other than life. No sunset

- ◊

- grieves to its last ray.

- We are in the afterglow:

- far, scintillating

- beacons — hermits of the sky.

- O ever circling, stray moons!

- ◊

- Years surge and recede:

- a sea driven to the shoals.

- We yearn through wind, dust.

- Longing is a hurtful grace,

- not within the grave to hide.

- ◊

- My hymn to you will

- never end. At each moondown

- will ever meet in

- mystic Safad two brothers,

- two poets of long ago.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Land of Manna (Windfall Press, Chicago 1965), pp. 42-43.

Eltshik and Dveyrke

- unrhymed unrefrained chant royal

- ◊

- ◊

- Eltshik, my brother, you died at seventeen.

- You will be ever and ever seventeen

- as on the wonder island of Bimini.

- No retreat is as good a haven to yearn

- for you as on the thronged streets of Manhattan,

- no solitude solemn as dusk on Times Square.

- Subways in the rush hour know my hymn to you

- when crowds flock as if to celebrate their

- next to live, the adventure of being born,

- shout down the city: Ho! Waiting in endless

- row of ages since Genesis, we arrived!

- ◊

- You saw your last sunset in Mikháleshik,

- our hometown devoured by retreating armies,

- limping to their death on Lithuanian

- bareboned earth. You died longing for your maiden

- Dveyrke bound by an oath at the open ark

- of the moonlit synagogue that your love will

- live as long as Spring, flowers and bees will meet.

- Moses walked out of the Torah to witness.

- The creek rolled like the pilpul of the Talmud,

- drowned in dispute of the wise sages who live

- in the mirror of the river Hiddekel.

- ◊

- O good to find our lost hometown in New York.

- Shadows of buildings give shade to the same sky,

- prankish cherubs play hooky on towerpanes.

- A tower ascends like our town in a dream,

- the hovels climb over one another,

- reaching for the known unknown to remind God

- it is time for Messiah to rouse the dead,

- to wake the children massacred at their play

- while kneading out of mud-pies a new Adam,

- to resurrect the tattle of the mute hag,

- every blot and blemish — the true signs of life.

- ◊

- Charon on a cloud ferries the dying day

- through the dark memories of the river Styx,

- a day smoke-eaten as an ashen alley

- of my childhood against the howls of battle:

- June was foul with the rootrot of red armies,

- uterine brothers of plague breeding storm troops,

- proclaimed free gallows for all creeds and races.

- Poor Satan was a farmer with a gory

- sickle, beheading Jews, God, Tartars alike.

- The sun was like the gold head of King Midas,

- the last rays pondered on spears, in love with death:

- ◊

- No kindness is as kind as comrade Death.

- Kind is a felled tree made into a coffin.

- True are flowers daunted in a mournful wreath.

- No beginning is as gracious as the end.

- Dveyrke appears, stars hold her silver bride chest.

- Left of her is her voice in sobbing rivers:

- — Come my love out of the lovers of evil.

- It is the end of grief, the end of Sheol.

- The charred gibbet can only frighten itself.

- The folks of hell break the sword guarding Eden!

- • • • •

- The city reborn, rides down the skyline drive.

- ◊

- Eltshik, there is more wonder on Fifth Avenue

- than in the hanging gardens of Babylon,

- there is more legend in our casual chat

- dallying with time at a cup of coffee

- than in Scheherezade’s thousand and one nights.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Rockrose (Smith Horizon Press, New York 1970), pp. 74-75.

◊

Gold Diggers

- Mikháleshik, village of my mighty

- ancestors, bearded rivermen reared in woods,

- with the chilled iron of axes in their glance,

- foil the foe gnawing the root in its crib,

- wean the saplings in their tree nurseries,

- towing barges, drive onward to Eden:

- Yiddish flowing as the Viliya river,

- biting as the coarse teeth of a ripsaw.

- Earthbred, illstarred gardeners with lucky spades,

- digging potatoes like buried treasures,

- gold diggers with potato forks ransack

- the furrows stabbed with daggers of broken rock;

- the potatoes — tricksters, play hide and coop,

- in the tired earth of Lithuania.

- ◊

- A flock of roaming goats frolic around

- the “ hekdesh ” where the beggars, the feeble,

- the chronic derelicts loiter, grazing

- the straw roofs blended with duff and leafmold,

- hit by the evil eye of goat suckers;

- the he-goats: whiskered, entranced goat-gods

- gallop at midnight, in illuminous

- ecstasy when terrorized by a falling

- meteor, a mortal from Paradise,

- a fugitive from the night sky, breaking

- away from the chains of infinity,

- bringing the twisted lanes into the

- solar ranks as if dilapidated

- Pig Street and the seventh heaven are one.

- ◊

- Eden on Fridays is always nearby.

- Angels visit here like next door neighbors,

- assert that Elijah is on the way,

- with the Sabbath feast for the Sabbathless poor.

- Badonna, mother of a craving fivesome,

- depends neither on angels nor Elijah,

- but on the miracle of her skilled hands

- which pick the wood-sorrel, the berry-cone,

- garlic, the pride of the lily family;

- lentils, the value of Esau’s birthright,

- sauce sweetened and stewed to a goody pulp,

- the keen aroma of cool ciderkin,

- made of the tasty refuse of apples,

- of rootstock, the seed, stem and skin of the grape.

- ◊

- If not challahs fit for a silver wedding,

- a roll, by the grace of blessed candlelight,

- with a scent of honey for the Sabbath queen.

- If not gefilte fish stuffed with savored crust,

- a herring, humble as fresh waters, spawning

- in sod huts, legends of the North Atlantic.

- Mead, (call it wine with a raw grain of salt)

- served in laurel pink goblets from pitchers

- bom by the hands of village potters, with

- ears and lips of clay licking yeast, honey malt,

- adorned through ghost-fire in underglazed colors,

- stored in dark cellars to drink lechaim

- to each breath of every creature on earth,

- at the light of the long zero winter.

- ◊

- Children in the rapture of reveries

- see their father Heershe-Dovid in far

- America, mining the gold of the silks

- fondled in the factories of New Jersey:

- The “hekdesh” turns into a castle of gold.

- Eltshik leads the human wreckage into

- a world baked like a round kugel, the moon

- of yogurt, the stars — crisp potato balls.

- Berke rides a bear made of prime confetti.

- Menke sees Jonah in the kind whale, welcomed

- with milk and honey. Yeiske is about

- to reach the sun as a plum of bonbon.

- Bloomke, the only sister, cries over

- spilled milk of crushed almonds, to nurse her

- pampered doll made of the sweets of marzipan.

- O the dream is swifter than the wind, it brought

- America into Mikháleshik.

- ◊

- Heaven on earth is in the children’s eyes.

- Who is richer in gold, America

- or the sun? Eltshik says: at dawn, the sun

- is richer, at twilight, America.

- Berke tells of a street — a dream in New York,

- paved with silver dollars like little moons.

- Menke in “kheyder” confides, his father

- Heershe-Dovid (tall, yearning and handsome)

- sailed the seas to change his jaded horse

- for a gallant filly, the squeaking wagon,

- for a two-wheeled pleasure carriage; to trade

- the cow with the drying udders, hardly

- enough for milksnakes, — for a herd of an

- aristocratic breed with teats like milkwells.

- Sunset. Yeiske sees the clouds sail like boats

- with gold which dad sent from America.

- Bloomke fears there may be a shipwreck in

- the clouds and flood the village with gold.

- ◊

- O the singing Jews of Mikháleshik:

- O my unsung uncles, gloried horseshoers,

- famed to shoe horses as they leap off the ground.

- Jews with bodies like wrought metal; hammers

- pride their hands over the anvils; felling

- trees, hewing timber: robust, manful lovers,

- lure the longing mermaids out of their streams,

- to break their mirrors into dazzling charms,

- to languish lovemad at their feet, to pine away,

- on the mudlands of the Viliya river.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), pp. 12-14.

◊

Cry Wizards

- April.

- All fools’ month.

- The palms fool the

- palmreaders, the stars

- fool the stargazers. The

- village of Mikháleshik

- echoes with the weeping of the

- professional mourners, the elite

- of the hekdesh, the beggar’s guesthouse, the

- womenfolk with eyes like unloaded tear bombs,

- cry wizards who gathered to fight the oncoming

- German armor with lament, bewailing yesterdays

- todays and tomorrows dead, form a wailing chorus with

- the homeless, the barefoot wanderers of Lithuania.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), p. 24.

◊

Before Battle

- Listen to the silence, in the village

- of Mikháleshik, a sudden voice is

- like the crack of a whip. The ferry barge

- rocks idly, yearns for its barefoot captain.

- ◊

- The houses huddle behind their shutters,

- devour their sleep as a last meal. The night

- is sawed into pieces by the crickets:

- the fairy carpenters of the village.

- ◊

- Maidens hide in desolate attics, wreck

- with their frightful steps the skilled labor of

- industrious spiders who spun here through

- dark ages their silk treasures undisturbed.

- ◊

- All around the muttering waters of

- the Viliya river peel the bark of

- the hewn trees; beyond, wild forests breed wolves,

- local myths, haunted caves where robbers live.

- ◊

- Long winged petrels fly out of the burrows

- of rocks to presage the approaching storms.

- Jews at their midnight prayers hear the wind

- saying kaddish through the autumn willows.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), p. 29.

◊

Two Armies

(Tanka)

◊

- Two armies — two foes,

- two iron generals in

- their panoplies of

- fierce splendor, in their evil

- magnificence, from soul to

- ◊

- sole made of medals:

- the seals of death, outdazzle

- each other across

- the cascades of the two banks

- of the river, dauntless as

- ◊

- their machine guns, two

- gloried desperados of

- kaiser, sword and czar.

- Under their heels surge small fry

- sergeants, mace bearers, cringing

- ◊

- hoards; gunbright soldiers,

- wise as their guns, beam with right

- and left shoulder arms,

- with rifle salute, super

- shockmen learn the miracles

- ◊

- of the gospels to

- stride the waters like Jesus,

- the prince of peace, drill

- in reconnaissance, race to

- thwart counter reconnaissance.

- ◊

- Snipers — camouflaged

- dreadnaughts, concealed in ridges

- hide in the hellmouths

- of stone devils, under the

- brute eaves of cliffs, prying through

- ◊

- snoopscopes into each

- others sly schemes. A stray light,

- weary as if it

- traveled centuries, reveals

- treasures buried in legends.

- ◊

- Dew on bloodweeds are

- Job’s tears, gems of misfortune.

- A rosary of

- a dead soldier’s fingers points

- to a gaping sky as if

- ◊

- it were guilty of

- his death. A cliff resembles

- a blind Samson hewn

- of fog, cloudbursts, lightning storms.

- groping out of the ages.

- ◊

- Time shackled his mouth,

- stoned his scorn; rooted in rock

- he is from head to

- toes a tightlipped, clenched prayer,

- to regain his ancient might.

- ◊

- to down from pillar

- to post both horrormongers,

- the valiant doomsmen.

- winners of human carcass,

- the purebred lovers of hate.

- ◊

- Both foes, impatient

- as fire for the command to

- draw the triggers, to

- rush death out, to turn into

- dung every likeness of God.

- ◊

- Both intermingle

- their shout songs: rah! -rah! Hurrah!

- hurray! huzzah! yell

- themselves hoarse for each other’s

- throat. It seems barking barters

- ◊

- are here to compete

- for their hellware. death is their

- only buyer. The

- riverway which transports the

- timber of the wild forests

- ◊

- is a mirror of

- cold steel: spears, foils, bayonets,

- gleam in the hands of

- terrorful cossacks bred on

- the wrath of the fist, lulled by

- ◊

- the lullabies of

- rattling musketry, suckled

- from their mother’s breast

- lust for fire, swinging sabers,

- whips, scimitars; saw their panes

- ◊

- clawed with frostwork of

- bleak Siberia, winged with

- Caspian sea fiends;

- taught by the sword and buckler

- only the game of playing

- ◊

- havoc, of riding

- bare horseback on the kill, quick

- to reach the skull, the

- true emblem of conquest, the

- ghastly flag of victory.

- ◊

- Both armies pledge: not

- a mouth of the enemy

- will be left here with

- enough breath to tell of the

- grand holocaust. The Germans

- ◊

- howl: yah! the earth will

- whoop and holler with cossacks

- buried alive, the

- Russians swear: we will build of

- German heads a triumph arch!

- ◊

- Both armies — both foes

- bear the same witness: death, both

- are about to swarm

- to doom to ash the comely

- village of Mikháleshik.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), pp. 30-33.

◊

After Battle

- O the vicious calm!

- Even the owl on the roof

- is afraid to hoot,

- listening to disaster:

- the steps of night intruders.

- ◊

- Calm is the language

- of stones on the only paved

- alley — the warpath

- of strangling armies through the

- village of Mikháleshik.

- ◊

- Calm is the slumber

- of unemployed plows, dreaming:

- they cut. lift, turn the

- soil, prepare the seedbeds in

- deserted shops of blacksmiths.

- ◊

- Calm as the Godful

- eyes of a lamb (a bleating

- bundle of fear) which

- plead for mercy under the

- dazzling knife of the killer.

- ◊

- Calm is the tongue of

- ghosts with long snouts and small tails

- (of the slaughtered swine)

- which haunt the forsaken barns,

- smell the yellow blotches of

- ◊

- barley-scold, gnaw the

- wheat and apple rot, leak the

- milky stools stained with

- the first milk of heifers, ride

- on the skins of ponies, on

- the yoke of oxen

- who left here their sterile might,

- their harnessed summers.

- Calm is the wounded Saint Paul,

- made by the saintmaker of

- ◊

- the village with a

- heart of wax, eyes of fireclay,

- a soul of melted

- honeycomb, crying to the

- cursed earth: O tomb of heaven!

- ◊

- Calm are the unmarked

- graves of soldiers which keep rank:

- loco and poke weeds,

- com cockle, the skunk cabbage

- of starved Lithuania.

- ◊

- Hooded crows attack

- the calm like carrion, crow

- the names of unknown

- soldiers, darken the twilight,

- prophesy the end of days.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), pp. 34-35.

◊

Children Of Pig Street

- Children with symptoms

- of early blight, yearning to

- break into bloom on

- the tearful alleys of the

- village of Mikháleshik,

- ◊

- bear on their faces

- the puddles of the village,

- the swamps of the low

- lands, troublesome as the fire

- weeds which thrive on the grief of

- ◊

- blackened fields, scorched by

- the fleeing foes before the

- wheat is bearded, run

- the stray dogs away from their

- catchers, the mice — from their traps;

- ◊

- climb trees to learn from

- the loud voices of tree-toads:

- (the weather prophets)

- to predict rain, shrill with the

- piping call of spring peepers.

- ◊

- Children — fugitives

- hide with deserters of maimed

- armies, in murky

- haymows, in the ruins of

- Pig Street, in bush and jungle.

- ◊

- Children — haunted by

- the sister goddesses of

- song and art, science

- and music, adorn even

- the outhouse with their fretwork.

- ◊

- They learn design from

- frostwork on windowpanes, carve

- hyenas with smiles

- of hangmen on every sash

- of the whitehearted jailer.

- ◊

- Butte, roof and mesa

- is their stage, hurrahed by birds,

- goats, brooks. Boys are Lenins,

- Trotskys, little girls are red maids,

- rouged with the blood of cherries,

- ◊

- imitate ramble

- roses, cling in large clusters

- on cemetery

- fences, use the headstones as

- barricades, in mock battles;

- ◊

- serenade the dead,

- on whistling jars, teach parrots

- to mimic the cry

- and the laughter of the mutes:

- hear lovebirds answer thousand

- ◊

- and one riddles which

- the winds ask the graves since the

- coquetting Eve lured

- the handsome serpent in the

- shade of the first apple tree.

- ◊

- Children, aerial

- acrobats, perform feats on

- trapezes, dance on

- ropes with leg flings in Sophic

- rhythms, buck and wing over

- ◊

- roofs like tigermoths,

- announce penny rides to the

- moon, play the snake and

- the snake doctor, eat fire, drink

- venom and piss blood; wistful.

- ◊

- see dusk in, dusk out

- the sun — a fire chariot,

- awaits Elijah,

- to fly him to the heaven

- of Sabbath and wonderfoods.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Burning Village (The Smith & Horizon Press, New York 1972), pp. 85-87.

◊

On God’s Children

- Harry,

- the knife is

- here not even

- to cut the throat of

- a flea. I learned on Pig

- Street that baby pigs are the

- favorite pets of angels that

- knives are here to break bread with all God’s

- children, such as the white little goat who

- promised almonds and raisins in songs of my

- mother when she lulled me to sleep, in the wooden

- cradle, in the wistful village of Mikháleshik.

- ◊

- Harry,

- the knife is

- here only to

- strip nude the fruits from

- the trees of Eden. (I

- heard a weary wanderer

- saying in the shade of a tree:

- all trees are from Eden.) Mine is the

- fire (not the flesh) of the bull—the champion

- lover. Let us drink no toast to life with the

- hunter, Satan’s sportsman, with hands of death. O let

- us not pollue with blood the wine of heaven and earth.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, Two Friends I by Menke Katz & Harry Smith (State of Culture & Horizon Press, New York & London 1981), p. 36.

◊

Snowfall in the Village of Mikháleshik

- Children in my dream

- ful village saw in a snow

- fall the celestial

- hierarchy fall, every

- snowflake—a fallen angel.

- ◊

- Some flakes were seraphs,

- some—cherubs, some archangels.

- Snow brought the crooked

- alleys into heaven. Each

- snowflake left a tear for the

- ◊

- poor synagogue mouse

- and a kiss of peace

- for the dust of the

- nearby cemetery, the

- Eden of my forefathers.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, A Chair for Elijah (Illustrations by Lisa Smith. The Smith, New York 1985), p. 22.

◊

Neverland

- In the

- wind on my

- street, I hear the

- voice of the organ

- grinder, (all that is left

- of him) Yankele Klezmer,

- the alley musician of my

- razed village. I hear the lone, sobbing

- organ barrel ask God, beast, man, Satan:

- which wing, which flying windmill, which distance can

- reach you, my vanished village? Oy Mikháleshik,

- my first love, my last tear, never dying neverland.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, A Chair for Elijah (Illustrations by Lisa Smith. The Smith, New York 1985), p. 23.

◊

Sundown on the Old Street

- Skyborn

- alchemists

- turn the twilight

- slums into goldarn

- castles. Genesis: as

- if God created heaven

- and earth at dusk, here on the old

- street. Adam is a booze hound, drinking

- lechaim to hell. Eve is a lucky

- whore, angels spit pennies from heaven; Eden

- is a bait cherry under her tattered figleaf.

- A pimp—a serpent, dressed to kill, entwines the old street.

- My punky room is a giant’s mirror where I, ages

- hence, live in wonder tales of the village of Mikháleshik.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, A Chair for Elijah (Illustrations by Lisa Smith. The Smith, New York 1985), p. 33.

◊

In the Year of

Three Thousand and One

(on the atomic war)

◊

- The vision of Menke, the son of Heershe-Dovid,

- the poet of potato folk of the village

- of Mikháleshik. I see the end of all

- life on earth, in the year of three thousand

- and one: end of man, bird, king, hangmen.

- The unborn welcome all beyond

- time. Winds will telltale of a

- bygone world. Not an ear

- left to listen. God

- will hide in fear

- of the thug:

- Satan.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, A Chair for Elijah (Illustrations by Lisa Smith. The Smith, New York 1985), p. 44.

◊

Return to the Village of Mikháleshik

◊

- 1.

- When Velfke the mystic returned from every hell on earth, in

- shreds and patches to a heap of burnt ruins which was once

- the singing village of Mikháleshik, he saw like

- Abraham, when thrown into fire, each flame—a rose

- of resurrection. He saw his ancestors:

- proud-blooded beggars slink out of the scorched

- ages, their tears mixed with the ashes

- of Beggar Alley. The aching

- silence outhowled hungry wolves

- in the moonlit fright of

- the forest. Feathers

- of a devoured

- crow haunted

- the wind.

- ◊

- ◊

- 2.

- Velfke the mystic saw God: a guest in heaven as man on earth.

- He saw God dying with the last ray of deathful sunset.

- God was a dead beggar begging life from the dust to which

- all his creations returned. O if Yankele the

- needle-nosed tailor were alive he would sew a

- divine shroud for God but now he must lie shroud-

- less with all the dead in the downed summer,

- in the naked autumn. Gabriel

- flew out of Daniel’s visions,

- embracing with his kind wings

- God’s Edenful being,

- cried Kaddish with the

- first and last life

- on earth: God

is dead. - ◊

- ◊

- 3.

- Velfke the mystic stood like a fablemonger

- listening to a tempest—a thousand roared curse

- against God, terrorizing the storm-lit

- heavens, shouting out time and space: Down

- wretched angels, winged traitors of

- dreams. He heard each thunderbolt

- proclaim he is God’s heir

- to rule the hollow

- heavens, the world

- of each flea

- on earth.

- ◊

- ◊

- 4.

- Velfke the mystic saw Messiah over God’s invisible

- grave eulogize the dead king of life and death: God you drowned in

- your sins. When I, the son of David will come, you will rise

- like all the dead, to atone to every worm, man, beast.

- Only then you may say the light of the first dawn

- is good, only heaven without hell is good,

- only the earth without grief is good. He

- saw Messiah leaving, bound to his

- oath to return at the end of

- night and day. A lost crowd of

- fallen angels like stray

- waifs chummed with dancing

- little bears—the

- playfolk of

- the woods.

- ◊

- From: Menke Katz, A Chair for Elijah (Illustrations by Lisa Smith. The Smith, New York 1985), p. 49.

◊

Deserted Winter House

for the lovers of Mikháleshik: Eltshik & Dveyrke

◊

- The house stands like a

- frozen ice-bound boat. The wind

- shakes the loose beams of

- the mossbushed walls, plays through the

- cold chimney as on a flute.

- ◊

- Stray voices remind

- of yesterfolk. The dying

- day donates the last

- moments of its light to the

- dark stove, blind as its ashes.

- ◊

- A forsaken scythe

- mows time, dreams of ripe-eared corn

- fields, of sated barns.

- A saw aches with broken teeth.

- Death is a next door guest here.

- ◊

- A lucky horseshoe

- on the restless door bangs to

- and fro the dream of

- a dead lover, reborn by

- mother frost on a moonlit

- ◊

- windowpane, gallops

- on a flying horse to meet

- his snowfair love who

- waits for him in an iceboat,

- to sail to bygone ages.

- ◊

- Tempest. The tall oaks

- storm-tossed, leave their wild forest,

- follow the lovers

- in search for their village, lost

- in fire-mouths and high waters.

- ◊

- From Two Friends II by Menke Katz & Harry Smith (Birch Brook Press, Otisville, New York, 1981), pp. 12-13.

◊

Visit to the Village of Mikháleshik

(cinquains)

- ◊

- The wind

- tells desolate

- alleys, there were people:

- laughter, cries here once upon

- a time.

- ◊

- A shot

- rowan tree with

- ailing red pomes, in late

- dusk, stands as in tubercular

- fever.

- ◊

- The last

- bits of bygone

- days hide in cracks of

- walls, live in peace with the prince of

- darkness.

- ◊

- Greenhead

- flies, in a danse

- macabre, mob the swamps.

- Ghouls with eyes like louse-berries feast

- in graves.

- ◊

- Still left

- is Velfke the

- mystic, in sackcloth and

- ashes on his head, mourns the death

- of God.

- ◊

- Malke, the queen of the

- village, in moonlit shrouds,

- joins a stray wolf, barking against

- heaven.

- ◊

- From Two Friends II by Menke Katz & Harry Smith (Birch Brook Press, Otisville, New York, 1981), pp. 66-67.

◊

Dancer

- Yoodl the alley dancer, the jolly beggar

- of the hekdesh — the poorhouse of the village

- of Mikháleshik would for a crust of

- bread: leapfrog, hopscotch through fire, brimstone,

- whirl with the devil-chasers in a

- hellabaloo. In starless

- nights, a winking wick in

- an oilhole repeats each

- dance on the low

- smoke-eaten

- ceiling.

- From: Menke Katz, Nearby Eden (The Smith, New York 1990), p. 16.

◊

Old New York Sundown

- I see my Burning

- Village of Mikháleshik,

- in a sundown of

- old New York. A cloud over

- Cherry Street is like a scorched

- hovel of Beggar Alley.

- From: Menke Katz, Nearby Eden (The Smith, New York 1990), p. 34.

◊

Race of Ghouls

- This

- is not

- a poem.

- It is a curse,

- no bomb can shatter,

- no gas-chamber can choke,

- against all the ghouls — the East

- as the West, the same evil race

- of ghouls, all true lovers of dead Jews.

- No darkness frightens as the cruel daylight,

- on the scorched alleys of my erased village:

- Mikháleshik — dreamland of Lithuania.

- ◊

- Night

- in, night

- out, dream in,

- dream out, I see

- my aunt Beilke in

- moonlit shrouds tell wondrous

- tales. Beyond all beyonds, I

- hear a voice calling: Rise deathless

- Jews from Ponar, Auschwitz, Treblinka,

- like David, father of Messiah, each

- one with a stone in a sling, bring again and

- again the head of a ghoul, in a shepherd’s bag.

- ◊

- From Menke Katz, Nearby Eden (The Smith, New York 1990), p. 96.