O P I N I O N / P I R A M Ó N T / P A P E R T R A I L / O P P O S I T I O N / C E M E T E R I E S

by Milan Chersonski

◊

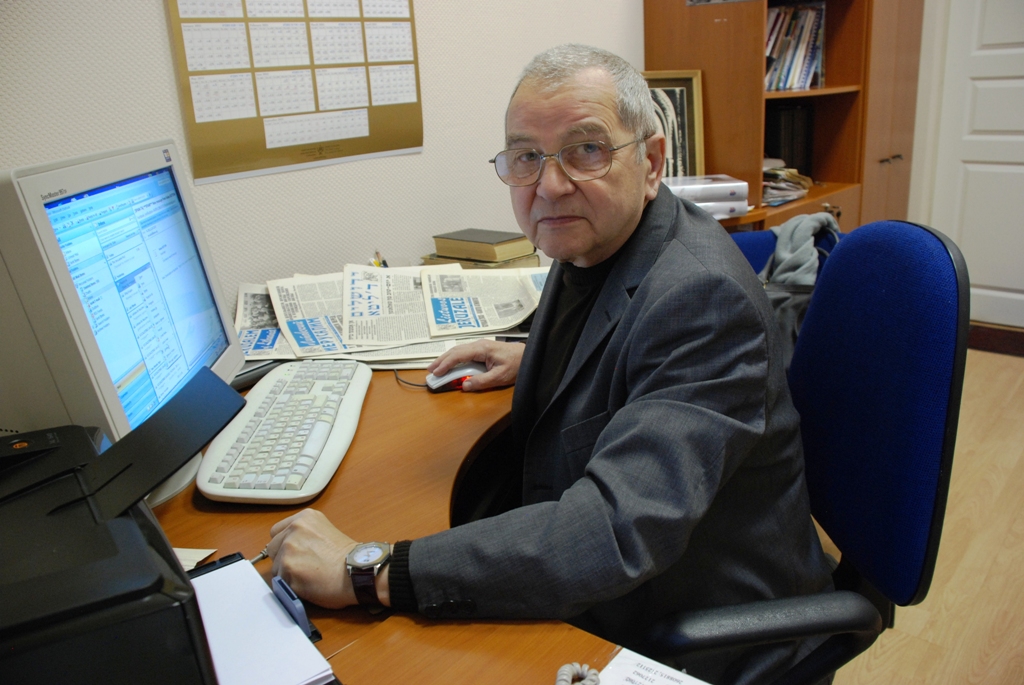

Translated from the Russian by Ludmila Makedonskaya (Grodno); English version approved by the author, Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij), longtime editor (1999-2011) of Jerusalem of Lithuania, quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. He was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania. The views he expresses in Defending History are his own. See also Milan Chersonski section. Photo © Jurgita Kunigiškytė.

Translated from the Russian by Ludmila Makedonskaya (Grodno); English version approved by the author, Milan Chersonski (Chersonskij), longtime editor (1999-2011) of Jerusalem of Lithuania, quadrilingual (English-Lithuanian-Russian-Yiddish) newspaper of the Jewish Community of Lithuania. He was previously (1979-1999) director of the Yiddish Folk Theater of Lithuania. The views he expresses in Defending History are his own. See also Milan Chersonski section. Photo © Jurgita Kunigiškytė.

◊

There were many festive occasions celebrated once Lithuania declared its independence in 1990. So many hopes and expectations were inspired by the sweet word freedom. Free-ee-dom! Laisvė! Had it ever been possible to even imagine beforehand, taking one example, that Lithuania would hold a celebration to honor Israeli Independence Day, dear to Jews all over the world? The new state organized a large event at the Palace of Culture of the Trade Unions in Vilnius in honor of a faraway state, which in Soviet times was mentioned only as “the aggressive state of Israel.”

Here it’s worth recalling a political detective movie that had been made eighteen years before Lithuania’s declaration of independence. Called That Sweet Word Freedom, the film, directed by one of the most talented Lithuanian directors, Vytautas Žalakevičius is set in a Latin American country, and its title called forth so many associations.

Lithuania is not a Latin American country. Lithuania is a European country and one that is deeply entrenched in European history. The independence proclaimed by Lithuania is real independence, and soon all the freedoms existing in European countries would appear in Lithuania.

Alongside all the citizens who defended the right of Lithuania to freedom and independence, were the Jews who stood alongside them on the Baltic Route, hand in hand with their neighbors. In 1989 the delegation of Lithuanian Jewish sportsmen and actors, having been invited to the Maccabiah international games, for the first time in history publicly carried the Lithuanian state tricolor banner at the opening parade.

The decrees of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of Lithuania seemed to be the first signs of the incoming freedom. The Jews of Lithuania were not forgotten during that exciting anticipation of freedom. On 26 April 26 1990, a resolution was adopted with words that Jews in the country had been waiting for over more than four decades:

“The Presidium of the Supreme Council of Lithuania addresses all the Lithuanians and citizens of other nationalities, suggesting that on 29 and 30 April we should remember the historic centuries-long dignified life of Jewish people in Lithuania, clean up and mark their cemeteries, and pay tribute to the memory of the innocent victims buried in the killing fields. Let the blood of innocent victims of all the peoples beat in our hearts, calling out to create a humane and just world.”

The chairman of The Presidium, Vytautas Landsbergis signed the resolution.

Then a meeting of the newly risen Jewish community was held in the Palace of the Trade Unions. Contrary to the custom of celebrating only round-numbered anniversaries, that meeting was devoted to the forty-second anniversary of the independence of Israel. So many people gathered that there were no vacant seats in the 1200 seat hall. Folding chairs had to be brought in. There were not enough of them either. During the entire meeting people stood or leaned up against the walls. A group of the Jews from Israel were sitting in the seats of honor in row no. 9.

Vytautas Landsbergis gave a speech. He read out the statement:

“The Supreme Council of Lithuania declares on behalf of the Lithuanian people that without any exceptions we condemn the genocide of Jewish people during Hitler’s occupation of Lithuania and note with bitterness that Lithuanian citizens were among the executors serving the occupiers.

The crimes committed against the Jewish people in Lithuania and beyond it cannot be justified in any way, nor can there be any statute of limitation for criminal prosecution.

The Supreme Council of Lithuania suggests that all the government bodies, social organizations and citizens should recreate and develop institutions of culture, education, science, religion, etc.

The Lithuanian state will take care of the perpetuation of the memory of the victims of the Jewish victims of genocide. The Republic of Lithuania will not tolerate any manifestation of antisemitism.”

(“Atgimstanti Lietuva ir žydai” in Valstybės žinios, 1997, p. 19. [translated by M.Ch. and L.M.])

That was the way Lithuania celebrated the Jewish state’s national day. The audience stood up and applauded the chairman’s speech for a long time. A lot of those present had tears in their eyes. finally, half a century later, the high note was struck: a moment of truth, a moment of justice.

The spectators, including the Israeli guests, hadn’t paid attention to the long staircase, which they had climbed from Petro Cvirkos street renamed (today’s Pamėnkalnio), though it merited attention. But we’ll come to that later.

◊

T

wenty-five years after that moving event in the Palace of Culture, in the year 2015, a lot has changed. The words declared at the dawn of freedom in 1990 have been erased or just lost their meaning. Even the greatest of optimists no longer believe in them. If anyone today recollects those promises, they will laugh in their thoughts at their own illusions and realize finally that he or she who expects from a promise a lot must wait for three years. Or maybe not.

The events surrounding the historic Jewish Piramónt cemetery in the Šnipiškės district in 2015 now serve as testimony on how one can calmly betray and sell the memory of the Jewish people for twenty-five million dollars, rewrite or even cross out the actual history from seven centuries of life in Lithuania.

Jews had not had their own state for about two millennia, and had survived much misery and untimely loss of many of its dearest people. For them preserving the memory of the past means preserving the identity of Jews as a distinct, unique people wherever they live. Cemeteries in Jewish diasporas played the role of eternal memory books of their ancestors and their history. It was the same in Lithuania. The earthly remains buried below and the gravestones and texts engraved on them above are the pages and chapters of Jewish history. Preservation of the memory about ancestors via their cemeteries is, on the one hand, a sacred Jewish responsibility to those ancestors and, on the other hand, a duty to their children and future generations.

Nazi Germany, having occupied Lithuania in 1941, didn’t care about the Jewish cemeteries. It concentrated on its prime objective, the Final Solution of the Jewish question, the total annihilation of the Jewish people.

The headquarters of the Lithuanian Activist Front (LAF) was founded in Berlin while the Germans were organizing an uprising against the Soviet state. In its propaganda leaflets it widely opened the gates to the destruction of Lithuanian Jewry, hence also to the destruction of Jewish cemeteries. The leaflets directed the way to the Nazi notion of “social justice.” Here is the text of one of the leaflets named “Let’s Liberate Lithuania from the Jewish Yoke Forever” (Amžiams išvaduokim Lietuvą iš žydijos jungo), which was composed in Berlin headquarters of LAF under Kazys Škirpa’s leadership. The leaflet proclaims outright:

“All the movable and immovable assets in possession of Lithuanian Jews, which were acquired through swindle and exploitation of Lithuanians, the fruits of their labor and sweat, will pass into the ownership of Lithuanian people. This property is equitably granted in the first instance to Lithuanians, the most active fighters for liberation of Lithuania from the Bolshevik and Jewish oppression. Any noticed attempt by the Jews to destroy or damage the property will immediately be punished.” [emphasis added — M. Ch.]

During the Nazi occupation local hunters for jewelry, confident that they would find diamonds, gold and the like in Jewish graves began to ravage Jewish cemeteries. They overturned headstones, excavated and actually searched the human remains. Centuries-old gravestones at Jewish cemeteries, having lost their natural guardians the descendants and relatives of the buried, turned into a free-of-charge, unguarded source of building materials for cowsheds, pigsties, poultry houses and other outbuildings, which belonged to some members of the indigenous population.

◊

The practice of destroying old cemeteries, regardless of their national and religious affiliation, was widespread in the USSR. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, Stalin’s attitude towards cemeteries spread through Lithuania. But the local situation was taken into account. Looting of Christian cemeteries could cause unwanted conflicts between the Communist government of the republic and the local population. But the few remaining Jews would keep silence: they were shocked by what had descended on their people. During the Nazi occupation more than 95% of the Jewish residents of Lithuania were killed. The Jews, who survived the horrors of ghetto and concentration camps, feared everyone and everything. During the war, they saw death every day and sometimes every hour, and were on more than one occasion themselves prepared to accept it. Those lucky enough to come back from the concentration camps or evacuation or hiding, on their return to Lithuania were afraid of reprisals even for the fact that they survived. Some saw mountains of corpses at Auschwitz-Birkenau and other death camps. They feared everyone and everything even after returning to their homeland. Therefore, the issue of Jewish cemeteries in Lithuania had its special green-light history.

It is important to note that only Jewish cemeteries were devastated. Catholic, Orthodox, Tatar and Karaimic cemeteries were usually not touched.

The events connected with the monument to the Jews killed at Ponár, in the Paneriai forest, can serve as a typical example of the attitude of the Soviet authorities toward the Jews. It is well known that from 1941 to 1943 local Nazi collaborators under German officers’ command killed about one hundred thousand people at Ponár, more than seventy thousand of whom were Jews from Vilnius and surrounding areas. About thirty thousand people were Soviet prisoners of war. Later the hundred thousand or so bodies were burned and the ashes scattered all over the forest.

After World War II, the Jews of Vilnius with their own money erected a monument to the murdered Jews at Ponár. The text engraved on the monument stated that seventy thousand Lithuanian Jews had been killed. Moreover, those words were carved in granite in Hebrew, a secretly banned language in the USSR.

Rumors about the monument financed by survivors reached the Central Committee of the Communist party of Lithuania. The Minister for State Security of the Lithuanian SSR came to Paneriai to examine the situation. Having scrutinized the “object,” he reported to the Central Committee’s First Secretary, Antanas Sniečkus that the monument “had been made in religious style” and “did not feature anything Soviet.” In 1952 Soviet law enforcement blew up the monument. Some thirty meters from where it had stood, a standard Soviet stele was put up. The inscription on it said, “Here are buried Soviet people who were exterminated by the German fascist invaders.” All over Lithuania, at more than two hundred sites of mass extermination of Jews, memorial signs to “Soviet people” were put up, and the murderers were called “German fascist invaders.” There was no mention anywhere that Jews had been shot mostly by Nazi collaborators from the local population.

◊

In the second half of the 1950s, after Stalin’s death, the Soviet program of active urban development started up in Lithuania. Lithuania suffered from an acute shortage of building materials. Systematic pilfering of tombstones from the old burial grounds in Šnipiškės (the Piramónt Jewish cemetery) and Užupis (the Zarétshe Jewish cemetery) helped in some measure to overcome the shortfall. Soviet authorities organized mechanized conversion of Jewish tombstones into building materials for administrative offices, new theaters and cinemas, school buildings, palaces of culture, newly laid roads, street sidewalks, retaining walls and more.

And that happened despite the fact that many prominent Jewish personalities, who have places of permanent pride in Jewish and wider history and culture, were buried at those cemeteries. The earth, which contained the remains of tens of thousands of Jews, was leveled with bulldozers, and a sports palace (Sporto rumai) was constructed on a section of the old Piramónt cemetery in Šnipiškės.

In a 2002 article called “Is Užupis Jewish Cemetery Destined to Disappear?” (first published in the Lithuanian language daily Lietuvos rytas), Joseph Levinson (1917-2014), a prominent leader of the post-Soviet Lithuanian Jewish community wrote:

“Tombstones are Love and Sorrow fastened with tears. Man continues man in the memory of his heart, in the continuation of his deeds. It is a sacred symbol that connects earthly life with the endless universe.”

Here is one example of how widely builders used gravestones from Jewish cemeteries during the postwar years. The Palace of Trade Unions of the Lithuanian Republic of the USSR, mentioned near the beginning of this article, was built on the top of Tauro Hill, one of the highest points in Vilnius. Two 170 and 175 step stairways led to that building from Petro Cvirkos Street (renamed Pamėnkalnio). Each of the stairways was four meters wide. But nobody recorded how many granite gravestones from Jewish cemeteries were destroyed to build up those two sadly notorious outdoor sets of stairs. After rainwater accumulations, it often became possible to make out the contours of Jewish letters.

There are likely a lot of Jewish gravestones in the basement of the Palace of Trade Unions too. It is not improbable that during the construction of the large funeral home in the area of the former Jewish cemetery in Užupis (Zarétshe), granite and marble slabs from the ravaged historic Jewish cemetery, located in that area, were also used. In some Lithuanian cities one can still see granite and marble of Jewish tombstones.

After the restoration of Lithuania’s independence, at the request of local and particularly foreign Jews, visiting Lithuania from Israel and the United States, the cemetery steps to the Palace of Culture of the Trade Unions were replaced by granite blocks purchased abroad.

From the steps, that had been spared, at the request of the Jewish Community of Lithuania, architect Jaunius Makariūnas fashioned a monument To the Destroyed Jewish Cemeteries. The monument is located in Olandų street on the way to the funeral home.

In 1993 a memorial sign, by the same architect, was put up in the Piramónt cemetery in Šnipiškės. This sign is located not far from the sports palace. A series of photos of the destruction of Jewish cemeteries was made by then young and now prominent Lithuanian photographer Rimantas Dichavičius. The Jewish State Museum in Vilnius sadly did not bother to open a permanent exhibition of those stunning photographs.

◊

Three Vilnius plots of land areas were purchased in different centuries from the city administration for burying deceased Jews. Land in Vilnius has always been very expensive. And Jews always paid more for it than any other national minority. The only way to collect the necessary sum was an extra tax on all Jewish families. Over the centuries, the Jewish community bought land for three cemeteries in the areas known as Šnipiškės, Užupis, and Sudervės. The third, dating just before the war, remains open to this day, but in Soviet times part of its land was given away to other communities’ confessions for unknown reasons.

◊

How do these plots of land relate to the people who have today assigned to themselves the right to take charge of legitimately purchased property, and in violation of all norms of human ethics put a stranglehold on a twenty-five million dollar project for renovation or transformation of the old Sports Palace, which is built on the bones of Vilna’s Jews? In other words, certain parties will receive money for the transformation of the building illegally built in Soviet times on the cemetery, which had been bought by the Lithuanian Jewish community centuries earlier?

After the restoration of Lithuania’s independence new laws were adopted. But nobody ever abrogated the purchase or sale of the land of the city’s three Jewish cemeteries. If the current state of Lithuania is the historical successor to that which existed before World War II, the historic act of purchase and sale must be considered legitimate and binding. Neither during the Nazi occupation, nor under the Soviet regime were the historic contracts between the Vilnius Jewish community and local municipality nullified. Both Hitler’s Germany and the Soviet Union abused laws. The pilfering of land and stones and bones at Užupis and Šnipiškės were thoroughly illegal.

Surely, after restoration of her independence, Lithuania would now wish to act with respect for her own historical laws return those troubled plots of urban land to their rightful owners just as she would return to peasants and farmers Lithuanian land pilfered during the period of Soviet collectivization. And indeed: the illegally expropriated from the citizens of Lithuania property was returned to them. As for the Jews, nobody found it necessary to return the illegally taken away property to them. The return of Jewish property is still a sore subject.

◊

H

ow could it happen that today’s democratic Lithuanian government continues the same policy of destroying Jewish cemeteries as the Soviet government? Someone or other may argue that today on the territory of the Šnipiškės cemetery there are no human remains at the two-meter depth. Who and how made it possible to proclaim such Judenfrei status for the oldest Jewish cemetery in the city?

There are, incidentally, no convincing arguments that this is true. But even if that were the bitterest truth, would even that give anyone the right to use the territory related to the historical tragedy of Lithuanian Jews for the construction and now transformation of the Soviet sports palace?! Or are there people who are dead-set on a new national congress center coming into existence precisely on the historic Jewish cemetery?

How can the plans to use the former cemetery be understood after Vytautas Landsbergis’ promise, given to the participants of the meeting dedicated to the forty-second anniversary of the State of Israel in 1990: “The Lithuanian state will take care of perpetuation of the memory of the genocide victims of Jewish people. The Republic of Lithuania will not tolerate any demonstration of antisemitism.”

For whom is it not clear that the transformation of the sports palace, which stands on the cemetery, is a direct desecration of history and the traditions of Lithuanian Jewish heritage?

Unfortunately, neither the Lithuanian authorities, nor the current leadership of the Jewish Community of Lithuania earnestly want to yield to reason, to take into account the protests of Jews worldwide on the transformation of the old sports arena into a new congress center right in the middle of the cemetery. It seems that twenty-five million dollars allegedly for restoration of the sports palace on Jewish bones is more important than morality. In that case are the recipients of those millions any better than the Bolsheviks?

◊

PS It is said that Jews like to talk a lot. But after World War II Lithuanian Jews became the most silent minority in Lithuania. Demography is the most compelling feature of Jews’ relationship to current events. The first postwar census was held in Lithuania in 1959. It counted 24,658 Jews in the Lithuanian SSR. In 2011, the census counted 3,050 Jews. In silence, with tears in their eyes, Jews are leaving Lithuania.